Swedes

| Author:Laxman Burdak, IFS (R) |

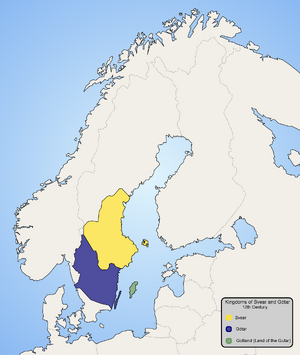

| Distribution of Geats |

| Distribution of Swedes |

| Distribution of Gutes |

Swedes (Swedish: svenskar) are a North Germanic ethnic group native to the Nordic region, primarily their nation state of Sweden,[1] who share a common ancestry, culture, history and language. They mostly inhabit Sweden and the other Nordic countries, in particular Finland where they are an officially recognized minority, with a substantial diaspora in other countries, especially the United States.

Variants

- Swede

- Svensk

- Svenskar

- Suiones (by Tacitus)

- Suetides

- Svear

- Svea

- Suehans

- Suones

- Sueones

- Sweones

- Swiones

- Sviones

Jat clans

Etymology

The English term "Swede" has been attested in English since the late 16th century and is of Middle Dutch or Middle Low German origin.[2] In Swedish, the term is svensk, which is from the name of svear (or Swedes), the people who inhabited Svealand in eastern central Sweden,[3] and were listed as Suiones in Tacitus' history Germania from the first century AD. The term Swedes is believed to have been derived from the Proto-Indo-European reflexive pronominal root, *s(w)e, as the Latin suus. The word must have meant "one's own (tribesmen)". The same root and original meaning is found in the ethnonym of the Germanic tribe Suebi, preserved to this day in the name Swabia.[4]

History

Origins: Like other Scandinavians, Swedes descend from the presumably Indo-European Battle Axe culture and also the Pitted Ware culture.[5] Prior to the first century AD there is no written evidence and historiography is based solely on various forms of archeology. The Proto-Germanic language is thought to have originated in the arrival of the Battle Axe culture in Scandinavia[6] and the Germanic tribal societies of Scandinavia were thereafter surprisingly stable for thousands of years.[7] The merger of the Battle Axe and Pitted Ware cultures eventually gave rise to the Nordic Bronze Age which was followed by the Pre-Roman Iron Age. Like other North Germanic peoples, Swedes likely emerged as a distinct ethnic group during this time.[8]

Swedes enters written proto-history with the Germania of Tacitus in 98 AD. In Germania 44, 45 he mentions the Swedes (Suiones) as a powerful tribe (distinguished not merely for their arms and men, but for their powerful fleets) with ships that had a prow in both ends (longships). Which kings (kuningaz) ruled these Suiones is unknown, but Norse mythology presents a long line of legendary and semi-legendary kings going back to the last centuries BC. As for literacy in Sweden itself, the runic script was in use among the south Scandinavian elite by at least the second century AD, but all that has survived from the Roman Period is curt inscriptions on artefacts, mainly of male names, demonstrating that the people of south Scandinavia spoke Proto-Norse at the time, a language ancestral to Swedish and other North Germanic languages.

Migration Age and Vendel Period

The migration age in Sweden is marked by the extreme weather events of 535–536 which is believed to have shaken Scandinavian society to its core. As much as 50% of the population of Scandinavia is thought to have died as a result and the emerging Vendel Period shows an increased militarization of society.[9][10] Several areas with rich burial gifts have been found, including well-preserved boat inhumation graves at Vendel and Valsgärde, and tumuli at Gamla Uppsala. These were used for several generations. Some of the riches were probably acquired through the control of mining districts and the production of iron. The rulers had troops of mounted elite warriors with costly armour. Graves of mounted warriors have been found with stirrups and saddle ornaments of birds of prey in gilded bronze with encrusted garnets. The Sutton Hoo helmet very similar to helmets in Gamla Uppsala, Vendel and Valsgärde shows that the Anglo-Saxon elite had extensive contacts with Swedish elite.[11]

In the sixth century Jordanes named two tribes, which he calls the Suehans and the Suetidi, who lived in Scandza. The Suehans, he says, have very fine horses just as the Thyringi tribe (alia vero gens ibi moratur Suehans, quae velud Thyringi equis utuntur eximiis). The Icelander Snorri Sturluson (1179–1241) wrote of the sixth-century Swedish king Adils (Eadgils) that he had the finest horses of his days. The Suehans supplied black fox-skins for the Roman market. Then Jordanes names the Suetidi which is considered to be the Latin form of Svitjod. He writes that the Suetidi are the tallest of men—together with the Dani, who were of the same stock. Later he mentions other Scandinavian tribes as being of the same height.

Originating in semi-legendary Scandza (believed to be somewhere in modern Götaland, Sweden), a Gothic population had crossed the Baltic Sea before the second century AD. They reaching Scythia on the coast of the Black Sea in modern Ukraine, where Goths left their archaeological traces in the Chernyakhov culture. In the fifth and sixth centuries, they became divided as the Visigoths and the Ostrogoths, and established powerful successor-states of the Roman Empire in the Iberian peninsula and Italy respectively.[12] Crimean Gothic communities appear to have survived intact in the Crimea until the late-18th century.[13]

Viking and Middle Ages

The Swedish Viking Age lasted roughly between the eighth and 11th centuries. During this period, it is believed that the Swedes expanded from eastern Sweden and incorporated the Geats to the south.[14] It is believed that Swedish Vikings and Gutar mainly travelled east and south, going to Finland, the Baltic countries, Russia, Belarus, Ukraine the Black Sea and further as far as Baghdad. Their routes passed through the Dnieper down south to Constantinople, on which they did numerous raids. The Byzantine Emperor Theophilos noticed their great skills in war and invited them to serve as his personal bodyguard, known as the varangian guard. The Swedish Vikings, called "Rus" are also believed to be the founding fathers of Kievan Rus. The Arabic traveller Ibn Fadlan described these Vikings as following:

- I have seen the Rus as they came on their merchant journeys and encamped by the Itil. I have never seen more perfect physical specimens, tall as date palms, blond and ruddy; they wear neither tunics nor caftans, but the men wear a garment which covers one side of the body and leaves a hand free. Each man has an axe, a sword, and a knife, and keeps each by him at all times. The swords are broad and grooved, of Frankish sort. — [15]

The adventures of these Swedish Vikings are commemorated on many runestones in Sweden, such as the Greece Runestones and the Varangian Runestones. There was also considerable participation in expeditions westwards, which are commemorated on stones such as the England Runestones. The last major Swedish Viking expedition appears to have been the ill-fated expedition of Ingvar the Far-Travelled to Serkland, the region south-east of the Caspian Sea. Its members are commemorated on the Ingvar Runestones, none of which mentions any survivor. What happened to the crew is unknown, but it is believed that they died of sickness.

Kingdom of Sweden

It is not known when and how the 'kingdom of Sweden' was born, but the list of Swedish monarchs is drawn from the first kings who ruled both Svealand (Sweden) and Götaland (Gothia) as one province with Erik the Victorious. Sweden and Gothia were two separate nations long before that into antiquity. It is not known how long they existed, but Beowulf described semi-legendary Swedish-Geatish wars in the sixth century.

Cultural advances

During the early stages of the Scandinavian Viking Age, Ystad in Scania and Paviken on Gotland, in present-day Sweden, were flourishing trade centres. Remains of what is believed to have been a large market have been found in Ystad dating from 600 to 700 AD.[16] In Paviken, an important centre of trade in the Baltic region during the ninth and tenth centuries, remains have been found of a large Viking Age harbour with shipbuilding yards and handicraft industries. Between 800 and 1000, trade brought an abundance of silver to Gotland, and according to some scholars, the Gotlanders of this era hoarded more silver than the rest of the population of Scandinavia combined.[17]

St. Ansgar is usually credited for introducing Christianity in 829, but the new religion did not begin to fully replace paganism until the 12th century. During the 11th century, Christianity became the most prevalent religion, and from 1050 Sweden is counted as a Christian nation. The period between 1100 and 1400 was characterized by internal power struggles and competition among the Nordic kingdoms. Swedish kings also began to expand the Swedish-controlled territory in Finland, creating conflicts with the Rus who no longer had any connection with Sweden.[18]

Feudal institutions in Sweden

Except for the province of Skane, on the southernmost tip of Sweden which was under Danish control during this time, feudalism never developed in Sweden as it did in the rest of Europe.[19] Therefore, the peasantry remained largely a class of free farmers throughout most of Swedish history. Slavery (also called thralldom) was not common in Sweden,[20] and what slavery there was tended to be driven out of existence by the spread of Christianity, the difficulty in obtaining slaves from the lands east of the Baltic Sea, and by the development of cities before the 16th century[21] Indeed, both slavery and serfdom were abolished altogether by a decree of King Magnus Erickson in 1335. Former slaves tended to be absorbed into the peasantry and some became laborers in the towns. Still, Sweden remained a poor and economically backward country in which barter was the means of exchange. For instance, the farmers of the province of Dalsland would transport their butter to the mining districts of Sweden and exchange it there for iron, which they would then take down to the coast and trade the iron for fish they needed for food while the iron would be shipped abroad.[22]

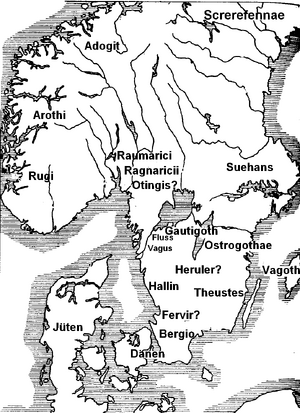

Inhabitants of Scandza

Jordanes names a multitude of tribes living in Scandza, which he named a womb of nations (loosely translated), and says they were taller and more ferocious than the Germans (archaeological evidence has shown the Scandinavians of the time were tall, probably due to their diet). This is a strong evidence that they were Jats. The listing represents several instances of the same people named twice, which was probably due to the gathering of information from diverse travellers[23] and from Scandinavians arriving to join the Goths, such as Rodwulf from Bohuslän.[24] Whereas linguists have been able to connect some names to regions in Scandinavia, there are others that may be based on misunderstandings.[25]

On the island there were the Screrefennae (i.e. Sami peoples[26]) who lived as hunter-gatherers living on a multitude of game in the swamps and on birds' eggs.

There were also the Suehans (Swedes) who had splendid horses like the Thuringians (Snorri Sturluson wrote that the 6th-century Swedish king Adils had the best horses of his time). They were the suppliers of black fox skins for the Roman market and they were richly dressed even though they lived in poverty.

There were also the Theustes (the people of the Tjust region in Småland), Vagoths (probably the Gutes of Gotland[27]), Bergio (either the people of Bjäre Hundred in Skåne, according to L Weibull, or the people of Kolmården according to others), Hallin (southern Halland) and the Liothida (either the Luggude Hundred or Lödde in Skåne, but others connect them to Södermanland[28]) who live in a flat and fertile region, due to which they are subject to the attacks of their neighbours.

Other tribes were the Ahelmil (identified with the region of Halmstad[29]), the Finnaithae (Finnhaith-, i.e. Finnheden, the old name for Finnveden), the Fervir (the inhabitants of Fjäre Hundred) and the Gautigoths (the Geats of Västergötland), a nation which was bold and quick to engage in war.

There were also the Mixi, Evagreotingis (or the Evagres and the Otingis depending on the translator), who live like animals among the rocks (probably the numerous hillforts and Evagreotingis is believed to have meant the "people of the island hill forts" which best fits the people of southern Bohuslän[30]).

Beyond them, there were the Ostrogoths (Östergötland), Raumarici (Romerike), the Ragnaricii (probably Ranrike, an old name for the northern part of Bohuslän) and the most gentle Finns (probably the second mention of the Sami peoples[31] mixed for no reason). The Vinoviloth (possibly remaining Lombards, vinili[32]) were similar.

He also named the Suetidi; a second mention of the Swedes[33][34] It can also be relevant to discuss if the term "Suetidi" could be equated with the term "Svitjod".[35] The Dani were of the same stock and drove the Heruls from their lands. Those tribes were the tallest of men.

In the same area there were the Granni (Grenland[36]), Augandzi (Agder[37]), Eunixi, Taetel, Rugii ([38]), Arochi ([39]) and Ranii (possibly the people of Romsdalen[40]). The king Rodulf was of the Ranii but left his kingdom and joined Theodoric, king of the Goths.

External links

References

- ↑ Minahan, James (2000). One Europe, many nations: a historical dictionary of European national groups. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 769. ISBN 0313309841. "Germanic nations:.. Swedes..."

- ↑ "the definition of Swede". Dictionary.com.

- ↑ "OSA – Om svar anhålles". g3.spraakdata.gu.se.

- ↑ Noreen, A. Nordens äldsta folk- och ortnamn (i Fornvännen 1920 sid 32).

- ↑ Malmström, Helena (19 January 2015). "Ancient mitochondrial DNA from the northern fringe of the Neolithic farming expansion in Europe sheds light on the dispersion process". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. Royal Society. 370 (1660): 20130373. doi:10.1098/rstb.2013.0373. PMC 4275881. PMID 25487325.

- ↑ Aubin, Hermann. "History of Europe: Barbarian migrations and invasions The Germans and Huns". Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ↑ Waldman, Carl; Mason, Catherine (2006). pp. 830–831. Encyclopedia of European Peoples. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1438129181.

- ↑ Sørensen, Marie Louise Stig. "History of Europe: The Bronze Age". Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ↑ Ström, Folke: Nordisk Hedendom, Studentlitteratur, Lund 2005, ISBN 91-44-00551-2 (first published 1961) among others, refer to the climate change theory.

- ↑ Eriksson, Benny (9 May 2016). "Mytisk extremvinter visade sig stämma". SVT.

- ↑ Bruce-Mitford, Rupert (1974). Aspects of Anglo-Saxon Archaeology: Sutton Hoo and Other Discoveries. London: Victor Gollancz

- ↑ Goth (people). Britannica Online Encyclopedia.

- ↑ Ingemar Nordgren (2004). "The Well Spring of the Goths: About the Gothic Peoples in the Nordic Countries and on the Continent". iUniverse. p. 520 ISBN 0-595-33648-5

- ↑ "Sweden". The Columbia Encyclopedia (Sixth ed.). bartleby.com. 2000.

- ↑ Quoted from: Gwyn Jones. A History of the Vikings. Oxford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-19-280134-1. Page 164.

- ↑ Sawyer, Birgit and Peter Sawyer (1993). Medieval Scandinavia: from Conversion to Reformation, Circa 800–1500. University of Minnesota Press, 1993. ISBN 0-8166-1739-2, pp. 150–153.

- ↑ Sawyer, Birgit and Peter Sawyer (1993). Medieval Scandinavia: from Conversion to Reformation, Circa 800–1500. University of Minnesota Press, 1993. ISBN 0-8166-1739-2, pp. 150–153.

- ↑ Bagge, Sverre (2005) "The Scandinavian Kingdoms". In The New Cambridge Medieval History. Eds. Rosamond McKitterick et al. Cambridge University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-521-36289-X, p. 724: "Swedish expansion in Finland led to conflicts with Rus', which were temporarily brought to an end by a peace treaty in 1323, dividing the Karelian peninsula and the northern areas between the two countries."

- ↑ Franklin D. Scott, Sweden: The Nation's History (University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, 1977) p. 58.

- ↑ Träldom. Nordisk familjebok / Uggleupplagan. 30. Tromsdalstind – Urakami /159–160, 1920. (In Swedish)

- ↑ Scott, p. 55.

- ↑ Scott, pp. 55–56.

- ↑ Nerman, B. Det svenska rikets uppkomst. Stockholm, 1925. p.46

- ↑ Ohlmarks, Å. (1994). Fornnordiskt lexikon, p.255

- ↑ Burenhult 1996:94

- ↑ Nerman 1925:36

- ↑ Nerman 1925:40

- ↑ Nerman 1925:38

- ↑ Ohlmarks 1994:10

- ↑ Nerman 1925:42ff

- ↑ Nerman 1925:44

- ↑ See Christie, Neil. The Lombards: The Ancient Longobards (The Peoples of Europe Series). ISBN 978-0-631-21197-6.

- ↑ Nerman 1925:44

- ↑ Thunberg, Carl L. (2012). Att tolka Svitjod. University of Gothenburg/CLTS. p. 44. ISBN 978-91-981859-4-2.

- ↑ Thunberg 2012:44-52.

- ↑ Nerman 1925:45

- ↑ Nerman 1925:45

- ↑ RogalandNerman 1925:45

- ↑ HordalandNerman 1925:45

- ↑ Nerman 1925:45

Back to Variants of Jat