Varangians

| Author:Laxman Burdak, IFS (R) |

Varangians (वरैंजियाई) was the name given by Eastern Romans to Vikings,[1] conquerors, traders and settlers, mostly from Sweden.[2][3]

Variants

- /vəˈrændʒiənz/;

- Old Norse: Væringjar;

- Medieval Greek: Βάραγγοι, Várangoi;[4][5]

- Old East Slavic: варяже, varyazhe or варязи, varyazi,

- Russian: варяги,

- English: Varangians or Varyags

Etymology

Medieval Greek Βάραγγος Várangos and Old East Slavic варягъ varjagŭ (Old Church Slavonic варѧгъ varęgŭ) are derived from Old Norse væringi, originally a compound of vár 'pledge' or 'faith', and gengi 'companion', thus meaning 'sworn companion', 'confederate', extended to mean 'a foreigner who has taken service with a new lord by a treaty of fealty to him', or 'protégé'.[6][7] Some scholars seem to assume a derivation from vár with the common suffix -ing.[8] Yet, this suffix is inflected differently in Old Norse, and furthermore, the word is attested with -gangia and cognates in other Germanic languages in the Early Middle Ages, as in Old English wærgenga, Old Frankish wargengus and Langobardic waregang.[9] The reduction of the second part of the word could be parallel to that seen in Old Norse foringi 'leader', correspondent to Old English foregenga and Gothic 𐍆𐌰𐌿𐍂𐌰𐌲𐌰𐌲𐌲𐌾𐌰 fauragaggja 'steward'.[10][11]

Jat clans

History

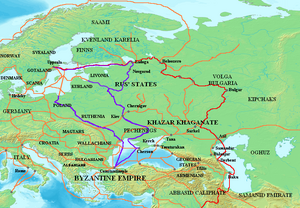

Between the 9th and 11th centuries, Varangians ruled the medieval state of Kievan Rus', settled among many territories of modern Belarus, Russia and Ukraine, and formed the Byzantine Varangian Guard which later also included Anglo-Saxons.[12][13]

According to the 12th-century Kievan Primary Chronicle, a group of Varangians known as the Rus'[14] settled in Novgorod in 862 under the leadership of Rurik. Before Rurik, the Rus' might have ruled an earlier hypothetical polity named Rus' Khaganate. Rurik's relative Oleg conquered Kiev in 882 and established the state of Kievan Rus', which was later ruled by Rurik's descendants.[15][16]

Engaging in trade, piracy, and mercenary service, Varangians roamed the river systems and portages of Gardariki, as the areas north of the Black Sea were known in the Norse sagas. They controlled the Volga trade route (between the Varangians and the Muslims), connecting the Baltic to the Caspian Sea and the Dnieper and Dniester trade route (between Varangians and the Greeks) leading to the Black Sea and Constantinople.[17] Those were the main important trade links at that time, connecting Medieval Europe with Abbasid Caliphates and the Byzantine Empire.[18]Most of the silver coinage in the West came from the East via those routes.

Attracted by the riches of Constantinople, the Varangian Rus' began the Rus'-Byzantine Wars, some of which resulted in advantageous trade treaties. At least from the early 10th century, many Varangians served as mercenaries in the Byzantine Army, constituting the elite Varangian Guard (the bodyguards of Byzantine emperors). Eventually most of them, in Byzantium and in Eastern Europe, were converted from Norse paganism to Orthodox Christianity, culminating in the Christianization of Kievan Rus' in 988. Coinciding with the general decline of the Viking Age, the influx of Scandinavians to Rus' stopped and Varangians were gradually assimilated by East Slavs by the late 11th century.

वरैंजियाई

वरैंजियाई या वारयागी पूर्वी स्लाव लोगों और यूनानियों द्वारा उन वाइकिंग लोगों के लिए इस्तेमाल होने वाला एक नाम था जिन्होंने 9वीं से 11वीं सदी ईसवी तक मध्यकालीन कीवयाई रूस राज्य पर राज किया और जिनसे बीज़ान्टिन सल्तनत का वरैन्जियाई दस्ता बना हुआ था। 12वीं सदी में लिखे गए प्रमुख वृत्तांत नामक इतिहास-गाथा में दर्ज है कि वरैन्जियाईयों का एक गुट रूरिक (Rurik, Рюрик) नामक शासक के नेतृत्व में 862 ईसवी में नोवगोरोद क्षेत्र में आकर बस गया। 882 में रूरिक के सम्बन्धी ओलेग (Oleg, Олег) ने कीव पर चढ़ाई करी और क़ब्ज़ा कर के उसे कीवयाई रूस का आधार बनाया। इस राज्य पर बाद में रूरिक के वंशजों ने शासन किया और यही रूस, बेलारूस और युक्रेन का ऐतिहासिक आधार माना जाता है।

See also

External links

References

- ↑ Ildar Kh. Garipzanov, The Annals of St. Bertin (839) and Chacanus of the Rhos. Ruthenica 5 (2006) 3–8 sides with the old theory.

- ↑ "Oleg". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ "Rus | people | Britannica". www.britannica.com.

- ↑ "Varangian," Online Etymology Dictionary

- ↑ "Varangian". TheFreeDictionary.com.

- ↑ "Varangian," Online Etymology Dictionary

- ↑ H.S. Falk & A. Torp, Norwegisch-Dänisches Etymologisches Wörterbuch, 1911, pp. 1403–04; J. de Vries, Altnordisches Etymologisches Wörterbuch, 1962, pp. 671–72; S. Blöndal & B. Benedikz, The Varangians of Byzantium, 1978, p. 4

- ↑ Hellquist 1922:1096, 1172; M. Vasmer, Russisches etymologisches Wörterbuch, 1953, vol. 1, p. 171.

- ↑ Blöndal & Benedikz, p. 4; D. Parducci, "Gli stran

- ↑ Falk & Torp, p. 1403; other words with the same second part are: Old Norse erfingi 'heir', armingi or aumingi 'beggar", bandingi 'captive', hamingja 'luck', heiðingi 'wolf', lausingi or leysingi 'homeless'; cf. Falk & Torp, p. 34; Vries, p. 163.

- ↑ Bugge, Sophus, Arkiv för nordisk filologi 2 (1885), p. 225

- ↑ Milner-Gulland, R. R. (1989). Atlas of Russia and the Soviet Union. Phaidon. p. 36. ISBN 0-7148-2549-2.

- ↑ Milner-Gulland, R. R. (1989). Atlas of Russia and the Soviet Union. Phaidon. p. 36. ISBN 0-7148-2549-2.

- ↑ "Пушкинский Дом (ИРЛИ РАН) > Новости".

- ↑ Duczko, Wladyslaw (2004). Viking Rus. Brill Publishers. pp. 10–11. ISBN 90-04-13874-9.

- ↑ "Rurik Dynasty". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ Stephen Turnbull, The Walls of Constantinople, AD 324–1453, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 1-84176-759-X.

- ↑ Schofield, Tracey Ann Vikings, Lorenz Educational Press, p. 7, ISBN 978-1-5731-0356-5