Sussex

| Author:Laxman Burdak, IFS (R) |

Sussex (Hindi:ससीक्स, सस्सेक्स, /ˈsʌsɪks/ )is a historic county in South East England corresponding roughly in area to the ancient Kingdom of Sussex.

Origin of name

Sussex derives name from the Old English Sūþsēaxe (South Saxons).

Location

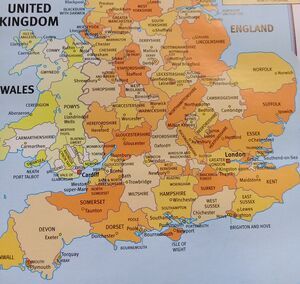

It is bounded to the west by Hampshire, north by Surrey, northeast by Kent, south by the English Channel, and divided for many purposes into the ceremonial counties of West Sussex and East Sussex. Brighton and Hove, though part of East Sussex, was made a unitary authority in 1997, and as such, is administered independently of the rest of East Sussex. Brighton and Hove was granted City status in 2000. Until then, Chichester was Sussex's only city.

Sussex has three main geographic sub-regions, each oriented approximately east to west. In the southwest is the fertile and densely populated coastal plain. North of this are the rolling chalk hills of the South Downs, beyond which is the well-wooded Sussex Weald.

Origin

The name "Sussex" is derived from the Middle English Suth-sæxe, which is in turn derived from the Old English Suth-Seaxe which means (land or people) of the South Saxons[1] (cf. Essex, Middlesex and Wessex). The South Saxons were a Germanic tribe that settled in the region from the North German Plain during the 5th and 6th centuries.

The earliest known usage of the term South Saxons (Latin: Australes Saxones) is in a royal charter of 689 which names them and their king, Noðhelm, although the term may well have been in use for some time before that. The monastic chronicler who wrote up the entry classifying the invasion seems to have got his dates wrong; recent scholars have suggested he might have been a quarter of a century too late.[2]

The New Latin word Suthsexia was used for Sussex by Dutch cartographer Joan Blaeu in his 1645 map.[3]

Three United States counties (in Delaware, New Jersey, and Virginia), and a former county/land division of Western Australia, are named after Sussex.

History

The name derives from the Kingdom of Sussex, which was founded, according to legend, by Ælle of Sussex in AD 477. Around 827, it was absorbed into the kingdom of Wessex[4] and subsequently into the kingdom of England. It was the home of some of Europe's earliest hominids, whose remains have been found at Boxgrove. It was invaded by the Romans and is the site of the Battle of Hastings.

In 1974, the Lord-Lieutenant of Sussex was replaced with one each for East and West Sussex, which became separate ceremonial counties. Sussex continues to be recognised as a geographical territory and cultural region. It has had a single police force since 1968 and its name is in common use in the media.[5] In 2007, Sussex Day was created to celebrate the county's rich culture and history. Based on the traditional emblem of Sussex, a blue shield with six gold martlets, the flag of Sussex was recognised by the Flag Institute in 2011. In 2013, Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government Eric Pickles formally recognised and acknowledged the continued existence of England's 39 historic counties, including Sussex.[6][7][8]

Beginnings:

Finds at Eartham Pit in Boxgrove show that the area has some of the earliest hominid remains in Europe, dating back some 500,000 years and known as Boxgrove Man or Homo heidelbergensis. At a site near Pulborough called The Beedings, tools have been found that date from around 35,000 years ago and that are thought to be from either the last Neanderthals in northern Europe or pioneer populations of modern humans.[9] The thriving population lived by hunting game such as horses, bison, mammoth and woolly rhinos.[10] Around 6000BC the ice sheet over the North Sea melted, sea levels rose and the meltwaters burst south and westwards, creating the English Channel and cutting the people of Sussex off from their Mesolithic kinsmen to the south. Later in the Neolithic period, the area of the South Downs above Worthing was one of Britain's largest and most important flint-mining centres.[11] The flints were used to help fell trees for agriculture. The oldest of these mines, at Church Hill in Findon, has been carbon-dated to 4500BC to 3750BC, making it one of the earliest known mines in Britain. Flint tools from Cissbury have been found as far away as the eastern Mediterranean.[12]

Sussex is rich in remains from the Bronze and Iron Ages, in particular the Bronze Age barrows known as the Devil's Jumps and Cissbury Ring, one of Britain's largest hillforts. Towards the end of the Iron Age in 75BC people from the Atrebates, one of the tribes of the Belgae, a mix of Celtic and German stock, started invading and occupying southern Britain.[13] This was followed by an invasion by the Roman army under Julius Caesar that temporarily occupied the south-east in 55BC. Soon after the first Roman invasion had ended, the Celtic Regnenses tribe under their leader Commius occupied the Manhood Peninsula.[24] Tincomarus and then Cogidubnus followed Commius as rulers of the Regnenses.[14]

At the time of the Roman conquest in AD43, there was an oppidum in the southern part of their territory, probably in the Selsey region.[15] A number of archaeologists now think there is a strong possibility that the Roman invasion of Britain in AD-43 started around Fishbourne and Chichester Harbour rather than the traditional landing place of Richborough in Kent. According to this theory, the Romans were called to restore the refugee Verica, king of the Atrebates, who had been driven out by the Catuvellauni, a tribe based around modern Hertfordshire.[16]

Sussex was home to the magnificent Roman Palace at Fishbourne, by far the largest Roman residence known north of the Alps. Much of Sussex was a Roman canton of the Regnenses or Regni, with its capital at Noviomagus Reginorum, modern-day Chichester. The Romans built villas, especially on the coastal plain and around Chichester, one of the best preserved being that at Bignor. Christianity first came to Sussex at this time, but faded away when the Romans left in the 5th century. The nationally important Patching hoard of Roman coins that was found in 1997 is the latest find of Roman coins found in Britain, probably deposited after 475 AD, well after the Roman departure from Britain around 410 AD.[17]

The foundation legend of Sussex is provided by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which states that in the year AD 477 Ælle landed with his three sons.[18] Having fought on the banks of the Mearcredesburna,[19] it seems Aelle secured the area between the Ouse and Cuckmere in a treaty.[20] After Aelle’s forces seized the Saxon Shore fort of Anderida, the South Saxons were able to gradually colonise free of Romano-British control and extend their territory westwards to link with the Saxon settlement at Highdown Hill.[21] Aelle was recognised as the first 'Bretwalda' or overlord of southern Britain. He was probably the most senior of the Anglo-Saxon kings and led the ill-fated campaign against King Arthur at Mount Badon.

An engraving, which is a 17th-century copy, of an earlier painted Tudor mural in Chichester cathedral depicting Cædwalla confirming the granting of land to Wilfrid to build his monastery in Selsey.

By the end of the 7th century, the region around Selsey and Chichester had become the political centre of the kingdom. In the 660s-670s, King Aethelwealh of Sussex formed an alliance with the Mercian king Wulfhere and together they took the Isle of Wight from the West Saxons, probably at the battle of Biedanheafele. As Mercia's first Christian king, Wulfhere insisted that Æthelwealh also convert to Christianity. Æthelwealh was baptised in Mercia, with Wulfhere as his sponsor. Wulfhere gave the Isle of Wight and Meon Valley to Aethelwealh, with Wulfhere acting as overlord. The alliance with Mercia was sealed with Æthelwealh taking the hand of Eabe, a Mercian princess in marriage.

Wilfrid, the exiled bishop of York, came to Sussex in 681 and with King Æthelwealh's approval set up a mission to convert the people of Sussex to Christianity. Æthelwealh gave Wilfrid land on the Manhood peninsula, close to his own royal estate and Wilfrid founded Selsey Abbey. The mission was jeopardised when King Æthelwealh was killed by Cædwalla, a prince of Wessex. Cædwalla confirmed Æthelwealh's grant of land and Wilfrid built his Selsey Abbey. Cædwalla was driven out by the South Saxon nobles Berthun and Andhun.

The South Saxons fought off the West Saxons in 722 and again in 725. At the end of the 8th century, Ealdwulf was perhaps the last independent king of Sussex, after which Sussex and other southern kingdoms came increasingly under Mercian rule. Mercia's grip was shattered in 825 at the battle of Ellendun, after which Sussex and the other southern kingdoms came under the control of Wessex, which later grew into the kingdom of England.

Sussex was the venue for the momentous Battle of Hastings, the decisive victory in the Norman conquest of England. In September 1066, William of Normandy landed with his forces at Pevensey and erected a wooden castle at Hastings, from which they raided the surrounding area.[22] The battle was fought between Duke William of Normandy and the English king, Harold Godwinson, who had strong connections with Sussex and whose chief seat was probably in Bosham.[23] After having marched his exhausted army all the way from Yorkshire, Harold fought the Normans at the Battle of Hastings, where England's army was defeated and Harold was killed. It is likely that all the fighting men of Sussex were at the battle, as the county's thegns were decimated and any that survived had their lands confiscated.[24] William built Battle Abbey at the site of the battle, with the exact spot where Harold fell marked by the high altar.[25]

Sussex experienced some of the greatest changes of any English county under the Normans, for it was the heartland of King Harold and was potentially vulnerable to further invasion.[26] The county was of great importance to the Normans; Hastings and Pevensey being on the most direct route for Normandy.[27] The county's existing sub-divisions, known as rapes, were made into castleries and each territory was given to one of William's most trusted barons. Castles were built to defend the territories including at Arundel, Bramber, Lewes, Pevensey and Hastings. Sussex's bishop, Æthelric II, was deposed and imprisoned and replaced with William the Conqueror's personal chaplain, Stigand.[28] The Normans also built Chichester Cathedral and moved the seat of Sussex's bishopric from Selsey to Chichester. The Normans also founded new towns in Sussex, including New Shoreham (the centre of modern Shoreham-by-Sea), Battle, Arundel, Uckfield and Winchelsea.[29]

In 1264, the Sussex Downs were the location of the Battle of Lewes, in which Simon de Montfort and his fellow barons captured Prince Edward (later Edward I), the son and heir of Henry III. The subsequent treaty, known as the Mise of Lewes, led to Montfort summoning the first parliament in English history without any prior royal authorisation. A provisional administration was set up, consisting of Montfort, the Bishop of Chichester and the Earl of Gloucester. These three were to elect a council of nine, to govern until a permanent settlement could be reached.[30] Sussex under the Plantagenets

During the Hundred Years' War, Sussex found itself on the frontline, convenient both for intended invasions and retaliatory expeditions by licensed French pirates. Hastings, Rye and Winchelsea were all burnt during this period and all three towns became part of the Cinque Ports, a loose federation for supplying ships for the country's security. Also at this time, Amberley and Bodiam castles were built to defend the upper reaches of navigable rivers.[31]

Early modern Sussex:

Like the rest of the country, the Church of England's split with Rome during the reign of Henry VIII was felt in Sussex.[32]In 1538 there was a royal order for the demolition of the shrine of Saint Richard, in Chichester Cathedral,[33] with Thomas Cromwell saying that there was "a certain kind of idolatry about the shrine".[34] In the reign of Queen Mary, 41 people in Sussex were burnt at the stake for their Protestant beliefs.[35] Elizabeth re-established the break with Rome when she passed the 1559 Acts of Supremacy and Uniformity. Under Elizabeth I, religious intolerance continued albeit on a lesser scale, with several people being executed for their Catholic beliefs.[36]

Sussex escaped the worst ravages of the English Civil War, although in 1642 there were sieges at Arundel and Chichester, and a skirmish at Haywards Heath when Royalists marching towards Lewes were intercepted by local Parliamentarians. The Royalists were routed with around 200 killed or taken prisoner.[37] Despite its being under Parliamentarian control, Charles II was able to journey through the county after the Battle of Worcester in 1651 to make his escape to France from the port of Shoreham.

Late modern and contemporary Sussex:

The Sussex coast was greatly modified by the social movement of sea bathing for health which became fashionable among the wealthy in the second half of the 18th century. Resorts developed all along the coast, including at Brighton, Hastings, Worthing, and Bognor.[38] At the beginning of the 19th century agricultural labourers' conditions took a turn for the worse with an increasing amount of them becoming unemployed, those in work faced their wages being forced down. Conditions became so bad that it was even reported to the House of Lords in 1830 that four harvest labourers (seasonal workers) had been found dead of starvation. The deteriorating conditions of work for the agricultural labourer eventually triggered riots, first in neighbouring Kent, and then in Sussex, where they lasted for several weeks, although the unrest continued until 1832 and became known as the Swing Riots.[39]

Railways spread across Sussex in the 19th century and county councils were created for Sussex's eastern and western divisions in 1889.

During World War I, on the eve of the Battle of the Somme on 30 June 1916, the Royal Sussex Regiment took part in the Battle of the Boar's Head at Richebourg-l'Avoué. The day subsequently became known as The Day Sussex Died. Over a period of less than five hours the 17 officers and 349 men were killed, including 12 sets of brothers, including three from one family.[45] A further 1,000 men were wounded or taken prisoner.[40]

With the declaration of the World War II, Sussex found itself part of the country's frontline with its airfields playing a key role in the Battle of Britain and with its towns being some of the most frequently bombed.[41] As the Sussex regiments served overseas, the defence of the county was undertaken by units of the Home Guard with help from the First Canadian Army.[42] During the lead up to the D-Day landings, the people of Sussex were witness to the buildup of military personnel and materials, including the assembly of landing crafts and construction of Mulberry harbours off the county's coast.[43]

In the post-war era, the New Towns Act 1946 designated Crawley as the site of a new town.[44] As part of the Local Government Act 1972, the eastern and western divisions of Sussex were made into the ceremonial counties of East and West Sussex in 1974. Boundaries were changed and a large part of the rape of Lewes was transferred from the eastern division into West Sussex, along with Gatwick Airport, which was historically part of the county of Surrey.

ब्रिटेन पर जूट्स, सेक्सन्स एंगल्स की विजय (410 ई० से 825 ई०)

दलीप सिंह अहलावत[45] लिखते हैं: जूट्स, सेक्सन्स और एंगल्स लोग जर्मनी की एल्ब नदी के मुहाने और डेन्मार्क के तट पर रहते थे। ये लोग बड़े बहादुर थे तथा लूटमार किया करते थे। ये क्रिश्चियन धर्म के विरोधी थे।

ब्रिटेन से रोमनों के चले जाने के बाद ब्रिटेन के लोग बहुत कमजोर और असहाय थे। इन लोगों पर स्काटलैंड के केल्टिक कबीलों, पिक्ट्स और स्काट्स ने हमला कर दिया। ब्रिटेन निवासियों की इसमें भारी हानि हुई। इनमें इतनी शक्ति न थी कि वे इन हमलों करने वालों को रोक सकें। इसलिए मदद के लिए इन्होंने जूट लोगों को बुलाया। जूट्स ने उसी समय ब्रिटिश सरदार वरटिगर्न के निमन्त्रण को स्वीकार कर लिया। जटलैण्ड से जाटों की एक विशाल सेना अपने जाट नेता हेंगिस्ट और होरसा के नेतृत्व में सन् 449 ई० में केण्ट (Kent) में उतर गई। इन्होंने पिक्ट्स और स्कॉट्स को हराया और वहां से बाहर निकाल दिया। उन्हें भगाने के बाद जाट ब्रिटेन के लोगों के विरुद्ध हो गये और उन्हें पूरी तरह से अपने वश में कर लिया और 472 ई० तक पूरे केण्ट पर अधिकार कर लिया। यहां पर आबाद हो गये। इसके अतिरिक्त जाटों ने अपना निवास व्हिट द्वीप में किया1।

जटलैण्ड के जाटों की विजय सुनकर उनके दक्षिणवासी सेक्सन्स तथा एंगल्स भी ललचाये। सर्वप्रथम सेक्सन्स ब्रिटेन में पहुंचे और उन्होंने ऐस्सेक्स, मिडिलसेक्स और वेस्सेक्स नाम से तीन राज्य स्थापित किये। वहां पर इन्होंने कुछ बस्तियां आबाद कर दीं। ब्रिटेन की जनता ने बड़ी वीरता से सेक्सन्स का मुकाबला किया और 520 ई० में मोण्डबेडन ने उन्हें करारी हार दी। इस तरह से

- 1. आधार लेख - इंगलैण्ड का इतिहास पृ० 16-17, लेखक प्रो० विशनदास; हिस्ट्री ऑफ ब्रिटेन पृ० 21-22, लेखक रामकुमार लूथरा, अनटिक्विटी ऑफ जाट रेस, पृ० 63-66, लेखक: उजागरसिंह माहिल; जाट्स दी ऐन्शन्ट रूलर्ज पृ० 86 लेखक बी० एस० दहिया तथा जाट इतिहास अंग्रेजी पृ० 43, लेखक ले० रामसरूप जून।

जाट वीरों का इतिहास: दलीप सिंह अहलावत, पृष्ठान्त-399

सेक्सन्स का बढ़ना कुछ समय के लिए रुक गया। परन्तु 577 ई० में डियोरहम की लड़ाई में सेक्सन्स ने केब्लिन के नेतृत्व में ब्रिटेन लोगों पर पूरी विजय प्राप्त कर ली तथा उनको अपना दास बनाए रखा। यह कामयाबी जूट्स (जाटों) की सहायता से हुई थी जिसके लिए सेक्सन्स ने उनसे मांग की थी1।

अब प्रश्न पैदा होता है कि उन जूट्स (जाटों) का क्या हुआ जिन्होंने हेंगिस्ट और होरसा के नेतृत्व में ब्रिटेन के एक बड़े क्षेत्र पर अधिकार कर लिया था और सेक्सन्स को सहायता देकर उनका ब्रिटेन पर अधिकार करवाया। इसका उत्तर यही हो सकता है कि ब्रिटिश इतिहासकारों ने इनके इतिहास को लिखने में पक्षपात किया है।

सेक्सन्स के बाद एंग्ल्स पहुंचे जो जूट्स और सेक्सन्स की तरह ही लड़ाके तथा लुटेरे थे। सन् 613 ई० में नार्थम्ब्रिया के एंग्ल राजा ने ब्रिटेन पर आक्रमण करके विजय प्राप्त की। इसके बाद इन्हीं एगल्स के नाम पर ब्रिटेन का नाम इंग्लैंड हो गया। ये एंगल्स लोग भी जाट थे जैसा कि पिछले पृष्ठों पर लिखा गया है। इंग्लैंड में रहने वालों को अंग्रेज कहा गया।

एंगल्स लोग संख्या में दूसरों से अधिक थे इसी कारण से ब्रिटेन को एंगल्स की भूमि एवं इंग्लैंड कहा गया। इस तरह से ब्रिटेन पर जूट्स, सेक्सन्स और एंगल्स का अधिकार हो गया। इसी को ब्रिटेन पर अंग्रेजों की जीत कहा जाता है। इन तीनों कबीलों ने अपने अलग-अलग राज्य स्थापित किए।

- जूट्स ने केण्ट (Kent);

- सैक्सन्स ने सस्सेक्स (Sussex), एस्सेक्स (Essex), वेसेक्स (Wessex) और

- एंगल्स ने ईस्ट एंगलिया (East Anglia), मर्शिया (Mercia) और नार्थम्ब्रिया (Northumbria) के राज्य स्थापित किये।

ये सातों राज्य सामूहिक रूप से हेपटार्की कहलाते थे। परन्तु ये राज्य स्वतन्त्र नहीं थे। इन सातों में जो शक्तिशाली होता था वह दूसरों का शासक बन जाता था।

ऊपर कहे हुए तीनों कबीले संगठित नहीं थे। नॉरमनों ने जब तक इस देश को नहीं जीता, इंग्लैंड में शक्तिशाली केन्द्रीय राज्य की स्थापना नहीं हो सकी। इन कबीलों ने देश से क्रिश्चियन धर्म और रोमन सभ्यता को मिटा दिया। आधुनिक इंग्लैंड एंग्लो-सैक्सन्स का बनाया हुआ है। आधुनिक अंग्रेज किसी न किसी रूप में इंग्लो-सैक्सन्स के ही वंशज हैं।

अंग्रेज जाति की उत्पत्ति और बनावट के सम्बन्ध में दो प्रतिद्वन्द्वी सिद्धान्त हैं।

- पलग्रोव, पियरसन और सेछम आदि प्रवीण मनुष्य रोमन केल्टिक सिद्धान्त को मानते हैं। उनका यह विचार है कि आधुनिक इंग्लैंड में रोमन-केल्टिक रक्त और संस्थाएं मौजूद हैं।

- ग्रीन और स्टब्स जैसे दूसरे प्रवीन मनुष्य ट्यूटानिक सिद्धान्त को मानते हैं। उनका यह विचार है कि ट्यूटानिक अर्थात् जूट, एंगल, सैक्सन और डेन लोगों का रक्त और संस्थाएं बहुत कुछ आधुनिक इंग्लैंड में पाई जाती हैं। इन दोनों में से ट्यूटानिक सिद्धान्त अधिक माना जाता

- 1. आधार लेख - इंग्लैण्ड का इतिहास पृ० 16-17, लेखक प्रो० विशनदास; ए हिस्ट्री ऑफ ब्रिटेन पृ० 21-22, लेखक रामकुमार लूथरा; अनटिक्विटी ऑफ जाट रेस, पृ० 63-66, लेखक: उजागरसिंह माहिल; जाट्स दी ऐन्शन्ट रूलर्ज पृ० 86 लेखक: बी० एस० दहिया तथा जाट इतिहास अंग्रेजी पृ० 43, लेखक ले० रामसरूप जून।

जाट वीरों का इतिहास: दलीप सिंह अहलावत, पृष्ठान्त-400

- है और आमतौर पर यह स्वीकार किया जाता है कि ब्रिटिश जाति मिले-जुले लोगों की जाति है। जिनमें ट्यूटानिक तत्त्व प्रधान है, जबकि केल्टिक तत्त्व भी पश्चिम में और आयरलैंड में बहुत कुछ बचा हुआ है1।

इसका सार यह है कि इंगलैंड द्वीपसमूह के मनुष्यों की रगों में आज भी अधिकतर जाट रक्त बह रहा है। क्योंकि केल्टिक आर्य लोग तथा जूट, एंगल, सैक्सन और डेन लोग जाटवंशज थे। आज भी वहां पर अनेक जाटगोत्रों के मनुष्य विद्यमान हैं जो कि धर्म से ईसाई हैं।

See also

External links

References

- ↑ "Sussex, Definition of Sussex from Webster's New World College Dictionary".

- ↑ Lowerson, John (1980). A Short History of Sussex. Folkestone: Dawson Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7129-0948-8.

- ↑ "1645, Latin, Map edition: Suthsexia; vernacule Sussex". National Library of Australia.

- ↑ Edwards, Heather (2004). "Ecgberht [Egbert (d. 839), king of the West Saxons in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography". Oxford University Press.]

- ↑ "BBC News - Sussex". BBC.

- ↑ "Eric Pickles: celebrate St George and England's traditional counties". Department for Communities and Local Government. 23 April 2013.

- ↑ Kelner, Simon (23 April 2013). "Eric Pickles's championing of traditional English counties is something we can all get behind". The Independent. London.

- ↑ Garber, Michael (23 April 2013). "Government 'formally acknowledges' the Historic Counties to Celebrate St George's Day". Association of British Counties.

- ↑ McGourty, Christine (23 June 2008). "'Neanderthal tools' found at dig". BBC News.

- ↑ Highfield, Roger (23 June 2008). "Neanderthal tools reveal advanced technology". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- ↑ Kerridge & Standing 2000, p. 10.

- ↑ "Prehistory: The Downs Above Steyning". Steyning Museum.

- ↑ Armstrong. A History of Sussex. Ch. 3.

- ↑ Armstrong. A History of Sussex. Ch. 3.

- ↑ Cunliffe. Iron Age communities in Britain. p. 169.

- ↑ Osprey Publishing - Military History Books - The Roman Invasion of Britain

- ↑ White, Sally; et al. (1999). "A Mid-Fifth Century Hoard of Roman and Pseudo-Roman Material from Patching, West Sussex" (PDF). Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies: 88–93

- ↑ 1. Welch. Anglo-Saxon England p.9; 2. ASC Parker MS. 477 AD.

- ↑ ASC 485 Parker MS: This year Ælle fought with the Welsh nigh Mecred's- Burnsted.

- ↑ Welch. Early Anglo-Saxon Sussex; pp. 24-25

- ↑ Welch. Early Anglo-Saxon Sussex; pp. 24-25

- ↑ 1. Bates William the Conqueror pp. 79–89; 2. Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, pp. 198–199; Orderic, vol. 2, pp. 168–171

- ↑ "Victoria County History A History of the County of Sussex: Volume 4, The Rape of Chichester".

- ↑ Seward, Desmond (1995). Sussex. London: Random House. pp. 5–7. ISBN 0-7126-5133-0.

- ↑ Seward, Desmond (1995). Sussex. London: Random House. pp. 5–7. ISBN 0-7126-5133-0.

- ↑ Brandon, Peter (2009). The Shaping of the Sussex Landscape. Snake River Press.

- ↑ Armstrong. A History of Sussex. pp. 48-58

- ↑ Kelly, S.E (1998). Anglo-Saxon Charters VI, Charters of Selsey. OUP for the British Academy. ISBN 0-19-726175-2.

- ↑ Brandon, Peter (2009). The Shaping of the Sussex Landscape. Snake River Press.

- ↑ Powicke, F. M. (1962) [1953], The Thirteenth Century: 1216-1307 (2nd ed.), Oxford: Clarendon Press

- ↑ Lowerson, John (1980). A Short History of Sussex. Folkestone: Dawson Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7129-0948-8.

- ↑ Peter Wilkinson. The Struggle for Protestant Reformation 1553-1564: in Kim Leslie's. An Historical Atlas of Sussex. pp. 52-53

- ↑ Stephens Memorials of the See of Chichester. pp. 213-214

- ↑ Stephens Memorials of the See of Chichester. pp. 213-214

- ↑ Peter Wilkinson. The Struggle for Protestant Reformation 1553-1564: in Kim Leslie's. An Historical Atlas of Sussex. pp. 52-53

- ↑ Lowerson, John (1980). A Short History of Sussex. Folkestone: Dawson Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7129-0948-8.

- ↑ 1642: Civil War in the South East".

- ↑ Brandon, Peter (2009). The Shaping of the Sussex Landscape. Snake River Press.

- ↑ Harrison. The common people. pp. 249-253

- ↑ "The Day Sussex Died".

- ↑ Kim Leslie and Marlin Mace. Sussex Defences in the Second World War in Kim Leslie. An Historical Atlas of Sussex. pp. 118-119.

- ↑ 1. Kim Leslie and Marlin Mace. Sussex Defences in the Second World War in Kim Leslie. An Historical Atlas of Sussex. pp. 118-119. 2. Brandon. Sussex. pp. 302-309.

- ↑ Brandon. Sussex. pp. 302-309.

- ↑ "Select Committee on Transport, Local Government and the Regions: Appendices to the Minutes of Evidence. Supplementary memorandum by Crawley Borough Council (NT 15(a))". United Kingdom Parliament Publications and Records website. The Information Policy Division, Office of Public Sector Information. 2002.

- ↑ Jat History Dalip Singh Ahlawat/Chapter IV, pp.399-401