Karkheh River

| Author: Laxman Burdak, IFS (R). |

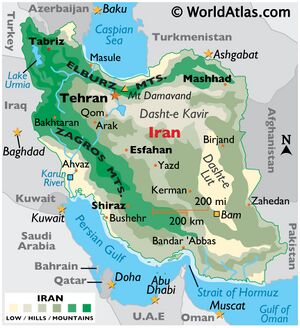

Karkheh or Karkhen is a river in Khūzestān Province Andimeshk city, Iran (ancient Susiana). It is mentioned as Choaspes by Pliny.[1]

Variants of name

- Choaspes (Anabasis by Arrian, p. 172.)

- Eulaeus River (Anabasis by Arrian, p. 107, 379, 380, 381.)

- Ulai (Anabasis by Arrian,p. 379.)

- Eulaeus River (Greek)

- Eulaeus/Eulæus (Greek)

- Eulaios

- Karkheh

- Karkhen

- Kara Su

- Gihon—one of the four rivers of Eden/Paradise to the Bible and as the Choaspes[2] in ancient times;

Jat Gotras Namesake

- Ulash = Eulaeus River = Choaspes (Pliny.vi.31)

- Ulha = Ulai (Hebrew: אולי) [4] = Choaspes (Pliny.vi.31)

- Ulash = Eulæus (Pliny.vi.26)

Jat Gotras Namesake

- Ulash = Eulaeus River = Choaspes (Anabasis by Arrian, p. 172.)

- Ulash = Eulaeus River (Anabasis by Arrian, p. 107, 379, 380, 381.)

- Ulha = Ulai (Anabasis by Arrian,p. 379.)

Mention by Pliny

Pliny[5] mentions Voyages to India.....They then arrived at the mouth of the Euphrates, and from thence passed into a lake which is formed by the rivers Eulæus18 and Tigris, in the vicinity of Charax19 after which they arrived at Susa20 on the river Tigris.

18 A river of ancient Susiana, the present name of which is Karun. Pliny states, in c. 31 of the present Book, that the Eulæus flowed round the citadel of Susa; he mistakes it, however, for the Coprates, or, more strictly speaking, for a small stream now called the Shapúr river, the ancient name of which has not been preserved. He is also in error, most probably, in making the river Eulæus flow through Messabatene, it being most likely the present Mah-Sabaden, in Laristan, which is drained by the Kerkbah, the ancient Choaspes, and not by the Eulæus.

19 Called, for the sake of distinction, Charax Spasinu, originally founded by Alexander the Great. It was afterwards destroyed by a flood, and rebuilt by Antiochus Epiphanes, under the name of Antiochia. It is mentioned in c. 31.

20 The Shushan of Scripture, now called Shu. It was the winter residence of the kings of Persia, and stood in the district Cersia of the province Susiana, on the eastern bank of the river Choaspes. The site of Sisa is now marked by extensive mounds.

Mention by Pliny

Pliny[6] mentions Tigris....After this (Pasitigris), it receives the Choaspes17, which comes from Media; and then, as we have already stated,18 flowing between Seleucia and Ctesiphon, discharges itself into the Chaldæan Lakes, which it supplies for a distance of seventy miles. Escaping from them by a vast channel, it passes the city of Charax to the right, and empties itself into the Persian Sea, being ten miles in width at the mouth.

17 A river of Susiana, which, after passing Susa, flowed into the Tigris, below its junction with the Euphrates. The indistinctness of the ancient accounts has caused it to be confused with the Eulæus, which flows nearly parallel with it into the Tigris. It is pretty clear that they were not identical. Pliny here states that they were different rivers, but makes the mistake below, of saying that Susa was situate upon the Eulæus, instead of the Choaspes. These errors may be accounted for, it has been suggested, by the fact that there are two considerable rivers which unite at Bund-i- Kir, a little above Ahwaz, and form the ancient Pasitigris or modern Karun. It is supposed that the Karun represents the ancient Eulæus, and the Kerkhah the Choaspes.

18 In c. 26 of the present Book. The custom of the Persian kings drinking only of the waters of the Eulæus and Choaspes, is mentioned in B. xxxi. c. 21.

History

The early occupation of the Euphrates basin was limited to its upper reaches; that is, the area that is popularly known as the Fertile Crescent. Acheulean stone artifacts have been found in the Sajur basin and in the El Kowm oasis in the central Syrian steppe; the latter together with remains of Homo erectus that were dated to 450,000 years old.[7][8]

In the Taurus Mountains and the upper part of the Syrian Euphrates valley, early permanent villages such as Abu Hureyra – at first occupied by hunter-gatherers but later by some of the earliest farmers, Jerf el-Ahmar, Mureybet and Nevalı Çori became established from the eleventh millennium BCE onward.[9]

In the absence of irrigation, these early farming communities were limited to areas where rainfed agriculture was possible, that is, the upper parts of the Syrian Euphrates as well as Turkey.[10] Late Neolithic villages, characterized by the introduction of pottery in the early 7th millennium BCE, are known throughout this area.[11]

Occupation of lower Mesopotamia started in the 6th millennium and is generally associated with the introduction of irrigation, as rainfall in this area is insufficient for dry agriculture. Evidence for irrigation has been found at several sites dating to this period, including Tell es-Sawwan.[12]

During the 5th millennium BCE, or late Ubaid period, northeastern Syria was dotted by small villages, although some of them grew to a size of over 10 hectares (25 acres).[13]

In Iraq, sites like Eridu and Ur were already occupied during the Ubaid period.[14]

Clay boat models found at Tell Mashnaqa along the Khabur indicate that riverine transport was already practiced during this period.[15] The Uruk period, roughly coinciding with the 4th millennium BCE, saw the emergence of truly urban settlements across Mesopotamia. Cities like Tell Brak and Uruk grew to over 100 hectares (250 acres) in size and displayed monumental architecture.[16]

The spread of southern Mesopotamian pottery, architecture and sealings far into Turkey and Iran has generally been interpreted as the material reflection of a widespread trade system aimed at providing the Mesopotamian cities with raw materials. Habuba Kabira on the Syrian Euphrates is a prominent example of a settlement that is interpreted as an Uruk colony.[17][18]

During the Jemdet Nasr and Early Dynastic periods (3100–2350 BCE), southern Mesopotamia experienced a growth in the number and size of settlements, suggesting strong population growth. These settlements, including sites like Sippar, Uruk and Kish, were organized in competing city-states.[19]

Many of these cities were located along canals of the Euphrates and the Tigris that have since dried up, but that can still be identified from remote sensing imagery.[20]

A similar development took place in Upper Mesopotamia, although only in the second part of the 3rd millennium and on a smaller scale than in Lower Mesopotamia. Sites like Mari and Tell Leilan grew to prominence for the first time during this period.[21]

Large parts of the Euphrates basin were for the first time united under a single ruler during the Akkadian and Ur III empires, which controlled – either directly or indirectly through vassals – large parts of modern-day Iraq and northeastern Syria.[22]

Following their collapse, Mari asserted its power over northeast Syria while southern Mesopotamia was controlled by city-states like Isin and Larsa before their territories were absorbed by Babylon under Hammurabi in the 18th century BCE.[23]

In the second half of the 2nd millennium BCE, the Euphrates basin was divided between Kassite Babylon in the south and Mitanni in the north, with the latter being eventually replaced by Assyria and the Hittite Empire.[24]

Following the collapse of the Hittite Empire and the reduction in power of Assyria and Babylonia during the 12th century BCE, struggles broke out between Babylonia and Assyria over the control of the Iraqi Euphrates basin. The Neo-Assyrian Empire eventually emerged victorious out of this conflict and also succeeded in gaining control of the northern Euphrates basin in the first half of the 1st millennium BCE.[25]

In the centuries to come, control of the wider Euphrates basin shifted from the Neo-Assyrian Empire to the Neo-Babylonian Empire in the 7th century and to the Achaemenids in the 6th century BCE.[26]

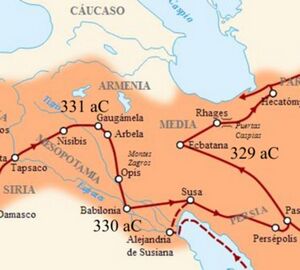

The Achaemenid Empire was in turn overrun by Alexander the Great, who defeated the last king Darius III and died in Babylon in 323 BCE.[27]

For several centuries, the river formed the eastern limit of effective Egyptian and Roman control and western regions of the Persian Empire.

सुप्रात

सुप्रात (AS, p.975): मेसोपोटामिया की फ़रात नदी का संस्कृत नाम [28]

Ch 7.21 Description of the Euphrates and the Pallacopas by Arrian

Arrian[29] writes.... While the triremes were being built for him, and the harbour near Babylon was being excavated, Alexander sailed from Babylon down the Euphrates to what was called the river Pallacopas, which is distant from Babylon about 800 stades.[1] This Pallacopas is not a river rising from springs, but a canal cut from the Euphrates. For that river flowing from the Armenian mountains,[2] proceeds within its banks in the season of winter, because its water is scanty; bub when the spring begins to make its appearance, and especially just before the summer solstice, it pours along with mighty stream and overflows its banks into the Assyrian country.[3] For at that season the snow upon the Armenian mountains melts and swells its water to a great degree; and as its stream flows high above the level of the country, it would flow over the land if some one had not furnished it with an outlet along the Pallacopas and turned it aside into the marshes and pools, which, beginning from this canal, extend as far as the country contiguous to Arabia. Thence it spreads out far and wide into a shallow lake, from which it falls into the sea by many invisible mouths. After the snow has melted, about the time of the setting of the Pleiades, the Euphrates flows with a small stream; but none the less the greater part of it discharges itself into the pools along the Pallacopas. Unless, therefore, some one had dammed up the Pallacopas again, so that the water might be turned back within the banks and carried down the channel of the river, it would have drained the Euphrates into itself, and consequently the Assyrian country would not be watered by it. But the outlet of the Euphrates into the Pallacopas was dammed up by the viceroy of Babylonia with great labour (although it was an easy matter to construct the outlet), because the ground in this region is slimy and most of it mud, so that when it has once received the water of the river it is not easy to turn it back. But more than 10,000 Assyrians were engaged in this labour even until the third month. When Alexander was informed of this, he was induced to confer a benefit upon the land of Assyria. He determined to shut up the outlet where the stream of the Euphrates was turned into the Pallacopas. When he had advanced about thirty stades, the earth appeared to be somewhat rocky, so that if it were cut through and a junction made with the old canal along the Pallacopas, on account of the hardness of the soil, it would not allow the water to percolate, and there would be no difficulty in turning it back at the appointed season. For this purpose he sailed to the Pallacopas, and then continued his voyage down that canal into the pools towards the country of the Arabs. There seeing a certain admirable site, he founded a city upon it and fortified it. In it he settled as many of the Grecian mercenaries as volunteered to remain, and such as were unfit for military service by reason of age or wounds.

1. About 90 miles. This canal fell into the Persian Gulf at Teredon. No trace of it now remains.

2. The Hebrew name for Armenia is Ararat (2 Kings xix. 37; Isa. xxxYii. 38; Jer. li. 27).

3. The country called Assyria by the Greeks is called Asshur (level) in Hebrew. In Gen. x. 11 the foundation of the Assyrian kingdom is ascribed to Nimrod; for the verse ought to be translated: "He went forth from that land into Asshur." Hence in Micah v. 6, Assyria is called the "land of Nimrod."

References

- ↑ Natural History by Pliny Book VI/Chapter 31

- ↑ Bosworth, A. B. (1993). Conquest and Empire: The Reign of Alexander the Great. Cambridge University Press. p. 88. ISBN 0-521-40679-X.

- ↑ Potts, Daniel T. (1999). The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State. Cambridge University Press. p. 236. ISBN 0-521-56496-4. "One refers to his camp while on campaign and to action near the Ulai, the modern Karkheh river, in Khuzistan"

- ↑ Potts, Daniel T. (1999). The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State. Cambridge University Press. p. 236. ISBN 0-521-56496-4. "One refers to his camp while on campaign and to action near the Ulai, the modern Karkheh river, in Khuzistan"

- ↑ Natural History by Pliny Book VI/Chapter 26

- ↑ Natural History by Pliny Book VI/Chapter 31

- ↑ Muhesen, Sultan (2002), "The Earliest Paleolithic Occupation in Syria", in Akazawa, Takeru; Aoki, Kenichi; Bar-Yosef, Ofer, Neandertals and Modern Humans in Western Asia, New York: Kluwer, pp. 95–105, doi:10.1007/0-306-47153-1_7

- ↑ Schmid, P.; Rentzel, Ph.; Renault-Miskovsky, J.; Muhesen, Sultan; Morel, Ph.; Le Tensorer, Jean Marie; Jagher, R. (1997), "Découvertes de Restes Humains dans les Niveaux Acheuléens de Nadaouiyeh Aïn Askar (El Kowm, Syrie Centrale)", Paléorient 23 (1): 87–93, doi:10.3406/paleo.1997.4646

- ↑ Sagona, Antonio; Zimansky, Paul (2009), Ancient Turkey, Routledge World Archaeology, London: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-48123-6

- ↑ Akkermans, Peter M. M. G.; Schwartz, Glenn M. (2003), The Archaeology of Syria. From Complex Hunter-Gatherers to Early Urban Societies (ca. 16,000-300 BC), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-79666-0

- ↑ Akkermans, Peter M. M. G.; Schwartz, Glenn M. (2003), The Archaeology of Syria. From Complex Hunter-Gatherers to Early Urban Societies (ca. 16,000-300 BC), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-79666-0

- ↑ Helbaek, Hans (1972), "Samarran Irrigation Agriculture at Choga Mami in Iraq", Iraq 34 (1): 35–48, doi:10.2307/4199929

- ↑ Akkermans, Peter M. M. G.; Schwartz, Glenn M. (2003), The Archaeology of Syria. From Complex Hunter-Gatherers to Early Urban Societies (ca. 16,000-300 BC), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-79666-0

- ↑ Oates, Joan (1960), "Ur and Eridu, the Prehistory", Iraq 22: 32–50, doi:10.2307/4199667

- ↑ Akkermans, Peter M. M. G.; Schwartz, Glenn M. (2003), The Archaeology of Syria. From Complex Hunter-Gatherers to Early Urban Societies (ca. 16,000-300 BC), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-79666-0,pp.167-168

- ↑ Ur, Jason A.; Karsgaard, Philip; Oates, Joan (2007), "Early Urban Development in the Near East", Science 317 (5842): 1188, doi:10.1126/science.1138728

- ↑ Akkermans & Schwartz 2003, p. 203

- ↑ van de Mieroop, Marc (2007), A History of the Ancient Near East, ca. 3000–323 BC. Second Edition, Blackwell History of the Ancient World, Malden: Blackwell, ISBN 978-1-4051-4911-2,pp.38–39

- ↑ Adams, Robert McC. (1981), Heartland of Cities. Surveys of Ancient Settlement and Land Use on the Central Floodplain of the Euphrates, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-00544-5

- ↑ Hritz, Carrie; Wilkinson, T.J. (2006), "Using Shuttle Radar Topography to Map Ancient Water Channels in Mesopotamia", Antiquity 80: 415–424, ISSN 0003-598X

- ↑ Akkermans & Schwartz 2003, p. 233

- ↑ van de Mieroop 2007, p. 63

- ↑ van de Mieroop 2007, p. 111

- ↑ van de Mieroop 2007, p. 132

- ↑ van de Mieroop 2007, p. 241

- ↑ van de Mieroop 2007, p. 270

- ↑ van de Mieroop 2007, p. 287

- ↑ Aitihasik Sthanavali by Vijayendra Kumar Mathur, p.975

- ↑ The Anabasis of Alexander/7b, Ch.21

Location

It rises in the Zagros Mountains, and passes west of Shush (ancient Susa), eventually falling in ancient times into the Tigris just below its confluence with the Euphrates very near to the Iran-Iraq border. The river is currently the location of the Karkheh Dam and hydro-power plant in Iran.

Course

In modern times, after approaching within 16 kilometres of the Dez River, it turns to the southwest and then, northwest of Ahvaz, turns northwest and is absorbed by the Hawizeh Marshes that straddle the Iran–Iraq border. Its peculiarly sweet water was sacred to the use of the Persian kings.[1] Ancient names for the Karkheh should be treated as conjectural because the bed of the river has changed in historic times, and because a nearby watercourse between the Karkheh and the Dez River, the Shaur, confuses the identification.[2]

The problem with the ancient names is that while the Karkheh flows a kilometre or two west of Susa, another major watercourse flows parallel to the Karkheh within a few kilometres east of Susa. When these rivers are in flood stage, the entire area south of Susa can be flooded, as the waters of the two watercourses mingle. The watercourse a kilometre or two east of Susa, now called the Shaur, flows east between the Haft Tepe and Shaur ridges into the Dez River, north of where the Dez and Karun rivers merge. At some previous time, the Karkheh may have joined the eastern end of the Shaur. The timing of these changes is not known with any certainty. The ancient name of the Shaur may have been the Choaspes.

The river is mentioned in the Bible, Book of Daniel 8:2,16, and should not be confused with the Choaspes River in modern-day Afghanistan, which flows into the Indus.

Arrian[3] writes....Alexander now ordered Hephaestion to lead the main body of the infantry as far as the Persian Sea, while he himself, his fleet having sailed up into the land of Susiana, embarked, with the shield-bearing guards and the body-guard of infantry; and having also put on board a few of the cavalry Companions, he sailed down the river Eulaeus to the sea.[1] When he was near the place where the river discharges itself into the deep, he left there most of his ships, including those which were in need of repair, and with those especially adapted for fast sailing he coasted along out of the river Eulaeus through the sea to the mouth of the Tigres. The rest of the ships were conveyed down the Eulaeus as far as the canal which has been cut from the Tigres into the Eulaeus, and by this means they were brought into the Tigres. Of the rivers Euphrates and Tigres which enclose Syria between them, whence also its name is called by the natives Mesopotamia,[2] the Tigres flows in a much lower channel than the Euphrates, from which it receives many canals; and after taking up many tributaries and its waters being swelled by them, it falls into the Persian Sea.[3] It is a large river and can be crossed on foot nowhere as far as its mouth,[4] inasmuch as none of its water is used up by irrigation of the country. For the land through which it flows is more elevated than its water, and it is not drawn off into canals or into another river, but rather receives them into itself. It is nowhere possible to irrigate the land from it. But the Euphrates flows in an elevated channel, and is everywhere on a level with the land through which it passes. Many canals have been made from it, some of which are always kept flowing, and from which the inhabitants on both banks supply themselves with water; others the people make only when requisite to irrigate the land, when they are in need of water from drought.[5] For this country is usually free from rain. The consequence is, that the Euphrates at last has only a small volume of water, which disappears into a marsh. Alexander sailed over the sea round the shore of the Persian Gulf lying between the rivers Eulaeus and Tigres; and thence he sailed up the latter river as far as the camp where Hephaestion had settled with all his forces. Thence he sailed again to Opis, a city situated on that river.[6] In his voyage up he destroyed the weirs which existed in the river, and thus made the stream quite level. These weira had been constructed by the Persians, to prevent any enemy having a superior naval force from sailing up from the sea into their country. The Persians had had recourse to these contrivances because they were not a nautical people; and thus by making an unbroken succession of weirs they had rendered the voyage up the Tigres a matter of impossibility. But Alexander said that such devices were unbecoming to men who are victorious in battle; and therefore he considered this means of safety unsuitable for him; and by easily demolishing the laborious work of the Persians, he proved in fact that what they thought a protection was unworthy of the name.

1. The Eulaeus is now called Kara Su. After joining the Ooprates it was called Pasitigris. It formerly discharged itself into the Persian Gulf, but now into the Shat-el-Arab, as the united stream of the Euphrates and Tigris is now called. In Dan. viii. 2, 16, it is called Ulai. Cf. Pliny, vi. 26, 31; xxxi. 21.

2. The Greeks and Romans sometimes speak of Mesopotamia as a part of Syria, and at other times they call it a part of Assyria. The Hebrew and native name of this country was Aram Naharaim, or "Syria of the two rivers."

3. The Tigris now falls into the Euphrates.

4. Cf. Arrian, iii. 7, supra; Curtius, iv. 37.

5. Cf. Strabo, xvi. 1; Herodotus, i, 193; Ammianus, xxiv. 3, 14.

6. Probably this city stood at the junction of the Tigris with the Physcus, or Odoneh. See Xenophon (Anab. ii. 4, 26); Herodotus, i. 189; Strabo, (xvi. 1) says that Alexander made the Tigris navigable up to Opis.

References

- ↑ Hazlitt, William (1851). "page 108". The Classical Gazetteer. Archived from the original on 2007-03-03.

- ↑ John Hansman, "Charax and the Karkheh," Iranica Antiqua VII(1967), pp.21-58, and Michael J. Kirkby, "Land and Water Resources of the Deh Luran and Khuzistan Plains," Appendix I, in Studies in the Archaeological History of the Deh Luran Plain. The Excavation of Chagha Sefid, edited by Frank Hole, pp. 251-288. Memoirs, no. 9, Ann Arbor, Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan

- ↑ The Anabasis of Alexander/7a, Ch.7