Gondophares

| Author:Laxman Burdak, IFS (R) |

Gondophares was the founder of the Indo-Parthian Kingdom and its most prominent king, ruling from 19 to 46.

Variants

- Gondophares I

- Greek: Γονδοφαρης Gondopharēs, Υνδοφερρης Hyndopherrēs;

- Kharosthi: 𐨒𐨂𐨡𐨥𐨪 Gu-da-pha-ra, Gudaphara;[1]

- 𐨒𐨂𐨡𐨥𐨪𐨿𐨣 Gu-da-pha-rna, Gudapharna;[2]

- 𐨒𐨂𐨡𐨂𐨵𐨪 Gu-du-vha-ra, Guduvhara[3]

Etymology

The name of Gondophares was not a personal name, but an epithet derived from the Middle Iranian name 𐭅𐭉𐭍𐭃𐭐𐭓𐭍, Windafarn (Parthian), and 𐭢𐭥𐭭𐭣𐭯𐭥, Gundapar (Middle Persian), in turn derived from the Old Iranian name 𐎻𐎡𐎭𐎳𐎼𐎴𐎠 (Vindafarnâ, "May he find glory" (cf. Greek Ἰνταφέρνης, Intaphernes)),[4] which was also the name of one of the six nobles that helped the Achaemenid king of kings (shahanshah) Darius the Great (r. 522 BC – 486 BC) to seize the throne.[5][6] In old Armenian, it is "Gastaphar". "Gundaparnah" was apparently the Eastern Iranian form of the name.[7]

Ernst Herzfeld claims his name is perpetuated in the name of the Afghan city Kandahar, which he founded under the name Gundopharron.[8]

According to a historical perspective to the Persian literature, Gondophares is identical with Fariborz of Iranian national narratives. The name of "Fariborz" (فریبرز) was written by Abu Ali Bal'ami and Al-Tabari as "Borzāfrah" (بُرزافره) and Ibn Balkhi as "Zarāfah" (زَرافَه). The author of Mojmal al-Tawarikh wrote the name as "Borzfari" (بُرزفَری) and stated that Ferdowsi changed it to "Fariborz" to keep the rhythmic structure of meter.[9][10]

History

Buddha Prakash[11] mentions that in the chaos of Bactrian Greek kings and their struggles the Parthians or Pahlavas, particularly Gondophares, conquered the Panjab and, in alliance with the Kushana chief Kujula Kadphises, liquidated the Greeks who tried to raise their heads under Hermaeus.

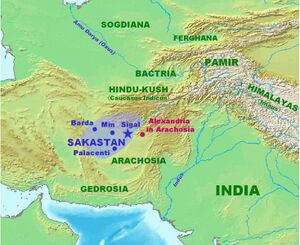

He probably belonged to a line of local princes who had governed the Parthian province of Drangiana since its disruption by the Indo-Scythians in c. 129 BC, and may have been a member of the House of Suren. During his reign, his kingdom became independent from Parthian authority and was transformed into an empire, which encompassed Drangiana, Arachosia, and Gandhara.[12][6] He is generally known from the Acts of Thomas, the Takht-i-Bahi inscription, and silver and copper coins bearing his visage.

He was succeeded in Drangiana and Arachosia by Orthagnes, and in Gandhara by his nephew Abdagases I.[13][14]

Background

Gondophares may have been a member of the House of Suren, one of the most esteemed families in Arsacid Iran, that not only had the hereditary right to lead the royal military, but also to place the crown on the Parthian king at the coronation.[15] In c. 129 BC, the eastern portions of the Parthian Empire, primarily Drangiana, was invaded by nomadic peoples, mainly by the Eastern Iranian Saka (Indo-Scythians) and the Indo-European Yuezhi, thus giving the rise to the name of the province of Sakastan ("land of the Saka").[16][17]

The ruler of the Parthian Empire ruler Mithridates II (124–88 BCE) vanquished the Sakas of the region of Sakastan, and established "Satraps" in the region, one of them probably being Tanlis Mardates. These Parthian satraps ruled over Sakastan until the establishment of the dynasty of Gondophares (19-46 CE).[18]

As a result of these invasions, the Suren family was may have been given control of Sakastan in order to defend the empire from further nomad incursions; the Surenids not only may have managed to repel the Indo-Scythians, but also to invade and seize their lands in Arachosia and Punjab, thus resulting in the establishment of the Indo-Parthian Kingdom.[19]

Rule

Gondophares ascended the throne in c. 19 or c. 20, and quickly declared independence from the Parthian Empire, minting coins in Drangiana where he assumed the Greek title of autokrator ("one who rules by himself").[20]

Gondophares I has traditionally been given a later date; the reign of one king calling himself Gondophares has been established at 20 AD by the rock inscription he set up at Takht-i-Bahi near Mardan, Pakistan, in 46 AD.,[21] and he has also been connected with the third-century Acts of Thomas.

Gondophares I took over the Kabul valley and the Punjab and Sindh region area from the Scythian king Azes. In reality, a number of vassal rulers seem to have switched allegiance from the Indo-Scythians to Gondophares I. His empire was vast, but was only a loose framework, which fragmented soon after his death. His capital was the Gandharan city of Taxila.[22]Taxila is located in Punjab to the west of the present Islamabad.

References

- ↑ Gardner, Percy, The Coins of the Greek and Scythic Kings of Bactria and India in the British Museum, p. 103-106

- ↑ Alexander Cunningham, Coins of the Sakas, The Numismatic Chronicle and Journal of the Numismatic Society, Third Series, Vol. 10 (1890), pp. 103-172; Gardner, Percy, The Coins of the Greek and Scythic Kings of Bactria and India in the British Museum, p. 105

- ↑ Konow, Sten, Kharoshṭhī Inscriptions with the Exception of Those of Aśoka, Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, Vol. II, Part I. Calcutta: Government of India Central Publication Branch, p. 58

- ↑ W. Skalmowski and A. Van Tongerloo, Middle Iranian Studies: Proceedings of the International Symposium Organized by the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven from the 17th to the 20th of May 1982, p. 19

- ↑ Bivar, A. D. H. (2002). "GONDOPHARES". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XI, Fasc. 2. pp. 135–136.

- ↑ Gazerani, Saghi (2015). The Sistani Cycle of Epics and Iran's National History: On the Margins of Historiography. BRILL. pp. 1–250. ISBN 9789004282964. p.23

- ↑ Mary Boyce and Frantz Genet, A History of Zoroastrianism, Leiden, Brill, 1991, pp.447–456, n.431

- ↑ Ernst Herzfeld, Archaeological History of Iran, London, Oxford University Press for the British Academy, 1935, p.63.

- ↑ Kalani, Reza. 2022. Indo-Parthians and the Rise of Sasanians, Tahouri Publishers, Tehran, p375

- ↑ https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/fariborz-son-of-key-kavus

- ↑ Buddha Prakash: Evolution of Heroic Tradition in Ancient Panjab, X. The Struggle with the Yavanas, Sakas and Kushanas, p.98

- ↑ Rezakhani, Khodadad (2017). ReOrienting the Sasanians: East Iran in Late Antiquity. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 1–256. ISBN 9781474400305. p. 35.

- ↑ Rezakhani 2017, p. 37.

- ↑ Gazerani, Saghi (2015). The Sistani Cycle of Epics and Iran's National History: On the Margins of Historiography. BRILL. pp. 1–250. ISBN 9789004282964.,p.25

- ↑ Bivar 2002, pp. 135–136.

- ↑ Frye, Richard Nelson (1984). The History of Ancient Iran. C.H.Beck. pp. 1–411. ISBN 9783406093975. The history of ancient iran. p. 193.

- ↑ Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (1997). "Sīstān". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Lecomte, G. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume IX: San–Sze. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 681–685. ISBN 978-90-04-10422-8. pp. 681–685.

- ↑ Rezakhani 2017, p. 32, "The coinage of a series of authorities whose names are given as Tanlis, Tanlis Mardates, and probably a queen named Rangodeme are quite likely to be the last series issued by these ‘satraps’ before the establishment of the dynasty of Gondophares in Sistan and Arachosia. The early rulers of Sakistan/Sistan can thus be characterised as Arsacid governors, possibly of Saka origin, who are appointed following the defeat of the Sakas in the region by Mithridates II".

- ↑ Bivar 2002, pp. 135–136.

- ↑ Gazerani 2015, pp. 24–25.

- ↑ A. D. H. Bivar, "The History of Eastern Iran", in Ehsan Yarshater (ed.), The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol.3 (1), The Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanian Periods, London, Cambridge University Press, 1983, p.197.

- ↑ B. N. Puri, "The Sakas and Indo-Parthians", in A.H. Dani, V. M. Masson, Janos Harmatta, C. E. Boaworth, History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Motilal Banarsidass Publ., 2003, Chapter 8, p.196

Back to General History