Trojan War

| Author: Laxman Burdak, IFS (R). |

.

Trojan War was waged against the city of Troy by the Achaeans (Greeks) after Paris of Troy took Helen from her husband Menelaus, king of Sparta. The war is one of the most important events in Greek mythology and has been narrated through many works of Greek literature, most notably Homer's Iliad. The core of the Iliad (Books II – XXIII) describes a period of four days and two nights in the tenth year of the decade-long siege of Troy; the Odyssey describes the journey home of Odysseus, one of the war's heroes. Other parts of the war are described in a cycle of epic poems, which have survived through fragments. Episodes from the war provided material for Greek tragedy and other works of Greek literature, and for Roman poets including Virgil and Ovid.

Location

The Troy city situated in the far northwest of the region known as Asia Minor, now known as Anatolia in modern Turkey. Troy was the venue of the Trojan War.

History

The war originated from a quarrel between the goddesses Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite, after Eris, the goddess of strife and discord, gave them a golden apple, sometimes known as the Apple of Discord, marked "for the fairest". Zeus sent the goddesses to Paris, who judged that Aphrodite, as the "fairest", should receive the apple. In exchange, Aphrodite made Helen, the most beautiful of all women and wife of Menelaus, fall in love with Paris, who took her to Troy. Agamemnon, king of Mycenae and the brother of Helen's husband Menelaus, led an expedition of Achaean troops to Troy and besieged the city for ten years because of Paris' insult. After the deaths of many heroes, including the Achaeans Achilles and Ajax, and the Trojans Hector and Paris, the city fell to the ruse of the Trojan Horse. The Achaeans slaughtered the Trojans (except for some of the women and children whom they kept or sold as slaves) and desecrated the temples, thus earning the gods' wrath. Few of the Achaeans returned safely to their homes and many founded colonies in distant shores. The Romans later traced their origin to Aeneas, Aphrodite's son and one of the Trojans, who was said to have led the surviving Trojans to modern-day Italy.

The ancient Greeks believed that Troy was located near the Dardanelles and that the Trojan War was a historical event of the 13th or 12th century BC, but by the mid-19th century, both the war and the city were widely seen as non-historical. In 1868, however, the German archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann met Frank Calvert, who convinced Schliemann that Troy was a real city at what is now Hissarlik in Turkey.[1] On the basis of excavations conducted by Schliemann and others, this claim is now accepted by most scholars.[2][3]

Whether there is any historical reality behind the Trojan War remains an open question. Many scholars believe that there is a historical core to the tale, though this may simply mean that the Homeric stories are a fusion of various tales of sieges and expeditions by Mycenaean Greeks during the Bronze Age. Those who believe that the stories of the Trojan War are derived from a specific historical conflict usually date it to the 12th or 11th centuries BC, often preferring the dates given by Eratosthenes, 1194–1184 BC, which roughly corresponds with archaeological evidence of a catastrophic burning of Troy VII.[4]

Sack of Troy

The Achaeans entered the city and killed the sleeping population. A great massacre followed which continued into the day.

- Blood ran in torrents, drenched was all the earth,

- As Trojans and their alien helpers died.

- Here were men lying quelled by bitter death

- All up and down the city in their blood.[5]

The Trojans, fuelled with desperation, fought back fiercely, despite being disorganized and leaderless. With the fighting at its height, some donned fallen enemies' attire and launched surprise counterattacks in the chaotic street fighting. Other defenders hurled down roof tiles and anything else heavy down on the rampaging attackers. The outlook was grim though, and eventually the remaining defenders were destroyed along with the whole city.

Neoptolemus killed Priam, who had taken refuge at the altar of Zeus of the Courtyard.[154][162] Menelaus killed Deiphobus, Helen's husband after Paris' death, and also intended to kill Helen, but, overcome by her beauty, threw down his sword[163] and took her to the ships.[6]

Ajax the Lesser raped Cassandra on Athena's altar while she was clinging to her statue. Because of Ajax's impiety, the Acheaens, urged by Odysseus, wanted to stone him to death, but he fled to Athena's altar, and was spared.[7]

Antenor, who had given hospitality to Menelaus and Odysseus when they asked for the return of Helen, and who had advocated so, was spared, along with his family.[166] Aeneas took his father on his back and fled, and, according to Apollodorus, was allowed to go because of his piety.[162]

The Greeks then burned the city and divided the spoils. Cassandra was awarded to Agamemnon. Neoptolemus got Andromache, wife of Hector, and Odysseus was given Hecuba, Priam's wife.[167]

The Achaeans[8] threw Hector's infant son Astyanax down from the walls of Troy,[9] either out of cruelty and hate[10] or to end the royal line, and the possibility of a son's revenge.[11] They (by usual tradition Neoptolemus) also sacrificed the Trojan princess Polyxena on the grave of Achilles as demanded by his ghost, either as part of his spoil or because she had betrayed him.[12]

Aethra, Theseus' mother, and one of Helen's handmaids, was rescued by her grandsons, Demophon and Acamas.[13]

Migration of Nagas to India

Dr Naval Viyogi[14] writes that....Certain Nagavanshi tribes of Assyria or Sumer came to India along with the names of their kings in a period after 3000 B. C. or roughly Indus Valley period (2700-1600 BC). Either the knowledge of Nagavanshi names and words was transferred to ojhas or priests or they were themselves among the immigrants. Although it is a farfetched idea, yet I think this will be the most acceptable view-point, because verses were composed at a very later period, the composer would have belonged to the institution of immigrant priest class. It is equally possible that Atharv-Veda would have been related to the black section of Rishi of Assyrian immigrants like wise a section of Yajurveda or Kanva as suggested by some scholars[15]. There are clear evidences of Indus seals or seal Impressions with figures of Nagas or serpents depicted on them. Similarly there is another supporting evidence of Rigvedic description (lV-28-l) of Nagas also. [16]

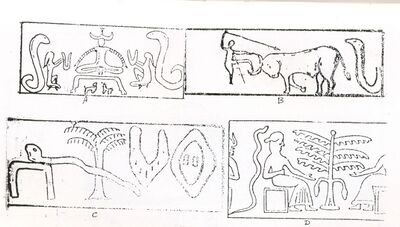

To understand this important secret we have to study the available evidences of Naga worship in Babylonia, Sumer and Assyria. (see Illustration Naga Seals from Indus Valley) James Fergusson [17] produces detail of such evidences as under,

- "In addition to the Tyrian coins and other monuments which in themselves would suffice to prove the prevalence of serpent worship on the seaboard of Syria, we have a direct testimony in a quotation from Sanchoniathon, an author who is supposed to have lived before the Trojan War. This passage is in itself sufficient to throw light on the feelings of the ancients on this subject. It may be worthwhile to quote it fully. Taautus attributed a certain divine nature to dragons and serpents, an opinion which was afterwards adopted both by the phoenicians and Egyptians. He teaches that this genus of animals abounds in force and spirit more than any other reptiles; that there is something fiery in their nature, and though possessing neither feet nor any external members for motion common to other animals, they are yet more rapid in their motion than any other. Not only has it the power of renewing its youth, but in doing so receives an increase of size and strength, so that after having run through a certain term of years it is again absorbed within itself. For these reasons this class of animals was admitted into temples, and used in sacred mysteries. By the Phoenicians they were called the good demon, which was the term also applied by the Egyptians to Cneph. who added to him the head of a hawk to symbolize the vivacity of that bird.

External links

References

- ↑ Bryce, Trevor (2005). The Trojans and their neighbours. Taylor & Francis. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-415-34959-8.

- ↑ Rutter, Jeremy B. "Troy VII and the Historicity of the Trojan War". Retrieved 2007-07-23.

- ↑ Wood, Michael (1998). "Preface". In Search of the Trojan War (2 ed.). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. p. 4. ISBN 0-520-21599-0.

- ↑ Wood (1985: 116–118)

- ↑ Quintus Smyrnaeus, Posthomerica xiii.100–104, Translation by A.S. Way, 1913.

- ↑ Proclus, Chrestomathy 4, Iliou Persis.

- ↑ Proclus, Chrestomathy 4, Iliou Persis.

- ↑ Proclus, Chrestomathy 4, Ilio Persis, says Odysseus killed Astyanax, while Pausanias, 10.25.9, says Neoptolemus.

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 5.23.

- ↑ Quintus Smyrnaeus, Posthomerica xiii.279–285.

- ↑ Euripides, Trojan Women 709–739, 1133–1135; Hyginus, Fabulae 109.

- ↑ Euripides, Hecuba 107–125, 218–224, 391–393, 521–582; Quintus Smyrnaeus, Posthomerica xiv.193–328.

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 5.22; Pausanias, 10.25.8; Quintus Smyrnaeus, Posthomerica xiii.547–595.

- ↑ Dr Naval Viyogi: Nagas – The Ancient Rulers of India, p.12

- ↑ Chanda RP "Ibid" IC 25

- ↑ Dr Naval Viyogi: Nagas – The Ancient Rulers of India, p.11

- ↑ James Fergusson:Tree and Serpent Worship, P-10