Zaranj

| Author:Laxman Burdak, IFS (Retd.) |

Zaranj (Hindi:जरंज, Persian/Pashto/Balochi: زرنج) is a city in southwestern Afghanistan, near the border with Iran. It is the capital of Nimruz province. Drangiana or Zarangiana (Greek: Δραγγιανή) also attested in Old Western Iranian as Zranka.[1]

Variants of name

- Dranga (द्रंग) - Kingdom mentioned in Rajatarangini - Book VIII (i) (p.136, 178); Book VIII (ii) (p.245, 255)

- Drangiana (Greek)

- Dzaranda (Pashto)

- Jarang

- Jaranj

- Zarang (जरंग)

- Zarangia

- Zaranka (Old Persian)

- Zarani

- Zaranj (जरंज)

- Zarin

- Zirra

- Zranka (Old Persian)

Location

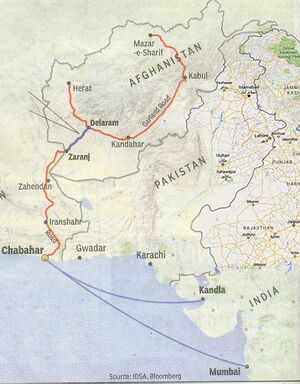

It is linked by highways with Lashkar Gah to the east, Farah to the north and the Iranian city of Zabol to the west. Zaranj serves as the border crossing between Afghanistan and Iran, which is of significant importance to the trade-route between Central Asia and South Asia with the Middle East. Zaranj is a Trading and Transit Hub in western Afghanistan, on the border with Iran.

Jat clans

History

Drangiana: Modern Zaranj bears the name of an ancient city whose name is also attested in Old Persian as Zranka. In Greek, this word became Drangiana.

In ancient times Drangiana was inhabited by an Iranian tribe which the ancient Greeks called Sarangians or Drangians. Drangiana was possibly subdued by another Iranian people, the Medes, and later, certainly, by the expanding Persian Empire of Cyrus the Great (559-530 BC).[2]

According to Herodotus, during the reign of Darius I (522-486 BC), the Drangians were placed in the same district as the Utians, Thamanaeans, Mycians, Drangians, and those deported to the Persian Gulf.

The capital of Drangiana, called Zarin or Zranka (like the Province), is identified with great probability with the extensive Achaemenid site of Dahan-e Gholaman southeast of Zabol in Iran.[3] Another significant center was the city of Prophthasia, possibly located at modern Farah in Afghanistan.[4] On occasion Drangiana was governed by the same satrap as neighboring Arachosia. In 330-329 BC, the region was conquered by Alexander the Great.[5] Drangiana continued to constitute an administrative district under Alexander and his successors. At Alexander's death in 323 BC, it was governed by Stasanor of Soloi, and later, in 321 BC, it was allotted to another Cypriot, Stasandros. By the end of the 4th century BC, Drangiana was part of the Seleucid Empire, but in the second half of the 3rd century BC it was at least temporarily annexed by Euthydemos I of Bactria. In 206-205 BC Antiochos III (222-187 BC) seems to have recovered Drangiana for the Seleucids during his Anabasis. The history of Drangiana during the weakening of Seleucid rule is unclear, but by the mid-2nd century BC the area was conquered by the expanding Parthian Empire of the Arsacids.[6]

Other historical names for Zaranj include Zirra,[7] Zarangia, Zarani etc.[8]

Ultimately the word Zaranj is derived from the ancient Old Persian word zaranka ("waterland"; cf. Pashto dzaranda). The region of Drangiana where the Helmand or the Hindmand meets Hamun-e-helmand and creates a fertile inland delta was known in Sassanid times as 'kuchak-e-hind' or 'little India'.

Achaemenid Zranka, the capital of Drangiana, was almost certainly located at Dahan-e Gholaman, southeast of Zabol in Iran.[9]

After the abandonment of that city, its name, Zarang or Zaranj in later Perso-Arabic orthography, was transferred to the subsequent administrative centers of the region, which itself came to be known as Sakastān, then Sijistan and finally Sistān.

Medieval Zaranj is located at Nād-i `Alī, 4.4 km north of the modern city of Zaranj.[10] According to the Arab geographers, prior to medieval Zaranj, the capital of Sistan was located at Ram Shahristan (Abrashariyar). Ram Shahristan had been supplied with water by a canal from the Helmand River, but its dam broke, the area was deprived of water, and the populace moved three days' march to found Zaranj.[11]

The area came under Muslim rule in 652, when Zaranj surrendered to the governor of Khurāsān; it subsequently became a base for further caliphal expansion in the region.

In 661, a small Arab garrison reestablished its authority in the region after having temporarily lost control due to skirmishes and revolts.[12]

A Nestorian Christian community is recorded in Zaranj in the sixth century, and by the end of the eighth century there was a Jacobite diocese of Zaranj.[13]

In the 9th century Zaranj was the capital of the Saffarid dynasty, whose founder was the local coppersmith turned warlord, Ya'qub ibn al-Layth al-Saffar.[14]

It became part of the Ghaznavids, Ghorids, Trimurids, Safavids and others. Defeated by the Samanids in 900, the Saffarids sank to a position of regional importance, until conquered by Mahmud of Ghazni in 1003.[15]

Subsequently Zaranj served as the capital of the Nasrid (1029-1225) and Mihrabānid (1236-1537) maliks of Nīmrūz.[16]

In the early 18th century, the city became part of the Afghan Hotaki dynasty until they were removed from power in 1738 by Nader Shah of Khorasan.

By 1747, Ahmad Shah Durrani made it part of modern Afghanistan after he united all the different tribes and acquired the territories from northeastern Iran to Delhi in India. Under the modern Afghan governments, the area was known as Farah-Chakansur Province until 1968, when it was separated to form the provinces of Nimruz and Farah.[17] The city of Zaranj became the capital of Nimroz.

Recent Road Construction

A new highway called Route 606 was built between Zaranj and Delaram in Farah province by the Indian Government's Border Roads Organization at a cost of about US $136 million to open up a link between the deep sea port at Chabahar in Iran to Afghanistan's main ring road highway system which connects Kabul, Kandahar, Herat, Mazar-i-Sharif and Kunduz. The 215-km long highway, a symbol of India's developmental work in the war-ravaged country, was handed over to Afghan authorities by Indian External Affairs Minister Pranab Mukherjee in January 2009 in the presence of Afghan President Hamid Karzai and Foreign Minister Rangeen Dadfar Spanta.

External links

References

- ↑ Schmitt, Rüdiger (15 December 1995). "DRANGIANA or Zarangiana; territory around Lake Hāmūn and the Helmand river in modern Sīstān". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- ↑ Schmitt (1995)

- ↑ G. Gnoli, "Dahan-e Ḡolāmān," Encyclopaedia Iranica, vol. 6 (1993) 582-585.

- ↑ Schmitt (1995)

- ↑ Schmitt (1995)

- ↑ Schmitt (1995)

- ↑ Ten Thousand Miles in Persia: Or, Eight Years in Irán By Percy Sykes, pg. 363

- ↑ Vogelsang, Willem (2002). The Afghans. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 162. ISBN 0-631-19841-5. Retrieved 2011-01-21.

- ↑ Gnoli (1993).

- ↑ Schmitt (1995).

- ↑ Guy Le Strange. The lands of the eastern caliphate: Mesopotamia, Persia, and Central Asia, from the Moslem conquest to the time of Timur. Cambridge geographical series. General editor: F. H. H. Guillemard. reprint Publisher CUP Archive, 1930. Originally published 1905.

- ↑ Islamic History: A New Interpretation By Muhammad Abdulhavy Shaban

- ↑ Fiey, Pour un Oriens Christianus, 281

- ↑ Ariana Antiqua: A Descriptive Account of the Antiquities and Coins of Afghanistan By Horace Hayman Wilson, pg. 154

- ↑ Joel L. Kraemer, Philosophy in the Renaissance of Islam: Abū Sulaymān Al-Sijistānī and His Circle, Vol. VIII, ed. Itamar Rabinovich, William M. Brinner, Martin Kramer, Joel L. Kraemer and Shimon Shamir, (Brill, 1986), 4.

- ↑ Zaranj, C.E. Bosworth, The Encyclopaedia of Islam, ed. P. J. Bearman, T. Bianquis, C. E. Bosworth, E. Van Donzel and W. P. Heinrichs, (Brill, 2002), 459.

- ↑ Frank Clements. Conflict in Afghanistan: a historical encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, 2003. ISBN 1-85109-402-4, ISBN 978-1-85109-402-8. Pg 181

Back to Jat Places in Afghanistan