Characene

| Author:Laxman Burdak, IFS (R) |

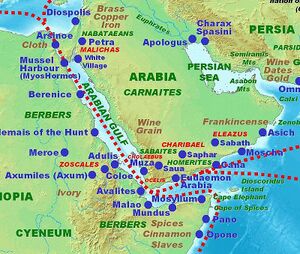

Characene was a kingdom founded by the Iranian[1]Hyspaosines located at the head of the Persian Gulf mostly within modern day Iraq. Its capital, Charax Spasinou (Χάραξ Σπασινού), was an important port for trade between Mesopotamia and India, and also provided port facilities for the city of Susa further up the Karun River. The kingdom was frequently a vassal of the Parthian Empire. Characene was mainly populated by Arabs, who spoke Aramaic as their cultural language.[2] All rulers of the principality had Iranian names.[3] Members of the Arsacid dynasty also ruled the state.[4]

It is also called Mesene as mentioned by Pliny (Pliny.vi.31).

Variants

- Mesene (Μεσσήνη)[5] - "Mesene" is seemingly of Persian origin, meaning "land of buffalos" or the "land of sheep."[6]

- Meshan

- Characene (Ancient Greek: Χαρακηνή) (Pliny.vi.29)

- Hrva (हृव) or Urva (उर्व) identified by some with ‘Mesene, the region of the lower Eupharates’ or by others with the valley of Kabul. [7]

Name

The name "Characene" originated from the name of the capital of the kingdom, Charax Spasinu. The kingdom was also known by the older name of the region, "Mesene", which is seemingly of Persian origin, meaning "land of buffalos" or the "land of sheep."[8]

Jat Gotras Namesake

- Bains = Bhains (hindi) = Mesene (Persian, meaning "land of buffalos") (Pliny.vi.31). Bains is prakrat form of buffalo. Pliny mentions a town on the bank of Tigris named Mesene (Pliny.vi.31); Mesene (Μεσσήνη)[9]. "Mesene" is seemingly of Persian origin, meaning "land of buffalos" or the "land of sheep."[10]

- Bhains (hindi) = Mesene (Persian, meaning "land of buffalos") (Pliny.vi.31). Bains is prakrat form of buffalo. Pliny mentions a town on the bank of Tigris named Mesene (Pliny.vi.31); Mesene (Μεσσήνη)[11]. "Mesene" is seemingly of Persian origin, meaning "land of buffalos" or the "land of sheep."[12]

- Char = Characene (Ancient Greek: Χαρακηνή) (Pliny.vi.29) = Mesene (Pliny.vi.31)

- Charaka = Characene (Ancient Greek: Χαρακηνή) (Pliny.vi.29) = Mesene (Pliny.vi.31)

History

The capital of Characene, Alexandria, was originally founded by the Macedonian ruler Alexander the Great, with the intention of using the town as a leading commercial port for his eastern capital of Babylon.[13] The region itself became the Satrapy of the Erythraean Sea.[14] However, the city never lived up to its expectations, and was destroyed in the mid 3rd-century BC by floods.[15] It was not until the reign of the Seleucid king Antiochus IV Epiphanes (r. 175 – 164 BC) that the city was rebuilt and renamed Antiochia.[16] After the city was fully restored in 166/5 BC, Antiochus IV appointed Hyspaosines as governor (eparch) of Antiochia and the Satrapy of the Erythraean Sea.[17]

During this period Antiochia briefly flourished, until Antiochus IV's abrupt death in 163 BC, which weakened Seleucid authority throughout the empire. With the weakening of the Seleucids, many political entities within the empire declared independence, such as the neighbouring region of Characene, Elymais, which was situated in most of the present-day province of Khuzestan in southern Iran. Hyspaosines, although now a more or less independent ruler, remained a loyal subject of the Seleucids. Hyspaosines' keenness to remain as a Seleucid governor was possibly due to avoid interruption in the profitable trade between Antiochia and Seleucia.[18]

The Seleucids had suffered heavy defeats by the Iranian Parthian Empire; in 148/7 BC, the Parthian king Mithridates I (r. 171–132 BC) conquered Media and Atropatene, and by 141 BC, was in the possession of Babylonia.[19] The menace and proximity of the Parthians caused Hyspaosines to declare independence.[20] In 124 BC, however, Hyspaosines accepted Parthian suzerainty, and continued to rule Characene as a vassal.[21] Characene would generally remain a semi-autonomous kingdom under Parthian suzerainty till its fall. The realm of the kingdom included the islands Failaka and Bahrain.[22]

The kings of Characene are known mainly by their coins, consisting mainly of silver tetradrachms with Greek and later Aramaic inscriptions. These coins are dated after the Seleucid era, providing a secure framework for chronological succession.

Mention by Pliny

Pliny[23] mentions Tigris....After traversing the mountains of the Gordyæi13, it passes round Apamea14, a town of Mesene, one hundred and twenty-five miles on this side of Babylonian Seleucia, and then divides into two channels, one15 of which runs southward, and flowing through Mesene, runs towards Seleucia, while the other takes a turn to the north and passes through the plains of the Cauchæ16, at the back of the district of Mesene. When the waters have reunited, the river assumes the name of Pasitigris.

13 See c. 17 of the present Book.

14 The site of this place seems to be unknown. It has been remarked that it is difficult to explain the meaning of this passage of Pliny, or to determine the probable site of Apamea.

15 Hardouin remarks that this is the right arm of the Tigris, by Stephanus Byzantinus called Delas, and by Eustathius Sylax, which last he prefers.

16 According to Ammianus, one of the names of Seleucia on the Tigris was Coche.

Mention by Pliny

Pliny[24] mentions The Tigris....The country on the banks of the Tigris is called Parapotamia19; we have already made mention of Mesene, one of its districts. Dabithac20 is a town there, adjoining to which is the district of Chalonitis, with the city of Ctesiphon21, famous, not only for its palm-groves, but for its olives, fruits, and other shrubs. Mount Zagrus22 reaches as far as this district, and extends from Armenia between the Medi and the Adiabeni, above Parætacene and Persis. Chalonitis23 is distant from Persis three hundred and eighty miles; some writers say that by the shortest route it is the same distance from Assyria and the Caspian Sea.

19 Or the country "by the river."

20 Pliny is the only writer who makes mention of this place. Parisot is of opinion that it is represented by the modern Digil-Ab, on the Tigris, and suggests that Digilath may be the correct reading.

21 Mentioned in the last Chapter.

22 Now called the Mountains of Luristan.

23 The name of the district of Chalonitis is supposed to be still preserved in that of the river of Holwan. Pliny is thought, however, to have been mistaken in placing the district on the river Tigris, as it lay to the east of it, and close to the mountains.

References

- ↑ Hansman 1991, pp. 363–365; Eilers 1983, p. 487; Erskine, Llewellyn-Jones & Wallace 2017, p. 77; Strootman 2017, p. 194

- ↑ Bosworth, C. E. (1986). "ʿArab i. Arabs and Iran in the pre-Islamic period". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 2. pp. 201–203

- ↑ Eilers, Wilhelm (1983), "Iran and Mesopotamia", in Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.), Cambridge History of Iran, vol. 3, London: Cambridge UP, p. 487

- ↑ Gregoratti, Leonardo (2017). "The Arsacid Empire". In Daryaee, Touraj (ed.). King of the Seven Climes: A History of the Ancient Iranian World (3000 BCE - 651 CE). UCI Jordan Center for Persian Studies. p. 133, ISBN 9780692864401.

- ↑ Morony, Michael G. (2005). Iraq After The Muslim Conquest. Gorgias Press LLC. p. 155. ISBN 9781593333157.

- ↑ Gnoli, Tommaso (2022). "The Parthian and Sasanian Near East (including Hatra, Edessa, and the Characene)". In Kaizer, Ted (ed.). A Companion to the Hellenistic and Roman Near East. John Wiley & Sons. p. 319, ISBN 978-1444339826.

- ↑ परोपकारी, अप्रेल प्रथम 2019, s.n. 8, p.6

- ↑ Gnoli, Tommaso (2022). "The Parthian and Sasanian Near East (including Hatra, Edessa, and the Characene)". In Kaizer, Ted (ed.). A Companion to the Hellenistic and Roman Near East. John Wiley & Sons. p. 319, ISBN 978-1444339826.

- ↑ Morony, Michael G. (2005). Iraq After The Muslim Conquest. Gorgias Press LLC. p. 155. ISBN 9781593333157.

- ↑ Gnoli, Tommaso (2022). "The Parthian and Sasanian Near East (including Hatra, Edessa, and the Characene)". In Kaizer, Ted (ed.). A Companion to the Hellenistic and Roman Near East. John Wiley & Sons. p. 319, ISBN 978-1444339826.

- ↑ Morony, Michael G. (2005). Iraq After The Muslim Conquest. Gorgias Press LLC. p. 155. ISBN 9781593333157.

- ↑ Gnoli, Tommaso (2022). "The Parthian and Sasanian Near East (including Hatra, Edessa, and the Characene)". In Kaizer, Ted (ed.). A Companion to the Hellenistic and Roman Near East. John Wiley & Sons. p. 319, ISBN 978-1444339826.

- ↑ Hansman, John (1991). "Characene and Charax". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. V, Fasc. 4. pp. 363–365.

- ↑ Potts, Daniel T. (1988). Araby the blest : studies in Arabian archaeology. Copenhagen: Carsten Niebuhr Institute of Ancient Near Eastern Studies. ISBN 8772890517. p. 137.

- ↑ Hansman 1991, pp. 363–365.

- ↑ Hansman 1991, pp. 363–365.

- ↑ Potts 1988, pp. 137–138.

- ↑ Hansman 1991, pp. 363–365.

- ↑ Curtis 2007, pp. 10–11; Bivar 1983, p. 33; Garthwaite 2005, p. 76; Brosius 2006, pp. 86–87

- ↑ Hansman 1991, pp. 363–365.

- ↑ Shayegan, M. Rahim (2011). Arsacids and Sasanians: Political Ideology in Post-Hellenistic and Late Antique Persia. Cambridge University Press. pp. 114. ISBN 9780521766418.

- ↑ Pierre-Louis Gatier, Pierre Lombard, Khaled Al-Sindi (2002)ː Greek Inscriptions from Bahrain. inː Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy, Wiley, 2002, 13 (2), pp.225.

- ↑ Natural History by Pliny Book VI/Chapter 31

- ↑ Natural History by Pliny Book VI/Chapter 31

Back to Jat Places in Iraq