Hampshire

| Author:Laxman Burdak, IFS (R) |

Hampshire is a county on the southern coast of England in the United Kingdom. The county town of Hampshire is Winchester, the former capital city of England.[1]

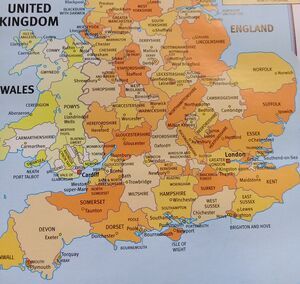

Location

Hampshire is bordered by Dorset to the west, Wiltshire to the north-west, Berkshire to the north, Surrey to the north-east, and West Sussex to the east. The southern boundary is the coastline of the English Channel and the Solent, facing the Isle of Wight. It is the largest county in South East England.

Hampshire's tourist attractions include many seaside resorts and two National Parks: the New Forest and the South Downs (together covering some 45% of the county).

Origin of Name

Hampshire takes its name from the settlement that is now the city of Southampton. Southampton was known in Old English as Hamtun, roughly meaning "village-town", so its surrounding area or scīr became known as Hamtunscīr. The old name was recorded in the Domesday book as Hantescire, and from this spelling, the modern abbreviation "Hants" derives.[2] From 1889 until 1959, the administrative county was named the County of Southampton[3] [4] and has also been known as Southamptonshire.[5][6]

Hampshire was the departure point of some of those who left England to settle on the east coast of North America during the 17th century, giving its name in particular to the state of New Hampshire.[7] The town of Portsmouth, Virginia, takes its name from Portsmouth in Hampshire.[8]

History

The county has a long maritime history, and today Southampton and Portsmouth remain prominent ports. The county is known as the home of writers Jane Austen and Charles Dickens, the childhood home of Florence Nightingale and the birthplace of engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

Prehistory until the Norman Conquest

The region is believed to have been continuously occupied since the end of the last Ice Age about 12,000 BCE.[9] At this time, Britain was still attached to the European continent and was predominantly covered with deciduous woodland. The first inhabitants were Mesolithic hunter-gatherers.[10] The majority of the population would have been concentrated around the river valleys.[11] Over several thousand years, the climate became progressively warmer, and sea levels rose; the English Channel, which started out as a river, was a major inlet by 8000 BCE, although Britain was still connected to Europe by a land bridge across the North Sea until 6500 BCE.[12] Notable sites from this period include Bouldnor Cliff.[13]

Agriculture had arrived in southern Britain by 4000 BCE, and with it a neolithic culture. Some deforestation took place at that time, although during the Bronze Age, beginning in 2200 BCE, this became more widespread and systematic.[14] Hampshire has few monuments to show from these early periods, although nearby Stonehenge was built in several phases at some time between 3100 and 2200 BCE. In the very late Bronze Age, fortified hilltop settlements known as hillforts began to appear in large numbers in many parts of Britain including Hampshire, and these became more and more important in the early and middle Iron Age;[15] many of these are still visible in the landscape today and can be visited, notably Danebury Rings, the subject of a major study by archaeologist Barry Cunliffe. By this period, the people of Britain predominantly spoke a Celtic language, and their culture shared much in common with the Celts described by classical writers.[16]

Hillforts largely declined in importance in the second half of the second century BCE, with many being abandoned. Probably around this period, the first recorded invasion of Britain took place, as southern Britain was largely conquered by warrior-elites from Belgic tribes of northeastern Gaul - whether these two events are linked to the decline of hillforts is unknown. By the Roman conquest, the oppidum at Venta Belgarum, modern-day Winchester, was the de facto regional administrative centre; Winchester was, however, of secondary importance to the Roman-style town of Calleva Atrebatum, modern Silchester, built further north by a dominant Belgic polity known as the Atrebates in the 50s BCE. Julius Caesar invaded southeastern England briefly in 55 and again in 54 BCE, but he never reached Hampshire. Notable sites from this period include Hengistbury Head (now in Dorset), which was a major port.[17][18]

The Romans invaded Britain again in 43 CE, and Hampshire was incorporated into the Roman province of Britannia very quickly. It is generally believed their political leaders allowed themselves to be incorporated peacefully. Venta became the capital of the administrative polity of the Belgae, which included most of Hampshire and Wiltshire and reached as far as Bath. Whether the people of Hampshire played any role in Boudicca's rebellion of 60-61 CE is not recorded, but evidence of burning is seen in Winchester dated to around this period.[19] For most of the next three centuries, southern Britain enjoyed relative peace. The later part of the Roman period had most towns build defensive walls; a pottery industry based in the New Forest exported items widely across southern Britain. A fortification near Southampton was called Clausentum, part of the Saxon Shore forts, traditionally seen as defences against maritime raids by Germanic tribes. The Romans withdrew from Britain in 410 CE.[20]

Two major Roman roads, Ermin Way and Port Way cross the north of the country connecting Calleva Atrebatum with Corinium Dobunnorum, modern Cirencester, and Old Sarum respectively. Other roads connected Venta Belgarum with Old Sarum, Wickham and Clausentum. A road, presumed to diverge from the Chichester to Silchester Way at Wickham, connected Noviomagus Reginorum, modern Chichester, with Clausentum.[21]

Records are unreliable for the next 200 years, but in this time, southern Britain went from being Brythonic to being English and Hampshire emerged as the centre of what was to become the most powerful kingdom in Britain, the Kingdom of Wessex. Evidence of early Anglo-Saxon settlement has been found at Clausentum, dated to the fifth century. By the seventh century, the population of Hampshire was predominantly English-speaking; around this period, the administrative region of "Hampshire" seems to appear; the name is attested as "Hamtunscir" in 755,[22] and Albany Major suggested that the traditional western and northern borders of Hampshire may even go back to the very earliest conquests of Cerdic, legendary founder of Wessex, at the beginning of the sixth century.[23] Wessex gradually expanded westwards into Brythonic Dorset and Somerset in the seventh century. A statue in Winchester celebrates the powerful King Alfred, who repulsed the Vikings and stabilised the region in the 9th century. A scholar as well as a soldier, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a powerful tool in the development of the English identity, was commissioned in his reign. King Alfred proclaimed himself "King of England" in 886; but Athelstan of Wessex did not officially control the whole of England until 927.[24][25][26]

Middle Ages onwards

By the Norman conquest, London had overtaken Winchester as the largest city in England[27]and after the Norman Conquest, King William I made London his capital. While the centre of political power moved away from Hampshire, Winchester remained an important city; the proximity of the New Forest to Winchester made it a prized royal hunting forest; King William Rufus was killed while hunting there in 1100. The county was recorded in the Domesday Book divided into 44 hundreds.

From the 12th century, the ports grew in importance, fuelled by trade with the continent, wool and cloth manufacture in the county, and the fishing industry, and a shipbuilding industry was established. By 1523 at the latest, the population of Southampton had outstripped that of Winchester. Portsmouth historic dockyard, 2005

Over several centuries, a series of castles and forts was constructed along the coast of the Solent to defend the harbours at Southampton and Portsmouth. These include the Roman Portchester Castle which overlooks Portsmouth Harbour, and a series of forts built by Henry VIII including Hurst Castle, situated on a sand spit at the mouth of the Solent, Calshot Castle on another spit at the mouth of Southampton Water, and Netley Castle. Southampton and Portsmouth remained important harbours when rivals, such as Poole and Bristol, declined, as they are amongst the few locations that combine shelter with deep water. Mayflower and Speedwell set sail for America from Southampton in 1620.[28]

During the English Civil War (1642-1651) there were several skirmishes in Hampshire between the Royalist and Parliamentarian forces. Principal engagements were the Siege of Basing House between 1643 and 1645, and the Battle of Cheriton in 1644; both were significant Parliamentarian victories. Other clashes included the Battle of Alton in 1643, where the commander of the Royalist forces was killed in the pulpit of the parish church,[29] and the Siege of Portsmouth in 1642.[30]

By the mid-19th century, with the county's population at 219,210 (double that at the beginning of the century) in more than 86,000 dwellings, agriculture was the principal industry (10 per cent of the county was still forest) with cereals, peas, hops, honey, sheep and hogs important. Due to Hampshire's long association with pigs and boars, natives of the county have been known as Hampshire hogs since the 18th century.[31] In the eastern part of the county the principal port was Portsmouth (with its naval base, population 95,000), while several ports (including Southampton, with its steam docks, population 47,000) in the western part were significant. In 1868, the number of people employed in manufacture exceeded those in agriculture, engaged in silk, paper, sugar and lace industries, ship building and salt works. Coastal towns engaged in fishing and exporting agricultural produce. Several places were popular for seasonal sea bathing.[32] The ports employed large numbers of workers, both land-based and seagoing; Titanic, lost on her maiden voyage in 1912, was crewed largely by residents of Southampton.[33]

Jat History

Kent Kingdom was a Kingdom of Jats in England. The Kingdom of Kent was founded by Jutes in southeast England, one of the seven traditional kingdoms of the so-called Anglo-Saxon heptarchy.

Jwala Sahai[34] writes... Mr. Keene in his Fall of the Mugal Empire says:- "Wherever they (the Jats) are found, they are stout yeomen; able to cultivate their fields and to protect them, and with strong administrative habits of a somewhat republican cast. Within half a century, they have four times tried conclusions with the might of Britain, The Juts of Bharatpur fought Lord Lake with success and Lord Combermere with credit; and their Sikh brethren in the Panjab shook the whole fabric of British India on the Satlaj in 1845 and three years later on the field of Chilianwala. It is interesting to note further that some ethnologists have regarded this fine people as of kin to ancient Getae and to the Goths of Europe by whom not only Jutland but parts of the south-east of England and Spain were overrun and to some extent peopled. It is therefore possible that, yeomen of Kent and Hampshire have blood relation in the natives. of Bharatpur and the Panjab."

Its origins are completely obscure, since by its geographical position it received some of the first waves of the invasion by the Germanic tribes, at a time from which almost no historical information has survived. The name "Kent" predates the Jutish invaders, and relates to the much earlier Celtic Cantiaci tribe whose homeland it was.

During the British rule over India, colonizers and scholars noticed to their astonishment that many Jat people had apparently English family names or very similar. Certainly the proud Jats would have never adopted British surnames for their own ancestral clans, and they did not result from intermarriage either. Other foreign powers ruled over the Indus Valley before and for longer periods than England, yet no Jat clan names corresponding to the previous rulers have been found. Besides this, no other Indian people had such names except Jats.

This peculiarity led scholars to research about these Jat-British homonyms: those names in England may be traced back to a Jut origin, mainly Kentish; among the Jats, they exist since the distant past. This appears to be more than a coincidence; Jats and Juts are the same people.

This assertion finds confirmation in historic records, for example, the Roman writer Ammianus Marcellinus, who called all Sarmatian peoples "Alani", wrote: "Alani once were known as the Massagetae. The Alani mount to the eastward, divided into populous and extensive nations; these reach as far as Asia and, as I have heard, stretch all the way to the river Ganges, which flows through the territories of India".

British scholars and also officers compared the Jats' warrior character with that of the Kentish men as well as their traditional laws, for instance, the double heritage part for the youngest son, still practised among Indian Jats. An accurate research about this people which takes account of all the relevant characteristics of their ethnicity reveals that they are among the purest Sarmatic tribes existing today.

The Jats undoubtedly descend from the easternmost branch of the Sarmatian people, the Yazyg of Central Asia, that curiously have the same name of the westernmost branch in the Danubian region: Jász, Jat, Jut.

References

- ↑ Hadfield, John, ed. (1977). The Shell Guide to England. Book Club Associates. p. 303.

- ↑ "About Hampshire". Hampshire County Council.

- ↑ "County of Hants (Southampton)". Census of England and Wales: 1891: Area, Houses and Population: Volume 1. Her Majesty's Stationery Office. p. 121.

- ↑ "Local Government Act 1959: Section 59: Change of Name of County". The London Gazette. 20 February 1959. p. 1241.

- ↑ "Vision of Britain".

- ↑ "National Gazetteer". 1868.

- ↑ "Origin of 'New Hampshire'". State Symbols USA.

- ↑ "The City of Portsmouth, Virginia: History".

- ↑ Oppenheimer, S, 2006, The Origins of the British

- ↑ "The British Museum: Prehistoric Britain" (PDF). p. 6.

- ↑ "Hampshire County Council: The Atlas of Hampshire's Archaeology" (PDF).

- ↑ Gaffney, V, Fitch, S, and Smith, D, 2009, Europe's Lost World: The rediscovery of Doggerland

- ↑ "Bouldnor Cliff". Maritime Archaeology Trust.

- ↑ Pryor, F, 2003, Britain BC

- ↑ Cunliffe, B, 2008, Iron Age Communities in Britain, fourth edition

- ↑ Cunliffe, B, 1997, The Ancient Celts

- ↑ Cunliffe, B, 1997, The Ancient Celts

- ↑ Cunliffe, B, 1997, The Ancient Celts

- ↑ Cunliffe, B, 1991, Wessex to AD 1000, p.218

- ↑ Cunliffe, B, 1991, Wessex to AD 1000; de la Bedoyere, Guy, 2006, Roman Britain: A New History; Pryor, F, 2004, Britain AD

- ↑ Davies, Hugh (2002). Roads in Roman Britain. Stroud: Tempus. pp. 168–183. ISBN 0-7524-2503-X.

- ↑ Grant, Russell (1989). The Real Counties of Britain. Oxford: Lennard Publishing. p. 61. ISBN 1-85291-071-2.

- ↑ Major, Albany F Early Wars of Wessex (1912, 1978) p.17

- ↑ Cunliffe, B, 1991, Wessex to AD 1000

- ↑ Pryor, F, 2004, Britain AD

- ↑ Hinley, G, 2006, A Brief History of the Anglo-Saxons; Fleming, R, 2010, Britain After Rome: The Fall and Rise 400 to 1070

- ↑ Hingley G. A Brief History of the Anglo-Saxons' 2006

- ↑ Ian Crump (29 December 2017). "A look back at when the Mayflower and Speedwell left Southampton bound for America". Southern Daily Echo.

- ↑ Mee, Arthur (1967). The King's England - Hampshire and the Isle of Wight. London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 0 340 00083 X.

- ↑ Webb, John (1977). The Siege of Portsmouth in the Civil War. Portsmouth City Council. ISBN 0-901559-33-4.

- ↑ Hampshire County Council, 2003. "Press Release: Hampshire's Hog has a home

- ↑ "National Gazetteer". 1868.

- ↑ Barratt, Nick (2009). Lost Voices From the Titanic: The Definitive Oral History. London: Random House. p. 84. ISBN 978-1-84809-151-1.

- ↑ History of Bharatpur/Chapter I By Jwala Sahai, p.2-3