Cornwall

| Author:Laxman Burdak, IFS (R) |

Cornwall (कॉर्नवल) is a historic county and ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people.

Variants

- Cornish: Kernow [ˈkɛrnɔʊ]

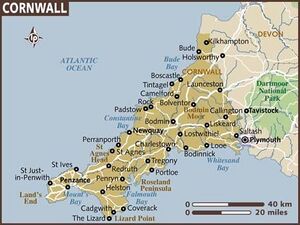

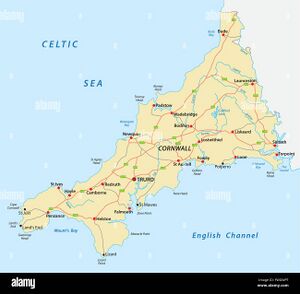

Location

Cornwall is bordered to the north and west by the Atlantic Ocean, to the south by the English Channel, and to the east by the county of Devon, with the River Tamar forming the border between them. Cornwall forms the westernmost part of the South West Peninsula of the island of Great Britain. The southwesternmost point is Land's End and the southernmost Lizard Point. The ceremonial county of Cornwall also includes the Isles of Scilly, which are administered separately. The administrative centre of Cornwall is Truro, its only city.

Name

The modern English name Cornwall is a compound of two ancient demonyms coming from two different language groups: Cornwall = Corn+wall

- Corn- originates from the Proto-Celtic "*karnos" ("horn" or "headland") is cognate with the English word "horn" (both deriving from the Proto-Indo-European *ker-). An Iron Age Celtic tribe that occupied the Cornish peninsula, the Cornovii ("peninsula people") may have also existed.[1][2]

- -wall derives from the Old English exonym "wealh", meaning "foreigner" or "Romanized Celt" (i.e. a Welsh person).[3]

In the Cornish language, Cornwall is Kernow which stems from the same Proto-Celtic root.

Jat clans

History

Cornwall was formerly a Brythonic kingdom and subsequently a royal duchy. It is the cultural and ethnic origin of the Cornish diaspora. The Cornish nationalist movement contests the present constitutional status of Cornwall and seeks greater autonomy within the United Kingdom in the form of a devolved legislative Cornish Assembly with powers similar to those in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland.[4] In 2014, Cornish people were granted minority status under the European Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities,[5] giving them recognition as a distinct ethnic group[6]

Recent discoveries of Roman remains in Cornwall indicate a greater Roman presence there than once thought.[7] After the collapse of the Roman Empire, Cornwall (along with Devon, parts of Dorset and Somerset, and the Scilly Isles) was a part of the Brittonic kingdom of Dumnonia, ruled by chieftains of the Cornovii who may have included figures regarded as semi-historical or legendary, such as King Mark of Cornwall and King Arthur, evidenced by folklore traditions derived from the Historia Regum Britanniae. The Cornovii division of the Dumnonii tribe were separated from their fellow Brythons of Wales after the Battle of Deorham in 577 AD, and often came into conflict with the expanding English kingdom of Wessex. The regions of Dumnonia outside of Cornwall (and Dartmoor) had been annexed by the English by 838 AD.[8] King Athelstan in 936 AD set the boundary between the English and Cornish at the high water mark of the eastern bank of the River Tamar.[9] From the Early Middle Ages, language and culture were shared by Brythons trading across both sides of the Channel, resulting in the corresponding high medieval Breton kingdoms of Domnonée and Cornouaille and the Celtic Christianity common to both areas.

Prehistory, Roman and post-Roman periods

Humans reoccupied Britain after the last Ice Age. The area now known as Cornwall was first inhabited in the Palaeolithic and Mesolithic periods. It continued to be occupied by Neolithic and then by Bronze-Age people.

According to John T. Koch and others, Cornwall in the Late Bronze Age formed part of a maritime trading-networked culture which researchers have dubbed the Atlantic Bronze Age and which extended over the areas of present-day Ireland, England, Wales, France, Spain, and Portugal.[10][11]

During the British Iron Age, Cornwall, like all of Britain (modern England, Scotland, Wales, and the Isle of Man), was inhabited by a Celtic people known as the Britons with distinctive cultural relations to neighbouring Brittany. The Common Brittonic spoken at the time eventually developed into several distinct tongues, including Cornish, Welsh, Breton, Cumbric and Pictish.[12]

The first written account of Cornwall comes from the 1st-century BC Sicilian Greek historian Diodorus Siculus, supposedly quoting or paraphrasing the 4th-century BCE geographer Pytheas, who had sailed to Britain:

- The inhabitants of that part of Britain called Belerion (or Land's End) from their intercourse with foreign merchants, are civilised in their manner of life. They prepare the tin, working very carefully the earth in which it is produced ... Here then the merchants buy the tin from the natives and carry it over to Gaul, and after travelling overland for about thirty days, they finally bring their loads on horses to the mouth of the Rhône.[13]

The identity of these merchants is unknown. It has been theorised that they were Phoenicians, but there is no evidence for this.[14]

Professor Timothy Champion, discussing Diodorus Siculus's comments on the tin trade, states that "Diodorus never actually says that the Phoenicians sailed to Cornwall. In fact, he says quite the opposite: the production of Cornish tin was in the hands of the natives of Cornwall, and its transport to the Mediterranean was organised by local merchants, by sea and then over land through France, passing through areas well outside Phoenician control."[15]Isotopic evidence suggests that tin ingots found off the coast of Haifa, Israel, came from Cornwall.[16] Tin, required for the production of bronze, was a relatively rare and precious commodity in the Bronze Age – hence the interest shown in Devon and Cornwall's tin resources.

In the first four centuries CE, during the time of Roman dominance in Britain, Cornwall was rather remote from the main centres of Romanisation – the nearest being Isca Dumnoniorum, modern day Exeter. However, the Roman road-system extended into Cornwall with four significant Roman sites based on forts: Tregear near Nanstallon was discovered in the early 1970s, two others were found at Restormel Castle, Lostwithiel in 2007, and a third fort near Calstock was also discovered early in 2007. In addition, a Roman-style villa was found at Magor Farm, Illogan in 1935. However, after 410 CE, Cornwall appears to have reverted to rule by Romano-Celtic chieftains of the Cornovii tribe as part of the Brittonic kingdom of Dumnonia (which also included present-day Devonshire and the Scilly Isles), including the territory of one Marcus Cunomorus, with at least one significant power base at Tintagel in the early 6th century.

"King" Mark of Cornwall is a semi-historical figure known from Welsh literature, from the Matter of Britain, and, in particular, from the later Norman-Breton medieval romance of Tristan and Yseult, where he appears as a close relative of King Arthur, himself usually considered to be born of the Cornish people in folklore traditions derived from Geoffrey of Monmouth's 12th-century Historia Regum Britanniae.

Archaeology supports ecclesiastical, literary and legendary evidence for some relative economic stability and close cultural ties between the sub-Roman Westcountry, South Wales, Brittany, the Channel Islands, and Ireland through the fifth and sixth centuries.[17]

Economy

Tin mining was important in the Cornish economy from the High Middle Ages, and expanded greatly in the 19th century when rich copper mines were also in production. In the mid-19th century, tin and copper mines entered a period of decline and china clay extraction became more important. Mining had virtually ended by the 1990s. Fishing and agriculture were the other important sectors of the economy, but railways led to a growth of tourism in the 20th century after the decline of the mining and fishing industries.[18] Since the late 2010s there have been hopes of a resurgence of mining in Cornwall after the discovery of 'globally significant' deposits of lithium to help power the electric car revolution.[19]

Tourism

Cornwall is noted for its geology and coastal scenery. A large part of the Cornubian batholith is within Cornwall. The north coast has many cliffs where exposed geological formations are studied. The area is noted for its wild moorland landscapes, its long and varied coastline, its attractive villages, its many place-names derived from the Cornish language, and its very mild climate. Extensive stretches of Cornwall's coastline, and Bodmin Moor, are protected as an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty.[20]

Rural life

Quarried in Devon, Cornwall and Wales, slate has been used since 12th century. Its use increased dramatically during 18-19th century with the development of canals and railway; indeed in some areas it came close to entirely replacing thatch. Unbaked earth, often mixed with straw, is an ancient material. Employed walls of buildings, its use was wide spread in Britain until 19th century. These buildings keep cool in summer and warm in winter.The greatest construction of earth-built structures are in southwest, East Anglia and in parts of midlands. [21]

-

Rural Britain. St Ives, Cornwall, 1943, with men away in war, farmers wives milching cow, Courtesy - Rural Britain Then and Now, p.106

-

Rural Britain. StCleer Village. Liskeard, Cornwall, 1890, Courtesy - Rural Britain Then and Now, p.167

कॉर्नवल

कॉर्नवल दक्षिण पश्चिम इंग्लैंड में एक ऐतिहासिक काउंटी और औपचारिक काउंटी है। इसे सेल्टिक राष्ट्रों में से एक के रूप में मान्यता प्राप्त है, और यह कोर्निश लोगों की मातृभूमि है। कॉर्नवाल उत्तर और पश्चिम में अटलांटिक महासागर से, दक्षिण में इंग्लिश चैनल से, और पूर्व में डेवोन काउंटी द्वारा, तामार नदी के साथ उनके बीच की सीमा बनाती है। कॉर्नवाल ग्रेट ब्रिटेन द्वीप के दक्षिण पश्चिम प्रायद्वीप का सबसे पश्चिमी भाग है। दक्षिण-पश्चिमी बिंदु लैंड्स एंड और सबसे दक्षिणी छिपकली बिंदु है। कॉर्नवाल की जनसंख्या 568,210 है और इसका क्षेत्रफल 3,563 वर्ग किमी है। काउंटी को 2009 से एकात्मक प्राधिकरण, कॉर्नवाल काउंसिल द्वारा प्रशासित किया गया है। कॉर्नवाल की औपचारिक काउंटी में आइल्स ऑफ स्किली भी शामिल है, जिन्हें अलग से प्रशासित किया जाता है। कॉर्नवाल का प्रशासनिक केंद्र ट्रुरो है, जो इसका एकमात्र शहर है।

कॉर्नवाल पहले एक ब्रायथोनिक साम्राज्य था और बाद में एक शाही डची था। यह कोर्निश डायस्पोरा का सांस्कृतिक और जातीय मूल है। कोर्निश राष्ट्रवादी आंदोलन कॉर्नवाल की वर्तमान संवैधानिक स्थिति का विरोध करता है और वेल्स, स्कॉटलैंड और उत्तरी आयरलैंड के समान शक्तियों के साथ एक विधायी कोर्निश विधानसभा के रूप में यूनाइटेड किंगडम के भीतर अधिक स्वायत्तता चाहता है। कोर्निश लोगों को राष्ट्रीय अल्पसंख्यकों के संरक्षण के लिए यूरोपीय फ्रेमवर्क कन्वेंशन के तहत अल्पसंख्यक का दर्जा दिया गया था, उन्हें एक अलग जातीय समूह के रूप में मान्यता दी गई थी।

कॉर्नवाल में रोमन अवशेषों की हाल की खोजों से पता चलता है कि वहां रोमन उपस्थिति पहले से कहीं अधिक थी। रोमन साम्राज्य के पतन के बाद, कॉर्नवाल (डेवोन के साथ, डोरसेट और सॉमरसेट के कुछ हिस्सों, और स्किली आइल्स) ब्रिटोनिक साम्राज्य के ड्यूमोनिया का एक हिस्सा था, जो कॉर्नोवी के सरदारों द्वारा शासित था, जिसमें अर्ध के रूप में माने जाने वाले आंकड़े शामिल हो सकते थे। ऐतिहासिक या पौराणिक, जैसे कि किंग मार्क ऑफ कॉर्नवाल और किंग आर्थर, हिस्टोरिया रेगम ब्रिटानिया से प्राप्त लोककथाओं की परंपराओं से प्रमाणित हैं। 577 ईस्वी में देओरम की लड़ाई के बाद डुमोनी जनजाति के कॉर्नोवी डिवीजन को उनके साथी ब्रायथन ऑफ वेल्स से अलग कर दिया गया था, और अक्सर वेसेक्स के विस्तारित अंग्रेजी साम्राज्य के साथ संघर्ष में आया था। कॉर्नवाल (और डार्टमूर) के बाहर डुमनोनिया के क्षेत्रों को 838 ईस्वी तक अंग्रेजों ने अपने कब्जे में ले लिया था। 936 ईस्वी में राजा एथेलस्टन ने तामार नदी के पूर्वी तट के उच्च जल चिह्न पर अंग्रेजी और कोर्निश के बीच की सीमा निर्धारित की। प्रारंभिक मध्य युग से, भाषा और संस्कृति को चैनल के दोनों किनारों पर ब्रायथन व्यापार द्वारा साझा किया गया था, जिसके परिणामस्वरूप डोमोनी और कॉर्नौइल के संबंधित उच्च मध्ययुगीन ब्रेटन साम्राज्य और सेल्टिक ईसाई धर्म दोनों क्षेत्रों में आम थे।

उच्च मध्य युग से कोर्निश अर्थव्यवस्था में टिन खनन महत्वपूर्ण था, और 19 वीं शताब्दी में बहुत विस्तार हुआ जब समृद्ध तांबे की खदानें भी उत्पादन में थीं। 19वीं शताब्दी के मध्य में, टिन और तांबे की खदानों ने गिरावट की अवधि में प्रवेश किया और चीनी मिट्टी की निकासी अधिक महत्वपूर्ण हो गई। 1990 के दशक तक खनन लगभग समाप्त हो गया था। मत्स्य पालन और कृषि अर्थव्यवस्था के अन्य महत्वपूर्ण क्षेत्र थे, लेकिन रेलवे ने खनन और मछली पकड़ने के उद्योगों के पतन के बाद 20वीं शताब्दी में पर्यटन का विकास किया। 2010 के उत्तरार्ध से, इलेक्ट्रिक कार क्रांति को शक्ति प्रदान करने में मदद करने के लिए लिथियम के 'विश्व स्तर पर महत्वपूर्ण' जमा की खोज के बाद कॉर्नवाल में खनन के पुनरुत्थान की उम्मीद की जा रही है।

कॉर्नवाल अपने भूविज्ञान और तटीय दृश्यों के लिए विख्यात है। कॉर्नुबियन बाथोलिथ का एक बड़ा हिस्सा कॉर्नवाल के भीतर है। उत्तरी तट में कई चट्टानें हैं जहां उजागर भूवैज्ञानिक संरचनाओं का अध्ययन किया जाता है। यह क्षेत्र अपने जंगली दलदली परिदृश्य, इसकी लंबी और विविध तटरेखा, इसके आकर्षक गांवों, कोर्निश भाषा से प्राप्त इसके कई स्थान-नामों और इसकी बहुत ही हल्की जलवायु के लिए विख्यात है। कॉर्नवाल के समुद्र तट के व्यापक हिस्सों और बोडमिन मूर को उत्कृष्ट प्राकृतिक सौंदर्य के क्षेत्र के रूप में संरक्षित किया गया है।

Gallery

External links

References

- ↑ "Cornwall". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ↑ "Horn". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ↑ "Cornish History – Stone Age to Present Day". www.cornwalls.co.uk.

- ↑ "Blair gets Cornish assembly call". BBC News. 11 December 2001.

- ↑ "Cornish people granted minority status within UK". BBC

- ↑ ."Welsh and Cornish are the 'purest Britons', scientists claim". The Daily Telegraph

- ↑ "The Dumnonii". British Tribes. Roman-Britain.co.uk. 2011.

- ↑ Higham, Robert (2008). Making Anglo-Saxon Devon. Exeter: The Mint Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-903356-57-9.

- ↑ Stenton, F. M. (1947) Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Clarendon Press; p. 337

- ↑ Barry Cunliffe; John T. Koch, eds. (2010). Celtic from the West: Alternative Perspectives from Archaeology, Genetics, Language and Literature. Oxbow Books and Celtic Studies Publications. p. 384. ISBN 978-1-84217-410-4.

- ↑ Cunliffe, Barry (2009). "A Race Apart: Insularity and Connectivity". Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society. The Prehistoric Society. 75: 55–64. doi:10.1017/S0079497X00000293. S2CID 192963510.

- ↑ Payton, Philip (1996). Cornwall. Fowey: Alexander Associates. ISBN 1-899526-60-9.p.40

- ↑ Halliday, Frank Ernest (1959). A History of Cornwall. London: Gerald Duckworth. ISBN 0-7551-0817-5. p. 51.

- ↑ Halliday, Frank Ernest (1959). A History of Cornwall. London: Gerald Duckworth. ISBN 0-7551-0817-5. p. 52.

- ↑ Champion, Timothy (2001). "The appropriation of the Phoenicians in British imperial ideology". Nations and Nationalism. 7 (4): 451–65. doi:10.1111/1469-8219.00027.

- ↑ Woodyatt, Amy (19 September 2019). "Ancient tin found in Israel has unexpected Cornish links". CNN. Archived from the original on 9 January 2020.

- ↑ "AD 500 – Tintagel". Archaeology.co.uk. 24 May 2007.

- ↑ "How Cornwall's economy is fighting back". BBC News. 30 July 2006.

- ↑ Jack, Simon (11 June 2021). "Can mining save Cornwall's economy?". BBC News.

- ↑ "The Cornwall Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty". The Cornwall Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty.

- ↑ Rural Britain Then and Now : A Celebration of the British Countryside Featuring Photographs from the Francis Frith Collection by Roger Hunt, Forward by Sir Simon Jenkins, 2009, by Bounty Books, isbn:978-0-753719-53-4,pp.38-39