Birmingham

| Author:Laxman Burdak, IFS (R) |

Birmingham (बर्मिंघम) is a city and metropolitan borough in the West Midlands region of England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom, with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper.

Location

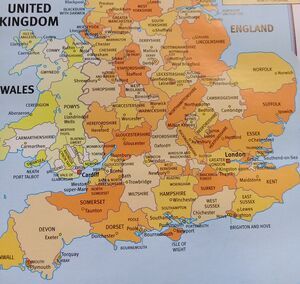

Located in the West Midlands region of England, approximately 160 km from London, Birmingham is considered to be the social, cultural, financial and commercial centre of the Midlands. Distinctively, Birmingham only has small rivers flowing through it, mainly the River Tame and its tributaries River Rea and River Cole – one of the closest main rivers is the Severn, approximately 32 km west of the city centre.

Etymology

The name Birmingham comes from the Old English Beormingahām,[1] meaning the home or settlement of the Beormingas – a tribe or clan whose name literally means 'Beorma's people' and which may have formed an early unit of Anglo-Saxon administration.[2] Beorma, after whom the tribe was named, could have been its leader at the time of the Anglo-Saxon settlement, a shared ancestor, or a mythical tribal figurehead.

Place names ending in -ingahām are characteristic of primary settlements established during the early phases of Anglo-Saxon colonisation of an area, suggesting that Birmingham was probably in existence by the early 7th century at the latest.[3]Surrounding settlements with names ending in -tūn ('farm'), -lēah ('woodland clearing'), -worð ('enclosure') and -field ('open ground') are likely to be secondary settlements created by the later expansion of the Anglo-Saxon population,[4] in some cases possibly on earlier British sites.[5]

Jat clans

Pre-history and medieval History

There is evidence of early human activity in the Birmingham area dating back to around 8000 BC,[7] with Stone Age artefacts suggesting seasonal settlements, overnight hunting parties and woodland activities such as tree felling.[8] The many burnt mounds that can still be seen around the city indicate that modern humans first intensively settled and cultivated the area during the Bronze Age, when a substantial but short-lived influx of population occurred between 1700 BC and 1000 BC, possibly caused by conflict or immigration in the surrounding area.[9] During the 1st-century Roman conquest of Britain, the forested country of the Birmingham Plateau formed a barrier to the advancing Roman legions,[10] who built the large Metchley Fort in the area of modern-day Edgbaston in AD 48,[11] and made it the focus of a network of Roman roads.[12]

The development of Birmingham into a significant urban and commercial centre began in 1166, when the Lord of the Manor Peter de Bermingham obtained a charter to hold a market at his castle, and followed this with the creation of a planned market town and seigneurial borough within his demesne or manorial estate, around the site that became the Bull Ring.[13] This established Birmingham as the primary commercial centre for the Birmingham Plateau at a time when the area's economy was expanding rapidly, with population growth nationally leading to the clearance, cultivation and settlement of previously marginal land.[14] Within a century of the charter Birmingham had grown into a prosperous urban centre of merchants and craftsmen.[15] By 1327 it was the third-largest town in Warwickshire,[16] a position it would retain for the next 200 years.

History

Historically a market town in Warwickshire in the medieval period, Birmingham grew during the 18th century during the Midlands Enlightenment and during the Industrial Revolution, which saw advances in science, technology and economic development, producing a series of innovations that laid many of the foundations of modern industrial society.[17][18] By 1791, it was being hailed as "the first manufacturing town in the world".[19]Birmingham's distinctive economic profile, with thousands of small workshops practising a wide variety of specialised and highly skilled trades, encouraged exceptional levels of creativity and innovation; this provided an economic base for prosperity that was to last into the final quarter of the 20th century. The Watt steam engine was invented in Birmingham.[20]

The resulting high level of social mobility also fostered a culture of political radicalism which, under leaders from Thomas Attwood to Joseph Chamberlain, was to give it a political influence unparalleled in Britain outside London and a pivotal role in the development of British democracy.[21]

From the summer of 1940 to the spring of 1943, Birmingham was bombed heavily by the German Luftwaffe in what is known as the Birmingham Blitz. The damage done to the city's infrastructure, in addition to a deliberate policy of demolition and new building by planners, led to extensive urban regeneration in subsequent decades.

Jat History

Bharatpur (भरतपुर) is a village Aston in England. Aston is a ward of Central Birmingham, England. Located immediately to the north-east of Central Birmingham, Aston constitutes a ward within the metropolitan authority.

Origin: The fort of Bharatpur is the only fort in India which was never physically captured by the British. The British were impressed by the bravery of Jats of Bharatpur. So they named this village after Bharatpur.

Ram Sarup Joon[22] writes that ... On 7th Jan. 1805 Lord Lake explored every possible avenue to penetrate the fort. A large number of British Officers and soldiers were killed in this action, the supply of rations and ammunition ran short and they failed in capturing the fort. They employed 5 inch and 7 inch guns but these did not make much impression on the thick mud walls. After two days, they succeeded in creating a break in the Southern Wall and the fort was charged by four Indian units and 1,500 British troops. The Jats repulsed this attack after inflicting heavy casualties. Colonel Maitland and 400 troops were killed. The British advanced for the third time and attacked the fort under the covering fire of heavy Artillery. The troops bravely crossed the mote and tried to scale the walls of the fort. As they came up the Jats kept killing them till the mote was filled with dead bodies, General Smith and Col Meeker, commanders of the British troops requested Lord Lake to sign a peace treaty with Jats.

Jats in Birmingham Commonwealth Games 2022

The 2022 Commonwealth Games, officially known as the XXII Commonwealth Games were held at Birmingham, England, from 28 July to 8 August 2022. The performance of India's Jats at the 2022 Commonwealth Games was so outstanding that Rajdeep Sardesai, writing in the Hindustan Times, referred to such stellar performance as the : " 'Jatification' of Indian sport" : out of the 56 medals won by India just over a quarter, 25, went to Jats who also won 10 of the 19 gold medals (so over half of the gold medals awarded).

The Times is a British daily national newspaper based in London. The Times Sports wrote on 7 August 2022 - Jats have hoisted India's tricolour abroad by winning 18 medals in commonwealth...It calls Jats the most powerful race.

विदेशी अखबार में देशी जाट। 2022 बर्मिंघम) कामनवेल्थ खेलों में ज़ाट खिलाड़ियों क़े अभूतपूर्व प्रदर्शन क़ो लेकर इंग्लैंड क़े प्रसिद्ध समाचार पत्र The Times ने जाटों क़ी उपलब्धियों क़ी खुलक़र प्रशंसा क़ी है। साथ ही समाचार पत्र ने जाटों क़ो दुनिया क़ी सबसे ताक़तवर Race लिखकर अत्यधिक सम्मान दिया है!

Here is the list of Jats who won medals (to be completed):

- Annu Rani (Dhankhar) scripted history as she became the first Indian female javelin thrower to win a bronze medal in the Commonwealth Games in Birmingham. She is from Bahadurpur, Meerut, Uttar Pradesh.

- Amit Panghal won Gold medal in Commonwealth Games 2022 at Birmingham in 51kg flyweight category on 7 August 2022. Amit Panghal beat England’s Kiaran McDonald by unanimous decision in the final to win his first CWG gold. He is from Mayna village of Rohtak district, Haryana.

- Anshu Malik bags silver medal for India in Women’s Freestyle 57 kg wrestling in Birmingham Commonwealth Games 2022. She is from Nidani, Jind district, Haryana.

- Bajrang Punia won the gold medal in the men’s 65kg freestyle wrestling category at Birmingham Commonwealth Games 2022. He is from village Khudan, tehsil & district Jhajjar, Haryana.

- Deepak Nehra won a bronze medal in the 2022 Birmingham Commonwealth Games, defeated Pakistan's Tayab Raza 10-2 to win the 97kg freestyle wrestling. He is from village Nindana, Maham, Rohtak, Haryana.

- Deepak Punia beats Pakistan’s Muhammad Inam to win gold. He won the gold medal in the men’s 86kg freestyle wrestling category at Birmingham 2022.

- Divya Kakran clinched a bronze medal in the women's freestyle 58kg wrestling in Birmingham Commonwealth Games 2022.

- Gurdeep Singh won bronze medal at the 2022 Commonwealth Games in the 109+ kg category.[

- Harjinder Kaur won bronze medal at the 2022 Commonwealth Games.

- Jaismine Lamboria won Bronze Medal in 2022 Commonwealth Games and Lightweight (60 kg).

- Lovepreet Singh won bronze medal at the 2022 Commonwealth Games in the men's 109 kg weight category.

- Mohit Grewal won a bronze medal in the 2022 Birmingham Commonwealth Games.

- Naveen Malik secured gold after beating Pakistan's Muhammad Sharif Tahir via technical superiority in men's 74kg final.

- Nitu Ghanghas won the gold medal on her Commonwealth Games debut at Birmingham in the 45kg-48kg (minimum weight) category by beating the home favourite Demie-Jade with a score of 0-5 in her favour.

- Pooja Gehlot won the bronze medal in the women's 50 kg event at the 2022 Commonwealth Games held in Birminghamdefeated defeating Scotland's Christelle Lemofack Letchidjio in women's 50kg freestyle.

- Pooja Sihag won bronze medal in the women's 76 kg event at the 2022 Commonwealth Games held in Birmingham against Australia's Naomi de Bruine.

- Ravi Dahiya won gold medal in wrestling at the Commonwealth Games 2022 in Birmingham. He produced a commanding display against Nigeria's Ebikewenimo Welson and secured a 10-0 win in the men's 57kg final.

- Rohit Tokas settled for bronze in boxing after losing semifinal match. Rohit lost 2-3 in the 67kg category.

- Sagar Ahlawat - He participated in the 2022 Commonwealth Games, being awarded the silver medal in the boxing competition in the superheavy weight (92kg) division in Birmingham. The score was 5-0.

- Sakshi Malik defeated Ana Godinez Gonzales of Canada to win gold in the women's 62kg freestyle wrestling final at the Commonwealth Games 2022.

- Sudhir Lath - Sudhir won India’s sixth gold medal at the 2022 Commonwealth Games in Birmingham with a fine performance in the Para Powerlifting men’s heavyweight

- Tulika Maan won silver medal in the 78 kg weight class in Commonwealth Games 2022.

- Vinesh Phogat defeated Sri Lanka wrestler for a gold in women's 53kg freestyle event.

-

The Times News Paper on Jats the most poerful race

-

Sakshi Malik in Commonwealth Games-2022

-

Commonwealth Me India Ke Jaton Ka Danka

Economy

Birmingham's economy is now dominated by the service sector. The city is a major international commercial centre and an important transport, retail, events and conference hub. Its metropolitan economy is the second-largest in the United Kingdom with a GDP of $121.1bn (2014).[23] Its five universities,[24] including the University of Birmingham, make it the largest centre of higher education in the country outside London.[25]

Birmingham's major cultural institutions – the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, the Birmingham Royal Ballet, the Birmingham Repertory Theatre, the Library of Birmingham and the Barber Institute of Fine Arts – enjoy international reputations,[26] and the city has vibrant and influential grassroots art, music, literary and culinary scenes.[27] The city will host the 2022 Commonwealth Games.[28] As of 2014, Birmingham is the fourth most visited city in the UK by people from foreign nations.[29]

External links

References

- ↑ Gelling, Margaret (1956), "Some notes on the place-names of Birmingham and the surrounding district", Transactions & Proceedings, Birmingham Archaeological Society (72): 14–17, ISSN 0140-4202 p.14

- ↑ Gelling 1992, p. 140

- ↑ Gelling 1956, pp. 14–15

- ↑ Thorpe, H. (1950), "The Growth of Settlement before the Norman Conquest", in Kinvig, R. H.; Smith, J. G.; Wise, M. J. (eds.), Birmingham and its Regional Setting: A Scientific Survey, S. R. Publishers Limited (published 1970), pp. 87–97, ISBN 978-0-85409-607-7,p.106

- ↑ Bassett, Steven (2000), "Anglo-Saxon Birmingham" (PDF), Midland History, University of Birmingham, 25 (25): 1–27, doi:10.1179/mdh.2000.25.1.1, ISSN 0047-729X, S2CID 161966142, archived from the original (PDF) on 16 March 2009, p.7

- ↑ Jat History Dalip Singh Ahlawat/Parishisht-I, s.n. 80

- ↑ Hodder, Mike (2004). Birmingham: the hidden history. Stroud: Tempus Publishing. ISBN 0-7524-3135-8.p.23

- ↑ Hodder 2004, pp. 24–25

- ↑ Hodder 2004, pp. 33, 43

- ↑ Thorpe, H. (1970) [1950]. "The Growth of Settlement before the Norman Conquest". In Kinvig, R. H.; Smith, J. G.; Wise, M. G. (eds.). Birmingham and its Regional Setting: A Scientific Survey. New York: S. R. Publishers Limited. pp. 87–97. ISBN 0-85409-607-8.

- ↑ Hodder 2004, p. 51

- ↑ Leather, Peter (1994). "The Birmingham Roman Roads Project". West Midlands Archaeology. 37 (9). Archived from the original

- ↑ Leather, Peter (2001). A brief history of Birmingham. Studley: Brewin Books. ISBN 1-85858-187-7. p. 9; Demidowicz, George (2008). Medieval Birmingham: the borough rentals of 1296 and 1344-5. Dugdale Society Occasional Papers. Stratford-upon-Avon: The Dugdale Society, in association with the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust.

- ↑ Leather 2001, p. 9

- ↑ Holt, Richard (1986). The early history of the town of Birmingham, 1166–1600. Dugdale Society Occasional Papers. Oxford: Printed for the Dugdale Society by D. Stanford, Printer to the University. ISBN 0-85220-062-5.,p.4

- ↑ Leather 2001, p. 12

- ↑ Uglow, Jenny (2011) [2002]. The Lunar Men: The Inventors of the Modern World 1730–1810. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-26667-8. p. pp. iv, 860–861

- ↑ Jones, Peter M. (2008). Industrial Enlightenment: Science, technology and culture in Birmingham and the West Midlands, 1760–1820. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-7770-8. pp. 14, 19, 71, 82–83, 231–232

- ↑ Hopkins, Eric (1989). Birmingham: The First Manufacturing Town in the World, 1760–1840. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-79473-6.p.26

- ↑ Berg, Maxine (1991). "Commerce and Creativity in Eighteenth-Century Birmingham". In Berg, Maxine (ed.). Markets and Manufacture in Early Industrial Europe. London: Routledge. pp. 173–202. ISBN 0-415-03720-4., pp. 174, 184

- ↑ Ward 2005, jacket; Briggs, Asa (1990) [1965]. Victorian Cities. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. pp. 185, 187–189. ISBN 0-14-013582-0.; Jenkins, Roy (2004). Twelve cities: a personal memoir. London: Pan Macmillan. pp. 50–51. ISBN 0-330-49333-7.

- ↑ History of the Jats/Chapter X,p. 172

- ↑ "Global city GDP 2014". Brookings Institution.

- ↑ "Universities in Birmingham - Birmingham City Council". Birmingham City Council.

- ↑ https://www.hesa.ac.uk/dox/dataTables/studentsAndQualifiers/download/institution0809.xls?v=1.0

- ↑ Maddocks, Fiona (6 June 2010). "Andris Nelsons, magician of Birmingham". The Observer. London: Guardian News and Media.

- ↑ Price, Matt (2008). "A Hitchhiker' s Guide to the Gallery – Where to see art in Birmingham and the West Midlands" (PDF). London: Arts Co.

- ↑ "Home of the Birmingham 2022 Commonwealth Games". B2022.

- ↑ "8". Travel trends: 2014 (Report). Office for National Statistics.