Chauvet

Chauvet Cave or Chauvet-Pont-d'Arc Cave in the Ardèche department of southern France is a cave that contains some of the best-preserved figurative cave paintings in the world,[1] as well as other evidence of Upper Paleolithic life.[2]

Variations

Location

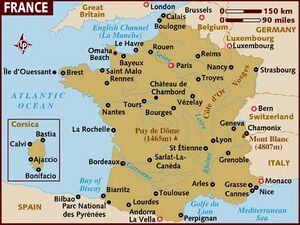

Ardèche (French pronunciation: [aʁdɛʃ]; Occitan and Arpitan: Ardecha) is a department in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region of Southeast France. It is named after the River Ardèche and had a population of 320,379 as of 2013. Its largest cities are Aubenas, Annonay, Guilherand-Granges, Tournon-sur-Rhône and Privas (prefecture).

Chauvet Cave is located near the commune of Vallon-Pont-d'Arc on a limestone cliff above the former bed of the Ardèche River, in the Gorges de l'Ardèche.

Features

Discovered by Christian Hillaire, Eliette Brunel Deschamps and Jean-Marrie Chauvet on December 18, 1994, is known as Cave of Forgotten Dreams.[3] It is considered one of the most significant prehistoric art sites and the UN’s cultural agency UNESCO granted it World Heritage status on June 22, 2014.[4] The cave was first explored by a group of three speleologists: Eliette Brunel-Deschamps, Christian Hillaire, and Jean-Marie Chauvet for whom it was named six months after an aperture now known as "Le Trou de Baba" was discovered by Michel Rosa (Baba).[5] At a later date the group returned to the cave. Another member of this group, Michel Chabaud, along with two others, travelled further into the cave and discovered the Gallery of the Lions, the End Chamber. In doing so they became the first people in 30000 years to cast eyes on these paintings. Chauvet has his own detailed account of the discovery.[6] In addition to the paintings and other human evidence, they also discovered fossilized remains, prints, and markings from a variety of animals, some of which are now extinct.

The cave is situated above the previous course of the Ardèche River before the Pont d'Arc opened up. The gorges of the Ardèche region are the site of numerous caves, many of them having some geological or archaeological importance.

Based on radiocarbon dating, the cave appears to have been used by humans during two distinct periods: the Aurignacian and the Gravettian. Most of the artwork dates to the earlier, Aurignacian, era (30,000 to 32,000 years ago). The later Gravettian occupation, which occurred 25,000 to 27,000 years ago, left little but a child's footprints, the charred remains of ancient hearths[citation needed], and carbon smoke stains from torches that lit the caves. The footprints may be the oldest human footprints that can be dated accurately. After the child's visit to the cave, evidence suggests that due to a landslide which covered its historical entrance, the cave remained untouched until it was discovered in 1994.[7]

The soft, clay-like floor of the cave retains the paw prints of cave bears along with large, rounded depressions that are believed to be the "nests" where the bears slept. Fossilized bones are abundant and include the skulls of cave bears and the horned skull of an ibex.[8] A set of foot prints of a young child and a wolf or dog walking side by side was found in this cave. This information suggests the origin of the domestic dog could date to before the last Ice Age.[9]

Further study by French archaeologist Jean Clottes has revealed much about the site. The dates have been a matter of dispute but a study published in 2012 supports placing the art in the Aurignacian period, approximately 32,000–30,000 years BP. A study published in 2016 using additional 88 radiocarbon dates showed two periods of habitation, one 37,000 to 33,500 years ago and the second from 31,000 to 28,000 years ago with most of the black drawings dating to the earlier period.

Paintings

Hundreds of animal paintings have been catalogued, depicting at least 13 different species, including some rarely or never found in other ice age paintings. Rather than depicting only the familiar herbivores that predominate in Paleolithic cave art, i.e. horses, cattle, mammoths, etc., the walls of the Chauvet Cave feature many predatory animals, e.g., cave lions, panthers, bears, and cave hyenas. There are also paintings of rhinoceroses.[10]

It seems that Chauvet was painted in two distinct periods. The earlier was around 30,000 BC and the later around 25,000 BC. In the far chamber the archaeologists found the foot prints of a little boy walking in the darkness across the clay floor, deduced to have been about 8 years old, may have been one of the last people to see the paintingsbefore the rockfell sealed the cave, around 24000 BC. [11]

Preservation

The cave has been sealed off to the public since 1994. Access is severely restricted owing to the experience with decorated caves such as Altamira and Lascaux found in the 19th and 20th century, where the admission of visitors on a large scale led to the growth of mold on the walls that damaged the art in places. In 2000 the archaeologist and expert on cave paintings Dominique Baffier was appointed to oversee conservation and management of the cave. She was followed in 2014 by Marie Bardisa.

Caverne du Pont-d'Arc, a facsimile of Chauvet Cave on the model of the so-called "Faux Lascaux", was opened to the general public on 25 April 2015.[12] It is the largest cave replica ever built worldwide, ten times bigger than the Lascaux facsimile. The art is reproduced full-size in a condensed replica of the underground environment, in a circular building above ground, a few kilometres from the actual cave.[13] Visitors’ senses are stimulated by the same sensations of silence, darkness, temperature, humidity and acoustics, carefully reproduced.[14]

The DNA Study

Alistair Moffat[15] writes that There is clear link between the pioneers in southern England and the people of the painted caves like Chauvet, Lascaux etc. DNA Strengthens these connections. a very recent sample of 5000 people from all parts of Britain, both men and women - since we all carry mtDNA shows something remarkable. just under 56% of all those tested in 2012 are matrilineally descended from those bands of hunter gatherers who walked North across what is now France, or sailed Atlantic coastline and began to settle in Britain after the ice melted. Those who carry the DNA marker H and it's sub-groups are by far the largest cohort 44%, and Markers U5 and V make up the remainder. The distribution is nationwide from Orkney to Cornwall, and from East Anglia to West Wales. All of these Markers appear to have arisen in the ice age refuges and then fanned out over Europe and Britain after c.9000 BC. The highest modern frequency of H is in Basque County, at the western end of the Pyrenean Ranges, a connection that makes a powerful ancestral link with the cave painters of Chauvet, Lascaux, Altamira and elsewhere.

References

- ↑ UNESCO.

- ↑ Clottes, Jean (2003a). Return To Chauvet Cave, Excavating the Birthplace of Art: The First Full Report. Thames & Hudson. p. 232. ISBN 0-500-51119-5.

- ↑ Alistair Moffat: The British: A Genetic Journey, Birlinn, 2013,ISBN:9781780270753, p.44-45

- ↑ 24. "UNESCO grants heritage status to prehistoric French cave", June 2014.

- ↑ Hammer, Joshua (April 2015). "Finally, the Beauty of France's Chauvet Cave Makes its Grand Public Debut". Smithsonian. Smithsonian Institution.

- ↑ Chauvet, Jean-Marie; Deschamps, Eliette Brunel; Hillaire, Christian; Clottes, Jean; Bahn, Paul (1996). Dawn of art : the Chauvet Cave : the oldest known paintings in the world. New York: H.N. Abrams. ISBN 0-8109-3232-6.

- ↑ Curtis, Gregory (2006). The Cave Painters: Probing the Mysteries of the World's First Artists. New York: Knopf, pp. 215–16.

- ↑ "Smithsonian Magazine, December 2010"

- ↑ Hobgood-Oster, Laura (2014). A Dog's History of the World. Baylor University Press. pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Adams, Laurie (2011). Art Across Time (4th ed.). Mc-Graw Hill. p. 34.

- ↑ Alistair Moffat: The British: A Genetic Journey, Birlinn, 2013,ISBN:9781780270753, p.46-47

- ↑ "Replik der Grotte Chauvet mit Höhlenmalereien". faz.net.

- ↑ "Chauvet-Pont d'Arc cave, grand opening!". TRACCE Online Rock Art Bulletin.

- ↑ "Conservation of prehistoric caves and stability of their inner climate: lessons from Chauvet and other French caves". Bourges F., Genthon P., Genty D., Lorblanchet M., Mauduit E., D’Hulst D. Science of the Total Environment. Vol. 493, 15 Sept. 2014, pp. 79–91 doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.05.137.

- ↑ Alistair Moffat: The British: A Genetic Journey, Birlinn, 2013,ISBN:9781780270753, p.50