Stenness

Stenness is a village and parish on the Orkney Mainland in Scotland.[1] Between Harry Loch and the Stennes Loch stand two monuments - the notable prehistoric monuments the Standing Stones of Stenness and the Ring of Brodgar. Close by is Maes Howe, a stunning stone-built tomb chamber and a prehistoric village found in 1980 nearby Barnhause. [2]

Geography

Stenness parish adjoins the southern extremity of the Loch of Stenness,[3] and also some notable standing stones. It is bounded on the west by the efflux of the loch, and a branch of Hoy Sound, and has been politically merged with Firth.[4]

History

In Old Norse: Steinnes[5] or Steinsnes[6] means headland/peninsula of the stone.

The area has been inhabited for a considerable time. Near the village are several notable prehistoric monuments including the Stones of Stenness and the Ring of Brodgar.[7]

The sole entrance to the circle at Stenness faces the site of the ancient village at Barnhouse while around it stand other sentinel stones. The watch stone is the largest and it guards the causeway leading to the Ness of Brodgar and Ring of Brodgar. [8]

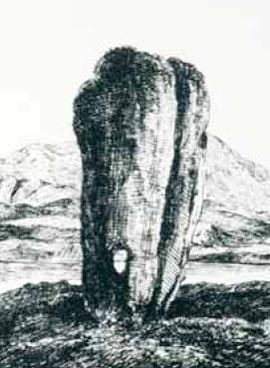

Odin-Stone: Traditions and history

- Let us imagine, then, families approaching Stenness at the appointed time of year, men, women and children, carrying bundles of bones collected together from the skeletons of disinterred corpses–skulls, mandibles, long bones–carrying also the skulls of totem animals, herding a beast that was one of several to be slaughtered for the feasting that would accompany the ceremonies..... — Aubrey Burl, Rites of the Gods, 1981.[9]

Even in the 18th century the site was still associated with traditions and rituals, by then relating to Norse gods. It was visited by Walter Scott in 1814. Other antiquarians documented the stones and recorded local traditions and beliefs about them. One stone, known as the "Odin Stone" which stood in the field to the north of the henge,[10] was pierced with a circular hole, and was used by local couples for plighting engagements by holding hands through the gap. It was also associated with other ceremonies and believed to have magical power.[11] There was a reported tradition of making all kinds of oaths or promises with one's hand in the Odin Stone; this was known as taking the "Vow of Odin".[12]

In December 1814 Captain W. Mackay, a recent immigrant to Orkney who owned farmland in the vicinity of the stones, decided to remove them on the grounds that local people were trespassing and disturbing his land by using the stones in rituals. He started in December 1814 by smashing the Odin Stone. This caused outrage and he was stopped after destroying one other stone and toppling another.[13]

The toppled stone was re-erected in 1906 along with some inaccurate reconstruction inside the circle.[14]

In the 1970s, a dolmen structure was toppled, since there were doubts as to its authenticity. The two upright stones remain in place.[15]

A picture of the Stones of Stenness features on the cover of Van Morrison's album The Philosopher's Stone, and the Odin stone is depicted on Julian Cope's album Discover Odin.

World Heritage status

"The Heart of Neolithic Orkney" was inscribed as a World Heritage site in December 1999. In addition to Skara Brae the site includes Maeshowe, the Ring of Brodgar, the Standing Stones of Stenness and other nearby sites. It is managed by Historic Scotland, whose "Statement of Significance" for the site begins:

- The monuments at the heart of Neolithic Orkney and Skara Brae proclaim the triumphs of the human spirit in early ages and isolated places. They were approximately contemporary with the mastabas of the archaic period of Egypt (first and second dynasties), the brick temples of Sumeria, and the first cities of the Harappa culture in India, and a century or two earlier than the Golden Age of China. Unusually fine for their early date, and with a remarkably rich survival of evidence, these sites stand as a visible symbol of the achievements of early peoples away from the traditional centres of civilisation.[16]

See also

- Gurg (गुर्ग) is an ancient historical place in Adilabad district of Telangana, India. It is known for prehistoric monuments of stone circles similar to those in Stonehenge in Britain. [17]

External links

References

- ↑ United Kingdom Ordnance Survey Map Landranger 45, Orkney Mainland, 1:50,000 scale, 2003

- ↑ Alistair Moffat: The British: A Genetic Journey, Birlinn, 2013, ISBN:9781780270753, p.72

- ↑ Wilson, Rev. John (1882). "The Gazetteer of Scotland". Edinburgh: W. & A.K. Johnstone.

- ↑ Wilson, Rev. John (1882). "The Gazetteer of Scotland". Edinburgh: W. & A.K. Johnstone.

- ↑ Pedersen, Roy (January 1992) Orkneyjar ok Katanes (map, Inverness, Nevis Print)

- ↑ Anderson, Joseph (Ed.) (1893) Orkneyinga Saga. Translated by Jón A. Hjaltalin & Gilbert Goudie. Edinburgh. James Thin and Mercat Press (1990 reprint). ISBN 0-901824-25-9

- ↑ Paola Arosio & Diego Meozzi. "Stones of Stenness". Stone Pages. Retrieved 2009-07-25.

- ↑ Alistair Moffat: The British: A Genetic Journey, Birlinn, 2013, ISBN:9781780270753, p.75

- ↑ Orkneyjar – The Odin Stone

- ↑ Wickham-Jones, Caroline (2012). Monuments of Orkney. Historic Scotland. ISBN 978-1-84917-073-4.

- ↑ Orkneyjar – The Odin Stone

- ↑ Wade, Z. E. A. (1895). Pixy-led in North Devon: Old Facts and New Fancies. Devon: Marshall Bros. p. 223.

- ↑ Alistair Moffat: The British: A Genetic Journey, Birlinn, 2013, ISBN:9781780270753,p.75

- ↑ Orkneyjar - The Standing Stones of Stenness

- ↑ "Stones Of Stenness Circle And Henge". Historic Scotland.

- ↑ "The Heart of Neolithic Orkney". Historic Scotland. Archived from the original on 11 September 2007.

- ↑ Aitihasik Sthanavali by Vijayendra Kumar Mathur, p.292