Meroe

| Author:Laxman Burdak, IFS (R) |

Meroe (मेरोइ) is an ancient city on the east bank of the Nile about 6 km north-east of the Kabushiya station near Shendi, Sudan, approximately 200 km north-east of Khartoum.

Variants

- mɛroʊeɪ

- Meroitic

- Medewi

- Bedewi

- Ancient Greek: Μερόη, Meróē

- Meroë

- Arabic: مرواه Meruwah and مروى Meruwi;

Jat Gotras Namesake

- Meriya = Meroë (Pliny.vi.35, Pliny.vi.35, , Pliny.vi.38, Pliny.vi.39)

History

Near the site are a group of villages called Bagrawiyah. This city was the capital of the Kingdom of Kush for several centuries. The Kushitic Kingdom of Meroë gave its name to the Island of Meroë, which was the modern region of Butana, a region bounded by the Nile (from the Atbarah River to Khartoum), the Atbarah and the Blue Nile.

The city of Meroë was on the edge of Butana and there were two other Meroitic cities in Butana: Musawwarat es-Sufra and Naqa.[1][2] The first of these sites was given the name Meroë by the Persian king, Cambyses, in honor of his sister who was called by that name. The city had originally borne the ancient appellation Saba, named after the country's original founder.[3] The eponym Saba, or Seba, is named for one of the sons of Cush (see: Genesis 10:7). The presence of numerous Meroitic sites within the western Butana region and on the border of Butana proper is significant to the settlement of the core of the developed region. The orientation of these settlements exhibit the exercise of state power over subsistence production.[4]

The Kingdom of Kush which housed the city of Meroë represents one of a series of early states located within the middle Nile. It is one of the earliest and most impressive states found south of the Sahara. Looking at the specificity of the surrounding early states within the middle Nile, one's understanding of Meroë in combination with the historical developments of other historic states may be enhanced through looking at the development of power relation characteristics within other Nile Valley states.[5]

The site of the city of Meroë is marked by more than two hundred pyramids in three groups, of which many are in ruins. They have the distinctive size and proportions of Nubian pyramids.

Meroë was the south capital of the Napata/Meroitic Kingdom, that spanned the period c. 800 BCE – c. 350 CE.[6] According to partially deciphered Meroitic texts, the name of the city was Medewi or Bedewi. Excavations revealed evidence of important, high ranking Kushite burials, from the Napatan Period (c. 800 – c. 280 BCE) in the vicinity of the settlement called the Western cemetery. The culture of Meroë developed from the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Ancient Egypt, which originated in Kush. The importance of the town gradually increased from the beginning of the Meroitic Period, especially from the reign of Arakamani (c. 280 BCE) when the royal burial ground was transferred to Meroë from Napata (Gebel Barkal).

In the fifth century BCE, Greek historian Herodotus described it as "a great city...said to be the mother city of the other Ethiopians."[7][8] The city of Meroë was located along the middle Nile which is of much importance due to the annual flooding of the Nile river valley and the connection to many major river systems such as the Niger which aided with the production of pottery and iron characteristic to the Meroitic kingdom that allowed for the rise in power of its people.[9]

Rome's conquest of Egypt led to border skirmishes and incursions by Meroë beyond the Roman borders. In 23 BCE the Roman governor of Egypt, Publius Petronius, to end the Meroitic raids, invaded Nubia in response to a Nubian attack on southern Egypt, pillaging the north of the region and sacking Napata (22 BCE) before returning home. In retaliation, the Nubians crossed the lower border of Egypt and looted many statues (among other things) from the Egyptian towns near the first cataract of the Nile at Aswan. Roman forces later reclaimed many of the statues intact, and others were returned following the peace treaty signed in 22 BCE between Rome and Meroë under Augustus and Amanirenas, respectively. One looted head though, from a statue of the emperor Augustus, was buried under the steps of a temple. It is now kept in the British Museum[10]

The next recorded contact between Rome and Meroë was in the autumn of 61 CE. The Emperor Nero sent a party of Praetorian soldiers under the command of a tribune and two centurions into this country, who reached the city of Meroë where they were given an escort, then proceeded up the White Nile until they encountered the swamps of the Sudd. This marked the limit of Roman penetration into Africa.[11]

The period following Petronius' punitive expedition is marked by abundant trade finds at sites in Meroë. L. P. Kirwan provides a short list of finds from archeological sites in that country.[12] However, the kingdom of Meroë began to fade as a power by the 1st or 2nd century CE, sapped by the war with Roman Egypt and the decline of its traditional industries.[13]

Meroë is mentioned succinctly in the 1st century CE Periplus of the Erythraean Sea:

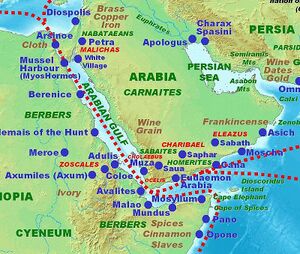

- 2. On the right-hand coast next below Berenice is the country of the Berbers. Along the shore are the Fish-Eaters, living in scattered caves in the narrow valleys. Farther inland are the Berbers, and beyond them the Wild-flesh-Eaters and Calf-Eaters, each tribe governed by its chief; and behind them, farther inland, in the country towards the west, there lies a city called Meroe....— Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, Chap.2

a stele of Ge'ez of an unnamed ruler of Aksum thought of as Ezana was found at the site of Meroë; from his description, in Greek, that he was "King of the Aksumites and the Omerites," (i.e. of Aksum and Himyar) it is likely this king ruled sometime around 330. While some authorities interpret these inscriptions as proof that the Axumites destroyed the kingdom of Meroe, others note that archeological evidence points to an economic and political decline in Meroe around 300.[14] Moreover, some view the stele as military aid from Aksum to Meroe to quell down the revolt and rebellion by the Nuba. However, conclusive evidence and proof to which view is correct is not currently present.

Mention by Pliny

Pliny[15] mentions Troglodytice....Juba states, too, that the inhabitants who dwell on the banks of the Nile from Syene as far as Meroë, are not a people of Æthiopia, but Arabians; and that the city of the Sun, which we have mentioned29 as situate not far from Memphis, in our description of Egypt, was founded by Arabians.

29 Heliopolis, described in B. v. c. 4.

Mention by Pliny

Pliny[16] mentions Ethiopia.... In a similar manner, also, there have been conflicting accounts as to the extent of this country: first by Dalion, who travelled a considerable distance beyond Meroë, and after him by Aristocreon and Basilis, as well as the younger Simonides, who made a stay of five years at Meroë13, when he wrote his account of Æthiopia. Timosthenes, however, the commander of the fleets of Philadelphus, without giving any other estimate as to the distance, says that Meroë is sixty days' journey from Syene; while Eratosthenes states that the distance is six hundred and twenty-five miles, and Artemidorus six hundred. Sebosus says that from the extreme point of Egypt, the distance to Meroë is sixteen hundred and seventy-five miles, while the other writers last mentioned make it twelve hundred and fifty.

All these differences, however, have since been settled; for the persons sent by Nero for the purposes of discovery have reported that the distance from Syene to Meroë is eight hundred and seventy-one miles, the following being the items.

13 See B. v. c. 10, where Meroë is also mentioned.

Meroë in Hebrew legend

Hebrew oral tradition avers that Moses, in his younger years, had led an Egyptian military expedition into Sudan (Kush), as far as the city of Meroë, which was then called Saba. The city was built near the confluence of two great rivers and was encircled by a formidable wall, and governed by a renegade king. To ensure the safety of his men who traversed that desert country, Moses had invented a stratagem whereby the Egyptian army would carry along with them baskets of sedge, each containing an ibis, only to be released when they approached the enemy's country. The purpose of the birds was to kill the deadly serpents that lay all about that country.[17] Having successfully laid siege to the city, the city was eventually subdued by the betrayal of the king's daughter, who had agreed to deliver the city to Moses on condition that he would consummate a marriage with her, under the solemn assurance of an oath.

External links

Se also

References

- ↑ "The Island of Meroe", UNESCO World Heritage". Whc.unesco.org.

- ↑ http://www.ancientsudan.org/meroe_gallery/index.htm

- ↑ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews (book 2, chapter 10, section 2) [Paragraph # 249]

- ↑ Edwards, David N. (1998). "Meroe and the Sudanic Kingdoms". The Journal of African History. 39 (2): 175–193. doi:10.1017/S0021853797007172. JSTOR 183595.

- ↑ Edwards, David N. (1998). "Meroe and the Sudanic Kingdoms". The Journal of African History. 39 (2): 175–193. doi:10.1017/S0021853797007172. JSTOR 183595.

- ↑ Török, László (1997). The Kingdom of Kush: Handbook of the Napatan-Meroitic Civilization. Handbuch der Orientalistik. Erste Abteilung, Nahe und der Mittlere Osten. Vol. 31. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 90-04-10448-8.

- ↑ Herodotus (1949). Herodotus. Translated by J. Enoch Powell. Translated by Enoch Powell. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 121–122.

- ↑ Connah, Graham (1987). African Civilizations: Precolonial Cities and States in Tropical Africa: An Archaeological Perspective. Cambridge University Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-521-26666-6.

- ↑ Edwards, David N. (1998). "Meroe and the Sudanic Kingdoms". The Journal of African History. 39 (2): 175–193. doi:10.1017/S0021853797007172. JSTOR 183595.

- ↑ ."Bronze head of Augustus". British Museum. 1999.

- ↑ Kirwan, L.P. (1957). "Rome beyond The Southern Egyptian Frontier". The Geographical Journal. London: Royal Geographical Society, with the Institute of British Geographers. 123 (1): 13–19. doi:10.2307/1790717. JSTOR 1790717.

- ↑ Kirwan, L. P. (1957). "Rome beyond The Southern Egyptian Frontier". The Geographical Journal. London: Royal Geographical Society, with the Institute of British Geographers

- ↑ "Nubia", BBC World Service". Bbc.co.uk.

- ↑ Munro-Hay, Stuart C. (1991). Aksum: An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 79, 224. ISBN 978-0-7486-0106-6.

- ↑ Natural History by Pliny Book VI/Chapter 34

- ↑ Natural History by Pliny Book VI/Chapter 35

- ↑ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, ii.x.ii.