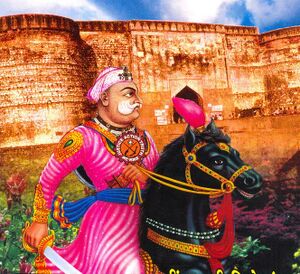

Maharaja Surajmal ruled in an age of treachery

- An article by Ahmed Ali published in Times of India Delhi, 16 August 1981. It is being reproduced here for research and study purpose.

Introduction

Raja Suraj Mal knew how to play his cards well, and seldom engaged in a war of conquest. He won almost all his battles, with the least loss of men, money and material. Even as a warrior, he remained a diplomat and was the epitome of honesty in an age beset with intrigues.

One of the three most outstanding personalities of 18th century India

Suraj Mal is one of the three most outstanding personalities of 18th century India, the other two being Ahmad Shah Abdali and Najib-ud-Daula the Rohilla Chieftain, who played a decisive role in those disturbed days. It is a curious fact that while much is known about the two Afghan statesmen, hardly anything has been written about Sura] Mal the great Jat who was not only their compeer in courage and valour, but superior to them in political insight and acumen.

In an age when survival depended on treachery, utter disregard of moral scruples, and when chivalry often assumed the guise of chicanery, he stood out as an exemplar of honour and loyalty. The publication, therefore, of a biography of this remarkable man by K. Natwar Singh, even though so long after his death, should be welcomed by all students of history.

Thus, on the death of Aurangzeb, with Rajput strength dissipated, central authority as good as extinct, the Maratha hordes pressed from the South, and Afghan adventurers like Nadir Shah and Ahmad Shah Abdali from the North, and the Jats and highway robbers roamed the countryside, and small boorish armies clashed day and night. The dwellers equally of cities, towns and villages were thrown at the mercy of vandals and robber barons. Not even the person of the Mughal king or his harem were immune. The British merchant adventurers found the opportunity of maneuvering for power and establishing their hold. In spite of the loyalty of strong indigenous groups, Nadir Shah and, following him, Ahmad Shah Abdali , destroyed even the pretense of Mughal paramountcy.

It is in this context that Suraj Mal's role is to be viewed as a statesman, diplomat and man of vision. He seemed to have a grand design of a confederacy of various Indian States under a Mughal (or Turani) emperor with an able chief minister from the Irani Umera or nobles who would not be too ambitious. That his vision was far-sighted is proved by the fact that the name and person of the "pensioner" King of Delhi was still the symbol of power and unity, and had to be invoked in 1857 when the Indian "sepoys" rose against the East India Company and were joined by a number of spirited descendants of Maratha, Rajput, Rohilla and Irani nobles and princes. It is worth speculating if the British had not been there, would the scenario of India have been very different from the dream of this great unlettered Jat, Raja Suraj Mal?

Suraj Mal possessed great wisdom

An illiterate man, Suraj Mal possessed great wisdom sharpened by experience. A member of the Jat clan, he rose to power by sheer dint of personal effort and native genius. His forebears were sturdy peasants, who cultivated their lands, built durable mud fortresses, though by preference they were highway robbers. They were a Central Asian people, though Natwar Singh refrains from discussing their controversial origins traced by some to Aryans and to Scythians by some others. The consistent pattern of their behaviour, and clan characteristics based in racial instincts, however, point to the Huns, a nomadic Central Asian warlike race, a branch of which went to Europe in the 4th century A.D. where they are also known by the name of Vandals. The branch that came to India, between the 4th and 6th centuries, was called the White Huns, who spread from the bank of the Indus, through the Punjab, Northern Rajasthan, the Upper Jamuna Valley down to Gwalior beyond the Chambal, Gujars and Ahirs are also of the same race.

Apart from agricultural pursuits, they lived by looting caravans: and finding the area between Delhi and Agra rich in these opportunities they made it their favourite hunting ground, and earned the nickname of bad-zat, villains. Being essentially pagan they did not have any deep religious feeling, and though the majority chose the Hindu denomination, many became Muslim and many of them turned Sikh. A small clan of theirs numbering three or four thousand also settled in Iraq, going from India, where they are known as Zat.

Birth Of A Kingdom

Descended from these people, Suraj Mal turned his attention to consolidating his position as a chieftain and a statesman, for which he had a natural disposition. He expanded his area and principality into a kingdom, turning every peril into a stepping stone for greater wealth and greater glory. His remarkable sense and grasp of the realities of life led him to avoid unnecessary risks; and he came out of every dangerous situation unscathed when other and more powerful chiefs and generals could not escape unhurt. His accidental death in the hour of his triumph brings to mind the warning he gave to Ahmad Shah that while mortals could start a conflict the end rested finally with God.

Viewed in the context of the Indian situation in the middle d the 18th century, the mantle of statesmanship was thrust upon Suraj Mal's shoulders which were broad enough to wear it with ease.

In that age of shifting loyalties when no oath sworn on the Quran or the holy water of the Ganges was held sacred, Suraj Mal gave proof of great chivalry by offering shelter to Imad-ul-Mulk, his inveterate enemy. Similarly, when the Marathas were utterly defeated by Ahmad Shah Abdali at Panipat, they found refuge in the do-main of Suraj Mal even though on the eve of battle they had made him a virtual prisoner. And when Safdar Jang was at the mercy of the Turki (or Mughal) Umera, Suraj Mal not only refused to join, forces against him, but he made the emperor restore the viceroyalty of Allahabad and Oudh to him, thus paving the way for the founding of the last haven of Indo-Muslim Culture in Lucknow by Safdar Jang's son Shuja-ud-Daula in those days of Delhi's twilight and decay.

Suraj Mal indeed knew how to play his cards well, and seldom engaged in a war of conquest Until after the Third Battle of Panipat. He won almost all his battles with the least loss of men, money and material. Even after the last battle when he lost his life. his army retired in good order, so that Najib-ud-Daula, his adversary, did not believe that Suraj Mal had really been killed, and is credited with the well-known saying:

- "Take the Jat to be dead when the thirteenth day ceremony of his burial has been performed."

Yet he took no avoidable risk, and whenever he saw an opportunity of self-aggrandisement, or when his honour was at stake, he himself took the field; and it was when he found a power vacuum after the defeat of the Marathas that he expanded his territory by conquering other lands until his domain extended to East Punjab and Western U.P., and he ruled an area approximately two hundred by one hundred miles.

A warrior diplomat

Even as a warrior he remained a diplomat; and the advice he gave the chief of Maratha armies was to adopt guerrilla tactics and desist from fighting a regular war. He had no peer in diplomacy among. the Indian chieftains whether Maratha, Rohillas or Rajputs. Even the redoubtoh Abdali was outwitted by him, for he knew the mettle of the adversary and did not challenge him or force the issue. His correspondence with Ahmad Shah is one of the most stirring examples of this art, and shows his shrewdness.

Courage and valour were the hallmarks of the leaders in those turbulent times, whether Ahmad Shah, Najib-ud-Daula or Sadashiv Bhao. In many ways, however, Suraj Mal excelled his contemporaries, and in prudence foremost. Whatever he may or may not have done, he never wanted to destroy the Mughal House which he recognised as the sign and symbol of Indian unity. He had no sympathy with the Marathas whose concept or government did not appeal to him. In the final assessment, he was one of the most Impressive personalities an age could produce. It is fortunate that his biography has been written by Natwar Singh who is eminently qualified for the task. He is a well-known writer, scholar, editor and an experienced diplomat. More than all, he is a descendant of Raja Suraj Mal and a scion of the Bharatpur ruling family and married to the Princess of Patiala. Writing about one's forebear after more than two hundred years of his deah can not by any means be easy. Yet he has succeeded singularly in presenting a graphic study of the time in which Sura] Mal lived, highlighting his achievements against the background of political turmoil, chaos and decay.

Writing of a period identified with the Mughals, even though lit marks the beginning of the end of the Muslim phase of Indian history as contrived by the imperialist imagination of the British and the machinations of Western orientalists, is fraught with many difficulties, especially now and in these days of shattered tradition, class and communal hatred and prejudice, heritage of torn identied, "generalised moral mush." But ties and, what Arthur Miller call the restraint which Natwar Singh shows in his approach is both admirable and remarkable.

Nonetheless, a few slurrings-over and misreadings of facts and realities have crept into his otherwise objective study. There is, for instance, his generalisation: "There is no doubt that the impact Muslim culture made on the Hindus has been profound and lasting. Nowhere is this more true than of the regions inhabited by the Jats. Sartorially, gastronomically and linguistically Islam enriched Indian life. But that was all. Inter-religious marriages were very rare and no Hindu studied the Koran and no Muslim the Gita. They co-existed in water-tight compartments.”

Jarring Note

Coming from the pen of a writer of such wide culture has written the history of cult period admirably, this like a jarring note. It may perhaps be due to his lack of knowledge of the Urdu script, the real language of l8th century India in which this grief-torn mother-goddess expressed her heart openly. If he had read the works Taqi Mir and Nazir, and even otherwise he would have known how the age-was suffused with the spirit of the Bhakti movement and that no distinctions were made even perhaps existed, between Hindu and Muslim. And if allowed his vision to penetrate courtyards of the palace at Delhi or let it roam over the streets and surrounding areas of the city of Shahjehanabad, he would have seen a different picture of celebrations of Hindu and Muslim festivals, and how people vied to make one another rakhi-band bhai brothers joined in Hindu religious ecstasy. He would have seen this spirit pervade the court of Muhammad Shah, whose dohas and love of music were steeped in it. And only a few decades beyond this the life and preoccupations of Dara Shikoh with mysticism and study of Vedas and Gita and Hindu scriptures, stand as clear testimony to this living reality, as the example of Akbar a little earlier still.

Not only in what our author enumerates, but in habits, customs, attitudes, art and architecture, social life and thought, and in the crystallisation of the Hindu religion itself, the hand of Islamic culture is visible everywhere through the length and breadth of India. We are, alas, today the dupes of the British policy of divide and rule! As for inter-religious marriages, the rigid Hindu caste-system stood as a sadd-i-Sikandari [[Sura] Ma]] spoke of, the very Wall of China, in the way of even intercaste marriages. And yet look at the lives of many a Muslim king and noble whose very blood is mixed with the Hindu.

How many such marriages have gone unnoticed and unrecorded, for they were a common occurrence, shall never be known. The water-tight compartmentation Natwar Singh complains of was the result of Hindu or Brahmanical Orthodoxy with its barrier of touchability and untouchability.

It is tragic that a European power, taking advantage of the stark ignorance of the multitudes inhabiting the vast land of India, then in the throes of civil strife yet thirsting for peace and order, subjugated the land, and distorted and rewrote the History of India dividing it into an arbitrary division of Hindu, Muslim and British periods.

And so have the British historians presented the Battle of Panipat as a fight between Muslims and Hindus, which it is doubtful if it ever was, yet which paved the way for the British conquest of India with (he help of Indians themselves who were all ignorant as these historians of the reality or of sociology. The times were torn and out of joint, so that chivalry lay frayed to shreds in dust, and Najib-ud-Daula had to turn against his dharampita Malhar Rao when he realised that without the help of Abdali he would be left completely at the mercy of the Jats or Marathas. Shuja-ud-Daula, the emissary of Peshwa's commander, who dreaded both the Rohilla and the Holkar, had to choose half-heartedly to side with Abdali realising that he had a better chance of victory, And this was also the line of reasoning which prompted Suraj Mal himself to refrain from coming to the aid of his powerful "co-religionists", and to remain neutral in this sad and modern Mahabharat where the main actors lost the field to a foreign enemy lying in ambush.

External links

References

- Maharaja Suraj Mal : By K.Natwar Singh, George Allen & Unwin, London

Back to Jat History