Prithivishena II

| Author:Laxman Burdak, IFS (R) |

Prithivishena II (470-490) was a ruler of the Nandivardhana-Pravarapura branch of the Vakataka dynasty. He succeeded his father Narendrasena as Maharaja. Prithivishena II is the last known king of the main Vakataka line, which is no longer attested after his reign.

Variants

Early life

Prithivishena was born to Narendrasena and his wife Ajjhitabhattarika, a princess of Kuntala.[2] He was probably born while his father was still a Crown Prince during the reign of Pravarasena II, Prithivishena's grandfather. A.S. Altekar suggests that when Prithivishena was a youth of about 20 years, he aided his father in repulsing the Nalas of the Bastar region who had invaded the Vakataka kingdom.[3]

Reign

Prithivishena's inscriptions refer to him twice rescuing the "sunken fortunes of his family".[4] It is unclear what these two instances were. Altekar suggests that the first instance was the aforementioned repulsion of the Nalas during the reign of Prithivishena's father, and the second instance relates to a war with the aggressive Traikutaka king Dahrasena, who is known to have performed an ashwamedha horse sacrifice and whose growing kingdom bordered the Vakataka realm on the west.[5] D.C. Sircar agrees with Altekar that an invasion by the Nalas constituted the first instance when Prithivishena had to retrieve the family's fortunes, and suggests that the second instance relates to a conflict with Harishena of the Vatsagulma branch of the Vakataka dynasty.[6]Notably, the seals on Prithivishena's charters reveal a more militant character than that of his predecessors, as they indicate that the king was "desirous of conquering".[7] However, we have no details of any of the wars which might have involved Prithivishena.

Prithivishena was a Vaishnavite who was described as a Parama-bhagavata or devout worshipper of Bhagavat (i.e. Vishnu).[8] This represented a reversion from the avowed Shaivism of his illustrious grandfather Pravarasena II. Prithivishena might have been inspired by the Vaishnavite faith of his great-grandmother Prabhavatigupta, because just like his great-grandmother Prithivishena issued his first public charter from the Vaishnavite religious sanctuary of Ramagiri.[9]

Successors

Prithivishena had no known successors from his own line, which seems to come to an end following his death. It is possible that Harishena of the Vatsagulma branch took over the leadership of the Vakataka family after Prithivishena's death. An inscription at Ajanta describes Harishena as the conqueror of many countries including Kuntala, Avanti, Lata, Koshala, Kalinga, and Andhra, and it is unlikely that Harishena could have extended his influence so widely without first securing the possession of some territories of the main Vakataka branch.[10]

There also exists abundant evidence that the Vishnukundins had a significant presence in parts of Vidarbha following the reign of Prithivishena. A hoard of loose coins found at Paunar in the Wardha district contain some coins which can be assigned to the reign of Prithivishena II, but a majority of them seem to be struck by the Vishnukundins.[11] Vishnukundin coins have also been found at Vakataka sites in the Gondia district. On the basis of this evidence, Ajay Mitra Shastri believes that the Vishnukundin king Madhavavarman II Janashraya, who is known to have married a Vakataka princess, took control of a large portion of the former Vakataka kingdom and extended his conquests as far as the Narmada River immediately after the death of Prithivishena.[12] Hans Bakker has a similar view and holds that Prithivishena had to accept a significant Vishnukundin presence in his realm to resist the Nalas, and those Vishnukundins became politically dominant over parts of the erstwhile Vakataka kingdom following Prithivishena's death.[13]

External links

See also

References

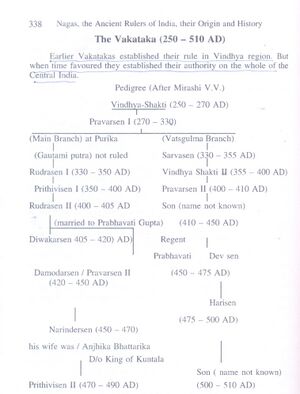

- ↑ Dr Naval Viyogi: Nagas – The Ancient Rulers of India/General Index of Nagas, The Ancient Rulers of India, p.338

- ↑ D.C. Sircar (1997). Majumdar, R.C. (ed.). The Classical Age (Fifth ed.). Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. p. 184.

- ↑ A.S. Altekar (2007). Majumdar, R.C.; Altekar, A.S. (eds.). The Vakataka-Gupta Age. Motilal Banarsi Dass. p. 110. ISBN 9788120800434.

- ↑ Singh, Upinder (2016). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson India Education Services. p. 483. ISBN 9788131716779.

- ↑ A.S. Altekar (2007). Majumdar, R.C.; Altekar, A.S. (eds.). The Vakataka-Gupta Age. Motilal Banarsi Dass. p. 110. ISBN 9788120800434.

- ↑ D.C. Sircar (1997). Majumdar, R.C. (ed.). The Classical Age (Fifth ed.). Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. p. 184.

- ↑ Bakker, Hans (1997). The Vakatakas: An Essay in Hindu Iconology. Groningen: Egbert Forsten. p. 51. ISBN 9069801000.

- ↑ D.C. Sircar (1997). Majumdar, R.C. (ed.). The Classical Age (Fifth ed.). Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. p. 184.

- ↑ Bakker, Hans (1997). The Vakatakas: An Essay in Hindu Iconology. Groningen: Egbert Forsten. p. 51. ISBN 9069801000.

- ↑ A.S. Altekar (2007). Majumdar, R.C.; Altekar, A.S. (eds.). The Vakataka-Gupta Age. Motilal Banarsi Dass. p. 110. ISBN 9788120800434.

- ↑ Bakker (1997), p. 56

- ↑ Shastri, Ajay Mitra (1987). Early History of the Deccan: Problems and Perspectives. New Delhi, India: Sundeep Prakashan. pp. 132–137. ISBN 9788185067063.

- ↑ Bakker (1997), p. 56