Mylasa

| Author:Laxman Burdak, IFS (R) |

Mylasa (Ancient Greek: Μύλασα) was an ancient Anatolian city and the seat of the district of the same name. Its present name is Milas situated in Muğla Province in southwestern Turkey.

Variants

- Mylasa (Anabasis by Arrian, p.59, 61.)

- Mylasa (Ancient Greek: Μύλασα)

- Milas

Jat Gotras Namesake

- Myla = Mylasa (Anabasis by Arrian, p.59, 61.)

Etymology

The name Mylasa, with the old Anatolian ending in -asa is evidence of very early foundation. On the basis of the -mil syllable found also in the name the Lycians called themselves Trmili, a theory connects the name of Mylasa with the passage of the Lycians from Miletus, also claimed to be a Lycian foundation under the name Millawanda by Ephorus, to their final home in the south. But there is nothing else to suggest a Lycian origin for the name Mylasa.[1]

Stephanus of Byzantium in his Ethnica says that the city took its name from a certain Mylasus, son of Chrysaor and a descendant of Sisyphus and Aeolus, an explanation some sources deem unsubstantial for a Carian city.[2]

Geography

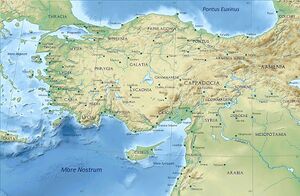

The city commands a region with an active economy and is very rich in history and ancient remains, the territory of Milas containing a remarkable twenty-seven archaeological sites of note. Some of these are (with the names of modern-day settlements indicated in cases where ancient sites are found right within these; Beçin, Chalcetor, Euromus -originally Kyromus-, Heracleia by Latmus (Kapıkırı), Hydae -originally Kydae- (Damlıboğaz), Iasos (Kıyıkışlacık), Keramos/Ceramus (Ören), Kuyruklu Kale (Yusufça), Labranda, Olymus -originally Hylimus-.

The city was the first capital of ancient Caria and of the Anatolian beylik of Menteşe in mediaeval times. The nearby Mausoleum of Hecatomnus is classified as a tentative UNESCO World Heritage Site.[3]

Milas district covers a total area of 2167 km2 and this area follows a total coastline length of 150 km, both to the north-west in the Gulf of Güllük and to the south along the Gulf of Gökova, and to these should be added the shores of Lake Bafa in the north divided between the district area of Milas and that of Aydın district of Söke.

Along with the province seat of Muğla and the province's southernmost district of Fethiye, Milas is among the prominent settlements of south-west Turkey, these three centers being on a par with each other in terms of all-year population and the area their depending districts cover. Five townships have their own municipalities, and a total of 114 villages depend on Milas, distinguishing the district with a record number of dependent settlements for a very wide surrounding region. Milas center is situated on a fertile plain at the foot of Mount Sodra, on and around which sizable quarries of white marble are found and have been used since very ancient times.

History

The city's earliest historical mention is at the beginning of the 7th century BC, when a Carian leader from Mylasa by name Arselis is recorded to have helped Gyges of Lydia in his contest for the Lydian throne. The same episode is at the origin of the accounts surrounding the beginning of the cult for and the erection of the statue of Labrandean Zeus in the neighboring sanctuary of Labranda, held sacred by peoples across western Anatolia, with the statue holding the labrys brought over by Arselis from Lydia. Labrandean Zeus (sometimes also named "Zeus Stratios") was one of the three deities proper to Mylasa, all named Zeus but each bearing indigenous characteristics. Of these, the cult of Zeus Carius (Carian Zeus) was also notable in being exclusively reserved, aside from the Carians, to their [Lydian]] and Mysian kinsmen. One of the finest temples was also the one dedicated to Zeus Osogoa (originally, just Osogoa), traceable to times when the Carians had been a maritime folk and which recalled to Pausanias the Acropolis of Athens.

Ch. 20 Siege of Halicarnassus.— Abortive Attack on Myndus (p.58-61)

Arrian [4] mentions..... Alexander now resolved to disband his fleet, partly from lack of money at the time, and partly because he saw that his own fleet was not a match in battle for that of the Persians. On this account he was unwilling to run the risk of losing even a part of his armament. Besides, he considered, that now he was occupying Asia with his land force, he would no longer be in need of a fleet; and that he would be able to break up that of the Persians, if he captured the maritime cities; since they would neither have any ports from which they could recruit their crews, nor any harbour in Asia to which they could bring their ships. Thus he explained the omen of the eagle to signify that he should get the mastery over the enemy's ships by his land force. After doing this, he set forth into Caria,[1] because it was reported that a considerable force, both of foreigners and of Grecian auxiliaries, had collected in Halicarnassus.[2] Having taken all the cities between Miletus and Halicarnassus as soon as he approached them, he encamped near the latter city, at a distance from it of about five stades,[3] as if he expected a long siege. For the natural position of the place made it strong; and wherever there seemed to be any deficiency in security, it had been entirely supplied long before by Memnon, who was there in person, having now been proclaimed by Darius governor of lower Asia and commander of the entire fleet. Many Grecian mercenary soldiers had been left in the city, as well as many Persian troops; the triremes also were moored in the harbour, so that the sailors might reader him valuable aid in the operations. On the first day of the siege, while Alexander was leading his men up to the wall in the direction of the gate leading towards Mylasa,[4] the men in the city made a sortie, and a skirmish took place; but Alexander's men making a rush upon them repulsed them with ease, and shut them up in the city. A few days after this, the king took the shield-bearing guards, the Cavalry Companions, the infantry regiments of Amyntas, Perdiccas and Meleager, and in addition to these the archers and Agrianians, and went round to the part of the city which is in the direction of Myndus, both for the purpose of inspecting the wall, to see if it happened to be more easy to be assaulted there than elsewhere; and at the same time to see if he could get hold of Myndus[5] by a sudden and secret attack. For he thought that if Myndus were his own, it would be no small help in the siege of Halicarnassus; moreover an offer to surrender had been made by the Myndians if he would approach the town secretly, under the cover of night. About midnight, therefore, he approached the wall, according to the plan agreed on; but as no sign of surrender was made by the men within, and though he had with him no military engines or ladders, inasmuch as he had not set out to besiege the town, but to receive it on surrender, he nevertheless led the Macedonian phalanx near and ordered them to undermine the wall. They threw down one of the towers, which, however, in its fall did not make a breach in the wall. But the men in the city stoutly defending themselves, and at the same time many from Halicarnassus having already come to their aid by sea, made it impossible for Alexander to capture Myndus by surprise or sudden assault. Wherefore he returned without accomplishing any of the plans for which he had set out, and devoted himself once more to the siege of Halicarnassus.

In the first place he filled up with earth the ditch which the enemy had dug in front of the city, about thirty cubits wide and fifteen deep; so that it might be easy to bring forward the towers, from which he intended to discharge missiles against the defenders of the wall; and that he might bring up the other engines with which he was planning to batter the wall down. He easily filled up the ditch, and the towers were then brought forward. But the men in Halicarnassus made a sally by night with the design of setting fire both to the towers and the other engines which had been brought up to the wall, or were nearly brought up to it. They were, however, easily repelled and shut up again within the walls by the Macedonians who were guarding the engines, and by others who were aroused by the noise of the struggle and who came to their aid. Neoptolemus, the brother of Arrhabaeus, son of Amyntas, one of those who had deserted to Darius, was killed, with about 170 others of the enemy. Of Alexander's soldiers sixteen were killed and 300 wounded; for the sally being made in the night, they were less able to guard themselves from being wounded.

1. Caria formed the south-west angle of Asia Minor. The Greeks asserted that the Carians were emigrants from Crete. We learn from Thucydides and Herodotus that they entered the service of foreign rulers. They formed the body-guard of queen Athaliah, who had usurped the throne and stood in need of foreign mercenaries. The word translated in our Bible in 2 Kings xi. 4, 19 as captains, ought to be rendered Carians. See Fuerst's Hebrew Lexicon, sub voce בׇּרֳי.

2. Now called Budrum. It was the birthplace of the historians Herodotus and Dionysius.

2. Little more than half a mile.

4. Now called Melasso, a city of Caria, about ten miles from the Gulf of Iassus.

5. A colony of Troezen, on the western extremity of the same peninsula on which stood Halicarnassus.

External links

References

- ↑ Antony G. Keen (1998). Dynastic Lycia: A political history of the Lycians and their relations with foreign powers, C. 545-362. Brill Publishers, Leiden. ISBN 978-90-04-10956-8.

- ↑ George Ewart Bean (1989). Turkey beyond the Meander. John Murray Publishers Ltd, London. ISBN 978-0-7195-4663-1.

- ↑ Mausoleum and Sacred area of Hecatomnus: https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/5729/

- ↑ The Anabasis of Alexander/1b,pp.58-61

Back to Jat Places