Sami peoples

| Author:Laxman Burdak, IFS (R) |

Sami peoples or Screrefennae were a Germanic tribe living in Scandza (Scandinavia) mentioned by historian Jordanes in his work Getica. Screrefennae (i.e. Sami peoples) lived as hunter-gatherers living on a multitude of game in the swamps and on birds' eggs.

Variants

Jat clans

History

Sámi (/ˈsɑːmi/ SAH-mee; also spelled Sami or Saami) are a Finno-Ugric-speaking people inhabiting the region of Sápmi (formerly known as Lapland), which today encompasses large northern parts of Norway, Sweden, Finland, and of the Murmansk Oblast, Russia, most of the Kola Peninsula in particular. The Sámi have historically been known in English as Lapps or Laplanders, but these terms are regarded as offensive by the Sámi, who prefer the area's name in their own languages, e.g. Northern Sámi Sápmi.[1][2] Their traditional languages are the Sámi languages, which are classified as a branch of the Uralic language family.

Traditionally, the Sámi have pursued a variety of livelihoods, including coastal fishing, fur trapping, and sheep herding. Their best-known means of livelihood is semi-nomadic reindeer herding. Currently about 10% of the Sámi are connected to reindeer herding, which provides them with meat, fur, and transportation. 2,800 Sámi people are actively involved in reindeer herding on a full-time basis in Norway.[3] For traditional, environmental, cultural, and political reasons, reindeer herding is legally reserved for only Sámi in some regions of the Nordic countries.[4]

Etymologies

Speakers of Northern Sámi refer to themselves as Sámit (the Sámis) or Sápmelaš (of Sámi kin), the word Sápmi being inflected into various grammatical forms. Other Sámi languages use cognate words. As of around 2014, the current consensus among specialists was that the word Sámi was borrowed from the Proto-Baltic word *žēmē, meaning 'land' (cognate with Slavic zemlja (земля), of the same meaning).[5][6][7]

The word Sámi has at least one cognate word in Finnish: Proto-Baltic *žēmē was also borrowed into Proto-Finnic, as *šämä. This word became modern Finnish Häme (Finnish for the region of Tavastia; the second ä of *šämä is still found in the adjective Hämäläinen). The Finnish word for Finland, Suomi, is also thought probably to derive ultimately from Proto-Baltic *žēmē, though the precise route is debated and proposals usually involve complex processes of borrowing and reborrowing. Suomi and its adjectival form suomalainen must come from *sōme-/sōma-. In one proposal, this Finnish word comes from a Proto-Germanic word *sōma-, itself from Proto-Baltic *sāma-, in turn borrowed from Proto-Finnic *šämä, which was borrowed from *žēmē.[12]

The Sámi institutions—notably the parliaments, radio and TV stations, theatres, etc.—all use the term Sámi, including when addressing outsiders in Norwegian, Swedish, Finnish, or English. In Norwegian and Swedish, the Sámi are today referred to by the localized form Same.

The first probable historical mention of the Sámi, naming them Fenni, was by Tacitus, about AD 98.[8] Variants of Finn or Fenni were in wide use in ancient times, judging from the names Fenni and Φίννοι (Phinnoi) in classical Roman and Greek works. Finn (or variants, such as skridfinn, 'striding Finn') was the name originally used by Norse speakers (and their proto-Norse speaking ancestors) to refer to the Sámi, as attested in the Icelandic Eddas and Norse sagas (11th to 14th centuries).

The etymology is somewhat uncertain,[9] but the consensus seems to be that it is related to Old Norse finna, from proto-Germanic *finþanan ('to find'), the logic being that the Sámi, as hunter-gatherers "found" their food, rather than grew it.[10][11] This etymology has superseded older speculations that the word might be related to fen.[12]

As Old Norse gradually developed into the separate Scandinavian languages, Swedes apparently took to using Finn to refer to inhabitants of what is now Finland, while the Sámi came to be called Lapps. In Norway, however, Sámi were still called Finns at least until the modern era (reflected in toponyms like Finnmark, Finnsnes, Finnfjord and Finnøy), and some northern Norwegians will still occasionally use Finn to refer to Sámi people, although the Sámi themselves now consider this to be an inappropriate term. Finnish immigrants to Northern Norway in the 18th and 19th centuries were referred to as Kvens to distinguish them from the Sámi "Finns". Ethnic Finns (suomalaiset) are a distinct group from Sámi.[13]

The word Lapp can be traced to Old Swedish lapper, Icelandic lappir (plural) perhaps of Finnish origin;[14] compare Finnish lappalainen "Lapp", Lappi "Lapland" (possibly meaning "wilderness in the north"), the original meaning being unknown.[15][16] It is unknown how the word Lapp came into the Norse language, but one of the first written mentions of the term is in the Gesta Danorum by the twelfth-century Danish historian Saxo Grammaticus, who referred to 'the two Lappias', although he still referred to the Sámi as (Skrid-)Finns.[17][18] In fact, Saxo never explicitly connects the Sámi with the "two Laplands". The term "Lapp" was popularized and became the standard terminology by the work of Johannes Schefferus, Acta Lapponica (1673).

The Sámi are often known in other languages by the exonyms Lap, Lapp, or Laplanders, although these are considered derogatory terms,[19]while others accept at least the name Lappland.[20]Variants of the name Lapp were originally used in Sweden and Finland and, through Swedish, adopted by many major European languages: English: Lapps; German, Dutch: Lappen; French: Lapons; Greek: Λάπωνες (Lápōnes); Hungarian: lappok; Italian: Lapponi; Polish: Lapończycy; Portuguese: Lapões; Spanish: Lapones; Romanian: laponi; Turkish: Lapon. In Russian the corresponding term is лопари́ (lopari) and in Ukrainian лопарі́ (lopari).

In Finland and Sweden, Lapp is common in place names, such as Lappi (Satakunta), Lappeenranta (South Karelia) and Lapinlahti (North Savo) in Finland; and Lapp (Stockholm County), Lappe (Södermanland) and Lappabo (Småland) in Sweden. As already mentioned, Finn is a common element in Norwegian (particularly Northern Norwegian) place names, whereas Lapp is exceedingly rare.

Terminological issues in Finnish are somewhat different. Finns living in Finnish Lapland generally call themselves lappilainen, whereas the similar word for the Sámi people is lappalainen. This can be confusing for foreign visitors because of the similar lives Finns and Sámi people live today in Lapland. Lappalainen is also a common family name in Finland. In Finnish, saamelainen is the most commonly used word nowadays, especially in official contexts.

Inhabitants of Scandza

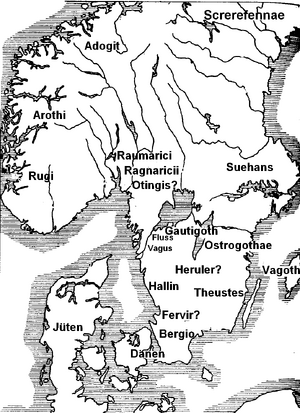

Jordanes names a multitude of tribes living in Scandza, which he named a womb of nations (loosely translated), and says they were taller and more ferocious than the Germans (archaeological evidence has shown the Scandinavians of the time were tall, probably due to their diet). This is a strong evidence that they were Jats. The listing represents several instances of the same people named twice, which was probably due to the gathering of information from diverse travellers[21] and from Scandinavians arriving to join the Goths, such as Rodwulf from Bohuslän.[22] Whereas linguists have been able to connect some names to regions in Scandinavia, there are others that may be based on misunderstandings.[23]

On the island there were the Screrefennae (i.e. Sami peoples[24]) who lived as hunter-gatherers living on a multitude of game in the swamps and on birds' eggs.

There were also the Suehans (Swedes) who had splendid horses like the Thuringians (Snorri Sturluson wrote that the 6th-century Swedish king Adils had the best horses of his time). They were the suppliers of black fox skins for the Roman market and they were richly dressed even though they lived in poverty.

There were also the Theustes (the people of the Tjust region in Småland), Vagoths (probably the Gutes of Gotland[25]), Bergio (either the people of Bjäre Hundred in Skåne, according to L Weibull, or the people of Kolmården according to others), Hallin (southern Halland) and the Liothida (either the Luggude Hundred or Lödde in Skåne, but others connect them to Södermanland[26]) who live in a flat and fertile region, due to which they are subject to the attacks of their neighbours.

Other tribes were the Ahelmil (identified with the region of Halmstad[27]), the Finnaithae (Finnhaith-, i.e. Finnheden, the old name for Finnveden), the Fervir (the inhabitants of Fjäre Hundred) and the Gautigoths (the Geats of Västergötland), a nation which was bold and quick to engage in war.

There were also the Mixi, Evagreotingis (or the Evagres and the Otingis depending on the translator), who live like animals among the rocks (probably the numerous hillforts and Evagreotingis is believed to have meant the "people of the island hill forts" which best fits the people of southern Bohuslän[28]).

Beyond them, there were the Ostrogoths (Östergötland), Raumarici (Romerike), the Ragnaricii (probably Ranrike, an old name for the northern part of Bohuslän) and the most gentle Finns (probably the second mention of the Sami peoples[29] mixed for no reason). The Vinoviloth (possibly remaining Lombards, vinili[30]) were similar.

He also named the Suetidi; a second mention of the Swedes[31][32] It can also be relevant to discuss if the term "Suetidi" could be equated with the term "Svitjod".[33] The Dani were of the same stock and drove the Heruls from their lands. Those tribes were the tallest of men.

In the same area there were the Granni (Grenland[34]), Augandzi (Agder[35]), Eunixi, Taetel, Rugii ([36]), Arochi ([37]) and Ranii (possibly the people of Romsdalen[38]). The king Rodulf was of the Ranii but left his kingdom and joined Theodoric, king of the Goths.

External links

See also

References

- ↑ Rapp, Ole Magnus; Stein, Catherine (8 February 2008). "Samis don't want to be 'Lapps'". Aftenposten

- ↑ Sternlund, Hans; Haupt, Inger (6 November 2017). "Ordet lapp var i fokus första rättegångsdagen" [The word lapp was in focus for the first day of the trial]. SVT Nyhetter Norrbotten (in Swedish). Norrbotten, Sweden.

- ↑ Solbakk, John T. "Reindeer husbandry – an exclusive Sámi livelihood in Norway" (PDF). www.galdu.org.

- ↑ Conrad, Jo Ann (Winter 2000). "Sami reindeer-herders today: Image or reality?". Scandinavian Review.

- ↑ Grünthal, Riho (29 February 2008). "The Finnic Ethnonyms". Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seura. Finno-Ugrian Society.

- ↑ Derksen, Rick (2007). Etymological Dictionary of the Slavic Inherited Lexicon. Leiden: Brill. p. 542.

- ↑ Hansen, Lars Ivar; Olsen, Bjørnar (2014). Hunters in Transition: An Outline of Early Sámi History. The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economics and Cultures. Vol. 63. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-25254-7. p.36

- ↑ Tacitus (1999) [c. 98 AD]. Rives, Archibald Black (ed.). Germania: Translated with Introduction and Commentary. Oxford University Press. pp. 96, 322, 326, 327. ISBN 978-0-19-815050-3.

- ↑ de Vries, Jan (1962). "Finnr.". Altnordisches etymologisches Wörterbuch [Old Norse Etymological Dictionary] (in German) (2nd ed.). Leiden: Brill Publishers. OCLC 685115.

- ↑ Grünthal, Riho (29 February 2008). "The Finnic Ethnonyms". Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seura. Finno-Ugrian Society.

- ↑ Collinder, Björn (1965). An Introduction to the Uralic Languages. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 8. ISBN 9780520329881.

- ↑ "Finn, n". OED Online.

- ↑ Laakso, Johanna, ed. (1992). Uralilaiset kansat: tietoa suomen sukukielistä ja niiden puhujista [Uralic peoples: information on Finnish mother tongues and their speakers] (in Finnish). Juva: WSOY. pp. 39–40.

- ↑ Hellquist, Elof (1922). Svensk etymologisk ordbok [Swedish Etymological Dictionary] (in Swedish). Lund: C. W. K. Gleerups förlag. p. 397.

- ↑ Hellquist, Elof (1922). Svensk etymologisk ordbok [Swedish Etymological Dictionary] (in Swedish). Lund: C. W. K. Gleerups förlag. p. 397.

- ↑ de Vries, Jan (1962). Altnordisches etymologisches Wörterbuch (in German). Leiden: Brill Publishers. pp. s.v. lappir. OCLC 555216596.

- ↑ Simms, Doug. "The Early Period of Sámi History, from the Beginnings to the 16th Century". Sami Culture. University of Texas at Austin.

- ↑ Grammaticus, Saxo. Killings, Douglas B. (ed.). The Danish History: Book Five, Part II. Translated by Elton, Oliver.

- ↑ Paine, Robert (1957). "Coast Lapp society". 4. Tromsø University Museum: 3.

- ↑ Rapp, Ole Magnus; Stein, Catherine (8 February 2008). "Sámis don't want to be 'Lapps'". Aftenposten.

- ↑ Nerman, B. Det svenska rikets uppkomst. Stockholm, 1925. p.46

- ↑ Ohlmarks, Å. (1994). Fornnordiskt lexikon, p.255

- ↑ Burenhult 1996:94

- ↑ Nerman 1925:36

- ↑ Nerman 1925:40

- ↑ Nerman 1925:38

- ↑ Ohlmarks 1994:10

- ↑ Nerman 1925:42ff

- ↑ Nerman 1925:44

- ↑ See Christie, Neil. The Lombards: The Ancient Longobards (The Peoples of Europe Series). ISBN 978-0-631-21197-6.

- ↑ Nerman 1925:44

- ↑ Thunberg, Carl L. (2012). Att tolka Svitjod. University of Gothenburg/CLTS. p. 44. ISBN 978-91-981859-4-2.

- ↑ Thunberg 2012:44-52.

- ↑ Nerman 1925:45

- ↑ Nerman 1925:45

- ↑ RogalandNerman 1925:45

- ↑ HordalandNerman 1925:45

- ↑ Nerman 1925:45