Tyana

| Author:Laxman Burdak, IFS (R) |

Tyana was an ancient city in the Anatolian region of Cappadocia, in modern Kemerhisar, Niğde Province, Central Anatolia, Turkey. It was the capital of a Luwian-speaking Neo-Hittite kingdom in the 1st millennium BC.

Variants

- Tyana (Pliny.vi.3)

- Ancient Greek: Τύανα

- Tuwana (Hieroglyphic Luwian)

- Tuḫana (Akkadian)

- Tuwanuwa (Hittite)

- Thoana

Jat Clans

Jat Gotras Namesake

- Tiwana = Tyana (Pliny.vi.3)

Location

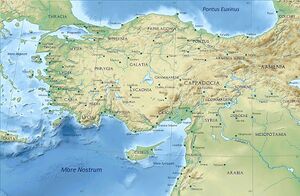

The location of Tyana corresponds to the modern-day town of Kemerhisar in Niğde Province, Turkey. The region around Tyana was known as Tyanitis, and it corresponded to roughly the same area as the former Iron Age kingdom of Tuwana, which extended to the Cilician Gates and the kingdom of Quwê in the south, and in the north was bordered by the region of Tabal, which is sometimes considered part of Tuwana.

Name

The name of the city and the region, and later kingdom, surrounding it was Tuwana in the Hittite and Neo-Hittite periods. By the Hellenistic and Roman periods, the city was named Tyana, which was derived from its earlier Hittite name.

History

Hittite period: Tyana is the city referred to in Hittite archives as Tuwanuwa. During the Hittite Empire period in mid 2nd millennium, Tuwanuwa was among the principal settlements of the region along with Hupisna, Landa, Sahasara, Huwassana and Kuniyawanni.[1] This south-central Anatolian region was referred to as the Lower Land in Hittite sources and its population was mainly Luwian speakers.[2]

Neo-Hittite period: Following the collapse of the Hittite Empire, the city of Tuwana became the centre the Iron Age Luwian kingdom of Tuwana in southern Anatolia, one of the Syro-Hittite states, which existed in southeastern Anatolia in the 8th century BC.

It is not certain whether or not it was initially subject to the Tabal kingdom to its north, but certainly by the late 8th century BC it was an independent kingdom under a ruler named Warpalawa (in Assyrian sources Urballa).[3] He figures in several hieroglyphic Luwian inscriptions found in the region, including a monumental rock carving in Ivriz.[4] Warpalawa is also mentioned in Assyrian texts, under the name Urballa, first in a list of tributees of Assyrian king Tiglath Pileser III and later in a letter of Sargon II.[5] Warpalawa was probably succeeded by his son Muwaharani whose name appears in another monument found in Niğde.[6]

At this time, Tabal and Tuwana were tributaries of the Assyrian Empire of Tiglath-Pileser III. Simultaneously, strong influence from the kingdom of Mushki, ruled by King Mita (who is often identified with Midas of Phrygia, known from Greek sources) is evident. The Phrygian evidence is seen in two Old Phrygian inscriptions, which were found in Kemrhisar, and by bronze objects of clear Phrygian origin in a tumulus at Kaynarca, seven kilometres northeast of Tyana. In a letter of 715 BC, Sargon II describes how King Mita of Mushki had sent emissaries to the Assyrian governor in Quwê, Ašur-Šarru-Usur, asking for an exchange of ambassadors. The accompanying ambassadors of Warpalawas II (Akkadian: Urballa) are there described as messengers of one of Mita's vassals. A report of Ašur-Šarru-Usur to Sargon II indicates that Warpalawas conquered Bit Burutaš (part of Tabal) in 713 BC after King Ambaris of Tabal had been deposed and deported to Assyria. İvriz relief a stele of Tarḫunz with a Luwian-Phoenician bilingual text, which was found in 1986, shows that the North-Syrian Aramaic cultural area had a strong influence on the area as well. The Niğde Stele, which was erected by Warapalawas’ son, Muwaharani II, is clearly modelled on Assyrian steles. In the subsequent period, when both the Phrygian kingdom and the kingdom of Urartu to the east fell to the Cimmerians, there are no further traces of Tuwana.

Greek and Roman periods: In Greek legend, the city was first called Thoana because Thoas, a Thracian king, was its founder (Arrian, Periplus Ponti Euxini, vi); it was in Cappadocia, at the foot of the Taurus Mountains and near the Cilician Gates (Strabo, XII, 537; XIII, 587).

Xenophon mentions it in his book Anabasis, under the name of Dana, as a large and prosperous city. The surrounding plain was known after it as Tyanitis.

It is the reputed birthplace of the celebrated philosopher (and reputed saint or magician) Apollonius of Tyana in the first century AD. Ovid (Metamorphoses VIII) places the tale of Baucis and Philemon in the vicinity.

According to Strabo the city was known also as "Eusebeia at the Taurus". Under Roman Emperor Caracalla, the city became Antoniana colonia Tyana. After having sided with Queen Zenobia of Palmyra, it was captured by Aurelian in 272, who would not allow his soldiers to sack it, allegedly because Apollonius appeared to him, pleading for its safety.

Late Roman and Byzantine periods: In 372, Emperor Valens split the province of Cappadocia in two, and Tyana became the capital and metropolis of Cappadocia Secunda. In Late Antiquity, the city was also known as Christoupolis (Greek: Χριστούπολις, "city of Christ").[7]

Following the Muslim conquests and the establishment of the frontier between the Byzantine Empire and the Caliphate along the Taurus Mountains, Tyana became important as a military base due to its strategic position on the road to Cilicia and Syria via the Cilician Gates, which lie some 30 km to the south.[8] Consequently, the city was frequently targeted by Muslim raids. The city was first sacked by the Umayyads after a long siege in 708,[9][10] and remained deserted for some time before being rebuilt. It was then occupied by the Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid in 806. Harun began converting the city into a military base and even erected a mosque there, but evacuated it after the Byzantine emperor Nikephoros I bought a peace.[11]

The city was again taken and razed by the Abbasids under Al-Abbas ibn al-Ma'mun in 831.[12] Abbas rebuilt the site three years later as an Abbasid military colony in preparation for Caliph al-Ma'mun's planned conquest of Byzantium, but after Ma'mun's sudden death in August 833 the campaign was abandoned by his successor al-Mu'tasim and the half-rebuilt city was razed again.[13]

The city fell into decline after 933, as the Arab threat receded.[14] The ruins of Tyana are at modern Kemerhisar, three miles south of Niğde;[15] there are remains of a Roman aqueduct and of cave cemeteries and sepulchral grottoes.

Mention by Pliny

Pliny[16] mentions....In its (Cappadocia) remaining districts there is Melita,8 founded by Semiramis, and not far from the Euphrates, Diocæsarea,9 Tyana,10 Castabala,11 Magnopolis,12 Zela,13 and at the foot of Mount Argæus14 Mazaca, now called Cæsarea.15

8 Which gave name to the district of Melitene, mentioned in c. 20 of the last Book.

9 Near Nazianzus, in Cappadocia, the birth-place of Gregory Nazianzen. The traveller Ainsworth, on his road from Ak Serai to Kara Hissar, came to a place called Kaisar Koi, and he has remarked that by its name and position it might be identified with Diocæsarea. Some geographers, indeed, look upon Diocæsarea and Nazianzus as the same place.

10 Its ruins are still to be seen at Kiz Hisar. It stood in the south of Cappadocia, at the northern foot of Mount Taurus. Tyana was the native place of Apollonius, the supposed worker of miracles, whom the enemies of Christianity have not scrupled to place on a par with Jesus Christ.

11 Some ruins, nineteen geographical miles from Ayas, are supposed to denote the site of ancient Castabala or Castabulum.

12 This place was first called Eupatoria, but not the same which Mithridates united with a part of Amisus. D'Anville supposes that the modern town of Tchenikeb occupies its site.

13 Or Ziela, now known as Zillah, not far south of Amasia. It was here that Julius Cæsar conquered Pharnaces, on the occasion on which he wrote his dispatch to Rome, "Veni, vidi, vici."

14 Still known by the name of Ardgeh-Dagh.

15 Its site is still called Kaisiriyeh. It was a city of the district Cilicia, in Cappadocia, at the base of the mountain Argæus. It was first called Mazaca, and after that, Eusebeia. There are considerable remains of the ancient city.

References

- ↑ Bryce, Trevor R; 2003. in C. Melchert (ed.) The Luvians. Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers: 47

- ↑ Singer, Itamar; 1981. Hittites and Hattians in Anatolia at the Beginning of the Second Millennium B.C. Journal of Near Eastern Studies 9: 119-134.

- ↑ Bryce, Trevor R; 2003. in C. Melchert (ed.) The Luvians. Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers: 97-8

- ↑ http://www.hittitemonuments.com/ivriz/

- ↑ Bryce, Trevor R; 2003. in C. Melchert (ed.) The Luvians. Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers: 98

- ↑ http://www.hittitemonuments.com/nigde/

- ↑ Kazhdan, Alexander, ed. (1991). The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-504652-8. p. 2130

- ↑ Kazhdan (1991), p. 2130

- ↑ Kazhdan (1991), p. 2130

- ↑ Treadgold, Warren (1988). The Byzantine Revival, 780–842. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-1462-4. p. 275–276

- ↑ Treadgold (1988), p. 145

- ↑ Treadgold (1997), p. 341

- ↑ Treadgold (1988), pp. 279–281

- ↑ Kazhdan (1991), p. 2130

- ↑ Kazhdan (1991), p. 2130

- ↑ Natural History by Pliny Book VI/Chapter 3

Back to Jat Places in Turkey