Kosagaigarh

| Author: Laxman Burdak IFS (R) |

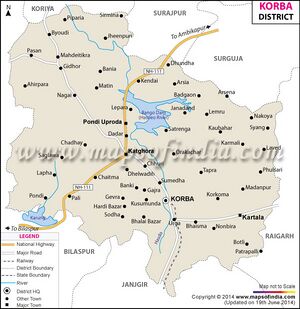

Kosagaigarh (कोसगईगढ़) is a site of an ancient fort in Korba district, Chhattisgarh, situated 25 kms off Korba-Katghora Road on the hillocks of Putka Pahad.

Variants

- Kosgai (कोसगई)

- Kosgain (कोसगई)

- Kosagaigarh (कोसगईगढ़)

- Kosanga (कोसंग)

Location

Origin

History

Kosgain Stone Inscription (No.I) of Vahara was originally found in the fort of Kosgain, 4 miles to the north-east of Chhuri, the chief town of the former Chhuri Zamindarî in the Korba district of Chhattisgarh. The inscription is one of the king Vahara who belonged to the Haihaya i e, Kalachuri Dynasty of Ratanpur. The object of it seems to be to record the king's victory over some Pathans. The inscription is not dated, but from the other inscription on the same stone, which belongs to the same reign and is dated in the Vikrama year 1570, as well as from the Ratanpur Stone Inscriptions Of Vahara: (Vikrama) Year 1552 (=1495 AD), which mentions the artisans Chhïtaku and Mandana, it is clear that Vâharèndra flourished at the end of the fifteenth and in the beginning of the sixteenth century A C.[1]

Kosagaigarh

Kosagaigarh fort was built by Raja. Natural walls protect it and so only at some parts the builders felt the need of constructing walls. From this place, which is situated 1570 feet from the sea level, a big part of Korba district is visible.

At the main entry point of the fort there is a tunnel like passage, where there is space for only one person can walk.

During war the soldiers of the king used to prevent the enemy by rolling down big stones from the fort.

Remains of ancient structures like etc. are scattered around the hill. The fort is hidden in the dense forest, which is the home for wild animals like beer, leopard etc.

Source - https://korba.gov.in/en/tourist-place/kosagaigarh/

Kosgain Stone Inscription (No. I) of Vahara

This inscription was first brought to notice by Mr. Beglar in Sir A Cunningham's Archœological Survey of India Reports, Vol VII, p 214. It was subsequently noticed very briefly in Mr. Nelson's Bilaspur District Gazetteer, P 37 and later on in RB. Hiralal's Inscriptions in the Central Provinces and Berar.1. It is edited hère for the first time from the original stone which is preserved in the Central Museum, Nagpur.

The inscription is engraved on one side of a slab of reddish sand-stone which was originally found in the fort of Kosgain,2 4 miles to the north-east of Chhuri, the chief town of the former Chhuri Zamindarî in the Bilaspur District of Madhya Pradesh. The same stone contains another record, incised on the other side, which also belongs to the reign of Vâhara 3

1. First ed, pp. 1 14-15, second ed , p 126

2. The fort of Kosgain is described in detail by Beglar in Cunningham's A S.I R., Vol XIII, p.153ff.

3. No 106, below.

[p.558]: The present inscription, which contains twenty lines....The characters are Nâgarï and the language, Sanskrit. Except for siddhi-sri-Ganêshàya namah in the beginning and the names of sculptors at the end, the whole record is metrically composed. The verses, all of which are numbered, total 23. The orthography does not call for any remark except that b is everywhere denoted by the sign for v.

The inscription is one of the king Vahara who belonged to the Haihaya (i e, Kalachuri) Dynasty of Ratanpur. The object of it seems to be to record the king's victory over some Pathânas.

After the customary obeisance to Ganesa, the record opens with three invocatory verses in honour of Lambodara (Ganesa), Siva and Durgà. It then describes the Moon, the mythical progenitor of the Haihaya (or Kalachuri) family.

The first historical prince, named after the legendary kings Haihaya1 and Kârtavirya, is Singhana (सिंघण) (V.6). The name of his son, which is partly damaged, seems to have been Danghira (डांघीर) (V.6). His son was Madanabrahman (मदनब्रह्मा) (V.6), from whom was born Râmchandra (रामचंद्र) (V.6). The latter's son was Ratnasena (रत्नसेन) (V.7),2 whose son, apparently from his wife Gundayi (गुण्डायी) (V.7), was Vaharemdra (वाहरेन्द्र) (V.8).

We are next told that when Vâharèndra marched with his army, the Pathânas used to run away in apprehension to the river Sona (सोण), while others, giving up their kingdoms, wealth and life, took shelter in the fortress of heaven. From Ratnapura, the king used to bring to his capital wild elephants and give them away together with gold to his suppliants. He used to make gifts of cows and burn a hundred thousand lights in honour of the goddess Durgà3 in the month of Kârttika. He stored abundant wealth and provisions in the fortress of Kosanga (कोसंग), from which he used to sally forth in search of enemies

The inscription next describes, in verses 16-17, the king's councillor Mâdhava, who defeated certain enemies whose names are illegible, and wrested away their fortue. He is also said to have vanquished the Pathânas and annexed their territory, carrying away a large booty of gold and other (precious) metals, horses and elephants, as well as cows and buffaloes.

Vâharèndra's family-priest was Dêvadatta Tripâthï, who used to advise him rightly in accordance with the sâstras and the science of politics. We are next told that the king once gave a huge elephant to a learned man named Nàganâtha, who had hailed from Karnata, for composing the prasasti of Durgâ. The present record, which is also called a prasasti of Durga was composed by Nàganâtha and written by Râmadâsa the son of Môhana. Next is mentioned a Kayastha named Jagannâtha, a trusted servant of Vâharèndra. Finally, the record states that the artisan (Sutradhàra) Manmatha, had two sons Chhitaku and Mândana, of whom the latter incised the present prasasti.

1. Hiralal's statement that 'the genealogy traces the origin in a somewhat novel manner to a family in which king Haya was born, after whom some other names are mentioned which are illegible until one comes to Kârtavîryârjuna' is evidently due to misreading Haihaya, not Haya, is mentioned in v 5 and he was directly followed by Kârtavïrya Arjuna.

2. Hiralal's statement that Harishchandra was another son of Râmachandra is evidently wrong. Harishchandra, who is mentioned in the beginning of verse 8 in connection with the description of Vâharèndra, was a legendary king noted for his liberality.

3. Beglar has described the shrine of Pârvatî (now called Kosgain Mâtâ) which is situated on the summit of a sharply pointed peak called Kosgain-garh. See Cunningham's A S I R Vol XIII, p 155.

[p.559]: The insctiption is not dated,1 but from the other inscription on the same stone, 2 which belongs to the same reign and is dated in the Vikrama year 1570, as well as from the Ratanpur inscription3 dated in the Vikrama year 1552, which mentions the artisans Chhïtaku and Mandana, it is cleat that Vâharèndra flourished at the end of the fifteenth and in the beginning of the sixteenth century A C

There are only two places mentioned in the present record Of them,

Ratnapura, already identified, was for a long time the capital of the Kalachuris in Chhattisgarh, though at the time of the present prasasti the seat of the government seems to have been shifted to the fort of

Kosgain in the hilly tract to the north-east, probably on account of Muslim invasions Kôsanga is evidently the fort of Kosgain in the former Chhuri Zammdari, where the inscribed stone was originally discovered 4

1. According to Hiralal, the inscription was dated, but has broken off exactly where the year was given. This does not appear to be correct. The date, if the inscription contained one, should have come at the end as in No 106 below, and there the record is fairly well preserved

2. Below, No 106.

3. Above, No 104

4. Mr Beglar's supposition that the stone was brought from elsewhere, because it is inscribed on both the sides (C A S I R, Vol XIII, p 157) is thus untenable

Wiki editor Notes

- Chhitar (Jat clan) = Chhitaku (छीतकु). Chhitaku is mentioned as son of Manmatha, the Sutradhara of Kosgain Stone Inscription (No.I) of Vahara. [2]

- Danghar (Jat clan) = Danghira (डांघीर) was ancestor of King Vaharemdra (वाहरेन्द्र) mentioned in Kosgain Stone Inscription (No.I) of Vahara. [3]

- Hayal (Jat clan) = Haya . Kosgain Stone Inscription (No.I) of Vahara mentions King Haya in fn-1... The inscription is one of the king Vahara who belonged to the Haya/Haihaya Dynasty. [4]

- Korwa (Jat clan) = Korba. Korba is a town and district in Chhattisgarh.

- Lamboria (Jat clan) = Lambodara (लम्बोदर). Lambodara is mentioned in verse-1 of Kosgain Stone Inscription (No.I) of Vahara. The record opens with three invocatory verses in honour of Lambodara (Ganesa), Siva and Durgà. It then describes the Moon, the mythical progenitor of the Haihaya (or Kalachuri) family. [5]

- Madan (Jat clan) = Madanabrahman (मदनब्रह्मा) was ancestor of King Vaharemdra (वाहरेन्द्र) mentioned in Kosgain Stone Inscription (No.I) of Vahara. [6]

- Mandan (Jat clan) = Mandana (मांडण). Mandana is mentioned as son of Manmatha, the Sutradhara of Kosgain Stone Inscription (No.I) of Vahara. [7]

- Sepat (Jat clan) = Sepat is a village in Podi-Uproda tahail of Korba district in Chhattisgarh.

- Singhana (Jat clan) = Singhana (सिंघण) was ancestor of King Vaharemdra (वाहरेन्द्र) mentioned in Kosgain Stone Inscription (No.I) of Vahara. [8]

- Vahar (Jat clan) = Vahara (वाहर) also called Vaharendra (वाहरेन्द्र) is mentioned in Kosgain Stone Inscription (No.I) of Vahara. The inscription is one of the king Vahara who belonged to the Haihaya i e, Kalachuri Dynasty of Ratanpur. The object of it seems to be to record the king's victory over some Pathânas. [9]

Kosgain Stone Inscription (No.II) Of Vahara: (Vikrama) Year 1570 (=1513 AD)

[p.563]: This inscription, together with another3 on the same stone, was first brought to notice by Mr. Beglar in Sir A Cunningham's Archaeological Suvey of India Reports, Vol VII, p. 214. It was subsequently very briefly noticed by Rai Bahadui Hiialal in his Inscriptions in the Central Provinces and Berar4 It is edited here from the original stone, now deposited in the Central Museum, Nagpur.

The record is engraved on the opposite side of the same slab of reddish sand-stone which bears the preceding inscription of Vahara. As stated before, the stone was originally found in the fort of Kosgain, 4 miles north-east of Chhuri in the Bilaspur District of Madhya Pradesh.

The inscription contains fifteen lines....The characters are Nâgari, the average size of the letters being 5". The language is Sanskrit.....

3. No 105, above.

4. First ed , pp 114 ff, second éd., p 126,

[p.564]: The inscription, called prasasti in line 11, is one of Ghâtama (घाटम),1 (L.10) a feudatory of the Kalachuri prince Vâhara. The object of it is apparently to commemorate the death, in battle, of Yasha, the father-in-law of Ghatama. The record was composed by the poet Chandrâkara and written on the stone by Mândêka (मांडेक) (L.11,V.15). It was engraved by Vira, the son of Kôsura (कोसुर) (L.15).

After the customary obeisance to Mahâ-Ganêsha, the inscription opens with three verses in honour of Ganesha, Ambika and Murari (Krishna). We are next told that in the Lundela (लुण्डेल) (L.3) family was born Karnadeva (कर्णदेव) (L.4). His son Yasha (L.4) gave his daughter in marriage to Ghâtama. After consigning his son Sauridasa (सौरीदास) (L.5) to Ghâtama's care and putting him in possession of his territory and treasure, Yasha attacked some enemies2 whose names are not mentioned. The record next mentions Tejanarayana (तेजनारायण) (L.6) who is said to have lost his life on the battlefield.

With verse 9 begins the genealogy of Ghatama (घाटम). In the Châyuhâna (Chauhan) (L.7) family there was a prince named Nirdevala (निर्देवल) (L.7). His son was Bharata (L.8). After him is mentioned Ghâtama who, though it is not expressly stated, was probably his son and successor. Ghâtama (घाटम) (L.9) obtained possession of a heaven-like fortress (evidently Kosanga (कोसंग) , modern Kosgain) and was greatly favoured by the king Vahara. His minister was Goraksha (गोरक्ष) (L.10), who had apparently a son named Vaijala (वैजल) (L.11). Verse 18 states that Ghâtama gave cows, yielding good milk and decked with gold and cloth, together with their calves to the poet Chandrâkara who composed this prasasti by his order.

The inscription is dated,3 in lime 14, in the year 1570, the cyclic year being Vikrama, on Monday, the thirteenth tithi of the dark fortnight of Âshvina.4 This date must evidently be referred to the Vikrama era. In the northern Vikrama year 1570 expired, the thirteenth tithi of the dark fortnight of the pûrnîmànta Ashvina commenced 2 h. 50 m after mean sunrise on Monday The cyclic year was Vikrama according to the northern lunar-solar System 5 Though the tithi was not civilly connected with Monday, it must have been so cited because it was current when the inscription was put up. The corresponding Christian date is the 26th September 1513 A.C.

1. His aame appears as Ghàtamma in verses 7, 14 and 17-19 owing to the exigencies of the mètre.

2. They were perhaps the Pathânas whom Vâhara claims to have vanquished in L.8 of No. 105, above

3. Hiralal's statement that the inscription has broken off where the year was given is not correct. The figures of the year, though somewhat indistinct, can be read without much difficulty on the original stone.

4. There is another date in L.13, viz , Wednesday, the 10th tithi of the bright fortnight in the first or intercalary Mâgha .There was, however, no intercalary Mâgha in or about the Vikrama year 1570.

5. According to the southern lunar-solar System, it was shrïmukha.

Wiki editor Notes

- Bajolia (Jat clan) = Vaijala (वैजल). Vaijala was son of Goraksha, Minister of King Vahara of Kosagaigarh, mentioned in (L.10) of Kosgain Stone Inscription (No.II) Of Vahara - (Vikrama) Year 1570 (=1513 AD). Kosgai or Kosagaigarh is a village Korba district, Chhattisgarh, situated 25 kms off Korba-Katghora Road on the hillocks of Putka Pahad.[10]

- Ghat (Jat clan) = Ghatama (घाटम). Ghatama (घाटम) was a feudatory of the Kalachuri prince Vahara mentioned in (L.10) of Kosgain Stone Inscription (No.II) Of Vahara: (Vikrama) Year 1570 (=1513 AD). The stone was originally found in the fort of Kosgain, 4 miles north-east of Chhuri in the Bilaspur District of Chhattisgarh. With verse 9 begins the genealogy of Ghatama (घाटम). In the Châyuhâna (Chauhan) (L.7) family there was a prince named Nirdevala (निर्देवल) (L.7). His son was Bharata (L.8). After him is mentioned Ghâtama who, though it is not expressly stated, was probably his son and successor. Ghâtama (घाटम) (L.9) obtained possession of a heaven-like fortress (evidently Kosanga (कोसंग) , modern Kosgain) and was greatly favoured by the king Vahara. His minister was Goraksha (गोरक्ष) (L.10), who had apparently a son named Vaijala (वैजल) (L.11). Verse 18 states that Ghâtama gave cows, yielding good milk and decked with gold and cloth, together with their calves to the poet Chandrâkara who composed this prasasti by his order. (p.564) [11]

- Gorakshak (Jat clan) = Goraksha (गोरक्ष). Goraksha was minister of Ghatama (घाटम), who was a Chauhan vansha feudatory King of the Kalachuri prince Vahara and possessed heavenly fort Kosagaigarh. Goraksha (गोरक्ष) is mentioned in (L.10) of Kosgain Stone Inscription (No.II) Of Vahara - (Vikrama) Year 1570 (=1513 AD). Kosgai or Kosagaigarh is a village Korba district, Chhattisgarh, situated 25 kms off Korba-Katghora Road on the hillocks of Putka Pahad.[12]

- Kosar (Jat clan) = Kosura (कोसुर). Kôsura (कोसुर) (L.15) is mentioned in Kosgain Stone Inscription (No.II) Of Vahara - (Vikrama) Year 1570 (=1513 AD). It was engraved by Vira, the son of Kôsura (कोसुर) (L.15). (p.564).[13]

- Lunda (Jat clan) = Lundela. Lundela (लुण्डेल) (L.3) family is mentioned in Kosgain Stone Inscription (No.II) Of Vahara - (Vikrama) Year 1570 (=1513 AD) in which was born Karnadeva (कर्णदेव) (L.4). Kosgai or Kosagaigarh is a village Korba district, Chhattisgarh, situated 25 kms off Korba-Katghora Road on the hillocks of Putka Pahad.[14]

- Mandak (Jat clan) = Mandeka. Mândêka (मांडेक) (L.11,V.15) was the writer of Kosgain Stone Inscription (No.II) Of Vahara - (Vikrama) Year 1570 (=1513 AD). The stone was originally found in the fort of Kosgain, 4 miles north-east of Chhuri in the Korba District of Chhattisgarh. [15]

- Vahar (Jat clan) = Vahara (वाहर) also called Vaharendra (वाहरेन्द्र) is mentioned in Kosgain Stone Inscription (No.II) Of Vahara: (Vikrama) Year 1570 (=1513 AD). [16]

Gallery

External links

References

- ↑ Corpus Inscriptionium Indicarium Vol IV Part 2 Inscriptions of the Kalachuri-Chedi Era, Vasudev Vishnu Mirashi, 1905, p.557-563

- ↑ Corpus Inscriptionium Indicarium Vol IV Part 2 Inscriptions of the Kalachuri-Chedi Era, Vasudev Vishnu Mirashi, 1905, p.557-563

- ↑ Corpus Inscriptionium Indicarium Vol IV Part 2 Inscriptions of the Kalachuri-Chedi Era, Vasudev Vishnu Mirashi, 1905, p.557-563

- ↑ Corpus Inscriptionium Indicarium Vol IV Part 2 Inscriptions of the Kalachuri-Chedi Era, Vasudev Vishnu Mirashi, 1905, p.557-563

- ↑ Corpus Inscriptionium Indicarium Vol IV Part 2 Inscriptions of the Kalachuri-Chedi Era, Vasudev Vishnu Mirashi, 1905, p.557-563

- ↑ Corpus Inscriptionium Indicarium Vol IV Part 2 Inscriptions of the Kalachuri-Chedi Era, Vasudev Vishnu Mirashi, 1905, p.557-563

- ↑ Corpus Inscriptionium Indicarium Vol IV Part 2 Inscriptions of the Kalachuri-Chedi Era, Vasudev Vishnu Mirashi, 1905, p.557-563

- ↑ Corpus Inscriptionium Indicarium Vol IV Part 2 Inscriptions of the Kalachuri-Chedi Era, Vasudev Vishnu Mirashi, 1905, p.557-563

- ↑ Corpus Inscriptionium Indicarium Vol IV Part 2 Inscriptions of the Kalachuri-Chedi Era, Vasudev Vishnu Mirashi, 1905, p.557-563

- ↑ Corpus Inscriptionium Indicarium Vol IV Part 2 Inscriptions of the Kalachuri-Chedi Era, Vasudev Vishnu Mirashi, 1905, p.563-568

- ↑ Corpus Inscriptionium Indicarium Vol IV Part 2 Inscriptions of the Kalachuri-Chedi Era, Vasudev Vishnu Mirashi, 1905, p.563-568

- ↑ Corpus Inscriptionium Indicarium Vol IV Part 2 Inscriptions of the Kalachuri-Chedi Era, Vasudev Vishnu Mirashi, 1905, p.563-568

- ↑ Corpus Inscriptionium Indicarium Vol IV Part 2 Inscriptions of the Kalachuri-Chedi Era, Vasudev Vishnu Mirashi, 1905, p.563-568

- ↑ Corpus Inscriptionium Indicarium Vol IV Part 2 Inscriptions of the Kalachuri-Chedi Era, Vasudev Vishnu Mirashi, 1905, p.563-568

- ↑ Corpus Inscriptionium Indicarium Vol IV Part 2 Inscriptions of the Kalachuri-Chedi Era, Vasudev Vishnu Mirashi, 1905, p.563-568

- ↑ Corpus Inscriptionium Indicarium Vol IV Part 2 Inscriptions of the Kalachuri-Chedi Era, Vasudev Vishnu Mirashi, 1905, p.563-568

Back to Chhattisgarh