Sardinia

| Author: Laxman Burdak, IFS (R). |

Sardinia is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea (after Sicily and before Cyprus). It is located in the Western Mediterranean, to the immediate south of the French island of Corsica. Sardinia is politically a region of Italy.

Variants of name

- Sardinia (Anabasis by Arrian, p. 108.)

- Sardinia (Pliny.vi.39)

- Sardinian/Sardinians

- Sardegna (Italian: [sarˈdeɲɲa])

- Sardìgna/Sardìnnia (Sardinian: [sarˈdiɲɲa]/[sarˈdinja] )

- Sardhigna (Sassarese)

- Saldigna (Gallurese)

- Sardenya (Catalan)

- Sardegna (Tabarchino)

- Ichnusa (the Latinised form of Ancient Greek: Υκνούσσα)

Jat Gotras Namesake

- Sandal = Sardinia (Pliny.vi.39)

- Sardhi = Sardis (Σάρδεις) = Sardinia (Pliny.vi.39)

- Saradhi = Sardis (Σάρδεις) = Sardinia (Pliny.vi.39)

- Sardiya = Sardis (Σάρδεις) = Sardinia (Pliny.vi.39)

- Sardoo = Sardo (Σαρδώ) = Sardinia (Pliny.vi.39)

Jat Gotras Namesake

- Sandal = Sardinia (Anabasis by Arrian, p. 108.)

- Sardhi = Sardinia (Anabasis by Arrian, p. 108.)

- Saradhi = Sardinia (Anabasis by Arrian, p. 108.)

- Sardiya = Sardinia (Anabasis by Arrian, p. 108.)

Etymology

The name Sardinia is from the pre-Roman noun *s(a)rd-, later romanised as sardus (feminine sarda). It makes its first appearance on the Nora Stone, where the word Šrdn testifies to the name's existence when the Phoenician merchants first arrived.[1] According to Timaeus, one of Plato's dialogues, Sardinia and its people as well might have been named after Sardò (Σαρδώ), a legendary woman born in Sardis (Σάρδεις), capital of the ancient Kingdom of Lydia.[2][3] There has also been speculation that identifies the ancient Nuragic Sards with the Sherden, one of the Sea Peoples.[4][5] It is suggested that the name had a religious connotation from its use also as the adjective for the ancient Sardinian mythological hero-god Sardus Pater[6] "Sardinian Father" (in modern times misunderstood as being "Father Sardus"), as well as being the stem of the adjective "sardonic". In Classical antiquity, Sardinia was called Ichnusa (the Latinised form of Ancient Greek: Υκνούσσα), Σανδάλιον "Sandal", Sardinia and Sardó (Σαρδώ).

Location

It is divided into four provinces and a metropolitan city, with Cagliari being the region's capital and its largest city as well. Sardinia's indigenous language and the other minority languages (Sassarese, Corsican Gallurese, Algherese Catalan and Ligurian Tabarchino) spoken on the island are recognized by the regional law and enjoy "equal dignity" with Italian.[7]

It is situated between 38° 51' and 41° 18' latitude north (respectively Isola del Toro and Isola La Presa) and 8° 8' and 9° 50' east longitude (respectively Capo dell'Argentiera and Capo Comino). To the west of Sardinia is the Sea of Sardinia, a unit of the Mediterranean Sea; to Sardinia's east is the Tyrrhenian Sea, which is also an element of the Mediterranean Sea.[8]

Sardinia has few major rivers, the largest being the Tirso, 151 km long, which flows into the Sea of Sardinia, the Coghinas (115 km) and the Flumendosa (127 km). There are 54 artificial lakes and dams that supply water and electricity. The main ones are Lake Omodeo and Lake Coghinas. The only natural freshwater lake is Lago di Baratz. A number of large, shallow, salt-water lagoons and pools are located along the 1,850 km (1,150 mi) of the coastline.

History

Prehistory: Sardinia is one of the most geologically ancient bodies of land in Europe. The island was populated in various waves of immigration from prehistory until recent times.

The first people to settle in Sardinia during the Upper Paleolithic and the Mesolithic came from Continental Europe; the Paleolithic colonization of the island is demonstrated by the evidences in Oliena's Corbeddu Cave;[9] in the Mesolithic some populations, particularly from present-day Tyrrhenian coast of Italy, managed to move to northern Sardinia via Corsica. The Neolithic Revolution was introduced in the 6th millennium BC by the Cardial culture coming from the Italian Peninsula. In the mid-Neolithic period, the Ozieri culture, probably of [Aegean origin]], flourished on the island spreading the hypogeum tombs known as domus de Janas, while the Arzachena culture of Gallura built the first megaliths: circular tombs. In the early 3rd millennium BC, the metallurgy of copper and silver began to develop.

During the late Chalcolithic, the so-called Beaker culture, coming from various parts of Continental Europe, appeared in Sardinia. These new people predominantly settled on the west coast, where the majority of the sites attributed to them had been found.[10] The Beaker culture was followed in the early Bronze Age by the Bonnanaro culture which showed both reminiscences of the Beaker and influences by the Polada culture.

As time passed, the different Sardinian populations appear to have become united in customs, yet remained politically divided into various small, tribal groupings, at times banding together, and at others waging war against each other. Habitations consisted of round thatched stone huts.

Nuragic civilization: From about 1500 BC onwards, villages were built around round tower-fortresses called nuraghi[11] (singular form "Nuraghe", usually pluralized in English as "Nuraghes"). These towers were often reinforced and enlarged with battlements. Tribal boundaries were guarded by smaller lookout Nuraghes erected on strategic hills commanding a view of other territories.

Today, some 7,000 Nuraghes dot the Sardinian landscape. While initially these Nuraghes had a relatively simple structure, with time they became extremely complex and monumental (see for example Nuraghe Santu Antine, Su Nuraxi, or Nuraghe Arrubiu). The scale, complexity and territorial spread of these buildings attest to the level of wealth accumulated by the Nuragic people, their advances in technology and the complexity of their society, which was able to coordinate large numbers of people with different roles for the purpose of building the monumental Nuraghes.

The Nuraghes are not the only Nuragic buildings that survive, as there are several sacred wells around Sardinia and other buildings that had religious purposes such as the Giants' grave (monumental collective tombs) and collections of religious buildings that probably served as destinations for pilgrimage and mass religious rites (e.g. Su Romanzesu near Bitti).

Sardinia was at the time at the centre of several commercial routes and it was an important provider of raw materials such as copper and lead, which were pivotal for the manufacture of the time. By controlling the extraction of these raw materials and by commercializing them with other countries, the Nuragic civilisation was able to accumulate wealth and reach a level of sophistication that is not only reflected in the complexity of its surviving buildings, but also in its artworks (e.g. the votive bronze statuettes found across Sardinia or the statues of Mont'e Prama).

According to some scholars, the Nuragic people(s) are identifiable with the Sherden, a tribe of the "Sea Peoples".[12]

The Nuragic civilization was linked with other contemporaneous megalithic civilization of the western Mediterranean, such as the Talaiotic culture of the Balearic Islands and the Torrean civilization of South Corsica. Evidence of trade with the other civilizations of the time is attested by several artefacts (e.g. pots), coming from as far as Cyprus, Crete, Mainland Greece, Spain and Italy, that have been found in Nuragic sites, bearing witness to the scope of commercial relations between the Nuragic people and other peoples in Europe and beyond.

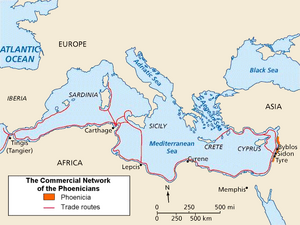

Ancient history: Around the 9th century BC the Phoenicians began visiting Sardinia with increasing frequency, presumably initially needing safe overnight and all-weather anchorages along their trade routes from the coast of modern-day Lebanon as far afield as the African and European Atlantic coasts and beyond. The most common ports of call were Caralis, Nora, Bithia, Sulci, and Tharros. Claudian, a 4th-century Latin poet, in his poem De bello Gildonico, stated that Caralis was founded by people from Tyre, probably in the same time of the foundation of Carthage, in the 9th or 8th century BC.[13]

In the 6th century BC, after the conquest of western Sicily, the Carthaginians planned to annex Sardinia.[14] A first invasion attempt led by Malco was foiled by the victorious Nuraghic resistance. However, from 510 BC, the southern and west-central part of the island was invaded a second time and came under Carthaginian rule.[15][16]

In 238 BC, taking advantage of Carthage having to face a rebellion of her mercenaries (the Mercenary War) after the First Punic War (264–241 BC), the Romans annexed Corsica and Sardinia from the Carthaginians. The two islands became the province of Corsica and Sardinia. They were not given a provincial governor until 227 BC. The Romans faced many rebellions, and it took them many years to pacify both islands. The existing coastal cities were enlarged and embellished, and Roman colonies such as Turris Lybissonis and Feronia were founded. These were populated by Roman immigrants. The Roman military occupation brought the Nuragic civilization to an end, except for the mountainous interior of the island, which the Romans called Barbaria, meaning "Barbarian land". Roman rule in Sardinia lasted 694 years, during which time the province was an important source of grain for the capital. Latin came to be the dominant spoken language during this period, though Roman culture was slower to take hold, and Roman rule was often contested by the Sardinian tribes from the mountainous regions.[17]

Vandal conquest: The east Germanic tribe of the Vandals conquered Sardinia in 456. Their rule lasted for 78 years up to 534, when 400 eastern Roman troops led by Cyril, one of the officers of the foederati, retook the island. It is known that the Vandal government continued the forms of the existing Roman Imperial structure. The governor of Sardinia continued to be called the praeses and apparently continued to manage military, judicial, and civil governmental functions via imperial procedures. The only Vandal governor of Sardinia about whom there is substantial record is the last, Godas, a Visigoth noble. In AD 530, a coup d'état in Carthage removed King Hilderic, a convert to Nicene Christianity, in favor of his cousin Gelimer, an Arian Christian like most of the élite in his kingdom. Godas was sent to take charge and ensure the loyalty of Sardinia. He did the exact opposite, declaring the island's independence from Carthage[27] and opening negotiations with Emperor Justinian I, who had declared war on Hilderic's behalf. In AD 533 Gelimer sent the bulk of his army and navy (120 vessels and 5,000 men) to Sardinia to subdue Godas, with the catastrophic result that the Vandal Kingdom was overwhelmed when Justinian's own army under Belisarius arrived at Carthage in their absence. The Vandal Kingdom ended and Sardinia was returned to Roman rule.[18]

See also

References

- ↑ Nuragica, Archeologia (9 August 2010). "Archeologia Nuragica: Sul nome Sardigna".

- ↑ Platonis dialogi, scholia in Timaeum (edit. C. F. Hermann, Lipsia 1877), 25 B, pag. 368

- ↑ M. Pittau, La Lingua dei Sardi Nuragici e degli Etruschi, Sassari 1981, pag. 57

- ↑ Sardi in Dizionario di Storia (2011), Treccani

- ↑ Sardi in Enciclopedia Italiana (1936), Giacomo Devoto, Treccani

- ↑ "Personaggi – Sardo"

- ↑ "Legge Regionale 15 ottobre 1997, n. 26-Regione Autonoma della Sardegna"

- ↑ C.Michael Hogan. 2011. Balearic Sea. Encyclopedia of Earth. Eds. P.Saundry & C.J.Cleveland. National Council for Science and the Environment. Washington DC

- ↑ Paolo Melis – Un approdo della costa di Castelsardo, fra età nuragica e romana

- ↑ Giovanni Ugas, L'alba dei Nuraghi p.22-23-24-25-29-30-31-32

- ↑ Nuraghes in Logudorese Sardinian, nuraxis in Campidanese Sardinian, plurals of nuraghe and nuraxi respectively.

- ↑ "SP INTERVISTA>GIOVANNI UGAS: SHARDANA".

- ↑ Claudian, De Bello Gildonico, IV A.D.: city located in front of Libya (Africa), founded by the powerful Tyro, Karalis extends in length, between the waves, with a small bumpy hill, disperses headwinds. It follows a port in the mid of the sea, and all strong winds are softened in the shelter of the pond.(521.Urbs Lybiam contra Tyrio fundata potenti 521. Tenditur in longum Caralis, tenuemque per undas 522. Obvia dimittit fracturum flamina collem. 523. Efficitur portus medium mare: tutaque ventis 524. Omnibus, ingenti mansuescunt stagna recessu)

- ↑ Brigaglia, Mastino, Ortu 2006, p. 27.

- ↑ Brigaglia, Mastino, Ortu 2006, p. 27.

- ↑ Piero Meloni, La Sardegna romana, Sassari, Chiarella, 1975, p. 4.

- ↑ "Sardinia - Province of the Roman Empire". www.unrv.com.

- ↑ Andrew Merrills; Richard Miles (2009). The Vandals. John Wiley & Sons. p. 136. ISBN 978-1-4443-1808-1.