Hebrides

Hebrides (/ˈhɛbrɪdiːz/; Scottish Gaelic: Innse Gall, pronounced [ĩːʃə gau̯l̪ˠ]; Old Norse: Suðreyjar) compose a widespread and diverse archipelago off the west coast of mainland Scotland.

Variants of name

Etymology

The earliest written references that have survived relating to the islands were made circa 77 AD by Pliny the Elder in his Natural History, where he states that there are 30 Hebudes, and makes a separate reference to Dumna, which Watson (1926) concludes is unequivocally the Outer Hebrides. Writing about 80 years later, in 140-150 AD, Ptolemy, drawing on the earlier naval expeditions of Agricola, writes that there are five Ebudes (possibly meaning the Inner Hebrides) and Dumna.[1][2][88] Later texts in classical Latin, by writers such as Solinus, use the forms Hebudes and Hæbudes.[3]

The name Ebudes recorded by Ptolemy may be pre-Celtic.[4] Islay is Ptolemy's Epidion,[5] the use of the "p" hinting at a Brythonic or Pictish tribal name, Epidii,[6] although the root is not Gaelic.[7] Woolf (2012) has suggested that Ebudes may be "an Irish attempt to reproduce the word Epidii phonetically rather than by translating it" and that the tribe's name may come from the root epos meaning "horse".[8] Watson (1926) also notes the possible relationship between Ebudes and the ancient Irish Ulaid tribal name Ibdaig and the personal name of a king Iubdán recorded in the Silva Gadelica.[9]

The names of other individual islands reflect their complex linguistic history. The majority are Norse or Gaelic but the roots of several other Hebrides may have a pre-Celtic origin.[10] Adomnán, the 7th century abbot of Iona, records Colonsay as Colosus and Tiree as Ethica, both of which may be pre-Celtic names.[11] The etymology of Skye is complex and may also include a pre-Celtic root.[12] Lewis is Ljoðhús in Old Norse and although various suggestions have been made as to a Norse meaning (such as "song house")[13] the name is not of Gaelic origin and the Norse credentials are questionable.[14]

History

The Hebrides were settled during the Mesolithic era around 6500 BC or earlier, after the climatic conditions improved enough to sustain human settlement. Occupation at a site on Rùm is dated to 8590 ±95 uncorrected radiocarbon years BP, which is amongst the oldest evidence of occupation in Scotland.[15] There are many examples of structures from the Neolithic period, the finest example being the standing stones at Callanish, dating to the 3rd millennium BC.[16] Cladh Hallan, a Bronze Age settlement on South Uist is the only site in the UK where prehistoric mummies have been found.[17]

In 55 BC, the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus wrote that there was an island called Hyperborea (which means "beyond the North Wind"), where a round temple stood from which the moon appeared only a little distance above the earth every 19 years. This may have been a reference to the stone circle at Callanish.[18]

A traveller called Demetrius of Tarsus related to Plutarch the tale of an expedition to the west coast of Scotland in or shortly before AD 83. He stated it was a gloomy journey amongst uninhabited islands, but he had visited one which was the retreat of holy men. He mentioned neither the druids nor the name of the island.[19]

The first written records of native life begin in the 6th century AD, when the founding of the kingdom of Dál Riata took place.[20] This encompassed roughly what is now Argyll and Bute and Lochaber in Scotland and County Antrim in Ireland.[21] The figure of Columba looms large in any history of Dál Riata, and his founding of a monastery on Iona ensured that the kingdom would be of great importance in the spread of Christianity in northern Britain. However, Iona was far from unique. Lismore in the territory of the Cenél Loairn, was sufficiently important for the death of its abbots to be recorded with some frequency and many smaller sites, such as on Eigg, Hinba, and Tiree, are known from the annals.[22]

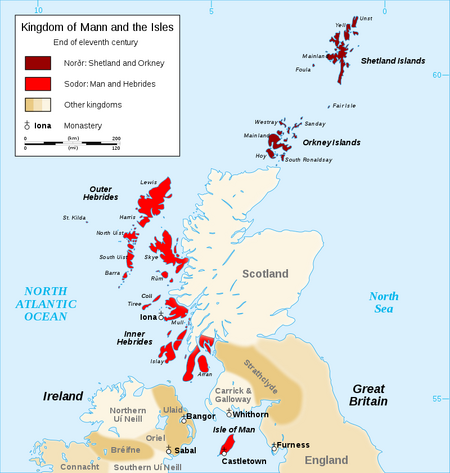

Viking raids began on Scottish shores towards the end of the 8th century and the Hebrides came under Norse control and settlement during the ensuing decades, especially following the success of Harald Fairhair at the Battle of Hafrsfjord in 872.[23] In the Western Isles Ketill Flatnose may have been the dominant figure of the mid 9th century, by which time he had amassed a substantial island realm and made a variety of alliances with other Norse leaders. These princelings nominally owed allegiance to the Norwegian crown, although in practice the latter's control was fairly limited.[24] Norse control of the Hebrides was formalised in 1098 when Edgar of Scotland formally signed the islands over to Magnus III of Norway.[25] The Scottish acceptance of Magnus III as King of the Isles came after the Norwegian king had conquered Orkney, the Hebrides and the Isle of Man in a swift campaign earlier the same year, directed against the local Norwegian leaders of the various island petty kingdoms. By capturing the islands Magnus imposed a more direct royal control, although at a price. His skald Bjorn Cripplehand recorded that in Lewis "fire played high in the heaven" as "flame spouted from the houses" and that in the Uists "the king dyed his sword red in blood".[26]

The Hebrides were now part of the Kingdom of the Isles, whose rulers were themselves vassals of the Kings of Norway. This situation lasted until the partitioning of the Western Isles in 1156, at which time the Outer Hebrides remained under Norwegian control while the Inner Hebrides broke out under Somerled, the Norse-Gael kinsman of the Manx royal house.[27]

Following the ill-fated 1263 expedition of Haakon IV of Norway, the Outer Hebrides and the Isle of Man were yielded to the Kingdom of Scotland as a result of the 1266 Treaty of Perth.[28] Although their contribution to the islands can still be found in personal and place names, the archaeological record of the Norse period is very limited. The best known find is the Lewis chessmen, which date from the mid 12th century.[29]

DNA Evidence

Alistair Moffat[30] notes...Colder and wetter weather in Shetland, Orkney and Hebrides encouraged the spread of peat and in some places the new field boundaries set up by bronze age farmers were submerged across the span of only a few generations. Upland cultivation gave way to stock-rearing and the population dwindled. Some historians believe that the eruption of Hekla triggered a migration from North Western Scotland to the east but at present there exists no firm DNA evidence to support this. The deferences as detected in the east-west frequencies of the subgroups of R1b appear already to have been establishing themselves.

External links

References

- ↑ Breeze, David J. "The ancient geography of Scotland" in Smith and Banks (2002) pp. 11-13

- ↑ Watson, W. J. (1994) The Celtic Place-Names of Scotland. Edinburgh. Birlinn. ISBN 1-84158-323-5. First published 1926. pp. 40–41

- ↑ Watson (1994) p. 38

- ↑ Watson (1994) p. 38

- ↑ Watson (1994) p. 37

- ↑ Watson (1994) p. 45

- ↑ Gammeltoft, Peder "Scandinavian Naming-Systems in the Hebrides - A Way of Understanding how the Scandinavians were in Contact with Gaels and Picts?" in Ballin Smith et al (2007) p. 487

- ↑ Woolf, Alex (2012) Ancient Kindred? Dál Riata and the Cruthin. Academia.edu.

- ↑ Watson (1994) p. 38

- ↑ Watson (1994) p. 38

- ↑ Watson (1994) p. 85-86

- ↑ Gammeltoft, Peder "Scandinavian Naming-Systems in the Hebrides - A Way of Understanding how the Scandinavians were in Contact with Gaels and Picts?" in Ballin Smith et al (2007) p. 487

- ↑ Mac an Tàilleir (2003) p. 80

- ↑ Gammeltoft, Peder "Scandinavian Naming-Systems in the Hebrides - A Way of Understanding how the Scandinavians were in Contact with Gaels and Picts?" in Ballin Smith et al (2007) p. 487

- ↑ 1. Edwards, Kevin J. and Whittington, Graeme "Vegetation Change" in Edwards & Ralston (2003) p. 70 2. Edwards, Kevin J., and Mithen, Steven (Feb., 1995) "The Colonization of the Hebridean Islands of Western Scotland: Evidence from the Palynological and Archaeological Records," World Archaeology. 26. No. 3. p. 348.

- ↑ Li, Martin (2005) Adventure Guide to Scotland. Hunter Publishing. p. 509.

- ↑ 1. "Mummification in Bronze Age Britain" BBC History. 2. "The Prehistoric Village at Cladh Hallan". University of Sheffield.

- ↑ Haycock, David Boyd. "Much Greater, Than Commonly Imagined." Archived 26 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine. The Newton Project.

- ↑ Moffat, Alistair (2005) Before Scotland: The Story of Scotland Before History. London. Thames & Hudson. pp. 239-40.

- ↑ Nieke, Margaret R. "Secular Society from the Iron Age to Dál Riata and the Kingdom of Scots" in Omand (2006) p. 60

- ↑ Lynch (2007) pp. 161 162

- ↑ Clancy, Thomas Owen "Church institutions: early medieval" in Lynch (2001).

- ↑ 1. Rotary Club (1995) p. 12 22. Hunter (2000) p. 78

- ↑ Hunter (2000) p. 78

- ↑ Hunter (2000) p. 102

- ↑ Hunter (2000) p. 102

- ↑ "The Kingdom of Mann and the Isles" thevikingworld.com

- ↑ Hunter (2000) pp. 109-111

- ↑ Thompson (1968) p. 37

- ↑ Alistair Moffat: The British: A Genetic Journey, Birlinn, 2013,ISBN:9781780270753, p.124-125