Samsun

| Author:Laxman Burdak, IFS (R) |

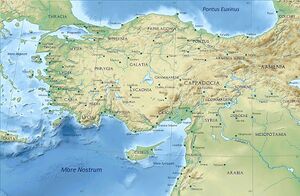

Samsun , historically known as Sampsounta (Greek: Σαμψούντα) and Amisos (Ancient Greek: Αμισός), is a city on the north coast of Turkey and is a major Black Sea port. The city is the provincial capital of Samsun Province.

Variants

- Amisus (Pliny.vi.39)

- Sampsounta (Greek: Σαμψούντα) - ounta is Greek suffix for place names

- Amisós (Αμισός) (Greek name)

- Amisos

- Amisus (Pliny.vi.2)

- Enete

- Enetoi

- Simisso

Jat clans

Name

The present name of the city is believed to have come from its former Greek name of Amisós (Αμισός) by a reinterpretation of eís Amisón (meaning "to Amisós") and ounta (Greek suffix for place names) to [eí]s Am[p]s-únta (Σαμψούντα: Sampsúnta) and then Samsun[1] (pronounced [samsun]).

The early Greek historian Hecataeus wrote that Amisos was formerly called Enete, the place mentioned in Homer's Iliad. In Book II, Homer says that the ἐνετοί (Enetoi) inhabited Paphlagonia on the southern coast of the Black Sea in the time of the Trojan War (c. 1200 BC). The Paphlagonians are listed among the allies of the Trojans in the war, where their king Pylaemenes and his son Harpalion perished.[2] Strabo mentioned that the inhabitants had disappeared by his time.[3]

Samsun has also been known as Peiraieos by Athenian settlers and even briefly as Pompeiopolis by Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus.[4]

The city was called Simisso by the Genoese. It was during the Ottoman Empire, that its present name was written as Ottoman Turkish: صامسون (Ṣāmsūn). The city has been known as Samsun since the formation of the Turkey in 1923.

History

Ancient history: Paleolithic artifacts found in the Tekkeköy Caves can be seen in Samsun Archaeology Museum.

The earliest layer excavated of the höyük of Dündartepe revealed a Chalcolithic settlement. Early Bronze Age and Hittite settlements were also found there[5] and at Tekkeköy.

Samsun (then known as Amisos, Greek Αμισός, alternative spelling Amisus) was settled in about 760–750 BC by Ionians from Miletus,[6] who established a flourishing trade relationship with the ancient peoples of Anatolia. The city's ideal combination of fertile ground and shallow waters attracted numerous traders.[7]

Amisus was settled by the Ionian Milesians in the 6th century BC,[8] it is believed that there was significant Greek activity along the coast of the Black Sea, although the archaeological evidence for this is very fragmentary.[9] The only archaeological evidence we have as early as the 6th century is a fragment of Wild Goat style Greek pottery, in the Louvre.[10]

The city was captured by the Persians in 550 BC and became part of Cappadocia (satrapy).[11] In the 5th century BC, Amisus became a free state and one of the members of the Delian League led by the Athenians;[12] it was then renamed Peiraeus under Pericles.[13] Starting the 3rd century BC the city came under the control of Mithridates I, later founder of the Kingdom of Pontus. The Amisos treasure may have belonged to one of the kings. Tumuli, containing tombs dated between 300 BC and 30 BC, can be seen at Amisos Hill but unfortunately Toraman Tepe was mostly flattened during construction of the 20th century radar base.[14]

The Romans conquered Amisus in 71 BC during the Third Mithridatic War.[15] and Amisus became part of Bithynia et Pontus province. Around 46 BC, during the reign of Julius Caesar, Amisus became the capital of Roman Pontus.[16] From the period of the Second Triumvirate up to Nero, Pontus was ruled by several client kings, as well as one client queen, Pythodorida of Pontus, a granddaughter of Marcus Antonius. From 62 CE it was directly ruled by Roman governors, most famously by Trajan's appointee Pliny. Pliny the Younger's address to the Emperor Trajan in the 1st century CE "By your indulgence, sir, they have the benefit of their own laws," is interpreted by John Boyle Orrery to indicate that the freedoms won for those in Pontus by the Romans was not pure freedom and depended on the generosity of the Roman emperor.[17]

The estimated population of the city around 150 AD is between 20,000 and 25,000 people, classifying it as a relatively large city for that time.[18] The city functioned as the commercial capital for the province of Pontus; beating its rival Sinope (now Sinop) due to its position at the head of the trans-Anatolia highway.[19]

In Late Antiquity, the city became part of the Dioecesis Pontica within the eastern Roman Empire; later still it was part of the Armeniac Theme.[20]

Samsun Castle was built on the seaside in 1192, it was demolished between 1909 and 1918.

Mention by Pliny

Pliny[21] mentions...We then come to the river Evarchus13, and after that a people of the Cappadocians, the towns of Gaziura14 and Gazelum15, the river Halys16, which runs from the foot of Mount Taurus through Cataonia and Cappadocia, the towns of Gangre17 and Carusa18, the free town of Amisus19, distant from Sinope one hundred and thirty miles, and a gulf of the same name....

13 The boundary, according to Stephanus Byzantinus, also of the nations of Paphlagonia and Cappadocia. As Parisot remarks, this is an error, arising from the circumstance of a small tribe bearing the name of Cappadocians, having settled on its banks, between whom and the Paphlagonians it served as a limit.

14 On the river Iris. It was the ancient residence of the kings of Pontus, but in Strabo's time it was deserted. It has been suggested that the modern Azurnis occupies its site.

15 In the north-west of Pontus, in a fertile plain between the rivers Halys and Amisus. It is also called Gadilon by Strabo. D'Anville makes it the modern Aladgiam; while he calls Gaziura by the name of Guedes.

16 Now called the Kisil Irmak, or Red River. It has been remarked that Pliny, in making this river to come down from Mount Taurus and flow at once from south to north, appears to confound the Halys with one of its tributaries, now known as the Izchel Irmak.

17 Its site is now called Kiengareh, Kangreh, or Changeri. This was a town of Paphlagonia, to the south of Mount Olgasys, at a distance of thirty-five miles from Pompeiopolis.

18 A commercial place to the south of Sinope. Its site is the modern Gherseh on the coast.

19 Now called Eski Samsun; on the west side of the bay or gulf, anciently called Sinus Amisenus. According to Strabo, it was only 900 stadia from Sinope, or 112 1/2 Roman miles. The walls of the ancient city are to be seen on a promontory about a mile and a half from the modern town.

See also

References

- ↑ Özhan Öztürk. Karadeniz: Ansiklopedik Sözlük (Blacksea: Encyclopedic Dictionary) Archived 13 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine. 2 Cilt (2 Volumes). Heyamola Publishing. Istanbul. 2005 ISBN 975-6121-00-9

- ↑ Homer, Iliad; online version at classics.mit.edu, accessed on 2009-08-18. Book II

- ↑ Strab. 12.3

- ↑ "Samsun Guide" (PDF).

- ↑ "..:: REPUBLIC OF TURKEY MINISTRY OF CULTURE AND TOURISM ::."

- ↑ "..:: REPUBLIC OF TURKEY MINISTRY OF CULTURE AND TOURISM ::."

- ↑ Cohen, Getzel M. (1995). "The Hellenistic Settlements in Europe, the Islands, and Asia Minor". Berkeley and Los Angeles: California: University of California Press. p. 384.

- ↑ Wilson, M. W. "Cities of God in Northern Asia Minor: Using Stark's Social Theories to Reconstruct Peter's Communities". Verbum et Ecclesia 32 (1). p. 3.

- ↑ Topalidis, S. "Formation of the First Greek Settlements in the Pontos". Pontos World. Pontosworld.com.

- ↑ Tsetskhladze, G.R. (1998 ) "The Greek Colonisation of the Black Sea Area: Historical Interpretation of Archaeology". Stuttgart: F. Steiner. p. 19.; Louvre page

- ↑ "Samsun Guide" (PDF).

- ↑ Wilson, M. W. "Cities of God in Northern Asia Minor: Using Stark's Social Theories to Reconstruct Peter's Communities". Verbum et Ecclesia 32 (1). p. 4.

- ↑ Jones, A.H.M (1937). "The Cities of the Eastern Roman Provinces". Oxford: The Clarendon Press. p. 149.

- ↑ "ESKİ SAMSUN' DA (AMİSOS) AYDINLANAN TARİH".

- ↑ "Antik Amisos Kenti".

- ↑ Wilson, M. W. "Cities of God in Northern Asia Minor: Using Stark's Social Theories to Reconstruct Peter's Communities". Verbum et Ecclesia 32 (1). p. 3.

- ↑ Orrery, J. B. (1752). "The Letters of Pliny the Younger: With Observations on Each Letter; and an Essay on Pliny's Life, Addressed to Charles Lord Boyle". The 3rd ed. London: Printed by James Bettenham, for Paul Vaillant. p. 407.

- ↑ Mitchell, S. (1995). "Anatolia: Land, Men, and Gods in Asia Minor". Journal of Roman Studies, 85. pp. 301–302

- ↑ Wilson, M. W. "Cities of God in Northern Asia Minor: Using Stark's Social Theories to Reconstruct Peter's Communities". Verbum et Ecclesia 32 (1). p. 4.

- ↑ Giftopoulou Sofia (17 March 2003). "Amisos (Byzantium)". Encyclopaedia of the Hellenic World, Asia Minor. Translated by Koutras Nikolaos.

- ↑ Natural History by Pliny Book VI/Chapter 2

Back to Jat Places in Turkey/Back to Jat Places in Anatolia