Malabar

| Author:Laxman Burdak, IFS (R) |

Malabar Coast is the southwestern coast of the Indian subcontinent. Geographically, it comprises the wettest regions of southern India, as the Western Ghats intercept the moisture-laden monsoon rains, especially on their westward-facing mountain slopes.

Variants

Location

Malabar Coast, name long applied to the southern part of India’s western coast, approximately from the state of Goa southward, which is bordered on the east by the Western Ghats range. The term is used to refer to the entire Indian coast from the western coast of Konkan to the tip of the subcontinent at Kanyakumari.[1]

Jat clans

Etymology

The whole name Malabar is first attested in Arabic (as malabaar) in the writing of Al Biruni. The second part of the name is thought by scholars to be the Arabic word barr ('continent') or its Persian relative bar ('country'). The first element of the name, however, is attested already in the Topography written by Cosmas Indicopleustes in the sixth century CE. This mentions a pepper emporium called Male, which clearly gave its name to Malabar ('the country of Male'). The name male is thought to come from the Malayalam word mala ('hill').[2]

Until the arrival of British, the term Malabar was used in foreign trade circles as a general name for Kerala.[3] Earlier, the term Malabar had also been used to denote Tulu Nadu and Kanyakumari which lie contiguous to Kerala in the southwestern coast of India, in addition to the modern state of Kerala.[4] The people of Malabar were known as Malabars. Still the term Malabar is often used to denote the entire southwestern coast of India. From the time of Cosmas Indicopleustes (6th century CE) itself, the Arab sailors used to call Kerala as Male. The first element of the name, however, is attested already in the Topography written by Cosmas Indicopleustes. This mentions a pepper emporium called Male, which clearly gave its name to Malabar ('the country of Male'). The name Male is thought to come from the Malayalam word Mala ('hill').[5] Al-Biruni (AD 973 - 1048) must have been the first writer to call this state Malabar.[6] Authors such as Ibn Khordadbeh and Al-Baladhuri mention Malabar ports in their works.[7] The Arab writers had called this place Malibar, Manibar, Mulibar, and Munibar. Malabar is reminiscent of the word Malanad which means the land of hills. According to William Logan, the word Malabar comes from a combination of the Malayalam word Mala (hill) and the Persian/Arabic word Barr (country/continent).[8]

History

Prehistory: A substantial portion of Malabar Coast including the western coastal lowlands and the plains of the midland may have been under the sea in ancient times. Marine fossils have been found in an area near Changanassery, thus supporting the hypothesis.[9] Pre-historical archaeological findings include dolmens of the Neolithic era in the Marayur area of the Idukki district, which lie on the eastern highland made by Western Ghats. Rock engravings in the Edakkal Caves, in Wayanad date back to the Neolithic era around 6000 BCE.[10]

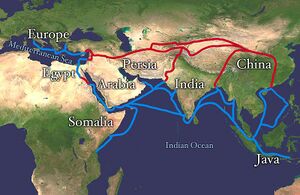

Ancient and medieval history: Malabar Coast has been a major spice exporter since 3000 BCE, according to Sumerian records and it is still referred to as the "Garden of Spices" or as the "Spice Garden of India".[11] Kerala's spices attracted ancient Arabs, Babylonians, Assyrians and Egyptians to the Malabar Coast in the 3rd and 2nd millennia BCE. Phoenicians established trade with Malabar during this period. Arabs and Phoenicians were the first to enter Malabar Coast to trade Spices. The Arabs on the coasts of Yemen, Oman, and the Persian Gulf, must have made the first long voyage to Malabar and other eastern countries. They must have brought the Cinnamon of Malabar to the Middle East. The Greek historian Herodotus (5th century BCE) records that in his time the cinnamon spice industry was monopolized by the Egyptians and the Phoenicians.[12]

According to the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, a region known as Limyrike began at Naura and Tyndis. However the Ptolemy mentions only Tyndis as the Limyrike's starting point. The region probably ended at Kanyakumari; it thus roughly corresponds to the present-day Malabar Coast. The value of Rome's annual trade with the region was estimated at around 50,000,000 sesterces. Pliny the Elder mentioned that Limyrike was prone by pirates.[13] The Cosmas Indicopleustes mentioned that the Limyrike was a source of Malabar peppers.[14] In the last centuries BCE the coast became important to the Greeks and Romans for its spices, especially Malabar pepper. The Cheras had trading links with China, West Asia, Egypt, Greece, and the Roman Empire.[15] In foreign-trade circles the region was known as Male or Malabar.[16] Muziris, Tyndis, Naura (near Kannur), and Nelcynda were among the principal ports at that time.[17] contemporary Sangam literature describes Roman ships coming to Muziris in Kerala, laden with gold to exchange for Malabar pepper. One of the earliest western traders to use the monsoon winds to reach Kerala was Eudoxus of Cyzicus, around 118 or 166 BCE, under the patronage of Ptolemy VIII, king of the Hellenistic Ptolemaic dynasty in Egypt. Roman establishments in the port cities of the region, such as a temple of Augustus and barracks for garrisoned Roman soldiers, are marked in the Tabula Peutingeriana, the only surviving map of the Roman cursus publicus.[18]

The term Kerala was first epigraphically recorded as Keralaputo (Cheras) in a 3rd-century BCE rock inscription by emperor Ashoka of Magadha.[19] It was mentioned as one of four independent kingdoms in southern India during Ashoka's time, the others being the Cholas, Pandyas and Satyaputras.[20] The Cheras transformed Kerala into an international trade centre by establishing trade relations across the Arabian Sea with all major Mediterranean and Red Sea ports as well those of the Far East. The dominion of Cheras was located in one of the key routes of the ancient Indian Ocean trade. The early Cheras collapsed after repeated attacks from the neighboring Cholas and Rashtrakutas.

During the early Middle Ages, Namboodiri Brahmin immigrants arrived in Kerala and shaped the society on the lines of the caste system. In the 8th century, Adi Shankara was born at Kalady in central Kerala. He travelled extensively across the Indian subcontinent founding institutions of the widely influential philosophy of Advaita Vedanta. The Cheras regained control over Kerala in the 9th century until the kingdom was dissolved in the 12th century, after which small autonomous chiefdoms, most notably the Kingdom of Kozhikode, arose. The 13th century Venetian explorer, Marco Polo, would visit an write of his stay in the province.[21] The port at Kozhikode acted as the gateway to medieval South Indian coast for the Chinese, the Arabs, the Portuguese, the Dutch, and finally the British.[22]

In 1498, Vasco Da Gama established a sea route to Kozhikode during the Age of Discovery, which was also the first modern sea route from Europe to South Asia, and raised Portuguese settlements, which marked the beginning of the colonial era of India. European trading interests of the Dutch, French and the British East India companies took centre stage during the colonial wars in India. Travancore became the most dominant state in Kerala by defeating the powerful Zamorin of Kozhikode in the battle of Purakkad in 1755.[23] After the Dutch were defeated by Travancore king Marthanda Varma, the British crown gained control over Kerala through the creation of the Malabar District in northern Kerala and by allying with the newly created princely state of Travancore in the southern part of the state until India was declared independent in 1947. The state of Kerala was created in 1956 from the former state of Travancore-Cochin, the Malabar district and the Kasaragod taluk of South Canara District of Madras state.[24]

Nagavanshi History

Dr Naval Viyogi[25] writes.... Kashmir to Assam, Himalyan ranges have been the largest centre of the abode of Naga race since dark age of prehistoric time. But their traces are still visible in the form of ethnic groups, social and religious traditions, old architectural remains, inscriptions, coins, name of cities and places all over India.

In some parts of Ceylon and in ancient Malabar country , ancient Nagas established their rule. The Tamil literature of first century A.D. has repeated description of Naga-Nadu or the Country of Nagas. Still today Malabar coast is one of the largest Centres Naga Worship. In South, Travancore temple of Nagercoil[26] is famous.

CF. Oldham has thrown much light on this subject. He writes[27] "The Dravidians were divided into Chera, Choru and Pandyas in ancient time. Chera or Sera (in ancient Tamil Sarai is synonym of serpent in Dravidian language. It is clear from the words like Chera-Mandel (Coromandal) Naga-Dipa (serpent Island), and Naga-Nadu (Naga country) that Dravidians of South were of Asura or Naga family. In addition to the above, the Cheru or Sirai had also spread in all the Gangatic valley, which are in existence still to-day. They maintain their origin from some Naga deity or Devta. (Elliot, sup Glossary N. W. F. PP 135-36) Cherus are most ancient people. They possessed a large part of Gangatic valley and lived there from time immemorial. During the incendiary, time of the Muslim invaders, Cherus were forced to draw hands from their lands and now they are landless people. They are undoubtedly blood relatives of Dravidian Cheras."

External links

References

- ↑ https://www.britannica.com/place/Malabar-Coast

- ↑ C. A. Innes and F. B. Evans, Malabar and Anjengo, volume 1, Madras District Gazetteers (Madras: Government Press, 1915), p. 2.

- ↑ Sreedhara Menon, A. (January 2007). Kerala Charitram (2007 ed.). Kottayam: DC Books. ISBN 9788126415885.

- ↑ J. Sturrock (1894). "Madras District Manuals - South Canara (Volume-I)". Madras Government Press.

- ↑ C. A. Innes and F. B. Evans, Malabar and Anjengo, volume 1, Madras District Gazetteers (Madras: Government Press, 1915), p. 2.

- ↑ Sreedhara Menon, A. (January 2007). Kerala Charitram (2007 ed.). Kottayam: DC Books. ISBN 9788126415885.

- ↑ Mohammad, K.M. "Arab relations with Malabar Coast from 9th to 16th centuries" Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. Vol. 60 (1999), pp. 226–34.

- ↑ Sreedhara Menon, A. (January 2007). Kerala Charitram (2007 ed.). Kottayam: DC Books. ISBN 9788126415885.

- ↑ A Sreedhara Menon (2007). A Survey Of Kerala History. DC Books. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-8126415786.

- ↑ Subodh Kapoor (2002). The Indian Encyclopaedia. Cosmo Publications. p. 2184. ISBN 978-8177552577.

- ↑ Pradeep Kumar, Kaavya (28 January 2014). "Of Kerala, Egypt, and the Spice link". The Hindu.

- ↑ A Sreedhara Menon (1 January 2007). A Survey Of Kerala History. DC Books. pp. 57–58. ISBN 978-81-264-1578-6.

- ↑ Bostock, John (1855). "26 (Voyages to India)". Pliny the Elder, The Natural History. London: Taylor and Francis.

- ↑ Indicopleustes, Cosmas (1897). Christian Topography. 11. United Kingdom: The Tertullian Project. pp. 358–373.

- ↑ Cyclopaedia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia. Ed. by Edward Balfour (1871), Second Edition. Volume 2. p. 584.

- ↑ Joseph Minattur. "Malaya: What's in the name" (PDF). siamese-heritage.org. p. 1.

- ↑ K. K. Kusuman (1987). A History of Trade & Commerce in Travancore. Mittal Publications. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-8170990260.

- ↑ Abraham Eraly (2011). The First Spring: The Golden Age of India. Penguin Books India. pp. 246–. ISBN 978-0670084784.

- ↑ "Kerala." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Encyclopedia Britannica Inc., 2011.

- ↑ Vincent A. Smith; A. V. Williams Jackson (30 November 2008). History of India, in Nine Volumes: Vol. II – From the Sixth Century BCE to the Mohammedan Conquest, Including the Invasion of Alexander the Great. Cosimo, Inc. pp. 166–. ISBN 978-1-60520-492-5.

- ↑ https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Travels_of_Marco_Polo/Book_3/Chapter_17

- ↑ Sreedhara Menon, A. (January 2007). Kerala Charitram (2007 ed.). Kottayam: DC Books. ISBN 9788126415885.

- ↑ Shungoony Menon, P. (1878). A History of Travancore from the Earliest Times (pdf). Madras: Higgin Botham & Co. pp. 162–164.

- ↑ "The land that arose from the sea". The Hindu. 1 November 2003.

- ↑ Nagas, The Ancient Rulers of India, Their Origins and History, 2002, p. 32-33

- ↑ Proceedings of the 7th All India Oriental conference PP 248-49

- ↑ Oldham CF.; "The Sun and the Serpent" PP.157 and 191