Issedones

| Author: Laxman Burdak, IFS (R). |

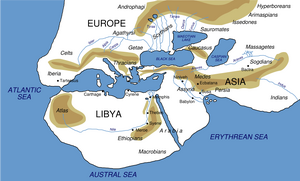

Issedones (Ἰσσηδόνες) were an ancient people of Central Asia at the end of the trade route leading north-east from Scythia, described in the lost Arimaspeia[1] of Aristeas, by Herodotus in his History (IV.16-25) and by Ptolemy in his Geography.

Like the Massagetae to the south, the Issedones are described by Herodotus as similar to, yet distinct from, the Scythians.

Variants

- Issedones (Ἰσσηδόνες)

- Essedones (Pliny.vi.19)

Jat Gotras Namesake

Location

The exact location of their territorial span in Central Asia is unknown. The Issedones are "placed by some in Western Siberia and by others in Chinese Turkestan," according to E. D. Phillips.[2]

Herodotus, who allegedly got his information through both Greek and Scythian sources, describes them as living east of Scythia and north of the Massagetae, while the geographer Ptolemy (VI.16.7) appears to place the trading stations of Issedon Scythica and Issedon Serica in the Tarim Basin.[3] Some speculate that they are the people described in Chinese sources as the Wusun.[4] J.D.P. Bolton places them further north-east, on the south-western slopes of the Altay mountains.[5]

Another location of the land of the Issedones can be inferred from the account of Pausanias. According to what the Greek traveller was told at Delos in the second century CE, the Arimaspi were north of the Issedones, and the Scythians were south of them:

- At Prasiai (in Attika) is a temple of Apollo. Hither they say are sent the first-fruits of the Hyperboreans, and the Hyperboreans are said to hand them over to the Arimaspoi, the Arimaspoi to the Issedones, from these the Skythians bring them to Sinope, thence they are carried by Greeks to Prasiai, and the Athenians take them to Delos." - Pausanias 1.31.2

The two cities of Issedon Scythia and Issedon Serica have been identified with five cities in the Tarim Basin: Qiuci, Yanqi, Shule, Gumo, and Jingjue, while Yutian is identified with the latter.

History

The Issedones were known to Greeks as early as the late seventh century BCE, for Stephanus Byzantinus[6] reports that the poet Alcman mentioned "Essedones" and Herodotus reported that a legendary Greek of the same time, Aristeas son of Kaustrobios of Prokonnessos (or Cyzicus), had managed to penetrate the country of the Issedones and observe their customs first-hand. Ptolemy relates a similar story about a Syrian merchant.

The Byzantine scholiast John Tzetzes, who sites the Issedones generally "in Scythia", quotes some lines to the effect that the Issedones "exult in long flowing hair" and mentions the one-eyed men to the north.

According to Herodotus, the Issedones practiced ritual cannibalism of their elderly males, followed by a ritual feast at which the deceased patriarch's family ate his flesh, gilded his skull, and placed it in a position of honor much like a cult image.[7] In addition, the Issedones were supposed to have kept their wives in common. This may indicate institutionalized polyandry and a high status for women (Herodotus IV.26: "and their women have equal rights with the men").

Mention by Pliny

Pliny[8] mentions Lake Mieotis and the adjoining nations.... There are some writers who state that there are the following nations dwelling around the Mæotis, as far as the Ceraunian mountains;13 at a short distance from the shore, the Napitæ, and beyond them, the Essedones, who join up to the Colchians, and dwell upon the summits of the mountains:

13 The Ceraunian mountains were a range belonging to the Caucasian chain, and situate at its eastern extremity; the relation of this range to the chain has been variously stated by the different writers.

Mention by Pliny

Pliny[9] mentions The nations of Scythia and the countries on the Eastern Ocean..... Beyond this river (Jaxartes) are the peoples of Scythia. The Persians have called them by the general name of Sacæ,1 which properly belongs to only the nearest nation of them. The more ancient writers give them the name of Aramii. The Scythians themselves give the name of "Chorsari" to the Persians, and they call Mount Caucasus Graucasis, which means "white with snow."

The multitude of these Scythian nations is quite innumerable: in their life and habits they much resemble the people of Parthia.

The tribes among them that are better known are the Sacæ, the Massagetæ,2 the Dahæ,3 the Essedones,4 the Ariacæ,5 the Rhymmici, the Pæsici, the Amardi,6 the Histi, the Edones, the Came, the Camacæ, the Euchatæ,7 the Cotieri, the Anthusiani, the Psacæ, the Arimaspi,8 the Antacati, the Chroasai, and the Œtei; among them the Napæi9 are said to have been destroyed by the Palæi.

1 The Sacæ probably formed one of the most numerous and most powerful of the Scythian Nomad tribes, and dwelt to the east and north-east of the Massagetæ, as far as Servia, in the steppes of Central Asia, which are now peopled by the Kirghiz Cossacks, in whose name that of their ancestors, the Sacæ, is traced by some geographers. 2 Meaning the "Great Getæ." They dwelt beyond the Jaxartes and the Sea of Aral, and their country corresponds to that of the Khirghiz Tartars in the north of Independent Tartary.

3 The Dahæ were a numerous and warlike Nomad tribe, who wandered over the vast steppes lying to the east of the Caspian Sea. Strabo has grouped them with the Sacæ and Massagetæ, as the great Scythian tribes of Inner Asia, to the north of Bactriana.

4 See also B. iv. c. 20, and B. vi. c. 7. The position of the Essedones, or perhaps more correctly, the Issedones, may probably be assigned to the east of Ichim, in the steppes of the central border of the Kirghiz, in the immediate vicinity of the Arimaspi, who dwelt on the northern declivity of the Altaï chain. A communication is supposed to have been carried on between these two peoples for the exchange of the gold that was the produce of those mountain districts.

5 They dwelt, according to Ptolemy, along the southern banks of the Jaxartes.

6 Or the Mardi, a warlike Asiatic tribe. Stephanus Byzantinus, following Strabo, places the Amardi near the Hyrcani, and adds, "There are also Persian Mardi, without the a;" and, speaking of the Mardi, he mentions them as an Hyrcanian tribe, of predatory habits, and skilled in archery.

7 D'Anville supposes that the Euchatæ may have dwelt at the modern Koten, in Little Bukharia. It is suggested, however, by Parisot, that they may have possibly occupied a valley of the Himalaya, in the midst of a country known as "Cathai," or the "desert."

8 The first extant notice of them is in Herodotus; but before him there was the poem of Aristeas of Proconnesus, of which the title was 'Arimaspea;' and it is mainly upon the statements in it that the stories told relative to this people rest—such as their being one-eyed, and as to their stealing the gold from the Gryphes, or Griffins, under whose custody it was placed. Their locality is by some supposed to have been on the left bank of the Middle Volga, in the governments of Kasan, Simbirsk, and Saratov: a locality which is sufficiently near the gold districts of the Uralian chain to account for the legends connecting them with the Gryphes, or guardians of the gold.

9 The former reading was, "The Napæi are said to have perished as well as the Apellæi." Sillig has, however, in all probability, restored the correct one. "Finding," he says, "in the work of Diodorus Siculus, that two peoples of Scythia were called, from their two kings, who were brothers, the Napi and the Pali, we have followed close upon the footsteps of certain MSS. of Pliny, and have come to the conclusion that some disputes aro

References

- ↑ The few fragmentary quoted lines are assembled by Kinkel, Epicorum graecorum fragments, 243-47.

- ↑ Phillips, "The Legend of Aristeas: Fact and Fancy in Early Greek Notions of East Russia, Siberia, and Inner Asia" Artibus Asiae 18.2 (1955, pp. 161-177) p 166.

- ↑ Ptolemy's information appears to come at several removes from a Han guide of the first century CE, according to Phillips (Phillips 1955:170); it would have been translated from Persian to Greek by the traveller Maes Titianus for his itinerary, used by Marinus of Tyre as well as Ptolemy.

- ↑ Golden, Peter (1992). An Introduction of the Turkic Peoples: Ethnogenesis and State Formation in Medieval and Early Modern Asia and the Middle East. O. Harrassowitz. ISBN 3-447-03274-X. p. 51

- ↑ Bolton, J.D.P. (1962). Aristeas of Proconnesus. pp. 104–118.

- ↑ Under "Issedones".

- ↑ As Herodotus tells us (IV.26): "The Issedonians are said to have these customs: when a man's father is dead, all the relations bring cattle to the house, and then having slain them and cut up the flesh, they cut up also the dead body of the father of their entertainer, and mixing all the flesh together they set forth a banquet." Similar practices obtained among the Massagetae (Herodotus I.217) and the Scythians (Plato, Euthydemus 299, Strabo 298), Phillips notes, mentioning "similar customs in medieval Tibet" (Phillips 1955:170).

- ↑ Natural History by Pliny Book VI/Chapter 7

- ↑ Natural History by Pliny Book VI/Chapter 19