Gedrosia

| Author:Laxman Burdak, IFS (Retd.) |

Gedrosia is the hellenized name of an area that corresponds to today's Balochistan. It may be identified with modern Gwadar in Pakistan. According to Arrian[1] the capital of Gedrosia was town named Pura.

Location

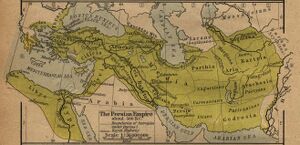

The area which is named Gedrosia, in books about Alexander the Great and his successors, runs from the Indus River to the southern edge of the Strait of Hormuz. It is directly to the south of the Iranian countries of Bactria, Arachosia and Drangiana, to the east of the Iranian countries of Persia and Carmania and due west of the Indus River which formed a natural boundary between it and Western India.

Jat clan

History

Following his army's refusal to continue marching east at the Hyphasis River in 325 BC, Alexander the Great crossed the area after sailing south to the coast of the Indian Ocean on his way back to Babylon. Upon reaching the Ocean, Alexander the Great divided his forces in half, sending half back by sea to Susa under the command of Nearchus.[2] The other half of his army was to accompany him on a march through the Gedrosian desert, inland from the ocean.[3] Throughout the 60 day march through the desert, Alexander lost at least 12,000 soldiers, in addition to countless livestock, camp followers, and most of his baggage train.[4] Some historians say he lost three-quarters of his army to the harsh desert conditions along the way.[5] However, this figure was likely based on exaggerated numbers in his forces prior to the march, which were likely in the range of no less than 30,000 soldiers.[6]

There are two competing theories for the purpose of Alexander the Great's decision to march through the desert rather than along the more hospitable coast. The first argues that this was an attempt to punish his men for their refusal to continue eastward at the Hyphasis River.[7] The other argues that Alexander was attempting to imitate and succeed in the actions of Cyrus the Great, who had failed to cross the desert.[8] The decision to cross the Gedrosian Desert, whatever his intentions, is regarded as the largest blunder in Alexander the Great's Asiatic campaign.

The march of Alexander through the desert of Gadrosia

Arrian[9] writes ... THENCE Alexander marched through the land of the Gadrosians, by a difficult route, which was also destitute of provisions; and in many places there was no water for the army. Moreover they were compelled to march most of the way by night, and a great distance from the sea. However he was very desirous of coming to the part of the country along the sea, both to see what harbours were there, and to make what preparations he could on his march for the fleet, either by employing his men in digging wells, or by making arrangetnents somewhere for a market and anchorage. But the part of the country of the Gadrosians near the sea was entirely desert. He therefore sent Thoas, son of Mandrodorus, with a few horsemen down to the sea, to reconnoitre and see if there happened to be any haven anywhere near, or whether there was water or any other of the necessaries of life not far from the sea. This man returned and reported that he found some fishermen upon the shore living in stifling huts, which were made by putting together mussel-shells, and the back-bones of fishes were used to form the roofs. He also said that these fishermen used little water, obtaining it with difficulty by scraping away the gravel,’ and that what they got was not at all fresh. When Alexander reached a certain place in Gadrosia, where corn was more abundant, he seized it and placed it upon the beasts of burden; and marking it with his own seal, he ordered it to be conveyed down to the sea. But while he was marching to the halting stage nearest to the sea, the soldiers paying little regard to the seal, the guards made use of the corn themselves, and gave a share of it to those who were especially pinched with hunger. To such a degree were they overcome by their misery that after mature deliberation they resolved to take account of the visible and already impending destruction rather than the danger of incurring the king’s wrath, which was not before their eyes and still remote. When Alexander ascertained the necessity which constrained them so to act, he pardoned those who had done the deed. He himself hastened forward to collect from the land all he could for victualling the army which was sailing round with the fleet; and sent Cretheus the Callatian to convey the supplies to the coast. He also ordered the natives to grind as much corn as they could and convey it down from the interior of the country, together with dates and sheep for sale to the soldiers. Moreover he sent Telephus, one of the confidential Companions, down to another place on the coast with a small quantity of ground corn.

Arrian[10] writes ... HE then advanced towards the capital of the Gadrosians, which was named Pura ; and he arrived there in sixty days after starting from Ora. Most of the historians of Alexander’s reign assert that all the hardships which his army suffered in Asia were not worthy of comparison with the labours undergone here. They say that Alexander pursued this route, not from ignorance of the difficulty of the journey (Nearchus, indeed, alone says that he was ignorant of it), but because he heard that no one had ever hitherto passed that way with an army and emerged in safety, except Semiramis, when she fled from India. The natives said that even she emerged with only twenty men of her army; and that Cyrus,. son of Cambyses, escaped with only seven of his men. For they say that Cyrus also marched into this region for the purpose of invading India, but that he did not effect his retreat before losing the greater part of his army, from the desert and the other difficulties of this route. When Alexander received this information he is said to have been seized with a desire of excelling Cyrus and Seniiramis. Nearchus says that he turned his march this way, both for this reason and at the same time for the purpose of conveying provisions near the fleet. The scorching heat and lack of water destroyed a great part of the army, and especially the beasts of burden; most of which perished from thirst and some of them even from the depth and heat of the sand, because it had been thoroughly scorched by the sun. For they met with lofty ridges of deep sand, not closely pressed and hardened, but such as received those who stepped upon it just as if they were stepping into mud, or rather into untrodden snow. At the same time too the horses and mules suffered still more, both in going up and coming down the hills, from the unevenness of the road as well as from its instability. The length of the marches between the stages also exceedingly distressed the army; for the lack of water often compelled them to make the marches of unusual length.’ When they travelled by night on a journey which it was necessary to complete, and at daybreak came to water, they suffered no hardship at all; but if, while still on the march, on account of the length of the way, they were caught by the heat, the day advancing, then they did indeed suffer hardships from the blazing sun, being at the same time oppressed by unassuageable thirst.

References

- ↑ Arrian Anabasis Book/6b, Ch.24

- ↑ [A.B. Bosworth, "Conquest and Empire: The Reign of Alexander the Great." 1988. pg 139]

- ↑ [Ibid, pg. 142]

- ↑ [Ibid, pg 145]

- ↑ Plutarch, The Life of Alexander, 66.

- ↑ [A.B. Bosworth, "Conquest and Empire: The Reign of Alexander the Great." 1988. pg 146]

- ↑ [Waldemar Heckel, "The Wars of Alexander the Great." 2002. pg. 68]

- ↑ [A.B. Bosworth, "Conquest and Empire: The Reign of Alexander the Great." 1988. pg 146]

- ↑ Arrian Anabasis Book/6b, Ch.23

- ↑ Arrian Anabasis Book/6b, Ch.24

Back to Jat Places in Pakistan

Back to Jat Places in Pakistan