Anglo-Saxons

| Author:Laxman Burdak, IFS (R) |

Anglo-Saxons (एंग्लो सैक्सन्स) were Germanic tribes that settled in Britain and founded England. Throughout this article Anglo-Saxon is used for Saxon, Angle, Jute or Frisian unless it is specific to a point being made; "Anglo-Saxon" is used when the culture is meant as opposed to any ethnicity. Jutes in England merged with the Angles and Saxons to form the new ethnolinguistic group of the Anglo-Saxons.

Terminology

Bede completed his book Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum (Ecclesiastical History of the English People) in around 731. Thus, the term for English people (Latin: gens Anglorum; Old English: Angelcynn) was in use by then to distinguish Germanic groups in Britain from those on the continent (Old Saxony in Northern Germany).[1]The term 'Anglo-Saxon' came into use in the 8th century (probably by Paul the Deacon) to distinguish English Saxons from continental Saxons (Ealdseaxan, 'old' Saxons).

The historian James Campbell suggested that it was not until the late Anglo-Saxon period that England could be described as a nation state.[2]It is certain that the concept of "Englishness" only developed very slowly.[3]

Anglo Saxon Clans

Here is a partial list of Anglo-Saxon Clans and phonetically similar Jat clans

- Bucca - In the 7th century, Buckingham, literally meadow of Bucca's people is said to have been founded by Bucca, the leader of the first Anglo Saxon settlers.[4] Jat clan - Bakaiya, Bukan

- Beorma: The name Birmingham comes from the Old English Beormingahām,[5] meaning the home or settlement of the Beormingas – a tribe or clan whose name literally means 'Beorma's people' and which may have formed an early unit of Anglo-Saxon administration.[6] Beorma, after whom the tribe was named, could have been its leader at the time of the Anglo-Saxon settlement, a shared ancestor, or a mythical tribal figurehead. Jat clan - Birhman

- Billungs - The House of Billung was a dynasty of Saxon noblemen in the 9th through 12th centuries. The territory of the Free State of Saxony became part of the Holy Roman Empire by the 10th century, when the dukes of Saxony were also kings (or emperors) of the Holy Roman Empire, comprising the Ottonian, or Saxon, Dynasty. Around this time, the Billungs, a Saxon noble family, received extensive lands in Saxony. The emperor eventually gave them the title of dukes of Saxony. After Duke Magnus died in 1106, causing the extinction of the male line of Billungs, oversight of the duchy was given to Lothar of Supplinburg, who also became emperor for a short time. Jat clan - Biling

History

Anglo-Saxon England or Early Medieval England, existing from the 5th to the 11th centuries from the end of Roman Britain until the Norman conquest in 1066, consisted of various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms until 927, when it was united as the Kingdom of England by King Æthelstan (r. 927–939). It became part of the short-lived North Sea Empire of Cnut the Great, a personal union between England, Denmark and Norway in the 11th century.

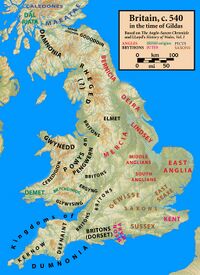

The Anglo-Saxons were the members of Germanic-speaking groups who migrated to England from nearby mainland northwestern Europe. Anglo-Saxon history thus begins during the period of sub-Roman Britain following the end of Roman control, and traces the establishment of Anglo-Saxon kingdoms in the 5th and 6th centuries (conventionally identified as seven main kingdoms: Northumbria, Mercia, East Anglia, Essex, Kent, Sussex, and Wessex); their Christianisation during the 7th century; the threat of Viking invasions and Danish settlers; the gradual unification of England under the Wessex hegemony during the 9th and 10th centuries; and ending with the Norman conquest of England by William the Conqueror in 1066.

Anglo-Saxon identity survived beyond the Norman conquest,[7] came to be known as Englishry under Norman rule, and through social and cultural integration with Celts, Danes and Normans became the modern English people.

As the Roman occupation of Britain was coming to an end, Constantine III withdrew the remains of the army in reaction to the Germanic invasion of Gaul with the Crossing of the Rhine in December 406.[8][6] The Romano-British leaders were faced with an increasing security problem from seaborne raids, particularly by Picts on the east coast of England.[9] The expedient adopted by the Romano-British leaders was to enlist the help of Anglo-Saxon mercenaries (known as foederati), to whom they ceded territory.[10] In about 442 the Anglo-Saxons mutinied, apparently because they had not been paid.[11] The Romano-British responded by appealing to the Roman commander of the Western empire, Aëtius, for help (a document known as the Groans of the Britons), even though Honorius, the Western Roman Emperor, had written to the British civitas in or about 410 telling them to look to their own defence.[12] There then followed several years of fighting between the British and the Anglo-Saxons.[13] The fighting continued until around 500, when, at the Battle of Mount Badon, the Britons inflicted a severe defeat on the Anglo-Saxons.[14]

Migration and the formation of kingdoms (400–600)

There are records of Germanic infiltration into Britain that date before the collapse of the Roman Empire.[15] It is believed that the earliest Germanic visitors were eight cohorts of Batavians attached to the 14th Legion in the original invasion force under Aulus Plautius in AD 43.[16][17] There is a recent hypothesis that some of the native tribes, identified as Britons by the Romans, may have been Germanic-language speakers, but most scholars disagree with this due to an insufficient record of local languages in Roman-period artefacts.[18]

It was quite common for Rome to swell its legions with foederati recruited from the German homelands.[19] This practice also extended to the army serving in Britain, and graves of these mercenaries, along with their families, can be identified in the Roman cemeteries of the period.[20] The migration continued with the departure of the Roman army, when Anglo-Saxons were recruited to defend Britain; and also during the period of the Anglo-Saxon first rebellion of 442.[21]

If the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is to be believed, the various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms which eventually merged to become England were founded when small fleets of three or five ships of invaders arrived at various points around the coast of England to fight the sub-Roman British, and conquered their lands.[22] The language of the migrants, Old English, came over the next few centuries to predominate throughout what is now England, at the expense of British Celtic and British Latin.

The arrival of the Anglo-Saxons into Britain can be seen in the context of a general movement of Germanic peoples around Europe between the years 300 and 700, known as the Migration period (also called the Barbarian Invasions or Völkerwanderung). In the same period there were migrations of Britons to the Armorican peninsula (Brittany and Normandy in modern-day France): initially around 383 during Roman rule, but also c. 460 and in the 540s and 550s; the 460s migration is thought to be a reaction to the fighting during the Anglo-Saxon mutiny between about 450 to 500, as was the migration to Britonia (modern day Galicia, in northwest Spain) at about the same time.[23]

The historian Peter Hunter-Blair expounded what is now regarded as the traditional view of the Anglo-Saxon arrival in Britain.[24]He suggested a mass immigration, with the incomers fighting and driving the sub-Roman Britons off their land and into the western extremities of the islands, and into the Breton and Iberian peninsulas.[25] This view is based on sources such as Bede, who mentions the Britons being slaughtered or going into "perpetual servitude".[26] According to Härke the more modern view is of co-existence between the British and the Anglo-Saxons.[27] [28]He suggests that several modern archaeologists have now re-assessed the traditional model, and have developed a co-existence model largely based on the Laws of Ine. The laws include several clauses that provide six different wergild levels for the Britons, of which four are below that of freeman.[33] Although it was possible for the Britons to be rich freemen in Anglo-Saxon society, generally it seems that they had a lower status than that of the Anglo-Saxons.[29]

Discussions and analysis still continue on the size of the migration, and whether it was a small elite band of Anglo-Saxons who came in and took over the running of the country, or a mass migration of peoples who overwhelmed the Britons.[30] An emerging view is that two scenarios could have co-occurred, with large-scale migration and demographic change in the core areas of the settlement and elite dominance in peripheral regions.[31]

According to Gildas, initial vigorous British resistance was led by a man called Ambrosius Aurelianus,[32] from which time victory fluctuated between the two peoples. Gildas records a "final" victory of the Britons at the Battle of Mount Badon in c. 500, and this might mark a point at which Anglo-Saxon migration was temporarily stemmed.[33] Gildas said that this battle was "forty-four years and one month" after the arrival of the Saxons, and was also the year of his birth.[34] He said that a time of great prosperity followed.[35] But, despite the lull, the Anglo-Saxons took control of Sussex, Kent, East Anglia and part of Yorkshire; while the West Saxons founded a kingdom in Hampshire under the leadership of Cerdic, around 520.[36] However, it was to be 50 years before the Anglo-Saxons began further major advances.[37] In the intervening years the Britons exhausted themselves with civil war, internal disputes, and general unrest, which was the inspiration behind Gildas's book De Excidio Britanniae (The Ruin of Britain).[38]

The next major campaign against the Britons was in 577, led by Ceawlin, king of Wessex, whose campaigns succeeded in taking Cirencester, Gloucester and Bath (known as the Battle of Dyrham).[39][40][41]This expansion of Wessex ended abruptly when the Anglo-Saxons started fighting among themselves and resulted in Ceawlin retreating to his original territory. He was then replaced by Ceol (who was possibly his nephew). Ceawlin was killed the following year, but the annals do not specify by whom.[42][43] Cirencester subsequently became an Anglo-Saxon kingdom under the overlordship of the Mercians, rather than Wessex.[44]

Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy Kingdoms (7th and 8th centuries)

By 600, a new order was developing, of kingdoms and sub-Kingdoms. The medieval historian Henry of Huntingdon conceived the idea of the Heptarchy, which consisted of the seven principal Anglo-Saxon kingdoms (Heptarchy literal translation from the Greek: hept – seven; archy – rule).[45]

By convention, the Heptarchy period lasted from the end of Roman rule in Britain in the 5th century, until most of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms came under the overlordship of Egbert of Wessex in 829. This approximately 400-year period of European history is often referred to as the Early Middle Ages or, more controversially, as the Dark Ages. Although heptarchy suggests the existence of seven kingdoms, the term is just used as a label of convenience and does not imply the existence of a clear-cut or stable group of seven kingdoms. The number of kingdoms and sub-kingdoms fluctuated rapidly during this period as competing kings contended for supremacy.[46] Anglo-Saxon England heptarchy

The four main kingdoms in Anglo-Saxon England were:

- East Anglia

- Mercia

- Northumbria, including sub-kingdoms Bernicia and Deira

- Wessex

Minor kingdoms:

Other minor kingdoms and territories

- Haestingas

- Hwicce

- Kingdom of the Iclingas, a precursor state to Mercia

- Isle of Wight, (Wihtwara)

- Lindsey

- Magonsæte

- Meonwara, the Meon Valley area of Hampshire

- Pecsæte

- Surrey

- Tomsæte

- Wreocensæte

At the end of the 6th century the most powerful ruler in England was Æthelberht of Kent, whose lands extended north to the River Humber.[47] In the early years of the 7th century, Kent and East Anglia were the leading English kingdoms.[48] After the death of Æthelberht in 616, Rædwald of East Anglia became the most powerful leader south of the Humber.[49]

Following the death of Æthelfrith of Northumbria, Rædwald provided military assistance to the Deiran Edwin in his struggle to take over the two dynasties of Deira and Bernicia in the unified kingdom of Northumbria.] Upon the death of Rædwald, Edwin was able to pursue a grand plan to expand Northumbrian power.[50]

The growing strength of Edwin of Northumbria forced the Anglo-Saxon Mercians under Penda into an alliance with the Welsh King Cadwallon ap Cadfan of Gwynedd, and together they invaded Edwin's lands and defeated and killed him at the Battle of Hatfield Chase in 633.[51][52]Their success was short-lived, as Oswald (one of the sons of the late King of Northumbria, Æthelfrith) defeated and killed Cadwallon at Heavenfield near Hexham.[53] In less than a decade Penda again waged war against Northumbria, and killed Oswald in the Battle of Maserfield in 642.[54]

His brother Oswiu was chased to the northern extremes of his kingdom.[55][56] However, Oswiu killed Penda shortly after, and Mercia spent the rest of the 7th and all of the 8th century fighting the kingdom of Powys.[57] The war reached its climax during the reign of Offa of Mercia,[58] who is remembered for the construction of a 150-mile-long dyke which formed the Wales/England border.[59] It is not clear whether this was a boundary line or a defensive position.[60] The ascendency of the Mercians came to an end in 825, when they were soundly beaten under Beornwulf at the Battle of Ellendun by Egbert of Wessex.[61]

Viking challenge and the rise of Wessex (9th century)

Between the 8th and 11th centuries, raiders and colonists from Scandinavia, mainly Danish and Norwegian, plundered western Europe, including the British Isles.[62] These raiders came to be known as the Vikings; the name is believed to derive from Scandinavia, where the Vikings originated.[63][64] The first raids in the British Isles were in the late 8th century, mainly on churches and monasteries (which were seen as centres of wealth).[65][66] The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reports that the holy island of Lindisfarne was sacked in 793.[67] The raiding then virtually stopped for around 40 years; but in about 835, it started becoming more regular.[68]

In the 860s, instead of raids, the Danes mounted a full-scale invasion. In 865, an enlarged army arrived that the Anglo-Saxons described as the Great Heathen Army. This was reinforced in 871 by the Great Summer Army.[69] Within ten years nearly all of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms fell to the invaders: Northumbria in 867, East Anglia in 869, and nearly all of Mercia in 874–77.[70]Kingdoms, centres of learning, archives, and churches all fell before the onslaught from the invading Danes. Only the Kingdom of Wessex was able to survive.[71] In March 878, the Anglo-Saxon King of Wessex, Alfred, with a few men, built a fortress at Athelney, hidden deep in the marshes of Somerset.[72]He used this as a base from which to harry the Vikings. In May 878 he put together an army formed from the populations of Somerset, Wiltshire, and Hampshire, which defeated the Viking army in the Battle of Edington.[73] The Vikings retreated to their stronghold, and Alfred laid siege to it.[96] Ultimately the Danes capitulated, and their leader Guthrum agreed to withdraw from Wessex and to be baptised. The formal ceremony was completed a few days later at Wedmore.[74][75] There followed a peace treaty between Alfred and Guthrum, which had a variety of provisions, including defining the boundaries of the area to be ruled by the Danes (which became known as the Danelaw) and those of Wessex.[76] The Kingdom of Wessex controlled part of the Midlands and the whole of the South (apart from Cornwall, which was still held by the Britons), while the Danes held East Anglia and the North.[77]

After the victory at Edington and resultant peace treaty, Alfred set about transforming his Kingdom of Wessex into a society on a full-time war footing.[78]He built a navy, reorganised the army, and set up a system of fortified towns known as burhs. He mainly used old Roman cities for his burhs, as he was able to rebuild and reinforce their existing fortifications.[79] To maintain the burhs, and the standing army, he set up a taxation system known as the Burghal Hidage.[80] These burhs (or burghs) operated as defensive structures. The Vikings were thereafter unable to cross large sections of Wessex: the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reports that a Danish raiding party was defeated when it tried to attack the burh of Chichester.[81][82]

Although the burhs were primarily designed as defensive structures, they were also commercial centres, attracting traders and markets to a safe haven, and they provided a safe place for the king's moneyers and mints.[83] A new wave of Danish invasions commenced in 891,[84] beginning a war that lasted over three years.[85] Alfred's new system of defence worked, however, and ultimately it wore the Danes down: they gave up and dispersed in mid-896.[86]

Alfred is remembered as a literate king. He or his court commissioned the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which was written in Old English (rather than in Latin, the language of the European annals).[87] Alfred's own literary output was mainly of translations, but he also wrote introductions and amended manuscripts.[88]Asser, Alfred the Great, III pp. 121–60. Examples of King Alfred's writings

English unification (10th century)

From 874 to 879 the western half of Mercia was ruled by Ceowulf II, who was succeeded by Æthelred as Lord of the Mercians.[89] Alfred the Great of Wessex styled himself King of the Anglo-Saxons from about 886. In 886/887 Æthelred married Alfred's daughter Æthelflæd.[90] On Alfred's death in 899, his son Edward the Elder succeeded him.[91]

When Æthelred died in 911, Æthelflæd succeeded him as "Lady of the Mercians",[92] and in the 910s she and her brother Edward recovered East Anglia and eastern Mercia from Viking rule.[93] Edward and his successors expanded Alfred's network of fortified burhs, a key element of their strategy, enabling them to go on the offensive.[94][95] When Edward died in 924 he ruled all England south of the Humber. His son, Æthelstan, annexed Northumbria in 927 and thus became the first king of all England. At the Battle of Brunanburh in 937, he defeated an alliance of the Scots, Danes, and Vikings and Strathclyde Britons.[96]

Along with the Britons and the settled Danes, some of the other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms disliked being ruled by Wessex. Consequently, the death of a Wessex king would be followed by rebellion, particularly in Northumbria.[97]Alfred's great-grandson, Edgar, who had come to the throne in 959, was crowned at Bath in 973 and soon afterwards the other British kings met him at Chester and acknowledged his authority.[98]

The presence of Danish and Norse settlers in the Danelaw had a lasting impact; the people there saw themselves as "armies" a hundred years after settlement:[99] King Edgar issued a law code in 962 that was to include the people of Northumbria, so he addressed it to Earl Olac "and all the army that live in that earldom".[100] There are over 3,000 words in modern English that have Scandinavian roots,[101][102] and more than 1,500 place-names in England are Scandinavian in origin; for example, topographic names such as Howe, Norfolk and Howe, North Yorkshire are derived from the Old Norse word haugr meaning hill, knoll, or mound.[103][104] In archaeology and other academic contexts the term Anglo-Scandinavian is often used for Scandinavian culture in England.

Jat History

Dalip Singh Ahlawat[105] writes that Jat Blood flows in the people of England as the Celts, Jutes, Angles, Saxons and Danes were descendants of Scythian Jats. This is evident from Jat Clans surnames still prevalent in England though they follow Christianity. [106]

Arrian[107] mentions that Alexander subjugated Sacians. It is supposed that the Saxones, i.e. Sacasuna, sons of the Sacae, originated from this nation.

Thakur Deshraj[108] writes that warrior Jat groups known by various names like Jeta, Jeti, Goth etc., moved from Iran (Caspian Sea) to Europe, where they were called Shakas and Scythians because Iran was known as Shakadvipa. The inhabitants of Iran were called Shakas . European historians write that the independent states of Germany, known by the name Saxons, were of Shakas (Jats).

ऐंग्लो-सैक्सन

ऐंग्लो-सैक्सन मध्यकालीन यूरोप के जर्मन भाषाएँ बोलने वालीं जातियाँ थीं जिन्होनें दक्षिणी और पूर्वी ब्रिटेन में 5वी शताब्दी ईसवी में घुसकर बसना शुरू कर दिया। ऐंग्लो-सैक्सन में जूट्स, सेक्सन्स और एंगल्स लोग शामिल थे जो जर्मनी की एल्ब नदी के मुहाने और डेन्मार्क के तट पर रहते थे। ये लोग बड़े बहादुर थे। उन्ही की संतति से आधुनिक इंग्लैण्ड राष्ट्र का जन्म हुआ है। इंग्लैण्ड पर उनका राज पांचवी सदी से विलियम विजयी के साथ सन् 1066 में शुरू होने वाले नॉर्मन राज तक जारी रहा। वह "पुरानी अंग्रेज़ी" नाम की एक जर्मन भाषा बोला करते थे।[109]

आठवी सदी में बीड (Bede) नामक इसाई भिक्षु ने लिखा कि ऐंग्लो-सैक्सन लोग तीन क़बीलों की संतान थे:[110]

- ऐंगल लोग (Angles), जो जर्मनी के ऐन्गॅल्न (Angeln) क्षेत्र से आये थे और जिनके नाम पर आगे चलकर "इंग्लैण्ड" का नाम पड़ा। कहा जाता है कि इनका पूरा राष्ट्र ब्रिटेन आ गया और उन्होने अपने पुराने क्षेत्र को किसी कारणवश ख़ाली छोड़ दिया।

इंग्लैण्ड के क्षेत्र में जो लोग पहले से मौजूद थे वे कॅल्ट (Celt) जाति के थे और उन्हें इतिहास में ब्रिटन (Briton) कहा जाता है। उनकी जातियाँ आधुनिक स्कॉटलैंड और वेल्स की जातियों से मिलती-जुलती थीं। ब्रिटनों और ऐंग्लो-सैक्सनों की बहुत सी झडपें हुई और धीरे-धीरे ऐंग्लो-सैक्सनों के ब्रिटनों को इंग्लैण्ड से बाहर धकेल दिया।

जाटों का यूरोप की ओर बढ़ना

ठाकुर देशराज[111] ने लिखा है .... हूणों के आक्रमण के समय जगजार्टिस और आक्सस नदियों के किनारे तथा कैस्पियन सागर के तट पर बसे हुए जाट यूरोप की ओर बढ़ गए। एशियाई देशों में जिस समय हूणों का उपद्रव था, उसी समय यूरोप में जाट लोगों का

[पृ.154]: धावा होता है। कारण कि आंधी की भांति उठे हुए हूणों ने जाटों को उनके स्थानों से उखाड़ दिया था। जाट समूहों ने सबसे पहले स्केंडिनेविया और जर्मनी पर कब्जा किया। कर्नल टॉड, मिस्टर पिंकर्टन, मिस्टर जन्स्टर्न, डिगाइन, प्लीनी आदि अनेक यूरोपियन लेखकों ने उनका जर्मनी, स्केंडिनेविया, रूम, स्पेन, गाल, जटलैंड और इटली आदि पर आक्रमण करने का वर्णन किया है। इन वर्णनों में में कहीं उन्हें, जेटा, कहीं जेटी, और कहीं गाथ नाम से पुकारा है। क्योंकि विजेता जाटों के यह सारे समूह ईरान और का कैस्पियन समुद्र के किनारे से यूरोप की ओर बढ़े थे। इसीलिए यूरोपीय देशों में उन्हें शक व सिथियन के नाम से भी याद किया गया है। ईरान को शाकद्वीप कहते हैं। इसीलिए इरान के निवासी शक कहलाते थे। यूरोपियन इतिहासकारों का कहना है कि जर्मनी की जो स्वतंत्र रियासतें हैं, और जो सैक्सन रियासतों के नाम से पुकारी जाती हैं। इन्हीं शक जाटों की हैं। वे रियासतें विजेता जाटों ने कायम की थी। हम यह मानते हैं और यह भी मानते हैं कि वे जाट शाकद्वीप से ही गए थे। किंतु यूरोपियन लेखकों के दिमाग में इतना और बिठाना चाहते हैं कि शाल-द्वीप में वे जाट भारत से गए थे। और वे उन खानदानों में से थे जो राम, कृष्ण और यदु कुरुओं के कहलाते हैं।

यूरोप में जाने वाले जाटों ने राज्य तो कायम किए ही थे साथ ही उन्होंने यूरोप को कुछ सिखाया भी था। प्रातः बिस्तरे

[पृ.155]: से उठकर नहाना, ईश्वर आराधना करना, तलवार और घोड़े की पूजा, शांति के समय खेती करना,भैंसों से काम लेना यह सब बातें उन्होंने यूरोप को सिखाई थी। कई स्थानों पर उन्होंने विजय स्तंभ भी खड़े किए थे। जर्मनी में राइन नदी के किनारे का उनका स्तंभ काफी मशहूर रहा था।

भारत माता के इन विजयी पुत्रों ने यूरोप में जाकर भी बहुत काल तक वैदिक धर्म का पालन किया था। किंतु परिस्थितियों ने आखिर उन्हें ईसाई होने पर बाध्य कर ही दिया। यदि भारत के धर्म प्रचारक वहां पहुंचते रहते तो वह हरगिज ईसाई ना होते। किंतु भारत में तो सवा दो हजार वर्ष से एक संकुचित धर्म का रवैया रहा है जो कमबख्त हिंदूधर्म के नाम से मशहूर है। उनकी रस्म रिवाजों और समारोहों के संबंध में जो मैटर प्राप्त होता है उसका सारांश इस प्रकार है:-

- जेहून और जगजार्टिस नदी के किनारे के जाट प्रत्येक संक्रांति पर बड़ा समारोह किया करते थे।

- विजयी अटीला जाट सरदार ने एलन्स के किले में बड़े समारोह के साथ खङ्ग पूजा का उत्सव मनाया था।

- जर्मनी के जाट लंबे और ढीले कपड़े पहनते थे और सिर के बालों की एक बेणी बनाकर गुच्छे के समान मस्तक के ऊपर बांध लेते थे।

- स्केंडिनेविया की शिवि और शैवी जाट हरगौरी और धरतीमाता की पूजा किया करते थे। उत्सव पर वे हरिकुलेश और बुद्ध की प्रशंसा के गीत गाते हैं।

- उनके झंडे पर बलराम के हल का चित्र था। युद्ध में वे शूल (बरछे) और मुग्दर (गदा) को काम में लाते थे।

- वे विपत्ति के समय अपनी स्त्रियॉं की सम्मति को बहुत महत्व देते थे।

- उनकी स्त्रियां प्रायः सती होने को अच्छा समझती थी।

- वे विजिट लोगों को गुलाम नहीं मानते थे। उनकी अच्छी बातों को स्वीकार करने में वे अपनी हेटी नहीं समझते थे।

- लड़ाई के समय वे ऐसा ख्याल करते थे कि खून के खप्पर लेकर योगनियां रणक्षेत्र में आती हैं।

बहादुर जाटों के ये वर्णन जहां प्रसन्नता से हमारी छाती को फूलाते हैं वहां हमें हृदय भर कर रोने को भी बाध्य करते हैं। शोक है उन जगत-विजेता वीरों की कीर्ति से भी जाट जगत परिचित नहीं है।

ब्रिटेन पर जूट्स, सेक्सन्स एंगल्स की विजय (410 ई० से 825 ई०)

दलीप सिंह अहलावत[112] लिखते हैं: जूट्स, सेक्सन्स और एंगल्स लोग जर्मनी की एल्ब नदी के मुहाने और डेन्मार्क के तट पर रहते थे। ये लोग बड़े बहादुर थे। ये क्रिश्चियन धर्म के विरोधी थे।

ब्रिटेन से रोमनों के चले जाने के बाद ब्रिटेन के लोग बहुत कमजोर और असहाय थे। इन लोगों पर स्काटलैंड के केल्टिक कबीलों, पिक्ट्स और स्काट्स ने हमला कर दिया। ब्रिटेन निवासियों की इसमें भारी हानि हुई। इनमें इतनी शक्ति न थी कि वे इन हमलों करने वालों को रोक सकें। इसलिए मदद के लिए इन्होंने जूट लोगों को बुलाया। जूट्स ने उसी समय ब्रिटिश सरदार वरटिगर्न (Vortigern) के निमन्त्रण को स्वीकार कर लिया। जटलैण्ड (Jutland) से जाटों की एक विशाल सेना अपने जाट नेता हेंगिस्ट और होरसा (Hengest and Horsa) के नेतृत्व में सन् 449 ई० में केण्ट (Kent) में उतर गई। इन्होंने पिक्ट्स (Picts) और स्कॉट्स (Scots) को हराया और वहां से बाहर निकाल दिया। उन्हें भगाने के बाद जाट ब्रिटेन के लोगों के विरुद्ध हो गये और उन्हें पूरी तरह से अपने वश में कर लिया और 472 ई० तक पूरे केण्ट पर अधिकार कर लिया। यहां पर आबाद हो गये। इसके अतिरिक्त जाटों ने अपना निवास व्हिट द्वीप (Isle of Wight) में किया1।

जटलैण्ड के जाटों की विजय सुनकर उनके दक्षिणवासी सेक्सन्स तथा एंगल्स भी ललचाये। सर्वप्रथम सेक्सन्स ब्रिटेन में पहुंचे और उन्होंने ऐस्सेक्स, मिडिलसेक्स और वेस्सेक्स नाम से तीन राज्य स्थापित किये। वहां पर इन्होंने कुछ बस्तियां आबाद कर दीं। ब्रिटेन की जनता ने बड़ी वीरता से सेक्सन्स का मुकाबला किया और 520 ई० में मोण्डबेडन ने उन्हें करारी हार दी। इस तरह से

- 1. आधार लेख - इंगलैण्ड का इतिहास पृ० 16-17, लेखक प्रो० विशनदास; हिस्ट्री ऑफ ब्रिटेन पृ० 21-22, लेखक रामकुमार लूथरा, अनटिक्विटी ऑफ जाट रेस, पृ० 63-66, लेखक: उजागरसिंह माहिल; जाट्स दी ऐन्शन्ट रूलर्ज पृ० 86 लेखक बी० एस० दहिया तथा जाट इतिहास अंग्रेजी पृ० 43, लेखक ले० रामसरूप जून।

जाट वीरों का इतिहास: दलीप सिंह अहलावत, पृष्ठान्त-399

सेक्सन्स का बढ़ना कुछ समय के लिए रुक गया। परन्तु 577 ई० में डियोरहम की लड़ाई में सेक्सन्स ने केब्लिन के नेतृत्व में ब्रिटेन लोगों पर पूरी विजय प्राप्त कर ली तथा उनको अपना दास बनाए रखा। यह कामयाबी जूट्स (जाटों) की सहायता से हुई थी जिसके लिए सेक्सन्स ने उनसे मांग की थी1।

अब प्रश्न पैदा होता है कि उन जूट्स (जाटों) का क्या हुआ जिन्होंने हेंगिस्ट और होरसा के नेतृत्व में ब्रिटेन के एक बड़े क्षेत्र पर अधिकार कर लिया था और सेक्सन्स को सहायता देकर उनका ब्रिटेन पर अधिकार करवाया। इसका उत्तर यही हो सकता है कि ब्रिटिश इतिहासकारों ने इनके इतिहास को लिखने में पक्षपात किया है।

सेक्सन्स के बाद एंग्ल्स पहुंचे जो जूट्स और सेक्सन्स की तरह ही लड़ाके तथा लुटेरे थे। सन् 613 ई० में नार्थम्ब्रिया के एंग्ल राजा ने ब्रिटेन पर आक्रमण करके विजय प्राप्त की। इसके बाद इन्हीं एगल्स के नाम पर ब्रिटेन का नाम इंग्लैंड हो गया। ये एंगल्स लोग भी जाट थे जैसा कि पिछले पृष्ठों पर लिखा गया है। इंग्लैंड में रहने वालों को अंग्रेज कहा गया।

एंगल्स लोग संख्या में दूसरों से अधिक थे इसी कारण से ब्रिटेन को एंगल्स की भूमि एवं इंग्लैंड कहा गया। इस तरह से ब्रिटेन पर जूट्स, सेक्सन्स और एंगल्स का अधिकार हो गया। इसी को ब्रिटेन पर अंग्रेजों की जीत कहा जाता है। इन तीनों कबीलों ने अपने अलग-अलग राज्य स्थापित किए। जूट्स ने केण्ट (Kent); सैक्सन्स ने सस्सेक्स (Sussex), एस्सेक्स (Essex), वेसेक्स (Wessex) और एंगल्स ने ईस्ट एंगलिया (East Anglia), मर्शिया (Mercia) और नार्थम्ब्रिया (Northumbria) के राज्य स्थापित किये। ये सातों राज्य सामूहिक रूप से हेपटार्की (Heptarchy) कहलाते थे। परन्तु ये राज्य स्वतन्त्र नहीं थे। इन सातों में जो शक्तिशाली होता था वह दूसरों का शासक बन जाता था।

ऊपर कहे हुए तीनों कबीले संगठित नहीं थे। नॉरमनों ने जब तक इस देश को नहीं जीता, इंग्लैंड में शक्तिशाली केन्द्रीय राज्य की स्थापना नहीं हो सकी। इन कबीलों ने देश से क्रिश्चियन धर्म और रोमन सभ्यता को मिटा दिया। आधुनिक इंग्लैंड एंग्लो-सैक्सन्स का बनाया हुआ है। आधुनिक अंग्रेज किसी न किसी रूप में इंग्लो-सैक्सन्स के ही वंशज हैं।

अंग्रेज जाति की उत्पत्ति और बनावट के सम्बन्ध में दो प्रतिद्वन्द्वी सिद्धान्त हैं।

- पलग्रोव, पियरसन और सेछम आदि प्रवीण मनुष्य रोमन केल्टिक सिद्धान्त को मानते हैं। उनका यह विचार है कि आधुनिक इंग्लैंड में रोमन-केल्टिक रक्त और संस्थाएं मौजूद हैं।

- ग्रीन और स्टब्स जैसे दूसरे प्रवीन मनुष्य ट्यूटानिक सिद्धान्त को मानते हैं। उनका यह विचार है कि ट्यूटानिक अर्थात् जूट, एंगल, सैक्सन और डेन लोगों का रक्त और संस्थाएं बहुत कुछ आधुनिक इंग्लैंड में पाई जाती हैं। इन दोनों में से ट्यूटानिक सिद्धान्त अधिक माना जाता

- 1. आधार लेख - इंग्लैण्ड का इतिहास पृ० 16-17, लेखक प्रो० विशनदास; ए हिस्ट्री ऑफ ब्रिटेन पृ० 21-22, लेखक रामकुमार लूथरा; अनटिक्विटी ऑफ जाट रेस, पृ० 63-66, लेखक: उजागरसिंह माहिल; जाट्स दी ऐन्शन्ट रूलर्ज पृ० 86 लेखक: बी० एस० दहिया तथा जाट इतिहास अंग्रेजी पृ० 43, लेखक ले० रामसरूप जून।

जाट वीरों का इतिहास: दलीप सिंह अहलावत, पृष्ठान्त-400

- है और आमतौर पर यह स्वीकार किया जाता है कि ब्रिटिश जाति मिले-जुले लोगों की जाति है। जिनमें ट्यूटानिक तत्त्व प्रधान है, जबकि केल्टिक तत्त्व भी पश्चिम में और आयरलैंड में बहुत कुछ बचा हुआ है1।

इसका सार यह है कि इंगलैंड द्वीपसमूह के मनुष्यों की रगों में आज भी अधिकतर जाट रक्त बह रहा है। क्योंकि केल्टिक आर्य लोग तथा जूट, एंगल, सैक्सन और डेन लोग जाटवंशज थे। आज भी वहां पर अनेक जाटगोत्रों के मनुष्य विद्यमान हैं जो कि धर्म से ईसाई हैं।

See also

References

- ↑ Higham, Nicholas J., and Martin J. Ryan. The Anglo-Saxon World. Yale University Press, 2013. pp. 7–19

- ↑ Campbell. The Anglo-Saxon State. p. 10

- ↑ Hills, C. (2003) Origins of the English Duckworth, London. ISBN 0-7156-3191-8, p. 67

- ↑ "Buckingham". Unlocking Buckinghamshire's Past. Buckinghamshire County Council.

- ↑ Gelling, Margaret (1956), "Some notes on the place-names of Birmingham and the surrounding district", Transactions & Proceedings, Birmingham Archaeological Society (72): 14–17, ISSN 0140-4202 p.14

- ↑ Gelling 1992, p. 140

- ↑ Higham, Nicholas J., and Martin J. Ryan. The Anglo-Saxon World. Yale University Press, 2013. pp. 7–19

- ↑ Jones. The end of Roman Britain: Military Security. pp. 164–68. The author discusses the failings of the Roman army in Britain and the reasons why they eventually left.

- ↑ Morris. The Age of Arthur. pp. 56–62. Picts and Saxons.

- ↑ Morris. The Age of Arthur. pp. 56–62. Picts and Saxons.

- ↑ Morris. Age of Arthur. p. 75. – Gildas: "... The federate complained that their monthly deliveries were inadequately paid..." – "All the greater towns fell to their enemy...."

- ↑ Dark. Britain and the End of the Roman Empire. p. 29. Referring to Gildas text about a letter: "The Britons...still felt it possible to appeal to Aetius, a Roman military official in Gaul in the mid-440s"

- ↑ Morris. The Age of Arthur. Chapter 6. The War

- ↑ Gildas. The Ruin of Britain. II.26 – Mount Badon is referred to as Bath-Hill in this translation of Gildas text.

- ↑ Myers, The English Settlements, Chapter 4: The Romano British Background and the Saxon Shore. Myers identifies incidence of German people in Britain during the Roman occupation.

- ↑ Myers, The English Settlements, Chapter 4: The Romano British Background and the Saxon Shore. Myers identifies incidence of German people in Britain during the Roman occupation.

- ↑ Cassius Dio, Roman History, Book LX, ppp.417,419

- ↑ Forster et al. MtDNA Markers for Celtic and Germanic Language Areas in the British Isles in Jones. Traces of ancestry: studies in honour of Colin Renfrew. pp. 99–111

- ↑ Ward-Perkins. The fall of Rome: and the end of civilisation Particularly pp. 38–39

- ↑ Welch, Anglo-Saxon England, Chapter 8: From Roman Britain to Anglo-Saxon England

- ↑ Myers. The English Settlements, Chapter 5: Saxons, Angles and Jutes on the Saxon Shore

- ↑ Jones. The End of Roman Britain. p. 71. – ..the repetitious entries for invading ships in the Chronicle (three ships of Hengest and Horsa; three ships of Aella; five ships of Cerdic and Cynric; two ships of Port; three ships of Stuf and Wihtgar), drawn from preliterate traditions including bogus eponyms and duplications, might be considered a poetic convention.

- ↑ Morris, The Age of Arthur, Ch.14:Brittanny

- ↑ Bell-Fialkoff/ Bell: The role of migration in the history of the Eurasian steppe, p. 303. That is why many scholars still subscribe to the traditional view that combined archaeological, documentary and linguistic evidence suggests that considerable numbers of Anglo-Saxons settled in southern and eastern England.

- ↑ Hunter-Blair, Roman Britain and early England Particularly Chapter 8: The Age of Invasion

- ↑ Bede. Ecclesiastical History of the English People I.15.

- ↑ Welch, Anglo-Saxon England. A complete analysis of Anglo-Saxon Archaeology. A discussion of where the settlers came from, based on a comparison of pottery with those found in the area of origin in Germany. Burial customs and types of building.

- ↑ Heinrich Härke. Ethnicity and Structures in Hines. The Anglo-Saxons pp. 148–49

- ↑ Heinrich Härke. Ethnicity and Structures in Hines. The Anglo-Saxons pp. 148–49

- ↑ Jones, The End of Roman Britain, Ch. 1: Population and the Invasions; particularly pp. 11–12: "In contrast, some scholars shrink the numbers of the Anglo-Saxon invaders to a small, potent elite of only a few thousand invaders."

- ↑ Stefan Burmeister, Archaeology and Migration (2000): " ... immigration in the nucleus of the Anglo-Saxon settlement does not seem aptly described in terms of the "elite-dominance model.To all appearances, the settlement was carried out by small, agriculture-oriented kinship groups. This process corresponds more closely to a classic settler model. The absence of early evidence of a socially demarcated elite underscores the supposition that such an elite did not play a substantial role. Rich burials such as are well known from Denmark have no counterparts in England until the 6th century. At best, the elite-dominance model might apply in the peripheral areas of the settlement territory, where an immigration predominantly comprised of men and the existence of hybrid cultural forms might support it."

- ↑ Gildas. The Ruin of Britain. II.25 -With their unnumbered vows they burden heaven, that they might not be brought to utter destruction, took arms under the conduct of Ambrosius Aurelianus, a modest man, who of all the Roman nation was then alone in the confusion of this troubled period by chance left alive.

- ↑ Gildas. The Ruin of Britain. II.26 – Mount Badon is referred to as Bath-Hill in this translation of Gildas text.

- ↑ Gildas. The Ruin of Britain. II.26 – Mount Badon is referred to as Bath-Hill in this translation of Gildas text.

- ↑ Gildas. The Ruin of Britain. II.26 – Mount Badon is referred to as Bath-Hill in this translation of Gildas text.

- ↑ Morris, The Age of Arthur, Chapter 16: English Conquest

- ↑ Morris, The Age of Arthur, Chapter 16: English Conquest

- ↑ Gildas.The Ruin of Britain I.1.

- ↑ Morris, The Age of Arthur, Chapter 16: English Conquest

- ↑ Snyder.The Britons. p. 85

- ↑ tenton. Anglo-Saxon England. p. 29.

- ↑ Stenton. Anglo-Saxon England. p. 30.

- ↑ Morris. The Age of Arthur. p. 299

- ↑ Wood.The Domesday Quest. pp. 47–48

- ↑ Greenway, Historia Anglorum, pp. lx–lxi. "The HA (Historia Anglorum) is the story of the unification of the English monarchy. To project such an interpretation required Henry (of Huntingdon) to exercise firm control over his material. One of the products of this control was his creation of the Heptarchy, which survived as a concept in historical writing into our own time".

- ↑ Norman F. Cantor, The Civilization of the Middle Ages1993:163f.

- ↑ Bede Ecclesiastical History of the English People, Tr. Shirley-Price, I.25

- ↑ Charles-Edwards After-Rome: Nations and Kingdoms, pp. 38–39

- ↑ Charles-Edwards After-Rome: Nations and Kingdoms, pp. 38–39

- ↑ Charles-Edwards After-Rome: Nations and Kingdoms, pp. 38–39

- ↑ Snyder,The Britons, p. 176.

- ↑ Bede, History of the English, II.20

- ↑ Snyder, The Britons, p. 177

- ↑ Snyder.The Britons. p. 178

- ↑ Snyder.The Britons. p. 178

- ↑ Snyder.The Britons. p. 212

- ↑ Snyder.The Britons. p. 212

- ↑ Snyder.The Britons. p. 178

- ↑ Snyder.The Britons.pp. 178–79

- ↑ Snyder.The Britons.pp. 178–79

- ↑ Stenton. Anglo-Saxon England. p. 231

- ↑ Sawyer, The Oxford illustrated history of Vikings, p. 1.

- ↑ Sawyer, The Oxford illustrated history of Vikings, pp. 2–3.

- ↑ Standard English words which have a Scandinavian Etymology. Viking: "Northern pirate. Literally means creek dweller."

- ↑ Sawyer, The Oxford illustrated history of Vikings, pp. 2–3.

- ↑ Starkey,Monarchy, Chapter 6: Vikings

- ↑ Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, 793.This year came dreadful fore-warnings over the land of the Northumbrians, terrifying the people most woefully: these were immense sheets of light rushing through the air, and whirlwinds, and fiery dragons flying across the firmament. These tremendous tokens were soon followed by a great famine: and not long after, on the sixth day before the ides of January in the same year, the harrowing inroads of heathen men made lamentable havoc in the church of God in Holy-island (Lindisfarne), by rapine and slaughter.

- ↑ Starkey, Monarchy, p. 51

- ↑ Starkey, Monarchy, p. 51

- ↑ Starkey, Monarchy, p. 51

- ↑ Starkey, Monarchy, p. 51

- ↑ Asser, Alfred the Great, pp. 84–85.

- ↑ Asser, Alfred the Great, pp. 84–85.

- ↑ Asser, Alfred the Great, pp. 84–85.

- ↑ Asser, Alfred the Great, p. 22.

- ↑ Medieval Sourcebook: Alfred and Guthrum's Peace

- ↑ Wood, The Domesday Quest, Chapter 9: Domesday Roots. The Viking Impact

- ↑ Starkey, Monarchy, p. 63

- ↑ Starkey, Monarchy, p. 63

- ↑ Horspool, Alfred, p. 102. A hide was somewhat like a tax – it was the number of men required to maintain and defend an area for the King. The Burghal Hideage defined the measurement as one hide being equivalent to one man. The hidage explains that for the maintenance and defence of an acre's breadth of wall, sixteen hides are required.

- ↑ Anglo-Saxon Chronicle 894.

- ↑ Starkey, Monarchy, pp. 68–69.

- ↑ Starkey, Monarchy, p. 64

- ↑ Anglo-Saxon Chronicle 891

- ↑ Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, 891–896

- ↑ Horspool, "Why Alfred Burnt the Cakes", The Last War, pp. 104–10.

- ↑ Horspool, "Why Alfred Burnt the Cakes", pp. 10–12

- ↑ Horspool, "Why Alfred Burnt the Cakes", pp. 10–12

- ↑ Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England, p. 123

- ↑ Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England, p. 123

- ↑ Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, 899

- ↑ Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England, p. 123

- ↑ Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England, p. 123

- ↑ Starkey, Monarchy, p. 71

- ↑ Welch, Late Anglo-Saxon England pp. 128–29

- ↑ Starkey, Monarchy, p. 71

- ↑ Starkey, Monarchy, p. 71

- ↑ Keynes, 'Edgar', pp. 48–51

- ↑ Woods, The Domesday Quest, pp. 107–08

- ↑ Woods, The Domesday Quest, pp. 107–08

- ↑ The Viking Network: Standard English words which have a Scandinavian Etymology.

- ↑ Crystal, The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language pp. 25–26.

- ↑ Crystal, The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language pp. 25–26.

- ↑ Ordnance Survey: Guide to Scandinavian origins of place names in Britain

- ↑ Jat History Dalip Singh Ahlawat/Chapter IV, p.401

- ↑ Ujagar Singh Mahil: Antiquity of Jat Race, p.66-70

- ↑ Arrian:The Anabasis of Alexander/7a, Ch.10

- ↑ Thakur Deshraj: Jat Itihas (Utpatti Aur Gaurav Khand)/Navam Parichhed,p.153-156

- ↑ Richard M. Hogg, ed. The Cambridge History of the English Language: Vol 1: the Beginnings to 1066 (1992)

- ↑ "English and Welsh are races apart".

- ↑ Thakur Deshraj: Jat Itihas (Utpatti Aur Gaurav Khand)/Navam Parichhed,p.153-156

- ↑ Jat History Dalip Singh Ahlawat/Chapter IV, pp.399-401