Saka

Saka or Sakas is the name used in Middle Persian and Sanskrit sources for the Scythians, a large group of Eurasian nomads on the Eurasian Steppe speaking Eastern Iranian languages.[1][2][3] Modern scholars usually use the term Saka to refer to Iranians of the Eastern Steppe and the Tarim Basin.[4]

Jat Gotras Namesake

- Saka = Sacæ (Pliny.vi.19)

- Saka (Scythian Jats): Damoh rose to importance in the 14th century. The inscription discovered at Batiagadh of the year V.S. 1385 (1328 AD) records Muslims as Sakas. It mentions Muhammad Tuglak. It tells us that Delhi was also known by the name Yoginipura.[5]This historic town was the erstwhile headquarters of the Khojas before the center of power was transferred to Damoh. The Khojas had the regional administrative center of the Chanderi province at Batihadim (Batiagarh) which was transferred to Damova (Damoh).

- Shaka (शक) (Jat clan) - Shakendra (शकेन्द्र). Shakendra (शकेन्द्र) is is mentioned in Verse-3 of No.9. Batihagarh stone Inscription Samvat 1385 (1328 AD)[6].... (V.3) In the Kali (age) there was a King, the Shaka-Lord (शकेन्द्र), the ruler of the earth, who having established himself in Yoginipura (योगिनीपुर) (Delhi) ruled the whole earth.

- Saka (Jat clan) → Sakour is a village in Hata tahsil in Damoh district of Madhya Pradesh.

- Saka (Scythian Jats) → Sakour is a village in Hata tahsil in Damoh district of Madhya Pradesh. (119) Sakaur Pilgrim Record of 1304 AD[7] tells us ....Sakaur is a village 9 miles from Hata. It has a flat roofed Gupta Temple, on the roof stone of which there is a pilgrim record of much later date samvat 1361 (=1304 AD). In this village many Gupta gold coins were found.[8]

- Saka (Scythian Jats) → Sakari is a village in Batiagarh tahsil in Damoh district of Madhya Pradesh.

Mention by Pliny

Pliny[9] mentions The nations of Scythia and the countries on the Eastern Ocean..... Beyond this river (Jaxartes) are the peoples of Scythia. The Persians have called them by the general name of Sacæ,1 which properly belongs to only the nearest nation of them. The more ancient writers give them the name of Aramii. The Scythians themselves give the name of "Chorsari" to the Persians, and they call Mount Caucasus Graucasis, which means "white with snow."

1 The Sacæ probably formed one of the most numerous and most powerful of the Scythian Nomad tribes, and dwelt to the east and north-east of the Massagetæ, as far as Servia, in the steppes of Central Asia, which are now peopled by the Kirghiz Cossacks, in whose name that of their ancestors, the Sacæ, is traced by some geographers.

Variants of name

- Śaka/Shaka (Sanskrit:शक)

- Saca

- Sakā (Persian old), mod. ساکا

- Σάκαι Sákai (Ancient Greek)

- Sacae (Latin)

- 塞 (Chinese old) Sək, mod. Sāi

- Sakai (Pliny the Elder)

- Saka suni (Saka or Scythian sons)

- Scythians

- Indo-Scythians

- Sakaraulai

Mention by Panini

Shaka (शक) is mentioned by Panini in Ashtadhyayi under Shandikadi (शंडिकादि) (4.3.92) group.[10]

Shaka-Yavanam (शक-यवनम) is mentioned by Panini in Ashtadhyayi. [11]

History

René Grousset wrote that they formed a particular branch of the "Scytho-Sarmatian family" originating from nomadic Iranian peoples of the northwestern steppe in Eurasia.[12] They migrated into Sogdia and Bactria in Central Asia and then to the northwest of the Indian subcontinent where they were known as the Indo-Scythians. In the Tarim Basin and Taklamakan Desert region of Northwest China, they settled in Khotan and Kashgar which were at various times vassals to greater powers, such as Han China and Tang China.

Modern debate about the identity of the "Saka" is partly from ambiguous usage of the word by ancient, non-Saka authorities.

According to Herodotus, the Persians gave the name "Saka" to all Scythians.[13]

Pliny the Elder (Gaius Plinius Secundus, AD 23–79) claims that the Persians gave the name Sakai only to the Scythian tribes "nearest to them".[14]

The Scythians to the far north of Assyria were also called the Saka suni (Saka or Scythian sons) by the Persians. The Neo-Assyrian Empire of the time of Esarhaddon record campaigning against a people they called in the Akkadian the Ashkuza or Ishhuza.[15]

However, modern scholarly consensus is that the Eastern Iranian language ancestral to the Pamir languages in North India and the medieval Saka language of Xinjiang, was one of the Scythian languages.[16]

Another people, the Gimirrai,[17] who were known to the ancient Greeks as the Cimmerians, were closely associated with the Sakas. In Biblical Hebrew, the Ashkuz (Ashkenaz) are considered to be a direct offshoot from the Gimirri (Gomer).[18]

The Saka were regarded by the Babylonians as synonymous with the Gimirrai; both names are used on the trilingual Behistun Inscription, carved in 515 BC on the order of Darius the Great.[19] (These people were reported to be mainly interested in settling in the kingdom of Urartu, later part of Armenia, and Shacusen in Uti Province derives its name from them.[20]) The Behistun Inscription initially only gave one entry for saka, they were however further differentiated later into three groups:[13][14][15]

- the Sakā tigraxaudā – "Saka with pointy hats/caps",

- the Sakā haumavargā – interpreted as "haoma-drinking saka" but there are other suggestions,[21][22][23]

- the Sakā paradraya – "Saka beyond the sea", a name added after Darius' campaign into Western Scythia north of the Danube.[24]

An additional term is found in two inscriptions elsewhere:[25]

- the Sakā para Sugdam – "Saka beyond Sugda (Sogdia)", a term was used by Darius for the people who formed the limits of his empire at the opposite end to Kush (the Ethiopians), therefore should be located at the eastern edge of his empire.[26][27]

- The Sakā paradraya were the western Scythians (European Scythians) or Sarmatians. Both the Sakā tigraxaudā and Sakā haumavargā are thought to be located in Central Asia east of the Caspian Sea.[28]

- Sakā haumavargā is considered to be the same as Amyrgians, the Saka tribe in closest proximity to Bactria and Sogdia. It has been suggested that the Sakā haumavargā may be the Sakā para Sugdam, therefore Sakā haumavargā is argued by some to be located further east than the Sakā tigraxaudā, perhaps at the Pamir Mountains or Xinjiang, although Syr Darya is considered to be their more likely location given that the name says "beyond Sogdia" rather than Bactria.[29]

In the modern era, the archaeologist Hugo Winckler (1863–1913) was the first to associate the Sakas with the Scyths. John Manuel Cook, in The Cambridge History of Iran, states: "The Persians gave the single name Sakā both to the nomads whom they encountered between the Hunger steppe and the Caspian, and equally to those north of the Danube and Black Sea against whom Darius later campaigned; and the Greeks and Assyrians called all those who were known to them by the name Skuthai (Iškuzai). Sakā and Skuthai evidently constituted a generic name for the nomads on the northern frontiers."[30]

Persian sources often treat them as a single tribe called the Saka (Sakai or Sakas), but Greek and Latin texts suggest that the Scythians were composed of many sub-groups.[31][32]

Modern scholars usually use the term Saka to refer to Iranian-speaking tribes who inhabited the Eastern Steppe and the Tarim Basin.[33][34]

Greek and Persian History

The Saka people were an Iranian people who spoke a language belonging to the Iranian branch of the Indo-European languages. They are known to the ancient Greeks as Scythians and are attested in historical and archaeological records dating to around the 8th century BC.[35]

In the Achaemenid-era Old Persian inscriptions found at Persepolis, dated to the reign of Darius I (r. 522-486 BC), the Saka are said to have lived just beyond the borders of Sogdia. Likewise an inscription dated to the reign of Xerxes I (r. 486-465 BC) has them coupled with the Dahae people of Central Asia. The contemporary Greek historian Herodotus noted that the Achaemenid Empire called all of Scythians as "Saka".[36]

Greek historians wrote of the wars between the Saka and the Medes, as well as their wars against Cyrus the Great of the Persian Achaemenid Empire where Saka women were said to fight alongside their men.[37] According to Herodotus, Cyrus the Great confronted the Massagetae, a people related to the Saka,[38] while campaigning to the east of the Caspian Sea and was killed in the battle in 530 BC.[39] Darius I also waged wars against the eastern Sakas, who fought him with three armies led by three kings according to Polyaenus.[40] In 520–519 BC, Darius I defeated the Sakā tigraxaudā tribe and captured their king Skunkha (depicted as wearing a pointed hat in Behistun).[41] The territories of Saka were absorbed into the Achaemenid Empire as part of Chorasmia that included much of the Amu Darya (Oxus) and the Syr Darya (Jaxartes),[42] and the Saka then supplied the Achaemenid army with large number of mounted bowmen.[43]

They were also mentioned as among those who resisted Alexander the Great's incursions into Central Asia.[44]

Sakas in the Ili valley and Bactria

The Saka were known as the Sak or Sai (Chinese: 塞) in ancient Chinese records.[45][46] These records indicate that they originally inhabited the Ili and Chu River valleys of modern Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan. In the Book of Han, the area was called the "land of the Sak", i.e. the Saka.[47] The exact date of the Sakas' arrival in the valleys of the Ili and Chu in Central Asia is unclear, perhaps it was just before the reign of Darius I.[48] Around 30 Saka tombs in the form of kurgans (burial mounds) have also been found in the Tian Shan area dated to between 550–250 BC. Indications of Saka presence have also been found in the Tarim Basin region, possibly as early as the 7th century BC.[49]

The Saka were pushed out of the Ili and Chu River valleys by the Yuezhi, thought by some to be Tocharians. An account of the movement of these people is given in Sima Qian's Records of the Grand Historian. The Yuezhi, who originally lived between Tängri Tagh (Tian Shan) and Dunhuang of Gansu, China,[50] were assaulted and forced to flee from the Hexi Corridor of Gansu by the forces of the Xiongnu ruler Modu Chanyu, who conquered the area in 177-176 BC.[51][52] In turn the Yuezhi were responsible for attacking and pushing the Sai (i.e. Saka) west into Sogdiana, where around 140 and 130 BC the latter crossed the Syr Darya into Bactria. The Saka also moved southwards towards to the Pamirs and northern India where they settled in Kashmir, and eastwards to settle in some of the oasis city-states of Tarim Basin sites like Yanqi (焉耆, Karasahr) and Qiuci (龜茲, Kucha).[53][54] The Yuezhi, themselves under attacks from another nomadic tribe the Wusun in 133-132 BC, moved again from the Ili and Chu valleys and occupied the country of Daxia (大夏, "Bactria").[55][56]

The ancient Greco-Roman geographer Strabo noted that the four tribes that took down the Bactrians in the Greek and Roman account – the Asioi, Pasianoi, Tokharoi and Sakaraulai – came from land north of the Syr Darya where the Ili and Chu valleys are located.[57][58] Identification of these four tribes varies, but Sakaraulai may indicate an ancient Saka tribe, the Tokharoi is possibly the Yuezhi, and while the Asioi had been proposed to be groups such as the Wusun or Alans.[59][60]

Grousset wrote of the migration of the Saka: "the Saka, under pressure from the Yueh-chih (Yuezhi), overran Sogdiana and then Bactria, there taking the place of the Greeks." Then, "Thrust back in the south by the Yueh-chih," the Saka occupied "the Saka country, Sakastana, whence the modern Persian Seistan."[61] According to Harold Walter Bailey, the territory of Drangiana (now in Afghanistan and Pakistan) became known as "Land of the Sakas", and was called Sakastāna in the Persian language of contemporary Iran, in Armenian as Sakastan, with similar equivalents in Pahlavi, Greek, Sogdian, Syriac, Arabic, and the Middle Persian tongue used in Turfan, Xinjiang, China.[62] This is attested in a contemporary Kharosthi inscription found on the Mathura lion capital belonging to the Saka kingdom of the Indo-Scythians (200 BC - 400 AD) in North India,[63] roughly the same time the Chinese record that the Saka had invaded and settled the country of Jibin 罽賓 (i.e. Kashmir, of modern-day India and Pakistan).[64]

Migrations of the 2nd and 1st century BC have left traces in Sogdia and Bactria, but they cannot firmly be attributed to the Saka, similarly with the sites of Sirkap and Taxila in ancient India. The rich graves at Tillya Tepe in Afghanistan are seen as part of a population affected by the Saka.[65]

The Shakya clan of India, to which Gautama Buddha, called Śākyamuni "Sage of the Shakyas", belonged, has been suggested to be Sakas by Michael Witzel[66] and Christopher I. Beckwith.[67]

Indo-Scythians

Main article: Indo-Scythians

The region in modern Afghanistan and Pakistan where the Saka moved to become known as "land of the Saka" or Sakastan.[68] The Sakas also captured Gandhara and Taxila, and migrated to North India.[69] An Indo-Scythians kingdom was established in Mathura (200 BC - 400 AD).[70] Weer Rajendra Rishi, an Indian linguist, identified linguistic affinities between Indian and Central Asian languages, which further lends credence to the possibility of historical Sakan influence in North India.[71].[72] According to historian Michael Mitchiner, the Abhira tribe were a Saka people cited in the Gunda inscription of the Western Satrap Rudrasimha I dated to 181 CE.[73]

Kingdom of Khotan

The Kingdom of Khotan was a Saka city state in on the southern edge of the Tarim Basin. As a consequence of the Han–Xiongnu War spanning from 133 BCE to 89 CE, the Tarim Basin (now Xinjiang, Northwest China), including Khotan and Kashgar, fell under Han Chinese influence, beginning with the reign of Emperor Wu of Han (r. 141-87 BC).[74][75] The region once again came under Chinese suzerainty with the campaigns of conquest by Emperor Taizong of Tang (r. 626-649).[76] From the late eighth to ninth centuries, the region changed hands between the rival Tang and Tibetan Empires.[52][53] However, by the early 11th century the region fell to the Muslim Turkic peoples of the Kara-Khanid Khanate, which led to both the Turkification of the region as well as its conversion from Buddhism to Islam. A document from Khotan written in Khotanese Saka, part of the Eastern Iranian branch of the Indo-European languages, listing the animals of the Chinese zodiac in the cycle of predictions for people born in that year; ink on paper, early 9th century

Archaeological evidence and documents from Khotan and other sites in the Tarim Basin provided information on the language spoken by the Saka.[77][78] The official language of Khotan was initially Gandhari Prakrit written in Kharosthi, and coins from Khotan dated to the 1st century bear dual inscriptions in Chinese and Gandhari Prakrit, indicating links of Khotan to both India and China.[79] Surviving documents however suggest that an Iranian language was used by the people of the kingdom for a long time Third-century AD documents in Prakrit from nearby Shanshan record the title for the king of Khotan as hinajha (i.e. "generalissimo"), a distinctively Iranian-based word equivalent to the Sanskrit title senapati, yet nearly identical to the Khotanese Saka hīnāysa attested in later Khotanese documents. This, along with the fact that the king's recorded regnal periods were given as the Khotanese kṣuṇa, "implies an established connection between the Iranian inhabitants and the royal power," according to the Professor of Iranian Studies Ronald E. Emmerick. He contended that Khotanese-Saka-language royal rescripts of Khotan dated to the 10th century "makes it likely that the ruler of Khotan was a speaker of Iranian." Furthermore, he argued that the early form of the name of Khotan, hvatana, is connected semantically with the name Saka.[80]

Later Khotanese-Saka-language documents, ranging from medical texts to Buddhist literature, have been found in Khotan and Tumshuq (northeast of Kashgar).[81] Similar documents in the Khotanese-Saka language dating mostly to the 10th century have been found in the Dunhuang manuscripts.[82]

Although the ancient Chinese had called Khotan Yutian (于闐), another more native Iranian name occasionally used was Jusadanna (瞿薩旦那), derived from Indo-Iranian Gostan and Gostana, the names of the town and region around it, respectively.[83]

Sakas in Mahabharata

Shaka (शक) have been mentioned in mentioned in various verses of Mahabharata (II.47.19),(II.47.26),(II.48.15),(III.48.20),(V.19.21),(V.158.20),(VI.10.43), (VI.10.50), (VI.20.13),(VI.52.7), (VIII.51.18),

Shakas brought Tributes to Yudhishthira:

Sabha Parva, Mahabharata/Book II Chapter 47 mentions the Kings who brought tributes to Yudhishthira. ....Sakas were mentioned in verse (II.47.19) with other tribes, bringing tribute to Yudhishthira. Numberless Chinas and Sakas and Uddras and many barbarous tribes living in the woods, and many Vrishnis and Harahunas, and dusky tribes of the Himavat, and many Nipas and people residing in regions on the sea-coast, waited at the gate. [84]

Sabha Parva, Mahabharata/Book II Chapter 47 mentions the Kings who brought tributes to Yudhishthira. ....Sakas were again mentioned in verse (II.47.26)....And the Sakas and and Tukharas and Kankas and Romas and men with horns bringing with them as tribute numerous large elephants and ten thousand horses, and hundreds and hundreds of millions of gold waited at the gate. [85]

Sabha Parva, Mahabharata/Book II Chapter 48 mentions the Kings who brought tributes to Yudhishthira. ....Sakas were again mentioned in verse (II.48.15,16).... the Kukkuras, the Sakas, the Angas, the Vangas, the Pundras, the Sanavatyas, and the Gayas --these good and well-born (Sujata) Kshatriyas distributed into regular clans and trained to the use of arms, brought tribute unto king Yudhishthira by hundreds and thousands. [86]

subjection by Nakula and Bhima: Nakula the son of Pandu reduced to subjection the fierce Mlechchas residing on the sea coast, as also the wild tribes of the Palhavas, the Kiratas, the Yavanas, and the Sakas (2:31).

Bhima subjugated strategically the Sakas and the barbarians living in that part of the country. And the son of Pandu, sending forth expeditions from Videha, conquered the seven kings of the Kiratas living about the Indra mountain. (2:29). These Sakas seems to be established in the north-east regions of Gangatic plain. These Sakas close to Videha was mentioned at (6:9) in the list of kingdoms of Bharata Varsha (Ancient India). Another colony of Sakas were mentioned close to the Nishadha Kingdom in central India.

In the Rajasuya sacrifice of Yudhisthira:

Vana Parva, Mahabharata/Book III Chapter 48 describes Rajasuya sacrifice of Yudhisthira attended by the chiefs of many islands and countries....Sakas were mentioned in verse (III.48.20)....and all the kings of the West by hundreds, and all the chiefs of the sea-coast, and the kings of the Pahlavas and the Daradas and the various tribes of the Kiratas and Yavanas and Sakas [87]....

Udyoga Parva/Mahabharata Book V Chapter 19 mentions the Kings and tribes Who joined Yudhishthira for Kurukshetra war. ...Sakas were mentioned in verse (V.19.21)....And Sudakshina, Kambojas, Yavanas and Sakas, came to the Kuru chief with an Akshauhini of troops.[88]

Udyoga Parva/Mahabharata Book V Chapter 158 tells..."Sanjaya said, 'Having reached the Pandava camp, the gambler's son (Uluka) presented himself before the Pandavas, and addressing Yudhishthira....Sakas were mentioned in verse (V.158.20)........swarming with the kings of the East, West, South, and North, with Kambojas, Sakas, Khasas, Shalwas, Matsyas, Kurus of the middle country, Mlechchhas, Pulindas, Dravidas, Andhras, and Kanchis, indeed, with many nations, all addressed for battle, is uncrossable like the swollen tide of Ganga.[89]

The Provinces of Sakas:

Bhisma Parva, Mahabharata/Book VI Chapter 10 describes geography and provinces of Bharatavarsha....Sakas Province mentioned in verse (VI.10.43)........the Adirashtras, the Sukattas, the Balirashtras, the Kevalas, the Vanarasyas, the Paravahas, the Vakras, the Vakrabhayas, the Sakas; [90]

Bhisma Parva, Mahabharata/Book VI Chapter 10 describes geography and provinces of Bharatavarsha....Sakas Province again mentioned in verse (VI.10.50)........the Sakas, the Nishadas, the Nishadhas, the Anartas, the Nairitas, the Dugulas, the Pratimatshyas, the Kushala, the Kunatals, and

[91]

The preparation of Mahabharata War:

Bhisma Parva, Mahabharata/Book VI Chapter 20 describes Warriors in Bhisma's division...Sakas are mentioned in verse (VI.20.13)........And Saradwat's son, that fighter in the van, that high-souled and mighty bowman, called also Gautama and Chitrayudha, conversant with all modes of warfare, accompanied by the Sakas, the Kiratas, the Yavanas, and the Pahlavas, took up his position at the northern point of the army. [92]

Bhisma Parva, Mahabharata/Book VI Chapter 52 describes the order of army of the (Kuru) in Mahabharata War....Sakas are mentioned in verse (VI.52.7)........And Vinda and Anuvinda of Avanti, and the Kambojas with the Sakas, and the Surasenas, O sire, formed its tail [93]

Karna Parva/Mahabharata Book VIII Chapter 51 describes terrible massacre on seventeenth day of Mahabharata War....Sakas are mentioned in verse (VIII. 51.18).......Of terrible deeds and exceedingly fierce, the Tusharas, the Yavanas, the Khasas, the Darvabhisaras, the Daradas, the Sakas, the Kamathas, the Ramathas, the Tanganas the Andhrakas, the Pulindas, the Kiratas of fierce prowess, the Mlecchas, the Mountaineers, and the races hailing from the sea-side...have met with destruction.[94]

They were also vanquished by Krishna:- The Sakas, and the Yavanas with followers, were all vanquished by Krishna. (7:11).

In Kurukshetra War: Words of Satyaki a commander in the side of Pandavas:- I shall have to encounter the Sakas endued with prowess equal to that of Sakra (Indra) himself, who are fierce as tire, and difficult to put out like a blazing conflagration (7:109).

In Kurukshetra War, the Sakas sided with the Kauravas under the Kamboja king Sudakshina.

Saka king was reckoned by Drupada in his list of kings to be summoned for the cause of Pandavas in Kurukshetra War (5:4). Sudakshina, the king of the Kambhojas, accompanied by the Yavanas and Sakas, came to the Kuru chief with an Akshauhini of troops (5:19). The Sakas, the Kiratas, and Yavanas, the Sivis and the Vasatis with their Maharathas at the heads of their respective divisions joined the Kaurava army (5:198). The Sakas, the Kiratas, and Yavanas, and the Pahlavas, took up his position at the northern point of the army (6:20).

Of terrible deeds and exceedingly fierce, the Tusharas, the Yavanas, the Khasas, the Darvabhisaras, the Daradas, the Sakas, the Kamathas, the Ramathas, the Tanganas the Andhrakas, the Pulindas, the Kiratas of fierce prowess, the Mlecchas, the Parvatas, and the races hailing from the sea-side, all endued with great wrath and great might, delighting in battle and armed with maces, these all united with the Kurus (8:73).

Yavanas were armed with bow and arrows and skilled in smiting. They were followed by Sakas and Daradas and Barbaras and Tamraliptakas, and other countless Mlecchas (7:116). Three thousand bowmen headed by Duryodhana, with a number of Sakas and Kamvojas and Valhikas and Yavanas and Paradas, and Kalingas and Tanganas and Amvashtas and Pisachas and Barbaras and Parvatas, inflamed with rage and armed with stone, all rushed against Satyaki (7:118).

Sakas were mentioned along with other tribes like the Sudras, the Abhiras, the Daserakas, the Yavanas, the Kamvojas, the Hangsapadas, the Paradas, the Vahlikas, the Samsthanas, the Surasenas, the Venikas, the Kukkuras, the Rechakas, the Trigartas, the Madrakas, the Tusharas and the Chulikas as battling on the side of Kauravas at various passages. (6:51,75,88, 7:20,90).

A number of Saka and Tukhara and Yavana horsemen, accompanied by some of the foremost combatants among the Kambojas, quickly rushed against Arjuna (8:88). All the Samsaptakas, the Kambojas together with the Sakas, the Mlecchas, the Parvatas, and the Yavanas, have also been slain by Arjuna (9:1)

Sakas after Kurukshetra War: A passage which is rendered as a futuristic prediction in Mahabharata mentions thus:- The Sakas, the Pulindas, the Yavanas, the Kamvojas, the Valhikas and the Abhiras, will then become possessed of bravery and the sovereignty of the whole earth (3:187).

Sakadwipa

Sakadwipa: - Bhisma Parva, Mahabharata/Book VI Chapter 12 writes about Sakadwipa. Mahabharata mentions about a whole region inhabited by Sakas called Sakadwipa to the north-west of ancient India. Sakadwipa is surrounded on all sides by the ocean. There are seven mountains that are decked with jewels and that are mines of gems, precious stones. These were - 1. Meru, 2. Malaya, 3. Jaladhara, 4. Raivataka, 5.Syama (Dark Mountain), 6. Durgasaila, 7. Kesari.

There are seven Varshas in that island corresponding to each mountain - 1. Mahakasa of Meru, 2. Kumudottara of Malaya, 3. Sukumara of Jaladhara , 4. Kaumara of Raivataka, 5. Manikanchana of Syama, 6. Mahapuman of Durgasaila, 7. Mandaki of Kesari.

In the midst of that island is a large tree called Saka.

The rivers there are full of sacred water, these are - 1. Ganga, 2. Sukumari, 3. Kumari, 4. Seta, 5. Keveraka, 6. Mahanadi, 7. Manijala, 8. Chakshus, 9. Vardhanika.

There, in that region of Saka, are four sacred provinces. They are 1. Mrigas, 2.Masakas, 3. Manasas, and 4. Mandagas. The Mrigas for the most part are Brahmanas devoted to the occupations of their order. Amongst the Masakas are virtuous Kshatriyas. The Manasas live by following the duties of the Vaishya order. Having every wish of theirs gratified, they are also brave and firmly devoted to virtue and profit. The Mandagas are all brave Shudras of virtuous behaviour.

There in that region are, many delightful provinces where Siva is worshipped, and thither repair the Siddhas, the Charanas, and the Devas. The people there are virtuous, and all the four orders are devoted to their respective occupation. No instance of theft can be seen there. Freed from decrepitude and death and gifted with long life, the people there grow like rivers during the season of rains.

In these provinces there is no king, no punishment, no person that deserves to be punished. Conversant with the dictates of duty they are all engaged in the practice of their respective duties and protect one another. This much is capable of being said of the region called Saka.

The region called Sakadwipa is mentioned again at (12:14) as a region to the east of the great Meru mountains.

Jat History

Prof. B.S. Dhillon[95]Jats writes....Jats are the one component of a group of people known as the Scythians in the Western countries and Sakas in India. Diodorus (first century B.C.) [96] wrote, "But now, in turn, we shall discuss the Scythians who inhabit the country bordering India. But some time later the descendants (Scythians) of these kings, because of their unusual valour and skill as generals, subdued much of the territory beyond the Tanais river (far eastern Europe) as far as Thrace (modern north of Greece), and advancing with their power as far as the Nile in Egypt. This people increased to great strength and had notable kings, one of whom gave his name to the Sacae (Sakas), another to the Massagetae ("great" Jats), another to the Arimaspi, and several other tribes". The recent edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica [97] states "The Scythians were a people who during the 8th-7th centuries B.C. moved from Central Asia to Southern Russia, where they founded an empire that survived until they were gradually overcome and supplanted by the Sarmatians (another Scythian people) during the 4th century B.C. 2nd century A.D.".

Hukum Singh Panwar (Pauria)[98] writes that: Here we refer again to Varahamihira who gives somatometric traits or anthropometrical description of five great men Hansa, Sasa, Rucaka, Bhadra and Malavya to serve as specimen.

Hukum Singh Panwar (Pauria)[99] writes that: Sasa, (Sese, Sse, Saso, Sasaka, Sakas), slightly projecting and thin teeth, thin nails, large eyeballs, fleshy cheek, too much narrow and slender waist, not very stout, age 70 years and is said to be a border-chief (Pratyantika) or vassal (Mandalika) with height, span and girth of 99 angulas or 72.9 inches each.

During first century A.D., Aspavarman, son of Vijayamitra and grandson of Indravardhan is said to have been the Viceroy of Azes II in a district of north-western India but later served under Gondopharnes, followed by his nephew Sasa, who later served Pacores successor of Gandopharnes190. Most probably the Sasa family Was from Indo-Parthian who were undoubtedly a section of the Scythians, who were also known as Sasa, Sese, Sse, Sasak or Sakas in history. Even row the Jats call the north-western frontier people as Sasse and Khakkhai (Afghans and Pathans). Prof. E.J. Rapson191 refers to a number of Sasa Strategoi (senapatis), the suffixes like 'Varman' and 'Daua 'in whose names show that they were Hinduised Saka chiefs under the Parthian rulers of N.W. India. Interestingly, there are Shak, Sakwan, Saklan, Sheshwan, Madra-Maderna, Mall, Malli and Hans gotras (tribes) in the Jats as well as Ros or Rosai (Rucak) in them. The Sasas may be later Sasodias.

Identification of Jats with the Sakas

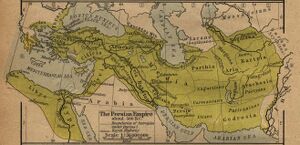

Bhim Singh Dahiya[100] writes...Reference is invited to the map[101] facing this page. The only change that we have made in this map is to give the names of the rivers and the seas which were not given in the original. In this map the Sakas are shown above Alexandria and north of Sogdiana and to the east of Massagetae and the Aral Sea. Between the Aral Sea and the Caspian Sea, are shown the Dahae. Scythians are shown on the Danube and the Don rivers, towards west of the Black Sea. There is general agreement amongst the historians that the Indo-Iranian Sakas and the European Scythians were the same. The classical Greek writers mention the Sakas as Sakai and Sacae. Ptolemy mentions them as Indo-Scythians after their arrival in India. H.H. Wilson mentions the same in his commentary on the Vishnu Purana. Writing about the Jats of pre-partition Punjab, Hewitt says, "Their very name connects them with the Getae of Thrace and hence with the Guttons said by Pytheas to live on the southern shores of the Baltic, the Guttons placed by Ptolemy and Tacitus, on the Vistula in the country of Lithuanians, and the Goths of Gothland in Sweden. This Scandinavian descent is confirmed by their system of land tenure called Bhayyāchārā." [102] This proof of custom is very important, because this Bhayyāchārā or Bhāichārā system is exclusively a Jat system, and is not found anywhere else. Further the Indo-Scythians, the Kusanas, etc. are known to shave their heads, a custom still prevalent among the Indian Jats who have not adopted Sikhism. Again, the rule of primogeniture was never followed by the Jats and there is conclusive evidence that the Scythians also divided their assets equally among all the sons. According to Herodotus, among the races of Thrace (modern Bulgaria), the Getae were the bravest and most upright. They were fond of music. They had an old custom of appointing family genealogists and thus perpetuating the history of their race and tribe in the form of mythic genealogy. This custom is very familiar to, and still practised by,

[p.27]: the Jats in India. The Pandas/Bhatas from Hardwar, Mathura, etc. or the Mirasis, even now record the genealogy of the Jats and recite it, sitting on the housetops on important occasions of the particular family. We have mentioned a few identical customs in order to meet the objection that a similarity of names is no proof of identity.

Now back to the citations of authority. According to The Historians' History of the World [103], Scythians was the name of those tribes of central Asia and northern Europe who always invaded their neighbouring races. Scythia is described as an ancient country which extended from the east of the Caspian Sea and the valley of rivers Jihon and Sihon (Amu Darya & Sir Darya) to the rivers Danube and the Dan. They invaded Greece and occupied Athens. They are named by Homer and the Hesiod. Known as milkdrinkers, warfare was their profession. Thucydides says that they were so many in numbers and so dreadful, that if they were united, they were irresistible. Diodorus says that Massa-Getae were the descendants of Scythians. This shows that the Scythians/Sakas were spread from the west of the Black Sea to the east of the Aral Sea. Alongwith the Sakas, the Massagetae are shown, in the map (as residing in 500 B.C.) on the Aral Sea on its eastern side. Dahae are shown as inhabiting the regions to the south of the Aral Sea and east of the Caspian Sea. Though these tribes are shown separately under different names, they are from the same race, i.e., Jat race. Dahae, also mentioned in the Vishnu Purana, are the modern Dahiya Jats in India. They are the same as Dahae of Ptolemy and the Tahia (Dahia) of the Chinese.[104]

Natalya Romanovna Guseva also considered the Jats to be the descendants of the Sakas.[105]

Descent of the Sakas from Narishyant

Hukum Singh Panwar (Pauria)[106] writes....The Puranas[107], Pargiter[108], Pandey[109] Shafer[110], and Pusalker93 also corroborate the descent of the Sakas from Narishyant. According to Wilson, as already noted, these very Sakas (Scythians) were the Haihayas of James Tod. Archaeological evidence and the descent of the Sakas from the Aiksvaka Aryan king Narishyant of the Solar race of Vaisali, indisputably attest that they were Aryans, and this is recognised by Kephart, C.V. Vaidya and others also. They were expelled by Sagar to north western countries after their defeat at Ayodhya where they, in league with the Yadus, Worsted Bahu, father of Sagar, in a previous battle.

Scythians, Indo–Scythians, and Sakas

Encyclopedia Wikipedia states,

- "Though closely related, the Sakas are to be distinguished from the Scythians of the Pontic Steppe and the Massagetae of the Aral Sea region, although they form part of the wider Scythian cultures. Like the Scythians, the Sakas were ultimately derived from the earlier Andronovo culture. Their language formed part of the Scythian languages. Prominent archaeological remains of the Sakas include Arzhan, Tunnug, the Issyk kurgan, Saka Kurgan tombs, the Barrows of Tasmola and possibly Tillya Tepe.

- In the 2nd century BC, many Sakas were driven by the Yuezhi from the steppe into Sogdia and Bactria and then to the northwest of the Indian subcontinent, where they were known as the Indo-Scythians. Other Sakas invaded the Parthian Empire, eventually settling in Sistan, while others may have migrated to the Dian Kingdom in Yunnan, China. In the Tarim Basin and Taklamakan Desert region of Northwest China, they settled in Khotan, Yarkand, Kashgar and other places, which were at various times vassals to greater powers, such as Han China and Tang China."

किपिन

विजयेन्द्र कुमार माथुर[111] ने लेख किया है ...किपिन (AS, p.189) चीन के प्राचीन इतिहास-लेखकों ने भारत के इस प्रदेश का कई बार उल्लेख किया है.चीनी इतिहास सीन हानशू (Thien Han Schu) के अनुसार साइवांग या शक नामक जाति यूचियों (यूची=ऋषिक) द्वारा अपने निवास स्थान से निकाल दिए जाने पर दक्षिण में आकर किपिन देश में राज्य करने लगी (दे. जर्नल ऑफ एशियाटिक सोसायटी 1903, पृ. 22) सिल्वनलेवी के मत में किपिन कश्मीर ही का चीनी नाम है किंतु स्टेनकोनो के अनुसार कपिश या पूर्वी गंधार को चीनी लेखकों ने किपिन कहा है (देखें एपिग्राफिक इंडिका 16, पृ. 291). चीनी यात्री सुंगयुन ने भी किपिन का उल्लेख किया है. किपिन कुभा (=काबुल) का रूपांतर भी हो सकता है.

शकस्थान

विजयेन्द्र कुमार माथुर[112] ने लेख किया है कि....शकस्थान शकों का मूल निवास स्थान था जो ईरान के उत्तर-पश्चिमी भाग तथा परिवर्ती प्रदेश में स्थित था. इसे सीस्तान कहा जाता है. शकस्थान का उल्लेख महा-मायूरि 95, मथुरा सिंहस्तंभ-लेख कदंम्बनरेश मयूरशर्मन् के चंद्रवल्ली प्रस्ताव लेख में है. मथुरा-अभिलेख के शब्द हैं-- 'सर्वस सकस्तनस पुयेइ' जिसका अर्थ, कनिंघम के अनुसार 'शकस्तान निवासियों के पुण्यार्थ' है. राय चौधरी (पॉलीटिकल हिस्ट्री ऑफ अनसियन्ट इंडिया, पृ. 526) के मत में शकस्तान ईरान में स्थित था और शकवंशीय चष्टन और रुद्रदामन के पूर्व पुरुष गुजरात-काठियावाड़ में इसी स्थान से आकर बसे थे.

शकों का उल्लेख रामायण ('तैरासीत् संवृताभूमि: शकैर्यवनमिश्रितै:' बालकांड 54,21; 'कांबोजययवनां श्चैव-शकानांपत्तनानिच' किष्किंधा 23,12 महाभारत ('पहलवान् बर्बरांश्चैव किरातान् यवनाञ्छकान्' सभापर्व 32,17); मनुस्मृति (पौण्ड्रकाश्चौड्रद्रविड़ा:कांबोजा यवना: शका:"' 10,44 तथा महाभाष्य (देखें इंडियन एंटिक्ववेरी 1857,पृ.244) आदि ग्रंथों में है.

शकवंश

शकवंश - वैदिक सम्पत्ति लेखक पं० रघुनंदन शर्मा ने पृ० 424 पर लिखा है कि वैवस्वत मनु के इक्ष्वाकु, नरिष्यन्त (नरहरि) आदि 10 पुत्र हुए। इस लेखक ने विष्णु पुराण एवं हरिवंश का हवाला देकर लिखा है कि नरिष्यन्त के पुत्रों का ही नाम शक है। इनकी प्रसिद्धि से इनके नाम पर क्षत्रिय आर्यों का संघ शकवंश कहलाया जो कि एक जाटवंश है। सम्राट् सगर ने अपने पिता बाहु की हार का बदला शत्रुओं को हराकर इस तरह से लिया कि उसने शकों, पारदों, यवनों और पह्लवों को अपने देश से निकाल दिया। शक लोगों ने आर्यावर्त से बाहर जाकर एक देश आबाद किया जो कि इनके नाम से शकावस्था कहलाया जिसका अपभ्रंश नाम सीथिया पड़ गया।[113]

सीथिया तथा मध्य एशिया में शक जाट

दलीप सिंह अहलावत[114] के उपरोक्त विवरण अनुसार शक जाटों के नाम पर सीथिया देश नाम पड़ा। |महाभारत युद्ध के बाद इन लोगों का राज्य सीथिया तथा मध्य एशिया में लिखा गया है।

इतिहासकारों की यह समान राय है कि इण्डो-ईरानियन शक और यूरोपियन सीथियनज़ एक ही थे। उच्चकोटि के यूनानी इतिहासकारों ने शक लोगों को सकाई और सकाय लिखा है।

जाट वीरों का इतिहास: दलीप सिंह अहलावत, पृष्ठान्त-345

लेखक पटोलेमी ने इन लोगों को भारत में आने के बाद इण्डो-सीथियन लिखा है।

सीथिया एक प्राचीन देश था जो कि कैस्पियन सागर और अमू दरिया एवं सिर दरिया की घाटी से लेकर डेन्यूब व डॉन नदियों के मध्यवर्ती देशों तक फैला हुआ था। सीथियन मध्य एशिया और उत्तरी यूरोप की उन जातियों का नाम था जिन्होंने सदा अपनी पड़ौसी जातियों पर आक्रमण किए (हिस्टोरियनज़ हिस्ट्री ऑफ दी वर्ल्ड, वाल्यूम II, P. 400)

इन सीथियन (शक) लोगों ने यूनान पर आक्रमण किया और एथन्स पर अधिकार कर लिया। इन लोगों के विषय में इतिहासकार होमर और हेसीउड ने भी लिखा है कि वे लोग दूध पीने वाले थे तथा युद्ध इनका व्यवसाय था। यूनानी प्रसिद्ध इतिहासज्ञ थूसीडाईड्स ने इन सीथियन जाटों के विषय में लिखा है कि “एशिया अथवा यूरोप में कोई भी जाति (राष्ट्र) नहीं थी जो सीथियन जाटों के मुकाबले में खड़ी रह सके।” (अनटिक्विटी ऑफ जाट रेस पृ० 47 लेखक उजागरसिंह माहिल)

थूसीडाईड्स लिखता है कि “इनकी संख्या इतनी अधिक थी तथा वे बहुत ही भयानक थे कि यदि जब भी वे संयुक्त हो जाते थे तब उनको कोई भी नहीं रोक सका।” इसी प्रकार से यूनान के प्रसिद्ध इतिहासज्ञ हैरोडोटस, जिसको इतिहास का पिता कहा गया है, तथा अन्य इतिहासकारों के कथन अनुसार “जाटों में जब भी एकता हुई तब संसार की कोई भी जाति बहादुरी में इनका मुकाबला नहीं कर सकी।” इतिहासज्ञ डीउडोरुस (Diodorus) लिखता है कि “मस्सागेटाई लोग सीथियनज़ के ही वंशज थे। सीथियन/शक लोग काला सागर के पश्चिम से लेकर अरल सागर के पूर्व तक फैले हुए थे। थ्रेश देश में जो कि सीथिया देश का एक प्रान्त था (आज का बुल्गारिया), वहां पर गेटे (जाटों) का शासन था।” हैरोडोटस लिखता है कि [Thrace|थ्रेस]] की जातियों में जाट लोग सबसे अधिक बहादुर तथा ईमानदार थे। वे गाने-बजाने के प्रेमी थे। वे अन्य जातियों में सबसे श्रेष्ठ एवं न्यायकारी थे[115]।

बी० सी० अग्रवाल ने इण्डिया अज़् नोन् टु पाणिनि पृ० 68-69” पुस्तक का हवाला देकर लिखा है कि “बहुत से शक कबीले (जातियां) आज भी जाटों में पाये जाते हैं। शक लोग पाणिनि ऋषि के समय से पहले भारतवर्ष में आये और इनकी दूसरी लहर दूसरी शताब्दी ईस्वी पूर्व में भारत में आई और इसके पश्चात् कुषाण लोग आये। मध्य एशिया के शक लोगों ने वापी या रहट (Stepped Well) तथा अरघट्टा (Persian wheel) का निर्माण किया। स्थानों या नगरों के नाम जिनके अन्त में कन्द लगता है वे सब शक लोगों ने आरम्भ किए जैसे - समरकन्द, ताशकन्द, यारकन्द आदि।” (H.W. Bailey, ASLCA, Transaction of Philological Society, 1945, PP 22, 33)

जाटों का यूरोप की ओर बढ़ना

ठाकुर देशराज[116] ने लिखा है .... हूणों के आक्रमण के समय जगजार्टिस और आक्सस नदियों के किनारे तथा कैस्पियन सागर के तट पर बसे हुए जाट यूरोप की ओर बढ़ गए। एशियाई देशों में जिस समय हूणों का उपद्रव था, उसी समय यूरोप में जाट लोगों का

[पृ.154]: धावा होता है। कारण कि आंधी की भांति उठे हुए हूणों ने जाटों को उनके स्थानों से उखाड़ दिया था। जाट समूहों ने सबसे पहले स्केंडिनेविया और जर्मनी पर कब्जा किया। कर्नल टॉड, मिस्टर पिंकर्टन, मिस्टर जन्स्टर्न, डिगाइन, प्लीनी आदि अनेक यूरोपियन लेखकों ने उनका जर्मनी, स्केंडिनेविया, रूम, स्पेन, गाल, जटलैंड और इटली आदि पर आक्रमण करने का वर्णन किया है। इन वर्णनों में में कहीं उन्हें, जेटा, कहीं जेटी, और कहीं गाथ नाम से पुकारा है। क्योंकि विजेता जाटों के यह सारे समूह ईरान और का कैस्पियन समुद्र के किनारे से यूरोप की ओर बढ़े थे। इसीलिए यूरोपीय देशों में उन्हें शक व सिथियन के नाम से भी याद किया गया है। ईरान को शाकद्वीप कहते हैं। इसीलिए इरान के निवासी शक कहलाते थे। यूरोपियन इतिहासकारों का कहना है कि जर्मनी की जो स्वतंत्र रियासतें हैं, और जो सैक्सन रियासतों के नाम से पुकारी जाती हैं। इन्हीं शक जाटों की हैं। वे रियासतें विजेता जाटों ने कायम की थी। हम यह मानते हैं और यह भी मानते हैं कि वे जाट शाकद्वीप से ही गए थे। किंतु यूरोपियन लेखकों के दिमाग में इतना और बिठाना चाहते हैं कि शाल-द्वीप में वे जाट भारत से गए थे। और वे उन खानदानों में से थे जो राम, कृष्ण और यदु कुरुओं के कहलाते हैं।

यूरोप में जाने वाले जाटों ने राज्य तो कायम किए ही थे साथ ही उन्होंने यूरोप को कुछ सिखाया भी था। प्रातः बिस्तरे

[पृ.155]: से उठकर नहाना, ईश्वर आराधना करना, तलवार और घोड़े की पूजा, शांति के समय खेती करना,भैंसों से काम लेना यह सब बातें उन्होंने यूरोप को सिखाई थी। कई स्थानों पर उन्होंने विजय स्तंभ भी खड़े किए थे। जर्मनी में राइन नदी के किनारे का उनका स्तंभ काफी मशहूर रहा था।

भारत माता के इन विजयी पुत्रों ने यूरोप में जाकर भी बहुत काल तक वैदिक धर्म का पालन किया था। किंतु परिस्थितियों ने आखिर उन्हें ईसाई होने पर बाध्य कर ही दिया। यदि भारत के धर्म प्रचारक वहां पहुंचते रहते तो वह हरगिज ईसाई ना होते। किंतु भारत में तो सवा दो हजार वर्ष से एक संकुचित धर्म का रवैया रहा है जो कमबख्त हिंदूधर्म के नाम से मशहूर है। उनकी रस्म रिवाजों और समारोहों के संबंध में जो मैटर प्राप्त होता है उसका सारांश इस प्रकार है:-

- जेहून और जगजार्टिस नदी के किनारे के जाट प्रत्येक संक्रांति पर बड़ा समारोह किया करते थे।

- विजयी अटीला जाट सरदार ने एलन्स के किले में बड़े समारोह के साथ खङ्ग पूजा का उत्सव मनाया था।

- जर्मनी के जाट लंबे और ढीले कपड़े पहनते थे और सिर के बालों की एक बेणी बनाकर गुच्छे के समान मस्तक के ऊपर बांध लेते थे।

- स्केंडिनेविया की शिवि और शैवी जाट हरगौरी और धरतीमाता की पूजा किया करते थे। उत्सव पर वे हरिकुलेश और बुद्ध की प्रशंसा के गीत गाते हैं।

- उनके झंडे पर बलराम के हल का चित्र था। युद्ध में वे शूल (बरछे) और मुग्दर (गदा) को काम में लाते थे।

- वे विपत्ति के समय अपनी स्त्रियॉं की सम्मति को बहुत महत्व देते थे।

- उनकी स्त्रियां प्रायः सती होने को अच्छा समझती थी।

- वे विजिट लोगों को गुलाम नहीं मानते थे। उनकी अच्छी बातों को स्वीकार करने में वे अपनी हेटी नहीं समझते थे।

- लड़ाई के समय वे ऐसा ख्याल करते थे कि खून के खप्पर लेकर योगनियां रणक्षेत्र में आती हैं।

बहादुर जाटों के ये वर्णन जहां प्रसन्नता से हमारी छाती को फूलाते हैं वहां हमें हृदय भर कर रोने को भी बाध्य करते हैं। शोक है उन जगत-विजेता वीरों की कीर्ति से भी जाट जगत परिचित नहीं है।

References

- ↑ "Scythian, also called Scyth, Saka, and Sacae, member of a nomadic people, originally of Iranian stock." Scythian-Saka

- ↑ Sakas: In Afghanistan at Encyclopædia Iranica"The ethnonym Saka appears in ancient Iranian and Indian sources as the name of the large family of Iranian nomads called Scythians by the Classical Western sources and Sai by the Chinese (Gk. Sacae; OPers. Sakā)."

- ↑ Yarkand at Encyclopædia Iranica "The territory of Yārkand is for the first time mentioned in the Hanshu (1st century BCE), under the name Shache (Old Chinese, approximately, *s³a(j)-ka), which is probably related to the name of the Iranian Saka tribes."

- ↑ Beckwith, Christopher (8 May 2011). Empires of the Silk Road (PDF). Princeton University Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-0691150345.

- ↑ Aitihasik Sthanavali by Vijayendra Kumar Mathur, p.602

- ↑ Epigraphia Indica & Record of the Archaeological Survey of India, Volume XII, 1913-14, p. 44-46. Ed by Sten Konow, Published by Director General Archaeological Survey of India, 1982.

- ↑ Inscriptions in the Central Provinces and Berar by Rai Bahadur Hira Lal, Nagpur, 1932, p.63

- ↑ Hiralal's Damoh Dipaka, 2nd edition, page 107,108

- ↑ Natural History by Pliny Book VI/Chapter 19

- ↑ V. S. Agrawala: India as Known to Panini, 1953, p.511

- ↑ V. S. Agrawala: India as Known to Panini, 1953, p.78

- ↑ Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 29–31. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.

- ↑ Herodotus Book VII, 64

- ↑ Naturalis Historia, VI, 19, 50

- ↑ Westermann, Claus (1984). : A Continental Commentary. John J. Scullion (trans.). Minneapolis. p. 506. ISBN 0800695003.

- ↑ Kuz'mina, Elena E. (2007). The Origin of the Indo Iranians. Edited by J.P. Mallory. Leiden, Boston: Brill, pp 381-382. ISBN 978-90-04-16054-5.

- ↑ Westermann, Claus (1984). : A Continental Commentary. John J. Scullion (trans.). Minneapolis. p. 506. ISBN 0800695003.

- ↑ Ashkenaz in Young, Robert. Analytical Concordance to the Bible. McLean, Virginia: Mac Donald Publishing Company.

- ↑ George Rawlinson, noted in his translation of History of Herodotus, Book VII, p. 378

- ↑ Kurkjian, Vahan M. (1964). A History of Armenia. New York: Armenian General Benevolent Union of America. p. 23.

- ↑ J. M. Cook (6 June 1985). "The Rise of the Achaemenids and Establishment of Their Empire". In Ilya Gershevitch. The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 2. Cambridge University Press; Reissue edition. pp. 253–255. ISBN 978-0521200912.

- ↑ M. A. Dandamayev. History of Civilizations of Central Asia Volume II: The development of sedentary and nomadic civilizations: 700 BC to AD 250. UNESCO. pp. 44–46. ISBN 978-8120815407.

- ↑ "Haumavargā". Encyclopedia Iranica.

- ↑ J. M. Cook (6 June 1985). "The Rise of the Achaemenids and Establishment of Their Empire". In Ilya Gershevitch. The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 2. Cambridge University Press; Reissue edition. pp. 253–255. ISBN 978-0521200912.

- ↑ The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume IV. Cambridge University Press. 24 November 1988. p. 173. ISBN 978-0521228046.

- ↑ J. M. Cook (6 June 1985). "The Rise of the Achaemenids and Establishment of Their Empire". In Ilya Gershevitch. The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 2. Cambridge University Press; Reissue edition. pp. 253–255. ISBN 978-0521200912.

- ↑ Briant, Pierre (29 July 2006). From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire. Eisenbrauns. p. 178. ISBN 978-1575061207. "This is Kingdom which I hold, from the Scythians [Saka] who are beyond Sogdiana, thence unto Ethiopia [Cush]; from Sind, thence unto Sardis."

- ↑ J. M. Cook (6 June 1985). "The Rise of the Achaemenids and Establishment of Their Empire". In Ilya Gershevitch. The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 2. Cambridge University Press; Reissue edition. pp. 253–255. ISBN 978-0521200912.

- ↑ J. M. Cook (6 June 1985). "The Rise of the Achaemenids and Establishment of Their Empire". In Ilya Gershevitch. The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 2. Cambridge University Press; Reissue edition. pp. 253–255. ISBN 978-0521200912.

- ↑ J. M. Cook (6 June 1985). "The Rise of the Achaemenids and Establishment of Their Empire". In Ilya Gershevitch. The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 2. Cambridge University Press; Reissue edition. pp. 253–255. ISBN 978-0521200912.

- ↑ Ireland, Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and (2007-04-06). Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society ... – Google Books.

- ↑ ournal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland By Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland-page-323

- ↑ Beckwith, Christopher (8 May 2011). Empires of the Silk Road (PDF). Princeton University Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-0691150345.

- ↑ L. T. Yablonsky (2010-06-15). "The Archaeology of Eurasian Nomads". In Donald L. Hardesty. ARCHAEOLOGY – Volume I. EOLSS. p. 383. ISBN 9781848260023.

- ↑ J. P. mallory. "Bronze Age Languages of the Tarim Basin" (PDF). Penn Museum. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-09-09.

- ↑ Bailey, H.W. (1996) [14 April 1983]. "Chapter 34: Khotanese Saka Literature". In Ehsan Yarshater. The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol III: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian Periods, Part 2 (reprint ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 1230–1231. ISBN 978-0521246934.

- ↑ L. T. Yablonsky (2010-06-15). "The Archaeology of Eurasian Nomads". In Donald L. Hardesty. ARCHAEOLOGY – Volume I. EOLSS. p. 383. ISBN 9781848260023.

- ↑ Barbara A. West (2010-05-19). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. p. 516. ISBN 9781438119137.

- ↑ Cunliffe, Barry (24 September 2015). By Steppe, Desert, and Ocean: The Birth of Eurasia. Oxford University Press. p. 206. ISBN 978-0199689170.

- ↑ A. Sh. Shahbazi,. "Amorges". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- ↑ Beckwith, Christopher (8 May 2011). Empires of the Silk Road (PDF). Princeton University Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-0691150345.

- ↑ Cunliffe, Barry (24 September 2015). By Steppe, Desert, and Ocean: The Birth of Eurasia. Oxford University Press. p. 235. ISBN 978-0199689170.

- ↑ M. A. Dandamayev. History of Civilizations of Central Asia Volume II: The development of sedentary and nomadic civilizations: 700 BC to AD 250. UNESCO. pp. 44–46. ISBN 978-8120815407.

- ↑ L. T. Yablonsky (2010-06-15). "The Archaeology of Eurasian Nomads". In Donald L. Hardesty. ARCHAEOLOGY – Volume I. EOLSS. p. 383. ISBN 9781848260023.

- ↑ Zhang Guang-da. History of Civilizations of Central Asia Volume III: The crossroads of civilizations: AD 250 to 750. UNESCO. p. 283. ISBN 978-8120815407.

- ↑ H. W. Bailey. Indo-Scythian Studies: Being Khotanese Texts. Cambridge University Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0521118736.

- ↑ Yu Taishan (June 2010), "The Earliest Tocharians in China" in Victor H. Mair (ed), Sino-Platonic Papers, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, University of Pennsylvania Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, p. 13.

- ↑ Yu Taishan (June 2010), "The Earliest Tocharians in China" in Victor H. Mair (ed), Sino-Platonic Papers, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, University of Pennsylvania Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, p. 13.

- ↑ J. P. mallory. "Bronze Age Languages of the Tarim Basin" (PDF). Penn Museum. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-09-09.

- ↑ Mallory, J. P. & Mair, Victor H. (2000). The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West. Thames & Hudson. London. p. 58. ISBN 0-500-05101-1.

- ↑ Torday, Laszlo. (1997). Mounted Archers: The Beginnings of Central Asian History. Durham: The Durham Academic Press, pp 80-81, ISBN 978-1-900838-03-0.

- ↑ Chang, Chun-shu. (2007). The Rise of the Chinese Empire: Volume II; Frontier, Immigration, & Empire in Han China, 130 B.C. – A.D. 157. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, pp 5-8 ISBN 978-0-472-11534-1.

- ↑ Yu Taishan (June 2010), "The Earliest Tocharians in China" in Victor H. Mair (ed), Sino-Platonic Papers, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, University of Pennsylvania Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, pp. 13-14, 21-22.

- ↑ Benjamin, Craig. "The Yuezhi Migration and Sogdia".

- ↑ Yu Taishan (June 2010), "The Earliest Tocharians in China" in Victor H. Mair (ed), Sino-Platonic Papers, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, University of Pennsylvania Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, p. 13.

- ↑ Bernard, P. (1994). "The Greek Kingdoms of Central Asia". In Harmatta, János. History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume II. The development of sedentary and nomadic civilizations: 700 B.C. to A.D. 250. Paris: UNESCO. pp. 96–126. ISBN 92-3-102846-4.

- ↑ Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 29–31. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.

- ↑ Yu Taishan (June 2010), "The Earliest Tocharians in China" in Victor H. Mair (ed), Sino-Platonic Papers, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, University of Pennsylvania Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, p. 13.

- ↑ Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 29–31. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.

- ↑ Baumer, Christoph (30 November 2012). The History of Central Asia: The Age of the Steppe Warriors. I.B.Tauris. p. 296. ISBN 978-1780760605.

- ↑ Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 29–31. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.

- ↑ Bailey, H.W. (1996) [14 April 1983]. "Chapter 34: Khotanese Saka Literature". In Ehsan Yarshater. The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol III: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian Periods, Part 2 (reprint ed.). Cambridge

- ↑ Bailey, H.W. (1996) [14 April 1983]. "Chapter 34: Khotanese Saka Literature". In Ehsan Yarshater. The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol III: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian Periods, Part 2 (reprint ed.). Cambridge

- ↑ Ulrich Theobald. (26 November 2011). "Chinese History - Sai 塞 The Saka People or Soghdians." ChinaKnowledge.de.

- ↑ Yaroslav Lebedynsky, P. 84

- ↑ Attwood, Jayarava (2012). "Possible Iranian Origins for the Śākyas and Aspects of Buddhism". Journal of the Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies. 3.

- ↑ Beckwith, Christopher I. (2015). Greek Buddha: Pyrrho's Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia. Princeton University Press. p. 1–21. ISBN 978-1-4008-6632-8.

- ↑ Bailey, H.W. (1996) [14 April 1983]. "Chapter 34: Khotanese Saka Literature". In Ehsan Yarshater. The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol III: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian Periods, Part 2 (reprint ed.). Cambridge

- ↑ Sulimirski, Tadeusz (1970). The Sarmatians. Volume 73 of Ancient peoples and places. New York: Praeger. pp. 113–114.

- ↑ Bailey, H.W. (1996) [14 April 1983]. "Chapter 34: Khotanese Saka Literature". In Ehsan Yarshater. The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol III: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian Periods, Part 2 (reprint ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 1230–1231. ISBN 978-0521246934.

- ↑ Sulimirski, Tadeusz (1970). The Sarmatians. Volume 73 of Ancient peoples and places. New York: Praeger. pp. 113–114.

- ↑ Rishi, Weer Rajendra (1982). India & Russia: linguistic & cultural affinity. Roma. p. 95

- ↑ Mitchiner, Michael (1978). The ancient & classical world, 600 B.C.-A.D. 650. Hawkins Publications ; distributed by B. A. Seaby. p. 634. ISBN 978-0-904173-16-1.

- ↑ Loewe, Michael. (1986). "The Former Han Dynasty," in The Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220, 103–222. Edited by Denis Twitchett and Michael Loewe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp 197-198. ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

- ↑ Yü, Ying-shih. (1986). "Han Foreign Relations," in The Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220, 377-462. Edited by Denis Twitchett and Michael Loewe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp 410-411. ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

- ↑ Xue, Zongzheng (薛宗正). (1992). History of the Turks (突厥史). Beijing: Zhongguo shehui kexue chubanshe, p. 596-598. ISBN 978-7-5004-0432-3; OCLC 28622013

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=y7IHmyKcPtYC&pg=PA1230&lpg=PA1230#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ↑ Windfuhr, Gernot (2013). Iranian Languages. Routledge. p. 377. ISBN 1-135-79704-8.

- ↑ Emmerick, R. E. (14 April 1983). "Chapter 7: Iranian Settlement East of the Pamirs". In Ehsan Yarshater. The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol III: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian Periods, Part 1. Cambridge University Press; Reissue edition. pp. 265–266. ISBN 978-0521200929.

- ↑ Emmerick, R. E. (14 April 1983). "Chapter 7: Iranian Settlement East of the Pamirs". In Ehsan Yarshater. The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol III: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian Periods, Part 1. Cambridge University Press; Reissue edition. pp. 265–266. ISBN 978-0521200929.

- ↑ Bailey, H.W. (1996). "Khotanese Saka Literature". In Ehsan Yarshater. The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol III: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian Periods, Part 2 (reprint ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 1231–1235. ISBN 9780521246934.

- ↑ Hansen, Valerie (2005). "The Tribute Trade with Khotan in Light of Materials Found at the Dunhuang Library Cave" (PDF). Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 19: 37–46.

- ↑ Ulrich Theobald. (16 October 2011). "City-states Along the Silk Road." ChinaKnowledge.de.

- ↑ चीनान हूनाञ शकान ओडून पर्वतान्तरवासिनः, वार्ष्णेयान हारहूणांश च कृष्णान हैमवतांस तदा (II.47.19)

- ↑ शकास तुखाराः कङ्काश च रॊमशाः शृङ्गिणॊ नराः, महागमान थूरगमान गणितान अर्बुदं हयान (II.47.26)

- ↑ शौण्डिकाः कुक्कुराश चैव शकाश चैव विशां पते, अङ्गा वङ्गाश च पुण्ड्राश च शानवत्या गयास तदा (II.48.15); सुजातयः शरेणिमन्तः शरेयांसः शस्त्रपाणयः, आहार्षुः क्षत्रिया वित्तं शतशॊ ऽजातशत्रवे (II.48.16)

- ↑ पश्चिमानि च राज्यानि शतशः सागरान्तिकान, पह्लवान थरथान सर्वान किरातान यवनाञ शकान (III.48.20)

- ↑ सुदक्षिणश च काम्बॊजॊ यवनैश च शकैस तदा, उपाजगाम कौरव्यम अक्षौहिण्या विशां पते (V.19.21)

- ↑ 20 पराच्यैः परतीच्यैर अद थाक्षिणात्यैर; उदीच्यकाम्बॊजशकैः खशैश च, शाल्वैः समत्स्यैः कुरुमध्यदेशैर मलेच्छैः पुलिन्थैर थरविडान्ध्र काञ्च्यैः (V.158.20)

- ↑ आदि राष्ट्राः सुकुट्टाश च बलिराष्ट्रं च केवलम, वानरास्याः परवाहाश च वक्रा वक्रभयाः शकाः (VI.10.43)

- ↑ शका निषादा निषधास तदैवानर्तनैरृताः, दुगूलाः प्रतिमत्स्याश च कुशलाः कुनटास तदा (VI.10.50)

- ↑ शारदवतश चॊत्तरधूर महात्मा; महेष्वासॊ गौतमश चित्रयॊधी, शकैः किरातैर यवनैः पह्लवैश च; सार्धं चमूम उत्तरतॊ ऽभिपाति (VI.20.13)

- ↑ विन्थाanivinda|नुविन्थाव आवन्त्यौ काम्बॊजश च शकैः सह, पुच्छम आसन महाराज शूरसेनाश च सर्वशः

- ↑ उग्राश च करूरकर्माणस तुखारा यवनाः खशाः, दार्वाभिसारा दरदा: शका रमठ तङ्गणाः (VIII. 51.18)

- ↑ History and study of the Jats/Chapter 2, p.31

- ↑ Diodorus of Sicily (published around 49 B.C.), translated by C.H. Oldfather, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1936, pp. 27-28 (Vol. II), pp. 377, 382-383 (Vol. VIII).

- ↑ Scythians, The Encyclopaedia Britannica, The New Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., Chicago, 1984, pp. 438-442.

- ↑ The Jats:Their Origin, Antiquity and Migrations/An Historico-Somatometrical study bearing on the origin of the Jats, p.144

- ↑ The Jats:Their Origin, Antiquity and Migrations/An Historico-Somatometrical study bearing on the origin of the Jats, p.146

- ↑ Jats the Ancient Rulers (A clan study)/The Jats, pp.26-27

- ↑ Taken from D. P. Singhal's India and World Civilisation, p. 417.

- ↑ op. cit., p. 481.

- ↑ Historians' History of the World, Vol. II, p. 400.

- ↑ AIG, pp. 263-66.

- ↑ Author: Наталья Романовна Гусева (1994). Book: Индия в зеркале веков: религия, быт, культура. Publisher: Российская академия наук, Ин-т этнологии и антропологии им. Н.Н. Миклухо-Маклая. p. 49. Quote: " Саки были тем этногенетическим пластом, на основе которого сформировались джаты, составляющие и в наше время подавляющую маооу населения Пенджаба. "

- ↑ The Jats:Their Origin, Antiquity and Migrations/The Scythic origin of the Jats, p.187

- ↑ Br. Pur. 7,24; Hrv. 10,641; Ag. Pur. 272, 10; Shiv Pur., 7,60,19.

- ↑ Anc. Ind. His Tradi., pp. 206f, 256f, 267. Regmi, D.R.; Anc, Nepal,. Cal. 1969, p.158.

- ↑ Pandey, R.B.; The Puranic Data on the Original Home of the Indo-Aryans. IHQ, No. 24, 1948, pp. 94-103

- ↑ Shafer, R; Ethnography of Anc, Ind., Weisbaden, 1954. p. 16.

- ↑ Aitihasik Sthanavali by Vijayendra Kumar Mathur, p.189

- ↑ Aitihasik Sthanavali by Vijayendra Kumar Mathur, p.886

- ↑ Jat History Dalip Singh Ahlawat/Chapter IV (Pages 321-322)

- ↑ जाट वीरों का इतिहास: दलीप सिंह अहलावत, पृष्ठ.345-346

- ↑ जाट्स दी ऐनशन्ट् रूलर्ज पृ० 2, 26, 27, 302 लेखक बी० एस० दहिया।

- ↑ Thakur Deshraj: Jat Itihas (Utpatti Aur Gaurav Khand)/Navam Parichhed,p.153-156