Shakasthana

| Author:Laxman Burdak, IFS (R) |

Shakasthana (शकस्थान) means Land of the Sakas. Shakas occupied "the Shaka Country, Sakastana, whence the modern Persian Seistan."[1] The territory of Drangiana (now in Afghanistan and Pakistan) became known as "Land of the Sakas", and was called Sakastāna in the Persian language of contemporary Iran. [2]

Variants

- Shaka Sthana शकस्थान = Sistan (सीस्तान) Iran/Afghanistan (p.886)

- Sakastāna

- Sakastana

- Shaka Country

History

Sistan derives its name from 'Sakastan'. Sistan was once the homeland of Sakas, a Scythian tribe of Iranic origin. The Sakas that were once native to Sistan were driven to the Punjab during the Arsacid era (63 BCE-220 CE). The Saffarids (861-1003 CE), one of the early Iranian dynasties of the Islamic era, were originally rulers of Sistan.

Grousset wrote of the migration of the Saka: "the Saka, under pressure from the Yueh-chih (Yuezhi), overran Sogdiana and then Bactria, there taking the place of the Greeks." Then, "Thrust back in the south by the Yueh-chih," the Saka occupied "the Saka country, Sakastana, whence the modern Persian Seistan."[3] According to Harold Walter Bailey, the territory of Drangiana (now in Afghanistan and Pakistan) became known as "Land of the Sakas", and was called Sakastāna in the Persian language of contemporary Iran, in Armenian as Sakastan, with similar equivalents in Pahlavi, Greek, Sogdian, Syriac, Arabic, and the Middle Persian tongue used in Turfan, Xinjiang, China.[4] This is attested in a contemporary Kharosthi inscription found on the Mathura lion capital belonging to the Saka kingdom of the Indo-Scythians (200 BC - 400 AD) in North India,[5] roughly the same time the Chinese record that the Saka had invaded and settled the country of Jibin 罽賓 (i.e. Kashmir, of modern-day India and Pakistan).[6]

Saka the origin of different races

Hukum Singh Panwar (Pauria)[7] states:The next important discovery consequent upon our identification of the Jats is that the different races, viz., the Getae, Thyssagetae, Massagetae, Allans, Asii, Ioatii, Zanthii or Xanthii, Dahae, Parnis or Panis, Parthians, Yueh-Chihs, Ephthalites and Kushanas, etc. (who have so far been considered as separate and unrelated races by historians) are actually the offshoots of the three major sections of the Sakas, who were not a distinct race from the Aryans. The only feature where they differ in their taxonomy was their bachycephaly, a feature they they developed by residing in higher altitudes for thousands of years after their banishment or migrations from Sapta Sindhu. Their history, according to our inquiry, goes as far back as 8566 B.C. and their spread as far away as Scandinavia in Europe, and (via Alaskan Isthmus to Canada, U.S.A., Mexico, Argentina, Chile and Peru in south America besides Burma, Cambodia and Thailand in the east.

Sakadwipa and Sakasthan

Hukum Singh Panwar (Pauria)[8] states: One such starting formulation of ours is likely to shock those who have been drilled to believe that Sakas (Scythians) are not only different, but were antagonistic peoples - the Sakas (Scythians, being all that Aryans were not. We, on the contrary hold that the Ailas and Iksvakus (former's sub-section) lived side by side in the sub-Sivalik zone of the Sapta-Sindhu, where Saka trees (teak in English and Sagawan in Hindi) were grown in abundance in ancient times. The Rechna Doab in which Sakala (Sialkot) was situated was known as Sakaladwipa. The region as well as its inhabitants, derived their names from Saka, which, as some eminent anthropologists and geographers rightly hold, conveys only a geographical sense and not a racial one. The so-calico Skythia or Scythia of the Greeks, which is represented as Sakadwipa in the

The Jats:Their Origin, Antiquity and Migrations:End of page 297

ancient Indian literature, is now proved to be a misnomer: it actually stands for Sakasthan of central Asia, and not for Sakadwipa. Sakadwipa and Sakasthan are distinct, separate entities in site of similarity in sound, Sakadwipa was the landmass in the South and South east of the Meru (Pamir), the climate of which was suitable for the growth of teak; and the Sakasthan comprises the countries of adoption by the Sakas as their second home in central Asia after their exile or emigration to those countries in pre-historic times from Sapta Sindhu (cf, S.M. Ali, 1973, app., pp. 205ff). Ali has aptly vivified the distinction between the two terms.

Parthian Stations

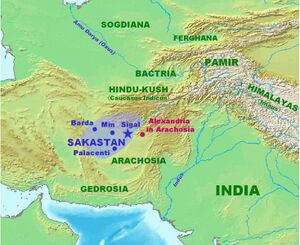

Parthian Stations by Isidore of Charax, is an account of the overland trade route between the Levant and India, in the 1st century BCE, The Greek text with a translation and commentary by Wilfred H. Schoff. Transcribed from the Original London Edition, 1914. This record mentions about city named Barda. Burdaks are probably originated from city called Barda, the place is the royal residence of the Sakas in Sistan. The presence of the Sakas in Sakastan in the 1st century BCE is mentioned by Isidore of Charax in his "Parthian stations". He explained that they were bordered at that time by Greek cities to the east (Alexandria of the Caucasus and Alexandria of the Arachosians), and the Parthian-controlled territory of Arachosia to the south:

- "Beyond is Sacastana of the Scythian Sacae, which is also Paraetacena, 63 schoeni. There are the city of Barda and the city of Min and the city of Palacenti and the city of Sigal (Cf. Nimrus of the Rustam story in the Shah Nama); in that place is the royal residence of the Sacae; and nearby is the city of Alexandria (and nearby is the city of Alexandropolis), and six villages." Parthian stations, 18.[9]

Beyond is Arachosia, 36 schoeni. And the Parthians call this White India; there are the city of Biyt and the city of Pharsana and the city of Chorochoad and the city of Demetrias; then Alexandropolis, the metropolis of Arachosia; it is Greek, and by it flows the river Arachotus. As far as this place the land is under the rule of the Parthians." Parthian stations, 19.[10]

§ 18. Sacastana of the Scythian Sacæ. This is the modern Seistan. The Sacæ, formerly residents of Central Asia, were driven out by the Yue-chi and forced across the Pamirs into Bactria. About 100 B.C. the Yue-chi followed them, overran Bactria and upper India, and established the Kushan monarchy. The Sacæ, driven before them, occupied the country around Lake Helmund, and overran the lower Indus valley, and the Cutch and Cambay coasts of Western India. They were tributary in some degree to the Parthian monarchy, and in Indian history they appear as the "Indo-Parthians." Gondophares of the Acts of St. Thomas was an Indo-Parthians prince; the Periplus, about 80 A.D., mentions his quarrelling successors in the Indus delta, and a Saka satrap, Nahapana, who established a powerful state in the Cambay district and instituted the Saka era of 78 A.D. Cf. Strabo, XI, 8, 2-5. Schoff, Periplus of the Erythræan Sea, 184-7.

In the Sháh Náma Sistán is the home of the famous family of champions, who seated the Keiánian dynasty on the throne of Persia. Their most brilliant scion was Rustam, whose matchless daring forms the main theme of Firdusi's great epic, and who is as much the national hero to-day as he was a thousand years or more ago, everything in Persia that is not understood, such as the Sassanian rock sculptures at Persepolis, being attributed to this champion, who like the Homeric heroes, was as mighty a trencherman as warrior, and almost equally respected for his prowess in both fields.

"At the period referred to above, Sagistán, as Sistán was then called, practically meant the low country to the west of Kandahár, Zabulistán being the name for the upland country, now the home of the Berbers. During the latter years of Rustam—he lived well over a century—the Persian capital was shifted from the banks of the Helmund to Fárs, and in due course history takes the place of legend.

"With regard to the historical existence of Rustam, I think we may at all events admit that there was a champion or a family of champions, who led the hosts of Iran, and furthermore, that as their history is given so circumstantially almost down to historical times, there is every probability that their exploits have a substratum of truth. Moreover, in those days, a man bigger and heavier than his adversaries, always inspired a very wholesome fear, for not only could he deal deadlier blows, but, equally important, he could carry heavier armour; in fact he was like a battleship and his opponents resembled cruisers.

"The Sarangians, mentioned by Herodotus as belonging to the 14th satrapy, occupied Sistán during the reign of Darius, and the Greek historians who narrated the conquests of Alexander the Great, gave the name of Drangiana to what is now, roughly speaking, Southern Afghanistan. This province was traversed by the world-conqueror on his way to Bactria and by Krateros on his march from Karachi to Karmania. But the most ancient traveller who actually visited and described these provinces, albeit very briefly, is Isidorus of Charax, who was a contemporary of Augustus, and whose account is of such value that I quote it in a footnote.2 We thus see that Fara and Neh were important towns, while Gari may be Girishk. Zarangia is the same as Sarangia, and includes Persian Sistán. The town of Zirra is apparently the same word which still survives in the name of the great lagoon mentioned below.

"Sakastani, or the land of the Sakæ, is evidently the same word as the Sistán of today. The Sakæ have disappeared from this part of Asia, hut I understand that the theory connecting them with the Saxons is held in certain quarters."[11] "Before entering the province of Sistán it may perhaps not be out of place to outline the various interesting historical and physical problems by which we are confronted.

"In the Sháh Náma Sistán is the home of the famous family of champions, who seated the Keiánian dynasty on the throne of Persia. Their most brilliant scion was Rustam, whose matchless daring forms the main theme of Firdusi's great epic, and who is as much the national hero to-day as he was a thousand years or more ago, everything in Persia that is not understood, such as the Sassanian rock sculptures at Persepolis, being attributed to this champion, who like the Homeric heroes, was as mighty a trencherman as warrior, and almost equally respected for his prowess in both fields.

"At the period referred to above, Sagistán, as Sistán was then called, practically meant the low country to the west of Kandahár, Zabulistán being the name for the upland country, now the home of the Berbers. During the latter years of Rustam—he lived well over a century—the Persian capital was shifted from the banks of the Helmund to Fárs, and in due course history takes the place of legend.

शकस्थान

विजयेन्द्र कुमार माथुर[12] ने लेख किया है कि....शकस्थान शकों का मूल निवास स्थान था जो ईरान के उत्तर-पश्चिमी भाग तथा परिवर्ती प्रदेश में स्थित था. इसे सीस्तान कहा जाता है. शकस्थान का उल्लेख महा-मायूरि 95, मथुरा सिंहस्तंभ-लेख कदंम्बनरेश मयूरशर्मन् के चंद्रवल्ली प्रस्ताव लेख में है. मथुरा-अभिलेख के शब्द हैं-- 'सर्वस सकस्तनस पुयेइ' जिसका अर्थ, कनिंघम के अनुसार 'शकस्तान निवासियों के पुण्यार्थ' है. राय चौधरी (पॉलीटिकल हिस्ट्री ऑफ अनसियन्ट इंडिया, पृ. 526) के मत में शकस्तान ईरान में स्थित था और शकवंशीय चष्टन और रुद्रदामन के पूर्व पुरुष गुजरात-काठियावाड़ में इसी स्थान से आकर बसे थे.

शकों का उल्लेख रामायण ('तैरासीत् संवृताभूमि: शकैर्यवनमिश्रितै:' बालकांड 54,21; 'कांबोजययवनां श्चैव-शकानांपत्तनानिच' किष्किंधा 23,12 महाभारत ('पहलवान् बर्बरांश्चैव किरातान् यवनाञ्छकान्' सभापर्व 32,17); मनुस्मृति (पौण्ड्रकाश्चौड्रद्रविड़ा:कांबोजा यवना: शका:"' 10,44 तथा महाभाष्य (देखें इंडियन एंटिक्ववेरी 1857,पृ.244) आदि ग्रंथों में है.

External links

References

- ↑ Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 29–31. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.

- ↑ Bailey, H.W. (1996) [14 April 1983]. "Chapter 34: Khotanese Saka Literature". In Ehsan Yarshater. The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol III: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian Periods, Part 2 (reprint ed.). Cambridge

- ↑ Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 29–31. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.

- ↑ Bailey, H.W. (1996) [14 April 1983]. "Chapter 34: Khotanese Saka Literature". In Ehsan Yarshater. The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol III: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian Periods, Part 2 (reprint ed.). Cambridge

- ↑ Bailey, H.W. (1996) [14 April 1983]. "Chapter 34: Khotanese Saka Literature". In Ehsan Yarshater. The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol III: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian Periods, Part 2 (reprint ed.). Cambridge

- ↑ Ulrich Theobald. (26 November 2011). "Chinese History - Sai 塞 The Saka People or Soghdians." ChinaKnowledge.de.

- ↑ The Jats:Their Origin, Antiquity and Migrations/The identification of the Jats, pp.296

- ↑ The Jats:Their Origin, Antiquity and Migrations/The identification of the Jats, pp.297-298

- ↑ Parthian stations

- ↑ Parthian stations

- ↑ [http://www.parthia.com/doc/parthian_stations.htm COMMENTARY by WILFRED H. SCHOFF]

- ↑ Aitihasik Sthanavali by Vijayendra Kumar Mathur, p.886