Indica (Megasthenes)

| Author:Laxman Burdak, IFS (R) |

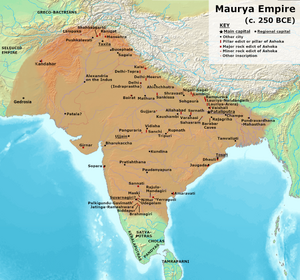

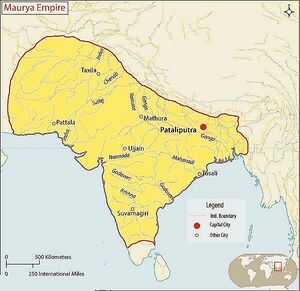

Indika (Greek: Ἰνδικά; Latin: Indica) is an account of Mauryan India by the Greek writer Megasthenes. Megasthenes (c. 350 – c. 290 BC) was an ancient Greek historian and a Greek ambassador of Seleucus I Nicator in the court of Chandragupta Maurya (321BC-298 BC).

The original work is now lost, but its fragments have survived in later Greek and Latin works. The earliest of these works are those by Diodorus Siculus, Strabo (Geographica), Pliny, and Arrian (Indica).[1][2]

Variants

Reconstruction

Megasthenes' Indica can be reconstructed using the portions preserved by later writers as direct quotations or paraphrase. The parts that belonged to the original text can be identified from the later works based on similar content, vocabulary and phrasing, even when the content has not been explicitly attributed to Megasthenes. Felix Jacoby's Fragmente der griechischen Historiker contains 36 pages of content traced to Megasthenes.[3]

E. A. Schwanbeck traced several fragments to Megasthenes, and based on his collection, John Watson McCrindle published a reconstructed version of Indica in 1887. However, this reconstruction is not universally accepted. Schwanbeck and McCrindle attributed several fragments in the writings of the 1st century BCE writer Diodorus to Megasthenes. However, Diodorus does not mention Megasthenes even once, unlike Strabo, who explicitly mentions Megasthenes as one of his sources.

There are several differences between the accounts of Megasthenes and Diodorus: for example, Diodorus describes India as 28,000 stadia (roughly 5,000 km, 3,000 miles) long from east to west; Megasthenes gives this number as 16,000 (3,000 km, 2,000 miles). Diodorus states that the Indus may be the world's largest river after the Nile; Megasthenes (as quoted by Arrian) states that the Ganges is much larger than the Nile. Historian R. C. Majumdar points out that the Fragments I and II attributed to Megasthenes in McCrindle's edition cannot originate from the same source, because Fragment I describes the Nile as larger than the Indus, while Fragment II describes the Indus as longer than the Nile and the Danube combined.[4]

Schwanbeck's Fragment XXVII includes four paragraphs from Strabo, and Schwanbeck attributes these entire paragraphs to Megasthenes. However, Strabo cites Megasthenes as his source only for three isolated statements in three different paragraphs. It is likely that Strabo sourced the rest of the text from sources other than Megasthenes: that's why he attributes only three statements specifically to Megasthenes.[5]

Another example is the earliest confirmed description of Gandaridae, which appears in the writings of Diodorus. McCrindle believed that Diodorus' source for this description was the now-lost book of Megasthenes. However, according to A. B. Bosworth (1996), Diodorus obtained this information from Hieronymus of Cardia: Diodorus described the Ganges as 30 stadia (6 km) wide; it is well-attested by other sources that Megasthenes described the median or minimum width of the Ganges as 100 stadia (20 km).[6]

Geography

According to the text reconstructed by J. W. McCrindle (1877) and Richard Stoneman (2022), Megasthenes' Indica describes India as follows:

India is a quadrilateral-shaped country, bounded by the Great Sea in the east and the south, Indus River in the west, and Emodus mountain in the north[7] ("Emodus" (or "Hemodus") refers to the Hindu Kush, Pamir, and the Himalayas taken as a single mountain range; the word is derived from the Indian term Haimavata, meaning "covered with snow".[8])

Beyond the Emodus lies the Sacae-inhabited part of Scythia.[9]

Besides Scythia, the countries of Bactria and Ariana border India.[10]

India's northern border reaches the extremities of the Tauros. From Ariana to the Eastern Sea, it is bound by mountains that are called the Kaukasos by the Macedonians. The various native names for these mountains include Parapamisos, Hemodus (or Emodus) and Himaos.[11] and the southern extremities of India as the Pandya country "occupying the portion of India which lies southward and extends to the sea".[12][13]

The area of India is said to span 28,000 stades from west to east, and 32,000 from north to south. Because of its large size, India is "thought to encompass a larger stretch of the sun's course in summer than any other part of the world". In many of the extreme points of India, a gnomon of the sundial casts no shadow, and the Bears (Ursa Major and Ursa Minor) are not visible at night. In the furthest parts, the pole star is not visible, and it is said that the shadows incline to the south.[14]

India has many large and navigable rivers, which rise in the northern mountains, and flow through the plains. Many of these rivers merge into the Ganges, which is 30 stadia wide at its source, and runs from north to south. The Ganges empties into the ocean that forms the southern boundary of Gandaridae (Gangadarai). The country of Gandaridae has the highest number and the largest elephants in India, because of which other nations are afraid of its strength, and no foreign king has been able to conquer it. Even Alexander of Macedon, who subdued all of Asia and defeated all the other Indians, refrained from making war against Gandaridae when he learned that they had 4,000 war elephants.[15]

The Indus also runs from north to south, and empties into the ocean. It has several navigable tributaries, the most notable ones being Hypanis, the Hydaspes, and the Acesines.[16] (According to a passage of Diodorus traced to Megasthenes, Indus is the world's largest river after Nile.[17] However, according to Arrian, Megasthenes as well as other writers wrote that Ganges is much larger than Indus.[18])

One peculiar river is the Sillas, which originates from a fountain of the same name. Everything cast into this river sinks down to the bottom – nothing floats in it.[19] In addition, there are a large number of other rivers, supplying abundant water for agriculture. According to the native philosophers and natural scientists, this is because the bordering countries (Scythia, Bactria, and Ariana) are more elevated than India, so their waters run down to India.[20]

History

According to the text reconstructed by J. W. McCrindle (1877) and Richard Stoneman (2022), Megasthenes' Indica describes India as follows:

In the primitive times, the Indians lived on fruits and wore clothes made of animal skin, just like the Greeks. The most learned Indian scholars say that Dionysus invaded India, and conquered it. When his army was unable to bear the excessive heat, he led his soldiers to the mountains called Meros for recovery; this led to the Greek legend about Dionysus being bred in his father's thigh (meros in Greek). D. R. Patil suggests that the Rigvedic Prithu was a vegetarian deity, associated with Greek god Dionysus.[21] Dionysus taught Indians several things including how to grow plants, make wine and worship. He founded several large cities, introduced laws and established courts. For this reason, he was regarded as a deity by the Indians. He ruled entire India for 52 years, before dying of old age. His descendants ruled India for several generations, before being dethroned and replaced by democratic city-states.[22]

The Indians who inhabit the hill country also claim that Herakles was one of them. Like the Greeks, they characterize him with the club and the lion's skin. According to them, Herakles was a powerful man who subjugated evil beasts. He had several sons and one daughter, who became rulers in different parts of his dominion. He founded several cities, the greatest of which was Palibothra (Pataliputra). Herakles built several places in this city, fortified it with water-filled trenches and settled a number of people in the city. His descendants ruled India for several generations, but never launched an expedition beyond India. After several years, the royal rule was replaced by democratic city states, although there existed a few kings when Alexander invaded India.[23]

Historical reliability

Later writers such as Arrian, Strabo, Diodorus, and Pliny refer to Indika in their works. Of these writers, Arrian speaks most highly of Megasthenes, while Strabo and Pliny treat him with less respect.

The first century Greek writer Strabo called both Megasthenes and his succeeding ambassador Deimachus liars, and stated that "no faith whatever" could be placed in their writings.[24]

The Indika contained numerous fantastical stories, such as those about tribes of people with no mouths, unicorns and other mythical animals, and gold-digging ants.[25] Strabo directly contradicted these descriptions, assuring his readers that Megasthenes' stories, along with his recounting of India’s founding by Hercules and Dionysus, were mythical with little to no basis in reality.[26] Despite such shortcomings, some authors believe that Indika is creditworthy, and is an important source of information about the contemporary Indian society, administration and other topics.[27]

According to Paul J. Kosmin, Indica served a legitimizing purpose for Seleucus I and his actions in India.[28] It depicts contemporary India as an unconquerable territory, arguing that Dionysus was able to conquer India, because before his invasion, India was a primitive rural society. Dionysus' urbanization of India makes India a powerful, impregnable nation. The later ruler — the Indian Herakles — is presented as a native of India, despite similarities with the Greek Heracles. This, according to Kosmin, is because now India is shown as unconquerable.[29] Megasthenes emphasizes that no foreign army had been able to conquer India (since Dionysus) and Indians had not invaded a foreign country either. This representation of India as an isolated, invincible country is an attempt to vindicate Seleucus' peace treaty with the Indian emperor [30] through which he abandoned territories he could never securely hold, stabilized the East, and obtained elephants with which he could turn his attention against his great western rival, Antigonus Monophthalmus. [31]

Megasthenes states that there were no slaves in India, but the Arthashastra attests to the existence of slavery in contemporary India;[32] Strabo also counters Megasthenes's claim based on a report from Onesicritus. Historian Shireen Moosvi theorizes that slaves were outcastes, and were not considered members of the society at all.[33] According to historian Romila Thapar, the lack of sharp distinction between slaves and others in the Indian society (unlike the Greek society) may have confused Megasthenes: Indians did not use large-scale slavery as a means of production, and slaves in India could buy back their freedom or be released by their master.[34]

Megasthenes mentions seven castes in India, while the Indian texts mention only four social classes (varnas). According to Thapar, Megasthenes' categorization appears to be based on economic divisions rather than the social divisions; this is understandable because the varnas originated as economic divisions. Thapar also speculates that he wrote his account some years after his visit to India, and at this time, he "arrived at the number seven, forgetting the facts as given to him". Alternatively, it is possible that the later authors misquoted him, trying to find similarities with the Egyptian society, which according to Herodotus was divided into seven social classes.[35]

Megasthenes claims that before Alexander, no foreign power had invaded or conquered Indians, with the exception of the mythical heroes Hercules and Dionysus. However, it is known from earlier sources – such as Herodotus and the inscriptions of Darius the Great – that the Achaemenid Empire included parts of north-western part of India (present-day Pakistan). It is possible that the Achaemenid control did not extend much beyond the Indus River, which Megasthenes considered to be the border of India. Another possibility is that Megasthenes intended to understate the power of the Achaemenid Empire, a rival of the Greeks.[36]

See also

References

- ↑ Upinder Singh (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India. Pearson Education India. p. 324. ISBN 9788131711200.

- ↑ Christopher I. Beckwith (2015). Greek Buddha: Pyrrho's Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia. Princeton University Press. p. 62. ISBN 9781400866328.

- ↑ Paul J. Kosmin (2013). "Apologetic Ethnography: Megasthenes' Indica and the Seleucid Elephant". In Eran Almagor, Joseph Skinner (ed.). Ancient Ethnography: New Approaches. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781472537607.

- ↑ Sandhya Jain (2011). The India They Saw (Vol-1). Ocean Books. ISBN 978-81-8430-106-9.p.22

- ↑ Sandhya Jain (2011). The India They Saw (Vol-1). Ocean Books. ISBN 978-81-8430-106-9.p.22

- ↑ A. B. Bosworth (1996). Alexander and the East. Clarendon. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-19-158945-4. pp. 188–189.

- ↑ Richard Stoneman (2022). Megasthenes' Indica: A New Translation of the Fragments with Commentary. Routledge Classical Translations. Routledge/Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781032023571.p.29

- ↑ Klaus Karttunen (2006). "Emodus". In Hubert Cancik; Helmuth Schneider (eds.). Brill's New Pauly, Antiquity volumes. doi:10.1163/1574-9347_bnp_e329930. ISBN 9789004122598.

- ↑ Richard Stoneman (2022). Megasthenes' Indica: A New Translation of the Fragments with Commentary. Routledge Classical Translations. Routledge/Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781032023571.p.29

- ↑ Richard Stoneman 2022, p. 30.

- ↑ J. W. McCrindle (1877). Ancient India As Described By Megasthenes And Arrian. London: Trübner & Co.pp.48-49

- ↑ India By John Keay

- ↑ Caldwell, Bishop R. (2004). History of Tinnevelly. Asian Educational Services. p. 15. ISBN 9788120601611.

- ↑ Richard Stoneman 2022, p. 29.

- ↑ Richard Stoneman 2022, p. 30.

- ↑ Richard Stoneman 2022, p. 30.

- ↑ Richard Stoneman 2022, p. 29.

- ↑ Richard Stoneman 2022, p. 37.

- ↑ J. W. McCrindle (1877). Ancient India As Described By Megasthenes And Arrian. London: Trübner & Co.p.35

- ↑ Richard Stoneman 2022, pp. 30–31.

- ↑ Nagendra Kumar Singh (1997). Encyclopaedia of Hinduism. Anmol Publications. pp=1714. ISBN 978-81-7488-168-7.

- ↑ J. W. McCrindle (1877). Ancient India As Described By Megasthenes And Arrian. London: Trübner & Co.pp.35-38

- ↑ J. W. McCrindle 1877, p. 39-40.

- ↑ Allan Dahlaquist (1996). Megasthenes and Indian Religion- Volume 11 of History and Culture Series. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 386. ISBN 81-208-1323-5.

- ↑ Irfan Habib; Vivekanand Jha (2004). Mauryan India. A People's History of India. Aligarh Historians Society / Tulika Books. p. 19. ISBN 978-81-85229-92-8.

- ↑ Strabo, Geography, Book XV, Chapter 1

- ↑ Irfan Habib; Vivekanand Jha (2004). Mauryan India. A People's History of India. Aligarh Historians Society / Tulika Books. p. 19. ISBN 978-81-85229-92-8.

- ↑ Paul J. Kosmin (2013). "Apologetic Ethnography: Megasthenes' Indica and the Seleucid Elephant". In Eran Almagor, Joseph Skinner (ed.). Ancient Ethnography: New Approaches. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781472537607.p.91

- ↑ Paul J. Kosmin 2013, p. 98-100.

- ↑ Paul J. Kosmin 2013, p. 103-104.

- ↑ Paul J. Kosmin 2013, p. 98.

- ↑ Romila Thapar (1990). A History of India. Penguin Books Limited. ISBN 978-0-14-194976-5.p.89

- ↑ Romila Thapar (1990). A History of India. Penguin Books Limited. ISBN 978-0-14-194976-5. p. 548.

- ↑ Romila Thapar 1990, pp. 89–90

- ↑ Romila Thapar 2012, p. 118.

- ↑ pp.31-32