James Tod

| Author:Laxman Burdak, IFS (R), Jaipur |

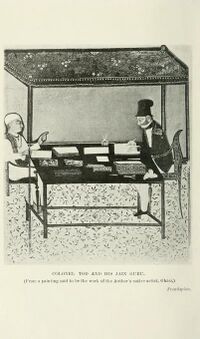

Lieutenant-Colonel James Tod (1782 – 1835) was an English-born officer of the British East India Company and an Oriental scholar. He combined his official role and his amateur interests to create a series of works about the history and geography of India, and in particular the Rajasthan.

Early life

Tod was born at Islington, London, on 20 March 1782 and educated in Scotland. He left England for India in 1799 and in doing so followed in the footsteps of various other members of his family, including his father, although Tod senior had not been in the Company but had instead owned an indigo plantation at Mirzapur.

Career

He joined the East India Company as a military officer and travelled to India in 1799 as a cadet in the Bengal Army. He rose quickly in rank, eventually becoming captain of an escort for an envoy in a Sindhian royal court. After the Third Anglo-Maratha War, during which Tod was involved in the intelligence department. He was appointed Political Agent for some areas of Rajasthan in 1818, where the British East India Company had come to amicable arrangements with the Rajput rulers in order to exert indirect control over the area.

His task was to help unify the region under the control of the East India Company. During this period Tod conducted most of the research that he would later publish. In 1823, owing to declining health and reputation, Tod resigned his post as Political Agent and returned to England.

Indian Historian

Back home in England, Tod published a number of academic works about Indian history and geography, most notably Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan, based on materials collected during his travels. He retired from the military in 1826, and married Julia Clutterbuck that same year.

Tod's major works have been criticised as containing significant inaccuracies and bias, but he is highly regarded in some areas of India, particularly in communities whose ancestors he praised. His accounts of the Rajputs and of India in general had a significant effect on British views of the area for many years.

Tod continued his surveying work in this physically-challenging, arid and mountainous area.[1] His responsibilities were extended quickly: initially involving himself with the regions of Mewar, Kota, Sirohi and Bundi, he soon added Marwar to his portfolio and in 1821 was also given responsibility for Jaisalmer.[2] These areas were considered a strategic buffer zone against Russian advances from the north which, it was feared, might result in a move into India via the Khyber Pass.

Tod believed that to achieve cohesion it was necessary that the Rajput states should contain only Rajput people, with all others being expelled. This would assist in achieving stability in the areas, thus limiting the likelihood of the inhabitants being influenced by outside forces. According to Ramya Sreenivasan, a researcher of religion and caste in early modern Rajasthan and of colonialism, Tod's "transfers of territory between various chiefs and princes helped to create territorially consolidated states and 'routinised' political hierarchies."[3][4]

One aspect of history that Tod studied in his Annals was the genealogy of the Chathis Rajkula (36 royal races), for the purpose of which he took advice on linguistic issues from a panel of pandits, including a Jain guru called Yati Gyanchandra.[5] He said that he was "desirous of epitomising the chronicles of the martial races of Central and Western India" and that this necessitated study of their genealogy. The sources for this were Puranas held by the Rana of Udaipur.[6]

Tod also submitted archæological papers to the Royal Asiatic Society's Transactions series. He was interested in numismatics as well, and he discovered the first specimens of Bactrian and Indo-Greek coins from the Hellenistic period following the conquests of Alexander the Great, which were described in his books. These ancient kingdoms had been largely forgotten or considered semi-legendary, but Tod's findings confirmed the long-term Greek presence in Afghanistan and Punjab. Similar coins have been found in large quantities since his death.[7][8]

In addition to these writings, he produced a paper on the politics of Western India that was appended to the report of the House of Commons committee on Indian affairs, 1833.[9] He had also taken notes on his journey to Bombay and collated them for another book, Travels in Western India.[10] That book was published posthumously in 1839.

Left India

In February 1823, Tod left India for England, having first travelled to Bombay by a circuitous route for his own pleasure.[11]

His last days

During the last years of his life Tod talked about India at functions in Paris and elsewhere across Europe. He also became a member of the newly established Royal Asiatic Society in London, for whom he acted for some time as librarian. He suffered an apoplectic fit in 1825 as a consequence of overwork,[12] and retired from his military career in the following year, soon after he had been promoted to lieutenant-colonel. His marriage to Julia Clutterbuck (daughter of Henry Clutterbuck) in 1826 produced three children – Grant Heatly Tod-Heatly, Edward H. M. Tod and Mary Augusta Tod – but his health, which had been poor for much of his life,[13] was declining. Having lived at Birdhurst, Croydon, from October 1828, Tod and his family moved to London three years later.

Death

He spent much of the last year of his life abroad in an attempt to cure a chest complaint and died on 18 November 1835[4] soon after his return to England from Italy. The cause of death was an apoplectic fit sustained on the day of his wedding anniversary, although he survived for a further 27 hours. He had moved into a house in Regent's Park earlier in that year.[20][25]

Tod's Works

- Tod, James (1824). "Translation of a Sanscrit Inscription, Relative to the Last Hindu King of Delhi, with Comments Thereon". Transactions of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (London: Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland) 1 (1): 133–154.

- Tod, James (1826). "Comments on an Inscription upon Marble, at Madhucarghar; And Three Grants Inscribed on Copper, Found at Ujjayani". Transactions of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (London: Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland) 1 (2): 207–229.

- Tod, James (1826). "An Account of Greek, Parthian, and Hindu Medals, Found in India". Transactions of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (London: Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland) 1 (2): 313–342.

- Tod, James (1829). "On the Religious Establishments of Mewar". Transactions of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (London: Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland) 2 (1): 270–325.

- Tod, James (1829). "Remarks on Certain Sculptures in the Cave Temples of Ellora". Transactions of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (London: Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland) 2 (1): 328–339.

- Tod, James (1829). Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan, Volume 1. London: Smith, Elder.

- Tod, James (1830). "Observations on a Gold Ring of Hindu Fabrication found at Montrose in Scotland". Transactions of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (London: Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland) 2 (2): 559–571.

- Tod, James (1831). "Comparison of the Hindu and Theban Hercules, illustrated by an ancient Hindu Intaglio". Transactions of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (London: Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland) 3 (1): 139–159.

- Tod, James (1832). Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan. Volume 2. London: Smith, Elder.

- Tod, James (1839). Travels in Western India. London: W. H. Allen.

Controversies

Criticism of the Annals came soon after publication. The anonymous author of the introduction to his posthumously published Travels states that - The only portions of this great work which have experienced anything like censure are those of a speculative character, namely, the curious Dissertation on the Feudal System of the Rajpoots, and the passages wherein the Author shows too visible a leaning towards hypotheses identifying persons, as well as customs, manners, and superstitions, in the East and the West, often on the slender basis of etymological affinities.[14]

He had to finance publication himself: sales of works on history had been moribund for some time and his name was not particularly familiar either at home or abroad.[50] Original copies are now scarce, but they have been reprinted in many editions. The version published in 1920, which was edited by the orientalist and folklorist William Crooke, is significantly editorialised.[15]

Freitag has argued that the Annals "is first and foremost a story of the heroes of Rajasthan ... plotted in a certain way – there are villains, glorious acts of bravery, and a chivalric code to uphold".[16] So dominant did Tod's work become in the popular and academic mind that they largely replaced the older accounts upon which Tod based much of his content, notably the Prithvirãj Rãjo and the Nainsi ri Khyãt.[17] Kumar Singh, of the Anthropological Survey of India, has explained that the Annals were primarily based on "bardic accounts and personal encounters" and that they "glorified and romanticised the Rajput rulers and their country" but ignored other communities.[18]

Tod reconstructed Rajput history on the basis of the ancient texts and folklore of the Rajputs. The polymath James Mill did not accept the historical validity of the native works. Tod also used philological techniques to reconstruct areas of Rajput history that were not even known to the Rajputs themselves, by drawing on works such as the religious texts known as Puranas.[19]

Tod was an officer of the British imperial system, at that time the world's dominant power. Working in India, he attracted the attention of local rulers who were keen to tell their own tales of defiance against the Mughal empire. He heard what they told him but knew little of what they omitted. He was a soldier writing about a caste renowned for its martial abilities, and he was aided in his writings by the very people whom he was documenting. He had been interested in Rajput history prior to coming into contact with them in an official capacity, as administrator of the region in which they lived. These factors, says Freitag, contribute to why the Annals were "manifestly biased".[20]

Tod relied heavily on existing Indian texts for his historical information and most of these are today considered unreliable.

Dr Natthan Singh writes regarding James Tod's bias towards Rajputs. The truth is that purohits, charans and Court poets out of greed for money and land gave prominence to Rajputs. Later, James Tod wrote annals after taking bribe from Maharaja Udaipur and Maharaja Jodhpur of the Rajputana state. He was biased towards these states and Rajputs. The earlier contributions of warriors and protectors of the land Jats, Bhils, Gujars and Meenas were neglected and lost in the history. [21]

See also

External links

- Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan, Vol.I

- Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan, Vol.II

- Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan, Vol.III

References

- ↑ Gupta, R. K.; Bakshi, S. R. (2008). Studies In Indian History: Rajasthan Through The Ages The Heritage Of Rajputs 1. New Delhi: Sarup & Sons. ISBN 81-7625-841-5., p. 132.

- ↑ Freitag, Jason (2009). Serving empire, serving nation: James Tod and the Rajputs of Rajasthan. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-17594-5, pp. 37–40

- ↑ Sreenivasan (2007), pp. 126–127.

- ↑ Peabody (1996), p. 203.

- ↑ Freitag (2009), pp. 112, 120, 164.

- ↑ Tod (1829), Vol. 1., p. 17.

- ↑ The Gentleman's Magazine (February 1836), Obituary, pp. 203–204.

- ↑ The Gentleman's Magazine (February 1836), Obituary, pp. 203–204.

- ↑ Wheeler & Stearn, (2004) Tod, James (1782–1835).

- ↑ Freitag (2009), p. 40.

- ↑ Freitag (2009), p. 40.

- ↑ Tod (1839), p. xlvii.

- ↑ Freitag (2009), p. 41.

- ↑ Tod (1839), pp. lii–liii.

- ↑ Peabody (1996), p. 187.

- ↑ Freitag (2001), p. 20.

- ↑ Freitag (2009), p. 10.

- ↑ Singh (1998), p. xvi.

- ↑ Sreenivasan (2007), pp. 130–132.

- ↑ Freitag (2009), pp. 3–5.

- ↑ Dr Natthan Singh, Jat-Itihas, (Jat History), Jat Samaj Kalyan Parishad, F-13, Dr Rajendra Prasad Colony, Tansen marg, Gwalior, M.P, India 474 002 2004, page-91

Back to Resources

Back to Jat Historians