Lesser Armenia

| Author: Laxman Burdak, IFS (R) |

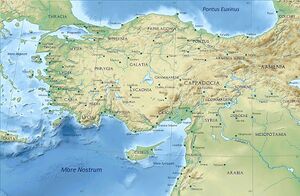

Lesser Armenia, also known as Armenia Minor and Armenia Inferior, comprised the Armenian-populated regions primarily to the west and northwest of the ancient Kingdom of Armenia (also known as Kingdom of Greater Armenia), on the western side of the Euphrates River. It was also a kingdom, separate from Greater Armenia, from the 2nd century BC to the 1st century AD. The region was later reorganized into the Armeniac Theme under the Byzantine Empire.

Variants

- Lesser Armenia (Pliny.vi.10)

- Armenia Minor

- Armenian: Փոքր Հայք,

- romanized: P’ok’r Hayk’;[1]

- Latin: Armenia Minor;

- Ancient Greek: μικρά Αρμενία, romanized: mikrá Armenía[2]

- Armenia Inferior

Jat Gotras Namesake

- Hayal = Hayk = Lesser Armenia (Pliny.vi.10)

Mention by Pliny

Pliny[3] mentions The Rivers Cyrus and Araxes....The more famous towns in Lesser Armenia are Cæsarea3, Aza4, and Nicopolis5; in the Greater Arsamosata6, which lies near the Euphrates, Carcathiocerta7 upon the Tigris, Tigranocerta8 which stands on an elevated site, and, on a plain adjoining the river Araxes, Artaxata.9

3 Hardouin thinks that this is Neo-Cæsarea, mentioned as having been built on the banks of the Euphrates.

4 Now called Ezaz, according to D'Anville. Parisot suggests that it ought to be Gaza or Gazaca, probably a colony of Median Gaza, now Tauris.

5 Originally called Tephrice. It stood on the river Lycus, and not far from the sources of the Halys, having been founded by Pompey, where he gained his first victory over Mithridates, whence its name, the "City of Victory." The modern Enderez or Devrigni, probably marks its site.

6 Ritter places it in Sophene, the modern Kharpat, and considers that it may be represented by the modern Sert, the Tigranocerta of D'Anville.

7 The capital of Sophene, one of the districts of Armenia. St. Martin thinks that this was the ancient heathen name of the city of Martyropolis, but Ritter shows that such cannot be the case. It was called by the Syrians Kortbest; its present name is Kharput.

8 Generally supposed, by D'Anville and other modern geographers, to be represented by the ruins seen at Sert. It was the later capital of Armenia, built by Tigranes.

9 The ancient capital of Armenia. Hannibal, who took refuge at the court of Artaxias when Antiochus was no longer able to afford him protection, superintended the building of it. Some ruins, called Takt Tiridate, or Throne of Tiridates, near the junction of the Aras and the Zengue, were formerly supposed to represent Artaxata, but Colonel Monteith has fixed the site at a bend in the river lower down, at the bottom of which were the ruins of a bridge of Greek or Roman architecture.

Geography

Lesser Armenia (or Armenia Minor) was the portion of historic Armenia and the Armenian Highlands lying west and northwest of the river Euphrates.[4] It received its name to distinguish it from the much larger eastern portion of historic Armenia—Greater Armenia (or Armenia Major).

Early history

Lesser Armenia corresponded to the location of the Late Bronze Age Hayasa-Azzi confederation, which is thought by some scholars to be the source of the Armenian endonym hay and the original state of the Proto-Armenians.[5] It has been suggested that the epithet "lesser" indicates that this territory was the older homeland of the Armenian people, while "greater" Armenia referred to a territory that was later settled.[6][7]

Lesser Armenia may have formed a part of the territories of the Orontid dynasty, which ruled Armenia first as satraps of the Achaemenid Empire and then as kings.[8] However, there is no clear evidence to support this claim.[9] Lesser Armenia emerged as a separate kingdom after the Treaty of Apamea in 188 BC, although the exact origin, size and history of this kingdom are murky.[10] The capital of this kingdom was probably originally at Kamakh, but likely moved to Nicopolis after the end of the Mithridatic Wars.[11] Lesser Armenia apparently experienced the high point of its territorial expansion during the Orontid period, possibly expanding its borders to the Black Sea.[12]

According to Strabo, it originally had its own royal dynasty.[13] It passed under the control of the Kingdom of Pontus in the 1st century BC, during the reign of Mithridates VI Eupator (r. 120 – 63 BC), who built 75 fortresses there.[14]

After the Romans defeated Pontus in the Mithridatic Wars, Lesser Armenia became a client kingdom of Rome, who appointed various client kings to rule the kingdom.[15] The last of these was Aristobulus of Chalcis of the Herodian dynasty.[16]

In 72 AD, Lesser Armenia was annexed by the Roman Empire and made a part of the larger province of Cappadocia.[17]

Roman and Byzantine Lesser Armenia

All of Armenia became a Roman province in AD 114 under Roman emperor Trajan, but Roman Armenia was soon after abandoned by the legions in 118 AD and became a vassal kingdom. Lesser Armenia, however, was generally incorporated by Trajan, together with Miletene and Cataonia, into the province of Cappadocia.

Lesser Armenia consisted of five districts: Orbalisene in the North; below that Aetulane; Aeretice; then Orsene; and finally Orbesine, the most southern. The more southern districts appended to Lesser Armenia were Miletene, so called from its capital (the modern Malatya) and the following four small districts of ancient Cataonia, namely, Aravene; Lavinianesine or Lavianesine; Cataonia, in the more restricted sense, or the country close upon Cilicia surrounded by mountains; finally, Muriane or Murianune, between Cataonia and Melitene, called likewise Bagadoania.[18]

Lesser Armenia was reunited with the kingdom of Greater Armenia under the Arshakuni king Tiridates III in AD 287 until the temporary conquest of Shapur II in 337.

Then it was formed into a regular province under Diocletian, and in the 4th century, was divided in two provinces: First Armenia (Armenia Prima), which contained most of Lesser Armenia, and Second Armenia (Armenia Secunda) that comprised all the southern tracts which had been added to Lesser Armenia, with the exception of Cataonia, which was incorporated with Cappadocia Secunda.[19]

Its population remained Armenian but was being gradually Romanized. Since the 3rd century many Armenian soldiers were in the Roman army: later–in the 4th century–they made up two Roman legions, the Legio I Armeniaca and the Legio II Armeniaca.

In 536, the emperor Justinian I reorganized the provincial administration, and First and Second Armenia were renamed Second and Third respectively, while some of their territory was split off to the other Armenian provinces.

The borders of the Byzantine part of Armenia were expanded in 591 into Persarmenia, but the region was the focus of decades of warfare between the Byzantines and the Persians (the Byzantine-Sassanid Wars) until the Arab conquest of Armenia in 639.

After this, the part of Lesser Armenia remaining under Byzantine control (in a lesser extent) became part of the theme of Armeniakon.

External links

References

- ↑ Adontz, Nicolas (1970). The Reform of Justinian Armenia. Lisbon: Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation.p.311

- ↑ Harut῾yunyan, B. (1986). "P῾OK῾R HAYK῾". Haykakan sovetakan hanragitaran (in Armenian). Vol. 12. Erewan. p. 373a

- ↑ Natural History by Pliny Book VI/Chapter 10

- ↑ Harut῾yunyan, B. (1986). "P῾OK῾R HAYK῾". Haykakan sovetakan hanragitaran (in Armenian). Vol. 12. Erewan. p. 373a

- ↑ Петросян, Армен (2014). Арменоведческие исследования (in Russian). Ереван: Антарес. ISBN 978-9939-51-697-4.p.108

- ↑ Петросян 2014, p. 108.

- ↑ Petrosyan, Armen (2007). "The Problem Of Identification Of The Proto-Armenians: A Critical Review". Journal of the Society for Armenian Studies. p. 43.

- ↑ Hewsen, Robert H. (2001). Armenia: A Historical Atlas. University Of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-33228-4.p.32

- ↑ Hewsen 2001, p. 32.

- ↑ Hewsen 2001, pp. 32, 37.

- ↑ Hewsen 2001, pp. 32, 37.

- ↑ Hewsen 2001, p. 32.

- ↑ Hewsen 2001, p. 37.

- ↑ Hewsen 2001, p. 37.

- ↑ Hewsen 2001, p. 37.

- ↑ Hewsen 2001, p. 37.

- ↑ Hewsen 2001, pp. 37, 48.

- ↑ Peter Edmund Laurent (1830). An Introduction to the Study of Ancient Geography. With copious indexes. Oxford: Henry Slatter. pp. 233–234.

- ↑ Peter Edmund Laurent (1830). An Introduction to the Study of Ancient Geography. With copious indexes. Oxford: Henry Slatter. p. 234.

Back to Jat Places in Armenia