Rataul Bagpat

| Author:Laxman Burdak, IFS (R) |

Rataul () is a village in Khekra tehsil in Baghpat District in Uttar Pradesh.

Location

Jat Gotras

History

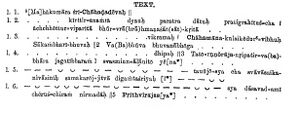

No. 26 Rataul Plate of Chahadadeva

[p,221]: The fragmentary copper-plate which is discussed in this note was acquired for the Director-General of Archaeology in 1911 by Mr. J. R. Pearson, I.C.S., District Officer of Meerut. The circumstances which led to its discovery were described in a forwarding note. It is stated that this inscribed fragment belonged to a copper-plate which was found, some thirty years ago, by a resident of the village of Rataul, Tahsil Baghpat, District Meerut, while he was excavating a piece of land belonging to him in order to dig out old bricks. The plate, which is said to have been imbedded in a domical structure nine or ton feet below the surface, was broken to pieces by the diggers and all the other fragments are said to have been lost. This is much to be regretted, for, as it will appear from the sequel, the inscription incised on the plate was of considerable interest.

The surviving fragment is deposited in the Museum of Archaeology at Delhi, and measures 10-1/2" in width at the top by 3-5/8" in height. It is complete only on the upper side, but a rough estimate of the total breadth of the fragment may be formed with the help of the missing portions of the verses that remain. It is impossible, however, to find out the entire height or the total number of lines as it is not known what portion of the plate is broken off at the bottom.

The extant portion of the document consists of parts of six lines. Of the seventh line the top bars of some letters and superscript vowel strokes of three syllables remain. The inscription is engraved in the Nagari characters of the beginning of the 13th century A.D. In respect of orthography we observe that the words have been spelt with accuracy throughout with the exception of the omission of the anusvara before dur in kulaikedur=, in line 3 and the substitution of śā for sā in -śātkrita in line 2. No distinction has been made between the letters v and b. It is noteworthy that the rules of sandhi have been nowhere disregarded. The doubling of chh in achchhettur (line 2) and of n in svasminn=ālānito (line 4), etc., show that the author and the scribe were well versed in grammar. The consonants before and after r have been doubled in some cases and left unaltered in others, in accordance with the optional character of the rule concerned. The avagraha is not indicated.

The language of the inscription, as far as it goes, is metrical Sanskrit with the exception of the first line. The remaining five lines contain portions of six verses which were numbered. The first verse, which is in the Arya metre, covers the entire extant portion of line 2. Of its

1. We must scan gaj-ety-. 2 Cf. Raghuvansha, VI,

[p.222]: first foot (pada) ten mātrās out of twelve survive, so that the loss on the left side is two mātrās or one long or two short syllables. It may also be assumed that the inscription opened with a short benedictory formula. The last foot of the verse wants four or seven matras according as the metre employed was Arya or Giti. The second verse terminates in line 3 and has lost the first thirteen syllables of the first half. This and the next two verses are in the Shloka metre. The fourth verse presumably ended in line 4. The next or fifth verse, which terminates in line 6, is in the Sardnlavikridita metre. The portions which remain include the last five syllables of the first foot, the whole of the second quarter and the last thirteen syllables of the last. Of the last verse the first five syllables only remain.

The object of the document was presumably to record a gift of land to one or more Brahmanas. This may be inferred, in the absence of the grant portion, from the first verse which affirms that the grantor and the grantee earn an everlasting bliss, whereas the land bestowed upon a Brahmana becomes a danger to him who appropriates it. That the donor was the chief heir-apparent, the illustrious Chahadadeva, whose name is engraved in large characters in the top line, needs no demonstration.1

The remainder of the inscription contains a part of the genealogy of Chahadadeva. Verses 2 and 3 eulogise a ruler whose name is missing. He is described as the ‘ sole moon of the Chahamana race ’ and the ‘ lord of the land of Shakambhari.’ Verse 4 records that after that ruler Arnnoraja 'bore the burden of the world.’ The first half of the fifth verse praises a son of Arnnoraja who is described as ‘ having focused in his own abode the prosperity of the quarters after he had conquered it.’ We meet with no other proper name until we come to verse 6, where we find the name of Prithviraja.

We proceed to fill up the gaps in the above account. The name between Arnnoraja and Prithviraja is readily ascertained from a short inscription on a pillar of an ancient building at Madanpur which records the conquest of Bundelkhand by Prithviraja, the son of Somesvara and grandson of Arnnoraja in Vikrama Samvat 1239 2. It is obvious that the Prithviraja of our inscription is the great Chahamana prince of Delhi and Ajmer. The name of Arnnoraja’s predecessor was Jaidev according to 'the transcript published by Kavi Raj Shyamal Das of Mewar of the important rock inscription at Bijholi.3 This transcript is faulty in many respects and it was, no doubt, for this reason that the late Prof. Kielborn preferred to publish an imperfect dynastic list of the Chahamanas in his Synchronistic table for Northern India.4 I understand that Mr. Bhandarkar is intending to re-edit the inscription. In the meantime we are fortunate in having another valuable record to refer to. I mean the important historical manuscript poem entitled the Prithiviraja-vijaya written by a Kashmir Pandit and now pre- served in the Deccan College at Poona. Mr. James Morison5 has proved the authenticity of this work both from internal evidence and from that of inscriptions.6 This poem, which contains a contemporary narrative of Prithiviraja’s career, begins with a complete genealogical account of his race. According to this, Arnnoraja’s father was Ajayaraja. We now see that what Kavi Raj Shyamal Das’s Pandit read as Jaidev in the Bijholi inscription must in reality be Ajayadeva.

We now come to Chahadadeva himself who issued the copper-plate. The last extant verse of our inscription begins with the genitive singular of ‘ Prithviraja,’ which might suggest that a son of this ruler was mentioned in this verse. This seems plausible in view of the fact that

1 In mediaeval grants the sign-manual of the granting ruler is often carved at the top or bottom of the document.

2 Archival. Surv. of India, Vol. X, p. 98, and Vol. XXI, pp. 173 f,

3 Journal Beng. As. Soc., Vol. LV, Part 1, p. 30.

4 Ep. Ind., Vol. VIII, Appendix I.

5 Vienna Oriental Journal, Vol. VII, pp. Ig8 ff.

6 Mr. Morison mentions only two inscriptions, namely, the Bijholi rock inscription and the Harsha stone inscription which supplies the names from Guvaka to Vigraharaja II. To these Gen. Cunningham added the Madanpur pillar inscription, Archaeological Survey of India, Report, Vol. X, Plate XXXII ; No. 10.

[p.223]: Hasan Nizami in his Taju-l-Maāsir states that Prithviraja had a very able son who, after his father’s execution, was appointed to the government of Ajmer.1 The Hammira-Mahakavya, which according to Kirtane contains a historic narrative from Prithviraja to Hammira, makes Hariraja the successor of Prithviraja at Ajmer, though it is not apparent how he was related to him.2 In the dynastic table extracted from the Prithiviraja-vijaya by Mr. Morison, Hariraja appears as the younger brother of Prithviraja. No son of the latter seems to be recorded in this poem.

We see from what has been said above that the surviving portion of the inscription supplies no clue as to the place of Chahadadeva in the Chahamana pedigree. Nor do the Sanskrit poems referred to in the preceding paragraph mention his name. It is true that in the genealogical tree of the Chahamana tribe published by Tod, Chahadadeva (spelt Chahirdeo) is shown as the younger brother of Prithviraja. But as Tod’s account of the Chahamanas is based on the Prithviraja Rasa which has been proved to be a forgery,3 we cannot accept this information as correct unless it is supported by some more reliable source. For the present, the question must remain an open one. There is one thing, however, about this prince which seems to be fairly certain, namely, that he is in all probability the same as the ruler of that name who flourished at Narwar (ancient Nalapura) in Gwalior State in the first half of the 13th century A.D. We shall examine the evidence in the following paragraphs.

General Cunningham has shown from an inscription discovered by him in the ancient fort of Narwar that the rulers of that place included a line of five chiefs the last of whom, Ganapati, was reigning in 1298 A.D. (Vikrama Samvat 1355).4

The genealogy of this family opens with Chahadadeva, whose coins bear dates Vikrama Samvat 1295 to 1311 (A.D. 1255).5 There is, however, an earlier ruler named Malayavarmadeva whose name figures in numismatic works under the Narwar family. His coins bear dates Samvat 1280, 1283 and 1290 and have been found at Narwar, Gwalior and Jhansi. General Cunningham was of opinion that Malayavarmadeva was a ruler of Narwar but that he belonged to a different dynasty and was ejected from Narwar by Chahadadeva who 'was consequently the founder of the above mentioned family of Narwar.6

Now, as the Chahamana Chahadadeva of the inscription under review flourished just about this time, if we are to judge from the type of characters used in it, I am inclined to think that the founder of the Narwar family was no other than his namesake of the Chahamana tribe. When precisely Chahadadeva or his family migrated to Narwar, cannot yet be determined. It may have happened after the downfall of Prithviraja when his followers escaped from Delhi and Ajmer in large numbers. The Muhammadan historians tell us very little about this period. But we learn from the Hammira-Mahakavya that not long after the defeat of Prithviraja the Chahamanas were turned out of Ajmer, when they retired to Ranathambhor, which continued in their possession until Hammira-deva was slain and the town captured by Alau-ddin in 1299 A.D.7 It is surprising that the Hammira-Mahakavya, as it exists,8 does not

1 Elliott, History of India, Vol. II, p. 216. According to Tod (Rajasthan, II, p. 451) Prithviraja had a son by name Rainsi who was slain in the battle with Shahabu-d-din.

2 Ind. Ant., Vol. VIII, pp. 61-62. Rajasthan, II, p. 451.

3 Journal of Beng. As. Soc., Vol. LV, Part I, pp. 5 ff.

4 Archeological Survey of India, Reports, Vol. II, p. 315, and Ind. Ant., Vol. XXII, p. 81.

5 Cunningham, Coins of Medieval India, pp. 92-93 and PI. X.

6 Later, Cunningham changed his opinion and declared that Malaya may have belonged to the same family. The latter view seems to me to be unlikely.

7 This last event is narrated by Muhammadan historians in detail. Cf. Tarikh-i-Firoz Shahi in Elliott History of India, Vol. III, pp. 171-179. ’ 8 Mr. Kirtane made his analysis from a copy which is dated in Vikrama Samvat 1542, ie., 186 years after the death of Hammira.

[p.224]: mention the name of Chahadadeva among the chiefs of Ranathambhor. This, however, is not a serious objection. For we learn from a Muhammadan historian, named Maulana Minhaju-ddin, that in A.H. 632 (A.D. 1234) Shamsu-d-din Altamsh defeated at Ranathambhor a powerful ruler of the name of Chahadadeva who sustained another defeat in A. H. 649 (A.D. 1251) near Narwar at the hands of Ulugh Khan, the Commander of the forces of Balban.1 This account must be correct, for Minhaju-d-din informs us that he heard of Chahadadeva’s bravery at the battle of Ranathambhor from the mouth of Nusratu-d-din Ta-yas‘ai himself who led Altamash’s forces on this occasion.3 We may, therefore, conclude that Chahadadeva held sway over both Ranathambhor and Narwar where, indeed, he is said to have been born.3 This need not surprise us for we learn from the Delhi-Siwalik pillar inscription that at one time the Chahamanas ruled over the entire territory between the Himalayas and the Vindhyas. It also follows from what has been said above that Chahadadeva must have flourished just mid-way between the fall of Prithviraja and that of Hammira.

Another argument in favour of the identification of the Chahamana Chahadadeva of our inscription and the Chahadadeva of Narwar is afforded by numismatic records. The coins of Chahadadeva discovered at Narwar, etc. are of two kinds, namely those issued by him as an independent ruler and secondly those struck by him as a tributary to Altamsh. The coins of both these kinds are of the bull and horseman type like those of the Chahamana rulers and, what is more, those of the first kind also hear on the reverse the legend of Asavari-sri-Samantadeva4 which only occurs on the coins of the Chahamana Somesvara and his son Prithviraja.

It will be observed that in the inscription, Chahadadeva is called a Mahakumara or chief heir-apparent. The grant must consequently have been issued by him before his enthronement.

1 Cunningham (Coins of Medieval India, pp. 90-91) and Thomas (Pathans of Delhi, p. 67) maintained that one and the same Hindu chief was defeated at Ranathambhor and Narwar. According to Cunningham Major Raverty held that two different rulers were intended. This view is refuted by Major Raverty’s own translation of the Tabakat-i-Nasiri (p. 824) where both the defeats are clearly attributed to the same person.

2 Tabakat-i-Nasiri translated by Raverty, p. 825.

3 Ind. Ant, Vol. XXII, p. 81.

4 This legend is evidently developed from that of Sri-Samantadeva on the Tomara coins, which is perfectly natural, for the Chahamanas were the immediate successors of the Tomaras at Delhi. (See Palam Baoli inscription in Journal Beng. As. Soc., Vol. XLI1I, Part I, Pi. X.) inscription

5 A part of the top stroke of ma is extant. 6 Read - Kemdurs.

Population

Notable persons

External Links

References

Back to Jat Villages