Sumer

Sumer (Hindi:सुमेर Akkadian: Šumeru) meaning "land of the civilized lords" or "native land".

History

It was a civilization and historical region in southern Mesopotamia, modern Iraq during the Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age. Although the earliest historical records in the region do not go back much further than ca. 2900 BC, modern historians have asserted that Sumer was first settled between ca. 4500 and 4000 BC by a non-Semitic people who possibly did not speak the Sumerian language (pointing to the names of cities, rivers, basic occupations, etc. as evidence).[1] These conjectured, prehistoric people are now called "proto-Euphrateans" or " Ubaidians", and are theorized to have evolved from the Samarra culture of northern Mesopotamia. The Ubaidians were the first civilizing force in Sumer, draining the marshes for agriculture, developing trade, and establishing industries, including weaving, leatherwork, metalwork, masonry, and pottery.[3] However, some, such as Piotr Michalowski and Gerd Steiner, contest the idea of a Proto-Euphratean language or one substrate language.

Sumerian civilization took form in the Uruk period (4th millennium BC), continuing into the Jemdat Nasr and Early Dynastic periods. It was conquered by the Semitic-speaking kings of the Akkadian Empire around 2270 BC (short chronology). Native Sumerian rule re-emerged for about a century in the third dynasty of Ur (Sumerian Renaissance) of the 21st to 20th centuries BC. The cities of Sumer were the first civilization to practice intensive, year-round agriculture, by perhaps c. 5000 BC showing the use of core agricultural techniques, including large-scale intensive cultivation of land, mono-cropping, organized irrigation, and the use of a specialized labour force. The surplus of storable food created by this economy allowed the population to settle in one place, instead of migrating after crops and grazing land. It also allowed for a much greater population density, and in turn required an extensive labour force and division of labour. Sumer was also the site of early development of writing, progressing from a stage of proto-writing in the mid 4th millennium BC to writing proper in the third millennium

Migration of Nagas to India

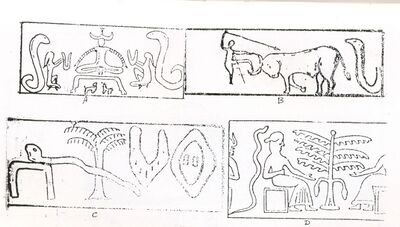

Dr Naval Viyogi[2] writes that....Certain Nagavanshi tribes of Assyria or Sumer came to India along with the names of their kings in a period after 3000 B. C. or roughly Indus Valley period (2700-1600 BC). Either the knowledge of Nagavanshi names and words was transferred to ojhas or priests or they were themselves among the immigrants. Although it is a farfetched idea, yet I think this will be the most acceptable view-point, because verses were composed at a very later period, the composer would have belonged to the institution of immigrant priest class. It is equally possible that Atharv-Veda would have been related to the black section of Rishi of Assyrian immigrants like wise a section of Yajurveda or Kanva as suggested by some scholars[3]. There are clear evidences of Indus seals or seal Impressions with figures of Nagas or serpents depicted on them. Similarly there is another supporting evidence of Rigvedic description (lV-28-l) of Nagas also. [4]

To understand this important secret we have to study the available evidences of Naga worship in Babylonia, Sumer and Assyria. (see Illustration Naga Seals from Indus Valley) James Fergusson [5] produces detail of such evidences as under,

- "In addition to the Tyrian coins and other monuments which in themselves would suffice to prove the prevalence of serpent worship on the seaboard of Syria, we have a direct testimony in a quotation from Sanchoniathon, an author who is supposed to have lived before the Trojan War. This passage is in itself sufficient to throw light on the feelings of the ancients on this subject. It may be worthwhile to quote it fully. Taautus attributed a certain divine nature to dragons and serpents, an opinion which was afterwards adopted both by the phoenicians and Egyptians. He teaches that this genus of animals abounds in force and spirit more than any other reptiles; that there is something fiery in their nature, and though possessing neither feet nor any external members for motion common to other animals, they are yet more rapid in their motion than any other. Not only has it the power of renewing its youth, but in doing so receives an increase of size and strength, so that after having run through a certain term of years it is again absorbed within itself. For these reasons this class of animals was admitted into temples, and used in sacred mysteries. By the Phoenicians they were called the good demon, which was the term also applied by the Egyptians to Cneph. who added to him the head of a hawk to symbolize the vivacity of that bird.

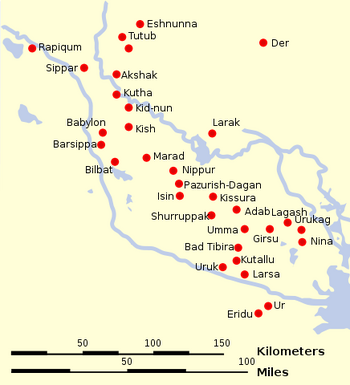

Cities of Sumer

By the late 4th millennium BC, Sumer was divided into about a dozen independent city-states, which were divided by canals and boundary stones. Each was centered on a temple dedicated to the particular patron god or goddess of the city and ruled over by a priestly governor or by a king (lugal) who was intimately tied to the city's religious rites.

|

The five "first" cities said to have exercised pre-dynastic kingship:

Other principal cities:

(1location uncertain) |

Minor cities (from south to north):

(2an outlying city in northern Mesopotamia) |

Apart from Mari, which lies full 330|km northwest of Agade, but which is credited in the Sumerian king list as having “exercised kingship” in the Early Dynastic II period, and Nagar, an outpost, these cities are all in the Euphrates-Tigris alluvial plain, south of Baghdad in what are now the Babil, Diyala, Wasit, Dhi Qar, Basra, Al-Muthannā and Al-Qādisiyyah governorates of Iraq.

Sumerian deities

The Sumerians worshipped:

- Anu as the full time god, equivalent to "heaven" - indeed, the word "an" in Sumerian means "sky" and his consort Ki, means "Earth".

- Enki in the south at the temple in Eridu. Enki was the god of beneficence, ruler of the freshwater depths beneath the earth, a healer and friend to humanity who in Sumerian myth was thought to have given humans the arts and sciences, the industries and manners of civilization; the first law-book was considered his creation,

- Enlil, lord of the ghost-land, in the north at the temple of Nippur. His gifts to mankind were said to be the spells and incantations that the spirits of good or evil were compelled to obey,

- Inanna, the deification of Venus, the morning (eastern) and evening (western) star, at the temple (shared with An) at Uruk.

These deities were probably the original matrix;there were hundreds of minor deities. The Sumerian gods thus had associations with different cities, and their religious importance often waxed and waned with those cities' political power. The gods were said to have created human beings from clay for the purpose of serving them. If the temples/gods ruled each city it was for their mutual survival and benefit—the temples organized the mass labor projects needed for irrigation agriculture. Citizens had a labor duty to the temple which they were allowed to avoid by a payment of silver only towards the end of the third millennium. The temple-centered farming communities of Sumer had a social stability that enabled them to survive for four millennia.

Sumerian Agriculture

By 5000 BC the Sumerians had developed core agricultural techniques including large-scale intensive cultivation of land, mono-cropping, organized irrigation, and the use of a specialized labour force, particularly along the waterway now known as the Shatt al-Arab, from its Persian Gulf delta to the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates. The surplus of storable food created by this economy allowed the population to settle in one place instead of migrating after crops and grazing land. It also allowed for a much greater population density, and in turn required an extensive labor force and division of labor. This organization led to the development of writing (ca. 3500 BC).

The Sumerians adopted an agricultural mode of life. In the early Sumerian period (i.e. Uruk), the primitive pictograms suggest that "The sheep, goat, ox and probably ass had been domesticated, the ox being used for draught, and woollen clothing as well as rugs were made from the wool or hair of the two first. ... By the side of the house was an enclosed garden planted with trees and other plants ; wheat and probably other cereals were sown in the fields, and the shaduf was already employed for the purpose of irrigation. Plants were also grown in pots or vases."[6]

The Sumerians practiced the same irrigation techniques as those used in Egypt.[7] American anthropologist Robert McCormick Adams says that irrigation development was associated with urbanization, and that 89% of the population lived in the cities.

They grew barley, chickpeas, lentils, wheat, dates, onions, garlic, lettuce, leeks and mustard. They also raised cattle, sheep, goats, and pigs. They used oxen as their primary beasts of burden and donkeys or equids as their primary transport animal. Sumerians caught many fish and hunted fowl and gazelle.

Sumerian agriculture depended heavily on irrigation. The irrigation was accomplished by the use of shadufs, canals, channels, dykes, weirs, and reservoirs. The frequent violent floods of the Tigris, and less so, of the Euphrates, meant that canals required frequent repair and continual removal of silt, and survey markers and boundary stones continually replaced. The government required individuals to work on the canals in a corvee, although the rich were able to exempt themselves.

After the flood season and after the Spring Equinox and the Akitu or New Year Festival, using the canals, farmers would flood their fields and then drain the water. Next they let oxen stomp the ground and kill weeds. They then dragged the fields with pickaxes. After drying, they plowed, harrowed, and raked the ground three times, and pulverized it with a mattock, before planting seed. Unfortunately the high evaporation rate resulted in a gradual increase in the salinity of the fields. By the Ur III period, farmers had switched from wheat to the more salt-tolerant barley as their principal crop.

Sumerians harvested during the spring in three-person teams consisting of a reaper, a binder, and a sheaf handler. The farmers would use threshing wagons to separate the cereal heads from the stalks and then use threshing sleds to disengage the grain. They then winnowed the grain/chaff mixture.

World Heritage status

"The Heart of Neolithic Orkney" was inscribed as a World Heritage site in December 1999. In addition to Skara Brae the site includes Maeshowe, the Ring of Brodgar, the Standing Stones of Stenness and other nearby sites. It is managed by Historic Scotland, whose "Statement of Significance" for the site begins:

- The monuments at the heart of Neolithic Orkney and Skara Brae proclaim the triumphs of the human spirit in early ages and isolated places. They were approximately contemporary with the mastabas of the archaic period of Egypt (first and second dynasties), the brick temples of Sumeria, and the first cities of the Harappa culture in India, and a century or two earlier than the Golden Age of China. Unusually fine for their early date, and with a remarkably rich survival of evidence, these sites stand as a visible symbol of the achievements of early peoples away from the traditional centres of civilisation.[8]

References

- ↑ Bertman, Stephen (2003). Handbook to life in ancient Mesopotamia. Facts on File. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-8160-4346-0

- ↑ Dr Naval Viyogi: Nagas – The Ancient Rulers of India, p.12

- ↑ Chanda RP "Ibid" IC 25

- ↑ Dr Naval Viyogi: Nagas – The Ancient Rulers of India, p.11

- ↑ James Fergusson:Tree and Serpent Worship, P-10

- ↑ Sayce, Rev. A. H. (1908). The Archaeology of the Cuneiform Inscriptions" (2nd revised ed.). London, Brighton, New York: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. pp. 98-100.

- ↑ Mackenzie, Donald Alexander (1927). Footprints of Early Man. Blackie & Son Limited.

- ↑ "The Heart of Neolithic Orkney". Historic Scotland. Archived from the original on 11 September 2007.