Salisbury

Salisbury (Hindi:सल्ज़्बरी, /ˈsɒlzbəri/) is a city in Wiltshire, England. Stonehenge, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is 13 kms northwest of Salisbury.

Location

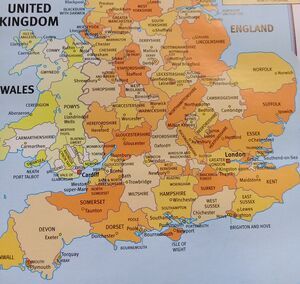

It is located at the confluence of the rivers Nadder, Ebble, Wylye and Bourne. The city is approximately 32 kms from Southampton and 48 km from Bath. Salisbury is in the southeast of Wiltshire, near the edge of Salisbury Plain. Salisbury Cathedral was formerly north of the city at Old Sarum. Following the cathedral's relocation, a settlement grew up around it which received a city charter in 1227 as New Sarum, which continued to be its official name until 2009 when Salisbury City Council was established. Salisbury railway station is an interchange between the West of England Main Line and the Wessex Main Line.

Origin of Name

The name Salisbury, which is first recorded around the year 900 as Searoburg (dative Searobyrig), is a partial translation of the Roman Celtic name Sorviodūnum. The Brittonic suffix -dūnon, meaning "fortress" (in reference to the fort that stood at Old Sarum), was replaced by its Old English equivalent -burg. The first part of the name is of obscure origin. The form "Sarum" is a Latinization of Sar, a medieval abbreviation for Middle English Sarisberie.[1]

The two names for the city, Salisbury and Sarum, are humorously alluded to in a 1928 limerick from Punch:

- There was an old Sultan of Salisbury

- Who wanted some wives for his halisbury,

- So he had them sent down

- By a fast train from town,

- For he thought that his motor would scalisbury.[2]

Salisbury appeared in the Welsh Chronicle of the Britons as Caer-Caradog, Caer-Gradawc and Caer-Wallawg.[3] Cair-Caratauc, one of the 28 British cities listed in the History of the Britons, has also been identified with Salisbury.[4]

History

The hilltop at Old Sarum lies near the Neolithic sites of Stonehenge and Avebury and shows some signs of early settlement.[5]It commanded a salient between the River Bourne and the Hampshire Avon, near a crossroads of several early trade-routes.[6] During the Iron Age, sometime between 600 and 300 BC, a hillfort (oppidum) was constructed around it. The Romans may have occupied the site or left it in the hands of an allied tribe. At the time of the Saxon invasions, Old Sarum fell to King Cynric of Wessex in 552.[12] Preferring settlements in bottomland, such as nearby Wilton, the Saxons largely ignored Old Sarum until the Viking invasions led King Alfred (KIng of Wessex from 871 to 899) to restore its fortifications.[7] Along with Wilton, however, it was abandoned by its residents to be sacked and burned by the Dano-Norwegian king Sweyn Forkbeard in 1003.[8] It subsequently became the site of Wilton's mint. Following the Norman invasion of 1066, a motte-and-bailey castle was constructed by 1070.[9] The castle was held directly by the Norman kings; its castellan was generally also the sheriff of Wiltshire.

In 1075 the Council of London established Herman as the first bishop of Salisbury,[10] uniting his former sees of Sherborne and Ramsbury into a single diocese which covered the counties of Dorset, Wiltshire, and Berkshire. In 1055, Herman had planned to move his seat to Malmesbury, but its monks and Earl Godwin objected.[11] Herman and his successor, Saint Osmund, began the construction of the first Salisbury cathedral, though neither lived to see its completion in 1092.[12] Osmund served as Lord Chancellor of England (in office c. 1070–1078); he was responsible for the codification of the Sarum Rite,[13] the compilation of the Domesday Book, which was probably presented to William at Old Sarum[14], and, after centuries of advocacy from Salisbury's bishops, was finally canonised by Pope Callixtus III in 1457.[15] The cathedral was consecrated on 5 April 1092 but suffered extensive damage in a storm, traditionally said to have occurred only five days later. Bishop Roger was a close ally of Henry I (reigned 1100–1135): he served as viceroy during the king's absence in Normandy[16] and directed, along with his extended family, the royal administration and exchequer.[17] He refurbished and expanded Old Sarum's cathedral in the 1110s and began work on a royal palace during the 1130s, prior to his arrest by Henry's successor, Stephen.[18] After this arrest, the castle at Old Sarum was allowed to fall into disrepair, but the sheriff and castellan continued to administer the area under the king's authority.[19]

New Sarum:

Bishop Hubert Walter was instrumental in the negotiations with Saladin during the Third Crusade, but he spent little time in his diocese prior to his elevation to archbishop of Canterbury.[20] The brothers Herbert and Richard Poore succeeded him and began planning the relocation of the cathedral into the valley almost immediately. Their plans were approved by King Richard I but repeatedly delayed: Herbert was first forced into exile in Normandy in the 1190s by the hostility of his archbishop Walter and then again to Scotland in the 1210s owing to royal hostility following the papal interdiction against King John. The secular authorities were particularly incensed, according to tradition, owing to some of the clerics debauching the castellan's female relations.[21] In the end, the clerics were refused permission to reenter the city walls following their rogations and processions.[22] This caused Peter of Blois to describe the church as "a captive within the walls of the citadel like the ark of God in the profane house of Baal". He advocated

- Let us descend into the plain! There are rich fields and fertile valleys abounding in the fruits of the earth and watered by the living stream. There is a seat for the Virgin Patroness of our church to which the world cannot produce a parallel.[23]

His successor and brother Richard Poore eventually moved the cathedral to a new town on his estate at Veteres Sarisberias ("Old Salisburies") in 1220. The site was at "Myrifield" ("Merryfield"),[24] a meadow near the confluence of the River Nadder and the Hampshire Avon. It was first known as "New Sarum"[25] or New Saresbyri.[26] The town was laid out on a grid.

Salisbury:

The 1972 Local Government Act eliminated the administration of the City of New Sarum under its former charters, but its successor, Wiltshire County's Salisbury District, continued to be accorded its former city status. The name was finally formally amended from "New Sarum" to "Salisbury" during the 2009 changes occasioned by the 1992 Local Government Act, which established the Salisbury City Council.

External links

References

- ↑ Mills, David. A Dictionary of British Place-Names. Oxford University Press, 2003.

- ↑ Reed, Langford (1934). "Irreverent Radios". Mr. Punch's Limerick Book. London: R. Cobden–Sanderson Ltd. p. 65.

- ↑ Roberts, Peter (1811). The Chronicle of the Kings of Britain; Translated from the Welsh Copy Attributed to Tysilio; Collated with Several Other Copies, and Illustrated with Copious Notes; to Which Are Added, Original Dissertations. London: E. Williams. pp. 150–151.

- ↑ 1. Nennius, (Traditional attribution). Mommsen, Theodor. ed (in la). Wikisource link to Historia Brittonum. VI. Wikisource. 2. Newman, John Henry; et al. (1844). "Chapter X: Britain in 429, A.D.". Lives of the English Saints: St. German, Bishop of Auxerre. London: James Toovey. p. 92.

- ↑ English Heritage. Old Sarum, p. 22. (London), 2003.

- ↑ "Salisbury: Thumbnail History". Wiltshire Community History. Wiltshire Council.

- ↑ "Salisbury: Thumbnail History". Wiltshire Community History. Wiltshire Council.

- ↑ Hunt, William (1898). "Sweyn (d.1014)". In Lee, Sidney. Dictionary of National Biography. 55. London: Smith, Elder & Co. p. 202.

- ↑ "Salisbury: Thumbnail History". Wiltshire Community History. Wiltshire Council.

- ↑ British History Online. Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1066–1300, Vol. IV, "Salisbury: Bishops". Institute of Historical Research (London), 1991.

- ↑ Dolan, John Gilbert (1910). "Malmesbury". In Herbermann, Charles. Catholic Encyclopedia. 9. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ↑ British History Online. Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1066–1300, Vol. IV, "Salisbury: Bishops". Institute of Historical Research (London), 1991.

- ↑ Bergh, Frederick T. (1912). "Sarum Rite". In Herbermann, Charles. Catholic Encyclopedia. 13. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ↑ "Salisbury: Thumbnail History". Wiltshire Community History. Wiltshire Council.

- ↑ Swanson, R.N. Religion and Devotion in Europe, c. 1215–c. 1515, pp. 148 & 315. Cambridge University Press (Cambridge), 1995. ISBN 0-521-37950-4.

- ↑ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Roger, bishop of Salisbury". Encyclopædia Britannica. 23 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 454.

- ↑ Davis, R.H.C. (1977). King Stephen. London: Longman. p. 31. ISBN 0-582-48727-7.

- ↑ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Roger, bishop of Salisbury". Encyclopædia Britannica. 23 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 454.

- ↑ Storer, James (1819). History and Antiquities of the Cathedral Churches of Great Britain. 4. London: Rivingtons. p. 73.

- ↑ Frost, Christian (2009). Time, Space, and Order: The Making of Medieval Salisbury. Bern: Peter Lang. p. 34.

- ↑ Storer, James (1819). History and Antiquities of the Cathedral Churches of Great Britain. 4. London: Rivingtons. p. 73.

- ↑ Ledwich 1777, pp. 253 ff. quotes John Leland

- ↑ Prothero, George Walter (1858). The Quarterly Review. John Murray. p. 115.

- ↑ Ledwich, Edward (1777). "Appendix of Original Records, with Observations". Antiquitates Sariſburienſes: The History and Antiquities of Old and New Sarum Collected from Original Records and Early Writers. Salisbury: E. Easton etc. p. 260.

- ↑ Prothero, George Walter (1858). The Quarterly Review. John Murray. p. 115

- ↑ Ledwich, Edward (1777). "Appendix of Original Records, with Observations". Antiquitates Sariſburienſes: The History and Antiquities of Old and New Sarum Collected from Original Records and Early Writers. Salisbury: E. Easton etc. pp. 253 ff.