Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists/CHAPTER VII

| Wikified by Laxman Burdak, IFS (Retd.) |

The Churning of the Ocean

IT happened long ago that Indra, king of the gods, was cursed by the great rishi Durvasas, a portion of Shiva, for a slight he put on him. Thenceforward Indra and all the three worlds lost their energy and strength, and all things went to ruin. Then the daityas or asuras put forth their strength against the enfeebled gods, so that they fled to Brahma for protection ; he then advised them to seek aid from Vishnu, the tamer of demons, the undying God, creator, preserver, and destroyer. So Brahma spoke, and himself led the gods along the northern shore of the sea of milk to Vishnu's seat, and prayed his aid. Then the Supreme Deity, bearing his emblems of conch and disc and mace, and radiant with light, appeared before the grandsire and other deities, and to him again they all made prayer. Then Hari smiled and said : " I shall restore your strength. Do now as I command : Cast into the Milky Sea potent herbs, then take Mount Mandara for churning-stick, the serpent Vasuki for rope, and churn the ocean for the dew of life. For this you need the daityas' aid ; make alliance with them, therefore, and engage to share with them the fruit of your combined labour ; promise them that by drinking the ambrosia they shall become immortal. But I shall see to it that they have no share of the water of life, but theirs shall be the labour only."

Thus the gods entered into alliance with the demons, and jointly undertook the churning of the sea of milk. They cast into it potent herbs, they took Mount Mandara for

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 314

the churning-stick and Vasuki for the rope. 1 The gods took up their station by the serpent's tail, the daily as at its head. Hari himself in tortoise shape became a pivot of the mountain as it was whirled around ; he was present also unseen amongst the gods and demons, pulling the serpent to and fro ; in another vast body he sat upon the summit of the mountain. With other portions of his energy he sustained the serpent king, and infused power into the bodies of the gods. As they laboured thus the flames of Vasuki's breath scorched the faces of the demons; but the clouds that drifted toward his tail refreshed the gods with vivifying showers.

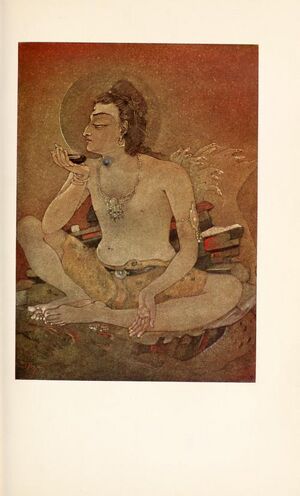

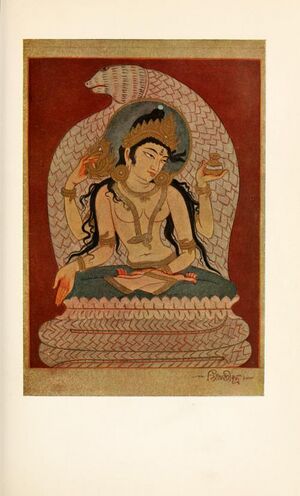

First from the sea rose up the wish-bestowing cow Surabhi, gladdening the eyes of the divinities ; then came the goddess Varuni, with rolling eyes, the divinity of wine ; then upsprang the Parijata tree of paradise, the delight of Heaven's nymphs, perfuming all the world with the fragrance of its flowers; then rose the troops of apsaras, of entrancing loveliness and grace. Then rose the moon, whom Mahadeva seized and set upon his brow ; and then came a draught of deadly poison, and that also Mahadeva took and drank, lest it should destroy the world : it is that bitter poison that turned his throat blue, wherefore he is known as Nilakantha, blue-throat, ever after. Next came Dhanwantari, holding in his hand a cup of the dew of life, delighting the eyes of the daityas and the rishis. Then appeared the goddess Shri, the delight of Vishnu, radiant, seated on an open lotus ; the great sky-elephants anointed her with pure

1. The Indian milk-churn is a stick round which a long rope is twisted, and pulled alternately from opposite ends. The rope itself holds up the stick in a vertical position, and the turning of it to and fro accomplishes the churning.

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 315

water brought by Ganga and poured from golden vessels, while the enraptured sages sang her praises. The Milky Sea adorned her with a wreath of unfading flowers; Vishvakarma decked her with celestial jewels. Then she, who was in sooth the bride of Vishnu, cast herself upon his breast, and there reclining turned her eyes upon the delighted gods. But little pleased were the daityas, for now were they abandoned by the goddess of prosperity. The angry daityas snatched the cup of nectar from Dhanwantari and bore it off. But Vishnu, assuming an exquisite and ravishing woman-form, deluded and fascinated them, and while they disagreed amongst themselves he stole away the draught and brought it to the gods, who drank deep from the cup of life. In vigorated thereby, they put the demons to flight and drove them down to Hell, and worshipped Vishnu with rejoicing. The sun shone clear again, the Three Worlds became once more prosperous, and devotion blossomed in the hearts of every creature. Indra, seated upon his throne, composed a hymn of praise for Lakshmi ; she, thus praised, granted him wishes twain. This was the choice, that never again should she abandon the Three Worlds, nor should she ever forsake any that should sing her praise in the words of Indra's hymn. Who so hears this story of the birth of Lakshmi from the Milky Sea, whosoever reads it, that goddess of good fortune shall never leave his house for generations three; strife or misfortune may never enter where the hymn toLakshmi is sung.

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 316

The Birth of Ganga

There was once a king of Ayodhya, by name Sagara. He eagerly desired children, but had no issue. His elder wife was Keshini, the second Sumati, sister of Garuda. With these twain he came to Himalaya to practise an austere penance. When a hundred years had passed, the rishi Brigu, whom he had honoured, granted him his wish. " Thou shalt attain unparalleled renown amongst men," he said. "One wife of thine, Keshini, shall bring forth a son who will perpetuate thy race ; the other shall give birth to sixty thousand sons." Those daughters of kings were glad, and worshipping the rishi, they asked: "Who of us shall have one son and who many we would know." He asked their will. " Who wishes for which boon?" he said, " a single perpetuator of the line, or sixty thousand famous sons, who yet shall not carry on their race ? " Then Keshini chose the single son, and Garuda's sister chose the many. Thereafter the king revered the saint with circumambulation and obeisance and returned again to his city.

In due course Keshini bore a son, to whom was given the name of Asamanja. Sumati bore a gourd, and when it burst open the sixty thousand sons came forth ; the nurses fostered them in jars of ghee until they grew up to youth and beauty. But the eldest son, the child of Keshini, loved them not, but would cast them in the Sarayu river and watch them sink. For this evil disposition and for the wrongs he did to citizens and honest folk Asamanja was banished by his father. But he had himself a son named Suman, fair-spoken to all and well-beloved. When many years had passed Sagara determined to celebrate a mighty sacrifice. The place thereof was in

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 317

the region between Himalaya and Vindhya. There the horse was loosed, and Anshumat, a mighty chariot-fighter, followed to protect it. But it befell that a certain Vasava, assuming the form of a rakshasi, stole the horse away. Then the Brahman priests informed the king, and commanded him to slay the thief and bring back the horse, lest the sacrifice should fail and misfortune should follow all concerned.

Then Sagara sent forth his sixty thousand sons to seek the horse. " Search ye the whole sea-girt earth," he said, " league by league, above the ground or under it." Then those great princes ranged the earth. Finding not the horse upon its surface, they began to delve with hands like thunderbolts and mighty ploughshares, so that the earth cried out in pain. Great was the uproar of the serpents and the demons that were slain then. For sixty thousand leagues they dug as if they would reach the very lowest deep. They undermined all Jambudwipa, so that the very gods feared and went into counsel unto Brahma. " O great grandsire," they said, " the sons of Sagara are digging out the whole earth and many are slain therefor. Crying that one hath stolen Sagara's horse, they are bringing havoc on every creature." Then Brahma answered : " This entire earth is Vasudeva's consort ; he is indeed her lord, and in the form of Kapila sustains her. By his wrath the sons of Sagara will be slain. The far- sighted have foreseen the fated digging out of earth and the death of Sagara's sons ; therefore ye should not fear." Then having riven the entire earth and ranged it all about, the sons returned to Sagara and asked what they should do, for they could not find the horse. But he commanded them again to burrow in the earth and find the horse. " Then cease," he said, " not before." Again they

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 318

plunged into the depths. There they came on the elephant Virupaksha, who bears on his head the whole world with its hills and forests, and when he shakes his head that is an earthquake. Him they duly worshipped and passed on. To the south they came next, to another mighty elephant, Mahapadma, like a mountain, bearing the earth upon his head; in like wise they came also to the western elephant named Saumanasa, and thence to the north, where is Bhadra, white as snow, bearing the earth upon his brow. Passing him by with honour, they came to the quarter east of north ; there they beheld the eternal Vasudeva in the shape of Kapila, and hard by him they saw the horse browsing at his will. They rushed on Kapila in fury, attacking him with trees and boulders, spades and ploughs, crying: "Thou art the thief; now thou hast fallen into the hands of the sons of Sagara." But Kapila uttered a dreadful roar and flashed a burning flame upon the sons that burned them all to ashes. No news of this came back to Sagara.

Then Sagara addressed his grandson Suman, bidding him seek his uncles and learn their fate, " and," said he, " there be strong and mighty creatures dwelling in earth ; honour such as do not hinder thee, slay those that stand against thee, and return, accomplishing my desire." He came in turn to the elephants of east and south and west and north, and each assured him of success ; at last he came to the heap of ashes that had been his uncles ; there he wailed with heavy heart in bitter grief. There, too, he beheld the wandering horse. He desired to perform the funeral lustrations for the uncles, but he might find no water anywhere. Then he beheld Garuda passing through the air; he cried to Anshumat: "Do not lament; for these to have been destroyed is for the good of all. The

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 319

great Kapila consumed these mighty ones ; therefore thou shouldst not make for them the common offerings of water. But there is Ganga, daughter of Himalaya ; let that purifier of every world lave this heap of ashes ; then shall the sixty thousand sons of Sagara attain to Heaven. Do thou also take back the horse and bring to completion thy grandfather's sacrifice." Then Anshumat led back the horse, and Sagara's ceremony was completed ; but he knew not how to bring to earth the daughter of Himalaya. Sagara died and Anshumat was chosen king. He was a great ruler, and at last resigned the kingdom to his son and retired to dwell alone in the Himalayan forests; in due time he also passed away and reached Heaven. His son, King Dilipa, constantly pondered how to bring down Ganga, that the ashes might be purified and Sagara's sons attain to Heaven. But after thirty thousand years he, too, died, and his son Bhagiratha, a royal saint, followed him. Ere long he consigned the kingdom to the care of a counsellor and went to the Himalayan forests, performing terrible austerities for a thousand years to draw down Ganga from the skies. Then Brahma was pleased by his devotion, and appeared before him, granting a boon. He prayed that the ashes of the sons of Sagara should be washed by the water of Ganga, and that a son might speedily be born to him. "Great is thy aim," replied the grandsire, "but thou shouldst invoke Mahadeva to receive the falling Ganga, for earth may not sustain her. None but he who sways the trident may sustain her fall."

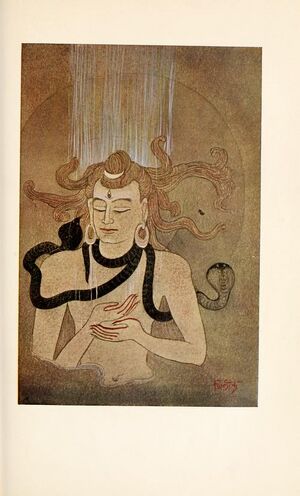

Then for a year Bhagiratha worshipped Shiva; and he, well pleased, undertook to bear the mountain-daughter's fall, receiving the river upon his head. Then Ganga, in mighty torrent, cast herself down from Heaven on to Shiva's gracious head, thinking in her pride : " I shall

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 320

sweep away the Great God in my waters, down to the nether regions." But when Ganga fell on Shiva's tangled locks she might not even reach the earth, but wandered there unable to escape for many a long year. Then Bhagiratha again engaged in many hard austerities, till Shiva would set the river free ; she fell in seven streams, three to the east, three to the west, while one followed after Bhagiratha's car. The falling waters made a sound like thunder; very wonderful the earth appeared, covered with fallen and falling fishes, tortoises, and porpoises. Devas, rishis, gandharvas, and yakshas witnessed the great sight from their elephants and horses and self-moving chariots ; every creature marvelled at the coming down of Ganga. The presence of the shining devas and the brightness of their jewels lit up the sky as if with a hundred suns. The heavens were filled with speeding porpoises and fishes like flashes of bright lightning ; the flakes of pale foam seemed like snow-white cranes crossing heavy autumn clouds. So Ganga fell, now directly onward, now aside, sometimes in many narrow streams, and again in one broad torrent ; now ascending hills, then falling again into a valley. Very fair was that vision of the water falling from Heaven to Shankara's head, and from Shankara's head to earth. All the shining ones of Heaven and all the creatures of the earth made haste to touch the sacred waters that wash away all sin. Then Bhagiratha went forward on his car and Ganga followed ; and after her came the devas and rishis, asuras, rakshasas, gandharvas and yakshas, kinnaras and nagas and apsaras, and all creatures that inhabit water went along with them. But as Ganga followed Bhagiratha she flooded the sacrificial ground of the puissant Jahna, and he was greatly angered, and in his wrath he drank up all her wondrous waters. Then the deities besought and

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 321

prayed him to set her free, till he relented and released her through his ears, and again she followed Bhagiratha's car. At last she came to the mighty river Ocean and plunged into the nether regions ; there she laved the heap of ashes, and the sixty thousand sons of Sagara were cleansed of every sin and attained to Heaven.

Then Brahma spoke to Bhagiratha. " O most puissant of men," he said, " the sons of Sagara have now gone up to Heaven, and shall endure there so long as Ocean's waters endure on earth. Ganga shall be called thy daughter and receive thy name. Now do thou make offerings of this sacred water for thy ancestors, Sagara and Anshumat and Dilipa, and do thou thyself bathe in these waters and, free from every sin, ascend to Heaven, whither I now repair." " And, O Rama," said Vishvamitra, " I have now related to thee the tale of Ganga. May it be well with thee. He that recites this history wins fame, long life, and Heaven ; he that heareth attains to length of days, and the fulfilment of desires, and the wiping out of every sin."

Manasa Devi

Manasa Devi was the daughter of Shiva by a beautiful mortal woman. She was no favourite of her step mother, Bhagavati, or Parvati, Shiva's wife ; so she took up her abode on earth with another daughter of Shiva, named Neta. Manasa desired to receive the worship due to goddesses; she knew that it would be easy to obtain this if she could once secure the devotion of a very wealthy and powerful merchant-prince of Champaka Nagar, by name Chand Sadagar. For a long time she tried to persuade him ; but he was a stout devotee of Shiva him self, whom he was not going to desert for a goddess of snakes. For Manasa was a goddess and queen of serpents.

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 322

Chand had made a beautiful garden on the outskirts of the city, a veritable earthly paradise, where he was used to eat the air and enjoy the flowers every evening. The first thing Manasa did was to send her snakes to reduce the garden to ashes. But as Chand had received from Shiva himself the magic power of restoring the dead to life, it was an easy matter for him to restore the garden to all its beauty by merely uttering the appropriate charms. Manasa next appeared to Chand in the shape of a beautiful girl, so silvery and radiant that even the moon hid herself behind the clouds when she saw her. Chand fell madly in love with her, but she would not hear a word till he promised to bestow his magic power upon her; and when he did so, she vanished away and appeared in the sky in her own form, and said to Chand : "This is not by chance, nor in the course of nature. But even now worship me, and I will restore your power." But he would not hear of it. Then she destroyed the garden again. But Chand now sent for his friend Shankara, a great magician, who very soon revived the flowers and trees and made the garden as good as before. Then Manasa managed to kill Shankara by guile, and destroyed the garden a third time; and now there was no remedy. Every time one of these misfortunes befell Chand she whispered in his ear : " It is not by chance &c.

Then she sent her serpents to kill every one of his six sons ; at the death of each she whispered the same message in Chand' s ear, saying : " Even now worship me, and all shall be well." Chand was an obstinate man, and sad as he was, he would not give in. On the contrary, he fitted out his ships for a trading voyage and set forth. He was very successful, and was nearing home, with a load of treasure and goods, when a storm fell on the ships.

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 323

Chand at once prayed to Bhagavati, the wife of Shiva, and she protected his ship. Manasa, however, represented to her father that this was not fair. " Is she not content with banishing me from Heaven, but must also interfere with all my doings?" So Shiva persuaded his wife to return to Heaven with him. He began by swearing: "By the heads of your favourite sons, Ganesha and Kartikeya, you must come away at once, Bhagavati, or ......

"Or what? "she said.

" Well, never mind," he replied ; " but, my dear, you should be reasonable. Is it not fair that Manasa should have her own way for once ? After all, she has been very badly neglected, and you can afford to be generous."

So Bhagavati went away with Shiva, the boat sank, and Chand was left in the sea. Manasa had no intention of letting him drown, so she cast her lotus throne into the water. But Manasa had another name, Padma, and this also is the name of the lotus ; so when Chand saw that the floating object by which he was going to save himself was actually padma he left it alone, preferring drowning to receiving any help from a thing bearing the hated name of his enemy. But she whispered : " Even now worship me, and all will be well."

Chand would have been quite willing to die; but this would not suit Manasa at all; she brought him ashore. Behold, he had arrived at the city where an old friend, Chandraketu, had his home. Here he was very kindly treated, and began to recover a little ; but very soon he discovered that Chandraketu was a devotee of Manasa, and that her temple adjoined the house. At once he departed, throwing away even the garments his friend had bestowed upon him.

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 324

He begged some food, and going down to the river, took his bath. But while he was bathing Manasa sent a large mouse, who ate up his rice, so that he had nothing to eat but some raw plantain-skins left by some children on the river-bank. Then he got service in a Brahman family as a reaper and thresher ; but Manasa turned his head so that he worked quite stupidly, and his master sent him off. It was a very long time before he found his way back to Champaka Nagar, and he hated Manasa Devi more than ever.

Now Manasa had two great friends, apsaras of Indra's heaven. They made up their minds to win over the obstinate merchant. One was to be reborn as Chand's son, the other as the daughter of Saha, a mer chant of Nichhani Nagar and an acquaintance of Chand's. When Chand reached home he found his wife had presented him with a beautiful son ; and when the time came for his marriage there was no one so beautiful or so wealthy as Behula, the daughter of Saha. Her face was like an open lotus, her hair fell to her ankles, and the tips of it ended in the fairest curls ; she had the eyes of a deer and the voice of a nightingale, and she could dance better than any dancing girl in the whole city of Champaka Nagar.

Unfortunately, the astrologers predicted that Chand's son, whose name was Lakshmindara, would die of the bite of a snake on the night of his marriage. All this time, of course, the two apsaras had forgotten their divine nature, and only thought themselves ordinary mortals very much in love ; also they were both devoted to the service of Manasa Devi. Chand's wife would not allow the marriage to be postponed, so Chand had to go on with the preparations, though he was quite sure that

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 325

Manasa was going to have her own way in the matter. However, he had a steel house built, taking care that there were no cracks in it large enough for even a pin to enter. The house was guarded by sentinels with drawn swords ; mungooses and peacocks were let loose in the park around it, and every one knows that these creatures are deadly enemies of snakes. Besides this, charms and antidotes and snake-poisons were strewn in every corner. But Manasa appeared to the craftsman who built the house and threatened to kill himself and all his family if he would not make a tiny hole in the steel wall. He was very unwilling to do it, for he said he could not betray his employer ; at last he gave in from sheer fright, and made a hole the size of a hair, hiding the opening with a little powdered charcoal.

Then the marriage day came, and many were the evil omens ; the bridegroom's crown fell off his head, the pole of the marriage pavilion broke, Behula accidentally wiped off the marriage mark from her own forehead after the ceremony as if she had already become a widow.

At last the ceremonies were all over, and Lakshmindara and Behula were left alone in the steel house. Behula hid her face in her hands, and was much too shy to look at her husband, or let him embrace her; and he was so tired by the long fasting and ceremonies of the marriage that he fell asleep. Behula was just as tired, but she sat near the bed and watched, for it seemed to her too good to be true that such a lovely thing as Lakshmindara could be really her husband ; he seemed to her like an enshrined god. Suddenly she saw an opening appear in the steel wall, and a great snake glided in; for some of Manasa's snakes had the power of squeezing themselves into the tiniest space and expanding again at will. But Behula

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 326

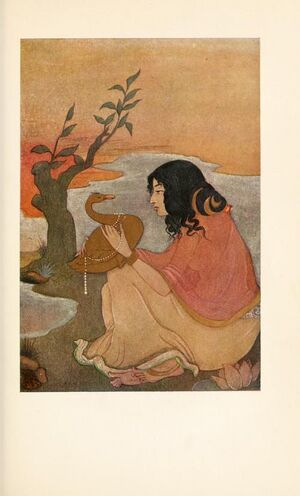

offered the snake some milk, and while it was drinking she slipped a noose over its head and made it fast. The same thing happened with two more snakes. Then Behula grew so heavy she could not keep awake ; she sat on the bed and her eyes closed, opening every now and then with a start to watch the hole in the wall. At last she fell asleep altogether, stretched across Lakshmindara's feet. Then there crept in the serpent Kal-nagim, the same who had destroyed Chand's pleasure-garden, and bit the sleep- ing bridegroom; he cried out to Behula, and she woke just in time to see the snake going out by the hole in the wall.

In the morning Lakshmindara's mother came to the bridal- chamber and found him dead, while Behula lay sobbing by his side. Every one blamed Behula, for they did not believe a snake could have entered the steel house, and accused her of witchcraft; but presently they saw the three snakes tied up, and then they knew that the bride groom had died of snake-bite. But Behula did not attend to what they said, for she was wishing that at least she had not refused her husband's first and last request when she had been too shy to let him embrace her.

It was the custom when anyone died of snake-bite that the body should not be burnt, but set afloat on a raft, in the hope, perhaps, that some skilful physician or snake- charmer might find the body and restore it to life. But when the raft was ready Behula sat down beside the body and said she would not leave it till the body was restored to life. But no one really believed that such a thing could happen, and they thought Behula was quite mad. Every one tried to dissuade her, but she only said to her mother- in-law : " Adored mother, the lamp is still burning in our bridal-chamber. Do not weep any more, but go and close

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 327

the door of the room, and know that as long as the lamp burns I shall still hope that my lord maybe restored to life." So there was no help for it; but Behula floated away, and very soon Champaka Nagar was out of sight. But when she passed by her father's house her five brothers were waiting, and they tried to persuade her to leave the dead body, saying that though she was a widow they wanted to have her back, and they would take every care of her and make her very happy. But she said she could not bear the idea of living without her husband, and she would rather stay even with his dead body than go anywhere else. So she floated away far down the river. It was not very long before the body began to swell and decay; still Behula protected it, and the sight of this inevitable change made her quite unconscious of her own sufferings. She floated past village after village, and every one thought she was mad. She prayed all day to Manasa Devi, and though she did not restore the body to life, still the goddess protected it from storms and crocodiles, and sustained Behula with strength and courage.

Behula was quite resigned ; she felt a more than human power in herself. She seemed to know that so much faith and love could not be in vain. Sometimes she saw visions of devils who tried to frighten her, sometimes she saw visions of angels who tempted her to a life of comfort and safety ; but she sat quite still and indifferent ; she went on praying for the life of her husband.

At last six months went by, and the raft touched ground just where Manasa's friend Neta lived by the river-side. She was washing clothes, but Behula could see by the glory about her head that she was no mortal woman. A beautiful little boy was playing near her and spoiling all her work ; suddenly she caught hold of the child and strangled

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 328

him, and laid the body down beside her and went on with her work. But when the sun set and her work was done, she sprinkled a few drops of water over him, and he woke up and smiled as if he had just been to sleep. Then Behula landed and fell at the washerwoman's feet. Neta carried her up to Heaven to see if the gods might be moved to grant her prayer. They asked her to dance, and she pleased them so much that they promised her to bring her husband back to life and to restore all Chand's losses. But Manasa Devi did not agree to this until Behula under took to convert her father-in-law and persuade him to honour and worship the goddess. Behula promised. Then Behula and Lakshmindara set out on their way home. After a long time they came to her father's house, and they stopped to visit her father and mother. But they would not stay, and set out the same day for Champaka Nagar. She would not go home, however, until she had fulfilled her promise to Manasa Devi. The first people she saw were her own sisters-in-law, who had come to the river- bank to fetch water. She had disguised herself as a poor sweeper, and she had in her hand a beautiful fan on which she had the likeness of every one in the Chand family depicted. She showed the fan to the sisters, and told them her name was Behula, a sweeper-girl, daughter of Saha, a sweeper, and wife of Lakshmindara, son of the sweeper Chand. The sisters ran home to show the fan to their mother, and told her its price was a lac of rupees. Sanaka was very much surprised, but she thought of the lamp in the steel house, and when she ran to the bridal-chamber that had been shut tight for a year, behold the lamp was still burning. Then she ran on to the river-side, and there was her son with Behula. But Behula said : " Dear mother, here is your son ; but we cannot come home till my father-

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 329

in-law agrees to worship Manasa Devi; that is why I

brought you here by a trick."

Chand was not able to resist any longer; Manasa Devi had conquered. He worshipped her on the eleventh day of the waning moon in the very same month. It is true that he offered flowers with his left hand, and turned away his face from the image of Manasa ; but, for all that, she was satisfied, and bestowed on him wealth and prosperity and happiness, and she restored his friend Shankara to life. Ever since then Manasa Devi's claim to the worship of mortals has been freely admitted.

Note on Manasa Devi

This legend of Manasa Devi, the goddess of snakes, who must be as old as the Mykenean stratum in Asiatic culture, reflects the conflict between the religion of Shiva and that of feminine local deities in Bengal. Afterwards Manasa or Padma was recognized as a form of Shakti (does it not say in the Mahabharata that all that is feminine is a part of Uma ?), and her worship accepted by the Shaivas. She is a phase of the mother-divinity who for so many wor shippers is nearer and dearer than the far-off and in personal Shiva, though even he, in these popular legends, is treated as one of the Olympians with quite a human character.

"In the month of Shravana [July- August]," writes Babu Dinesh Chandra Sen, "the villages of Lower Bengal present a unique scene. This is the time when Manasa Devi is worshipped. Hundreds of men in Sylhet, Backergunge, and other districts throng to the river-side to recite the songs of Behula. The vigorous boat-races attending the festivity and the enthusiasm that charac terizes the recitation of these songs cannot but strike an

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 330

observer with an idea of their vast influence over the masses. There are sometimes a hundred oars in each of the long narrow boats, the rowers singing in loud chorus as they pull them with all their might. The boats move with the speed of an arrow, even flying past the river steamers. These festivities of Manasa Puja sometimes occupy a whole month . . . how widespread is the popularity of these songs in Bengal may be imagined from the fact that the birthplace of Chand Sadagar is claimed by no less than nine districts " and by the fact that the Manasa Mangal, or Story of Manasa, has been told in as many as sixty versions by poets whose names are known, dating from the twelfth century onward to the present day. " It must be remembered," adds Dinesh Babu, "that in a country where women commonly courted death on their husband's funeral pyre this story of Behula may be regarded as the poet s natural tribute at the feet of their ideal."

The Elephant and Crocodile

There dwelt a royal elephant on the slopes of Triple Peak, wandered through the forests with his herd of wives. Fevered with the juice exuding from his temples, he plunged one day into a lake to quench his thirst ; after drinking deep, he took water in his trunk and gave it to his wives and children. But just then an angry crocodile attacked him, and the two struggled for an endless time, each striving to draw the other toward himself. Piteously the elephants trumpeted from the bank, but they could not help. At last the royal elephant grew weak, but the crocodile was not yet weary, for he was at home in his own element.

Then the royal elephant prayed ardently and with devotion

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 331

to the Adorable, the Supreme Being; at once came Vishnu, seated upon Garuda, attended by the devas. He drew forth the crocodile and severed its neck with a cast of his discus, and so saved the royal elephant. This was the working out of an old curse ; the elephant was a gandharva who in another life had cursed a rishi who disturbed him at play. That rishi was the crocodile. By another rishi's curse the gandharva had become an elephant.

The elephant of the story stands for the typical human soul of our age, excited by desires ; given over too much to sensual pleasure, the demon would have carried him away, he knew not where. There was no salvation for him until he called on Vishnu, who speedily saves all those who call upon him with devotion.

Nachiketas and Yama

There was a cowherd of the name of Vajashrava; desiring a gift from the gods, he made offerings of all he owned. But the kine he had were old, yielding no milk and worthless; not such as might buy the worshipper a place in Heaven. Vajashrava had a son; he would have his father make a worthier offering. To his sire he spoke: "To which god wilt thou offer me?" "To Death I give thee."

Nachiketas thought : " I shall be neither the first nor last that fares to Yama. Yet what will he do with me? It shall be with me as with others; like grass a man decays, like grass he springeth up again." So Nachiketas went his way to Death's wide home, and waited there three days ; for Death was on a journey. When Death returned his servants said : " A Brahman guest burns like a fire ; Nachiketas waits three days unwelcomed ; do thou

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 332

soothe him with an offering of water, for all is lost to him in whose abode a Brahman waits unfed."

Then Death spake to Nachiketas: "Since thou, an honoured guest, hast waited in my house three days unfed, ask of me three boons in return, and I shall grant them." Then first he prayed : " Grant to my father peace and to know and welcome me when I return." Death answered : " Be it so."

Nachiketas asked again: "In Heaven-world the folk are quit of thee ; there is neither hunger, nor eld, nor fear of death. Reveal to me the sacred fire that leads to Heaven." Then Death described the sacred fire what stones for its altar, and how disposed ; and Nachiketas said it over, learning the lesson taught by Death. Death spoke again : " I grant thee, furthermore, that this sacred fire be known for ever by thy name ; thine is the fire that leads to Heaven, thy second boon."

Nachiketas asked again: "The great mystery of what cometh after death; he is, some say; others say, he is no more. This great doubt I ask thee to resolve." Death replied: "Even the gods of old knew not this; this is a matter hard to be learnt; ask me, O Nachiketas, any other boon, though it be a hundred sons, or untold wealth, or broad lands, or length of days. All that a man can desire shall be thine, kingship, wealth, the fairest song stresses of Indra's heaven; only ask not of death."

Nachiketas answered: "These be matters of a day and destroy the fiery energy of men; thine be the wealth, thine the dance and song. What avails wealth whenas thou dost appear? How shall a man delight in life, however long, when he has beheld the bliss of those who perish not? This doubt of the Great Hereafter I ask thee to resolve; no other boon I ask."

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 333

Death replied: "Duty is one, delight another; these twain draw a man in diverse paths. Well is it for him that chooses duty; he goes astray who seeks delight. These twain, wisdom and folly, point to diverse ends. Well has Nachiketas spoken, seeking wisdom, not goaded by desires. Even the learned abide in delusion, blind led by the blind; while to the fool is naught revealed. This world, and no other, he thinketh; and so cometh again and again into my power.

" But he is great who tells of the One, of whom the many may never hear, whom the many, though they hear, may not know; a marvel is he who knoweth the Brahman. Untold is he, no path leads to him.

" Having heard and well grasped him with insight, attaining to that subtle One, a mortal is gladdened and rejoices for good cause. Wide is the gate for Nachiketas, methinks."

Nachiketas answered :

" Other than good, other than evil, other than formless or than forms, other than past or future declare thou That."

Death resumed:

" That goal of sacred wisdom, of goodly works and faith, is Om This word is Brahman, the supreme. He who doth comprehend this word, whatsoever he desires is his. " For that Singer is not born, nor does he ever die. He came not any whence, nor anything was he. Unborn, eternal, everlasting, ancient ; unslain is he, though the body be slain. " If the slayer thinks he slays, or the slain deems he is slain, they err; That neither slayeth nor is slain.

" Smaller than small, greater than great, that Self indwells in every creature s heart.

"Sitting, he travels far; lying, he speedeth everywhere; who knoweth him hath no more grief.

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 334

"This Self is not obtainable by explanation, nor by intellection, nor by much hearkening to scripture; whom he chooses, to him That is revealed. But he that knoweth that all things are Self, for him what grief, what delusion lingers, knowing all things are That One? "When all desires that linger in the heart are driven forth, then mortal is made immortal, he becometh Brahman.

"When every knot of the heart is loose then doth he win immortal Being. Thus far the teaching." Thus having learnt the wisdom taught by Death, and finding Brahman, Nachiketas was freed from death. So verily shall he be free who knoweth that Supreme Self.

The Story of Kacha and Dewayani

Many were the battles of old between the gods and demons, for each desired the sovereignty and full possession of the three worlds. The devas appointed Brihaspati as their priest, master of sacrificial rites ; the asuras, Ushanas. Between these two great Brahmans there was fierce rivalry, for all those demons that were slain in battle with the gods were brought to life by Ushanas, and fought again another day. Many also were the gods slain by the demons ; but Brihaspati knew not the science of bringing to life as Ushanas knew it, therefore the gods were greatly grieved. They went, therefore, to Brihaspati's son Kacha and asked him to render them a great service, to become the disciple of Ushanas and learn the secret of bringing to life. "Then shalt thou share with us in the sacrificial offerings. Thou mayst easily do this, since thou art younger than Ushanas, and it is therefore meet that thou shouldst serve him. Thou mayst also serve his daughter DevayanI, and win the favour of

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 335

both. From Devayani thou shall surely win that know- ledge," said they. " So be it," answered Kacha, and went his way.

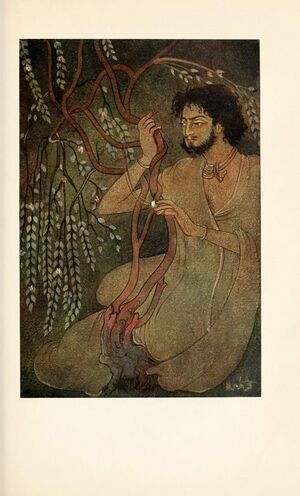

To Ushanas he said: "Receive me as thy disciple. I am the son of Brihaspati, and my name is Kacha. Be thou my master, and I shall practise restraint for a thousand years." Ushanas welcomed him, and the vow was made. Then Kacha began to win the favour of Ushanas and Devayani. He was young, and sang and played on divers instruments; and she, who was also young, was not hard to please. He gave her flowers and fruits and did her service. She, too, with songs and pleasant manners served him. Thus passed five hundred years, half of the time appointed in the vow.

Then Kacha's purpose became known to the demons, and they slew him in wrath in a lonely part of the forest, where he was tending his master's cows. They cut his body in many pieces and gave it to the wolves and jackals. When twilight came the cows returned to the fold alone. Then Devayani said to her father: "The sun has set, the evening fire is lit, the cattle have returned alone. Kacha has not come; he is either lost or dead. And, O father, I will not live without him." Then Ushanas said : I will bring him to life by saying: Let him come," and summoned him. At once Kacha appeared before his master, tearing the bodies of the wolves that had devoured him. When Devayani asked him what had hindered his return, he answered that the asuras had fallen upon him in the forest and given his body to the wolves and jackals; "but brought to life by the summons of Ushanas, I stand before you none the less."

Again it befell that Kacha was in the forest, see flowers desired by Devayani, and the demons found hini

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 336

and slew him, and grinding his body into paste, they mixed it with the waters of the ocean. As before, Devayani told her father that Kacha had not returned, and Ushanas summoned him, so that he appeared whole and related all that had befallen.

A third time he was slain, and the asuras burnt his flesh and bones to ashes and mixed the ashes with the wine that Ushanas drank, for in those days the Brahmans yet drank wine. Then Devayani said to her father again: "O father, Kacha has gone to gather flowers, but he comes not back. Surely he is lost or dead. I will not live without him!" Ushanas answered: "O my daughter, surely Brihaspati's son has gone to the realm of the dead. But what may I do, for though I bring him back to life, he is slain again and again? O Devayani, do not grieve, do not cry. Thou shouldst not sorrow for a mortal, for thou art daily worshipped by the gods." But Devayani answered: "Why should I not grieve for the son of Brihaspati, who is an ocean of ascetic virtue ? Kacha was the son and grandson of a rishi. He, too, kept the rule of self-restraint, and was ever alert and skilful. I will starve and follow him. Fair was Kacha and dear to me."

Then Ushanas was grieved and cried out against the asuras, who slew a disciple under his protection ; and at Devayani's prayer he began to summon Kacha back from the jaws of death. But he answered feebly from within his master s stomach: " Be gentle unto me, O master; I am Kacha that serveth thee. Consider me as thine own son." Ushanas said : " How, O Brahman, earnest thou into my stomach ? Forsooth, I shall desert the asuras and join the gods ! " Kacha answered : " Memory is mine and all the virtue of my discipline, but I suffer intolerable pain.

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 337

Slain by the asuras and burnt to ashes, I was mixed with thy wine."

Then Ushanas said to Devayani : " What can I do for thee, for it is by my death that Kacha can have back his life ? He is within me, and may not come forth without the tearing of my stomach". She answered : " Either evil is alike to me. If Kacha dies, I will not live ; and if thou die, I also die." Then Ushanas said to Kacha: " Success is thine, since Devayani looks on thee so kindly. Receive, therefore, from me the lore of Bringing-to-life, and when thou comest forth from me thou shalt restore my life in turn." Then Kacha came forth from the master's stomach like the full moon in the evening; and seeing his teacher lying lifeless, he revived him by the science he had received and worshipped him, calling him father and mother as the giver of knowledge. Thereafter Ushanas decreed that no Brahman ever should drink wine. Also he summoned the asuras, and announced to them : " Ye foolish demons, know that Kacha has attained his will. Henceforth he shall dwell with me. He who has learnt the science of Bringing-to-life is even as Brahman himself." The demons were astonished, and departed to their homes; but Kacha stayed with the master for a thousand years until the time came for him to return to the gods. He received permission from Ushanas to depart ; but Devayani, seeing him about to go, said to him : " Hear me ; remember my affection to thee during thy vow of self-restraint; now the time thereof is ended, do thou set thy love on me and take my hand according to the sacred rites." But Kacha answered : " Behold, I honour thee as much as, nay more than, even thy father ; dearer than life thou art, my master s daughter. Yet thou shouldst not say these words to me." She answered again :

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 338

"Thou art likewise my father' s teacher's son, and I must honour thee. Recollect my affection when the asuras had slain thee. I am altogether thine ; do not abandon me with out a fault." Kacha replied : " Tempt me not to sin ; be gentle unto me, thou of fair brows. Where thou hast been in the body of the sage, there have I also been : thou art my sister. Therefore speak not thus. Happy days we have spent together, thou slender-waisted ; grant me leave to go to my home now, and thy blessing that my journey may be safe. Think of me as one who would not sin." Then Devayani cursed him : " Since thou refusest me, thy knowledge shall be fruitless."

Kacha answered : " I have refused thee only because thou art my master's daughter and my sister, not for any fault. Curse me if thou must, though I deserve it not. But thou speakest from passion, not for duty's sake, and thy wish shall fail. Behold also, no rishi's son shall wed with thee. Thou sayest that my knowledge shall bear no fruit; be it so, but in him it shall bear fruit to whom I shall impart it." Then Kacha took his way to the dwellings of the gods and was greeted by Indra, who honoured him, saying : " Great is the boon thou hast achieved for us ; be thou hereafter a sharer in the sacrificial offerings : thy fame shall never die."

Thus far the tale of Kacha and Devayani.

Note on Kacha and Devayani

Even the planets must sooner or later have shared in the general process of the spiritualizing of stellar myths, and a significant instance seems to be the story of Devayani and Kacha, from the opening volume of the Mahabharata. Here it would appear that we have a very ancient fragment, for as a poetic episode the story stands loosely

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 339

connected with an archaic genealogical relation not unlike the Semitic account of Sara and Hagar in which appear mixed marriages between Brahmans and Kshatriyas, polygamy, and the matriarchal custom and ideal of proposals made by a woman held binding upon the man. All these features of the legend are felt by the final editor to be highly anomalous, and time and words are in- artistically spent in arguments for their justification by the characters involved. But this is a very common feature in the dressing-up of old tales to take a place in new productions, and the arguments only confirm the perfect naturalness of the incidents when first related. How Devayani, the daughter of the planet Shukra, 1 of Brahman rank, became the ancestress of certain royal or asura princes and tribes, and how the king whom she wedded was also the progenitor of three other purely asura races, or dynasties these things may have been the treasured pedigrees of families and clans. From a national point of view it may have been binding on the annalist to include them in every version of the epic chronicles. As a poet, however, the point that interested the last editor of the Mahabharata was a matter that also interests us a romance that occurred to Devayani in her youth, and stamped her as a daughter of the planetary order, though wedded to a king.

The mythos comes down from that age when there were constant struggles for supremacy between the gods (devas) and the demons (asuras). Who were these asuras ? Were they long-established inhabitants of India, or were they new invaders from the North-West? They are not classed with the aboriginal tribes, it is to be marked, or

1 i.e., Venus, masculine in Hindu astrology. Also named Ushanas, as above.

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 340

referred to as Dasyus or slaves. There still remain in the country certain ancient metal-working communities who may represent these asuras in blood, as they certainly do in name. And the name of Assyria is an abiding witness to the possibility of their alien origin. In any case it would appear as an accepted fact, from the story of Devayani, that the asuras were proficients in magic. It is told that they obtained a Brahman to act as their sacrificial priest, who was in some vague way an embodiment of Shukra, the planet Venus. The gods, on the other hand meaning perhaps the Aryans, who were Sanskrit-speaking were served in the same capacity by a Brahman representing the influence and power of Brihaspati, or Jupiter. The planetary allusions in these names are confirmed by the reproachful statement of the gods that "Shukra always protects the asuras, and never protects us, their opponents." No one could grumble that the archbishop of a rival people did not protect them. But the complaint that a divinity worshipped by both sides shed protecting influences on one alone is not unreasonable. What were the original fragments from which this story was drawn ? Was the whole thing a genealogical record, on the inclusion of which in a national history certain tribes and clans had a right to insist? And is the whole incident of Devayani and Kacha a sheer invention of the latest editor to explain what had in his time become the anomalous tradition of the marriage of Devayani, daughter of a Brahman, to Yayati, of the royal caste ? It may be so. And yet as against this we have that statement, so like a genuine echo from the past, that " there were in former times frequent contests between gods and demons for the possession of the whole Three Worlds." In bringing about the highly dovetailed condition of the

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 341

story as it now stands we may be sure that the latest poet has had a large hand, but in all probability the parts themselves, even to this romance of Kacha and Devayani, are now as they were in long-inherited lore.

The latest poet feels his own sentiment as much outraged as our own by the unwomanly insistence of Devayani on the acceptance of her hand by Kacha. But, as a matter of fact, the tale probably came down to him, as to us, from the age of the Matriarchate, when it was the proper thing for a man to become a member of his wife's kindred ; and Devayani, in the first inception of her romance, may not have striven to make Kacha her husband so much as to pledge him to remain amongst the asuras. Even in this she was prompted, we may suppose, more by the desire of preserving the magical knowledge of her people from betrayal than by personal motives. And Kacha, similarly, whatever he may urge, in the hands of his latest narrator, as the reason of his refusal, was really moved, in the earliest version, by the idea that this is the last and supreme temptation that confronts his mission. His one duty is, in his own eyes, to fulfil the task as he undertook it in his youth, namely, to leave the demons and return to the gods to impart to them the knowledge they sent him out to win. And finally, the story in this its completed presentment bears more than a trace of that poetizing of the planetary influences of which the ancient art ot astrology may be regarded as the perfected blossom and fruit.

Pururavas and Urvashi

There was a king by name Pururavas. Hunting one day in the Himalayas, he heard a cry for help ; two apsaras had been carried off by rakshasas from a pleasure-party in the flowery woods. Pururavas pursued and rescued them ; they

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 342

were Urvashi and her friend Chitralekha. He prayed Urvashi for her love ; she granted it, with this condition : "Thou shalt not let me see thee naked."

Long she dwelt with him, and time came when she would be a mother. But the gandharvas, who are the friends and companions of the apsaras, missed their fellow, and they said together: " It is long, indeed, that Urvashi dwells with men; find out a way to bring her back." They were agreed upon a way to bring her back. She had a ewe with two small lambs, dear pets of hers, tied to her bed. While yet Pururavas lay beside his darling the gandharvas carried off a lamb. " Alas ! " she cried, " they have carried off my pet as though no hero and no man was with me." Then they carried off the second, and Urvashi made the same complaint.

Pururavas thought : " How can that be a place without a hero and without a man where I am found ? " Naked, he sprang up in chase ; too long he thought it needed to put on a garment. Then the gandharvas filled the sky with lightning and Urvashi saw him, clear as day; and, indeed, at once she vanished.

The sorry king wandered all over Hindustan wailing for his darling. At last he reached a lake called Anyata-plaksha. There he saw a flock of swans ; they were the apsaras, with Urvashi, but Pururavas did not know them. She said : " There is he with whom I dwelt." The apsaras said together: "Let us reveal ourselves," and, "So be it," they said again. Then Pururavas saw Urvashi and prayed her sorely: "O dear wife, stay and hear me. Unspoken secrets that are yours and mine shall yield no joy; stay then, and let us talk together." But Urvashi answered : "What have I to do to speak with thee ? I have departed like the first of dawns. Go home

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 343

again, Pururavas. I am like the very wind and hard to bind. Thou didst break the covenant between us ; go to thy home again, for I am hard to win."

Then Pururavas grieved and cried : " Then shall thy friend and fellow rush away this day, upon the farthest journey bent, never returning ; death will he seek, and the fierce wolves shall have him."

Urvashi answered : " Do not die, Pururavas ; do not rush away ! Let not the cruel wolves devour thee ! Take it not to heart, for lo ! there may not be friendship with any woman ; women's hearts are as hyenas . Go to thy home again." But a memory came into her mind of her life with him, and a little she relented ; she said to Pururavas : " Come, then, on the last night of the year from now ; then shalt thou stay with me one night, and by then, too, this son of thine shall have been born." Pururavas sought her on the last night of the year : there was a golden palace, and the gandharvas cried him, "Enter," and they sent Urvashi to him. She said: " When morning dawns the gandharvas will offer thee a boon, and thou must make thy choice." "Choose thou for me," he said, and she replied : " Say, Let me be one of your very selves. "

When morning came, " Let me be one of your very selves," he said. But they answered : " Forsooth the sacred fire burns not upon earth which could make a man as one of us." They gave him fire in a dish and said : " Sacrifice therewith, and thou shalt become a gandharva like ourselves." He took the fire, and took his son, and went his way. He set down the fire in the forest, and went with the boy to his own home. When he returned, " Here am I back," he said ; but lo ! the fire had vanished. What had been the fire was an Asvattha tree; and what the dish, a Shami

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 344

tree. Then he sought the gandharvas again. They counselled him : " Make fire with an upper stick of the Asvattha tree, and a lower stick of the Shami ; the fire thereof shall be the very fire thou didst receive from us." Then Pururavas made fire with sticks of the Asvattha and the Shami, and making offerings therewith, he was made one of the gandharvas and dwelt with Urvashi evermore.

Story of Savitri and Satyavan

Yudhishthira questioned Markandeya if he had ever seen or heard of any noble lady like to Draupadi's daughter.

Markandeya answered :

There was a king named Lord-of-Horses ; he was virtuous, generous, brave, and well-beloved. It grieved him much that he had no child. Therefore he observed hard vows and followed the rule of hermits. For eighteen years he made daily offerings to Fire, recited mantras in praise of Savitri, and ate a frugal meal at the sixth hour. Then at last Savitri was pleased and revealed herself to him in visible form within the sacrificial fire. "I am well pleased," she said, "with thy asceticism, thy well-kept vows, thy veneration. Ask, great king, whatever boon thou wilt." " Goddess," said the king, " may sons be born to me worthy of my race, for the Brahmans tell me much merit lies in children. If thou art pleased with me, I ask this boon." Savitri replied : "O king, knowing thy wish, I have spoken already with Brahma that thou shouldst have sons. Through his favour there shall be born to thee a glorious daughter. Thou shouldst not answer again : this is the grandsire's gift, who is well pleased with thy devotion." The king bowed down and prayed. "So be it," he said, and Savitri

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 345

vanished. It was not long before his queen bore him a shining girl with lotus eyes. Forasmuch as she was the gift of the goddess Savitri, the wife of Brahma, she was named Savitri with all due ceremony, and she grew in grace and loveliness like unto Shri herself. Like a golden image the people thought her, saying : " A goddess has come amongst us." But none dared wed that lady of the lotus eyes, for the radiant splendour and the ardent spirit that were in her daunted every suitor.

One holiday, after her service of the gods, she came before her father with an offering of flowers. She touched his feet, and stood at his side with folded hands. Then the king was sad, seeing his daughter of marriageable age and yet unwooed. He said to her: " My daughter, the time for thy bestowal has come; yet none seek thee. Do thou, therefore, choose for thyself a husband who shall be thy equal. Choose whom thou wilt ; I shall reflect and give thee unto him, for a father that giveth not his daughter is disgraced. Act thou therefore so that we may not meet with the censure of the gods."

Then Savitri meekly bowed to her father's feet and went forth with her attendants. Mounting a royal car she visited the forest hermitages of the sages. Worshipping the feet of those revered saints, she roamed through all the forests till she found her lord.

One day when her father sat in open court, conversing with the counsellors, Savitri returned, and, seeing her father seated beside the rishi Narada, bowed to his feet and greeted him. Then Narada said: "Why dost thou delay to wed thy girl, who is of marriageable age ? " The king replied : " It was for this that she went forth, and even now she returns. Hear whom she has chosen for her

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 346

husband." So saying, he turned to Savitri, commanding her to relate all that had befallen her.

Standing with folded hands before the king and sage, she answered : " There was a virtuous king of the Shalwas, Dyumatsena by name. He grew blind ; then an ancient foe wrested the kingdom from his hands, and he, with his wife and little child, went forth into the woods, where he practised the austerities appropriate to the hermit life. The child, his son, grew up in that forest hermitage. He is worthy to be my husband ; him have I accepted in my heart as lord."

Then Narada exclaimed : Greatly amiss has Savitri done in taking tor her lord this boy, whose name is Satyavan ; albeit I know him well, and he excels in all good qualities. Even as a child he took delight in horses and would model them in clay or draw their pictures; wherefore he has been named Horse-painter."

The king asked : " Has this Prince Satyavan intelligence, forgiveness, courage, energy?" Narada replied: "In energy he is like the sun, in wisdom like Brihaspati, brave like the king of gods, forgiving as the earth her self. Eke he is liberal, truthful, and fair to look upon ? " Then the king inquired again : " Tell me now what are his faults." Narada answered : " He hath one defect that overwhelms all his virtues, and that fault is irremediable. It is fated that he will die within a year." Then the king addressed his daughter : " Do thou, O Savitri, fair girl, choose for thyself another lord ; for thou hast heard the words of Narada." But Savitri answered : " The die can fall but once ; a daughter can only once be given away ; once only may it be said : I give away ! Forsooth, be life short or long, be he virtuous or vicious, I have chosen my husband once for all. I shall not

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 347

choose twice. A thing is first thought of in the heart, then it is spoken, then it is done ; my mind is witness thereof." Then Narada said to the king : " Thy daughter's heart is unwavering ; she may not be turned from the right way. Moreover, none excelleth Satyavan in virtue ; the marriage has my approval." The king, with folded hands, answered again : " Whatsoever thou dost command is to be done." Narada said again : " May peace attend the gift of Savitri. I shall now go on my ways ; be it well with all " ; and therewith he ascended again to Heaven.

On an auspicious day King Lord-of- Horses (Ashwapati) with Savitri fared to the hermitage of Dyumatsena. Entering on foot, he found the royal sage seated in contemplation beneath a noble tree ; him the king reverenced duly, with presents meet for holy men, and announced the purpose of his visit. Dyumatsena answered : " But how may thy daughter, delicately nurtured, lead this hard forest life with us, practising austerity and following the rule of hermits?" The king replied: "Thou shouldst not speak such words to us ; for my daughter knoweth, like myself, that happiness and sorrow come and go, and neither endures. Thou shouldst not disregard my offer." It was arranged accordingly, and in the presence of the twice-born sages of the forest hermitages Savitri was given to Satyavan. When her father had departed she laid aside her jewels and garbed herself in bark and brown. She delighted all by her gentleness and self- denial, her generosity and sweet speech. But the words of Narada were ever present in her mind.

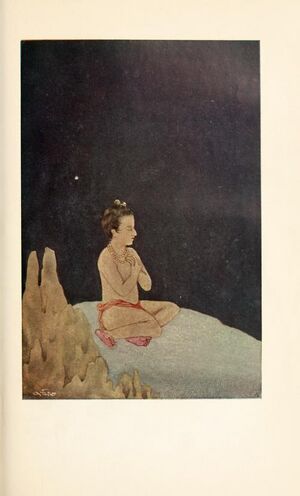

At length the hour appointed for the death of Satyavan approached; when he had but four days more to live Savitri fasted day and night, observing the penance of "Three Nights." By the third day Savitri was faint and

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 348

weak, and she spent the last unhappy night in miserable reflections on her husband s coming death. In the morning she fulfilled the usual rites, and came to stand before the Brahmans and her husband's father and mother, and they for her helping prayed that she might never be a widow.

Satyavan went out into the woods with axe in hand, suspecting nothing, to bring home wood for the sacrificial fire. Savitri prayed to go with him, and he consented, if his parents] also permitted it. She prayed them sweetly to allow it, saying that she could not bear to stay behind and that she desired exceedingly to see the blossoming trees. Dyumatsena gave her leave, saying : " Since Savitri was given by her father to be my daughter-in-law I cannot remember that she has asked for anything at all. Now, therefore, let her prayer be granted. But do not," he added, " hinder Satyavan's sacred labour."

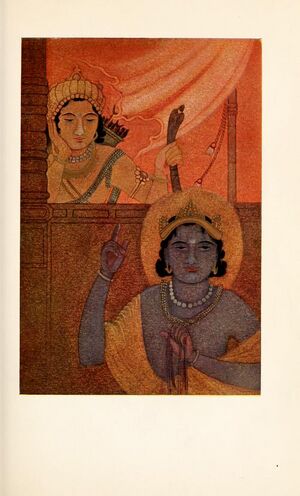

So Savitri departed with her lord, seeming to smile, but heavy-hearted ; for, remembering Narada's words, she pictured him already dead. With half her heart she mourned, expectant of his end ; with half she answered him with smiles, as they passed beside the sacred streams and goodly trees. Presently he fell to work, and as he hewed at the branches of a mighty tree he grew sick and faint, and came to his wife complaining that his head was racked with darting pains and that he would sleep awhile. Savitri sat on the ground and laid his head upon her lap; that was the appointed time of Satyavan s death. Immediately Savitri beheld a shining ruddy deity, dark and red of eye and terrible to look upon ; he bore a noose in his hand. He stood anH gazed at Satyavan. Then Savitri rose and asked him humbly who he might be and what he sought to do. " I am Yama, Lord of Death,"

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 349

he answered, "and I have come for Satyavan, whose

appointed span of life is ended." So saying, Yama drew

forth the soul from Satyavan's body, bound in the noose,

and altogether helpless; therewith he departed toward

the south, leaving the body cold and lifeless.

Savitri followed close ; but Yama said : " Desist, O Savitri. Return, perform thy husband's funeral rites. Thou mayst come no farther." But she answered : " Whither my lord is brought or goeth of his own will I shall follow ; this is the lasting law. The way is open to me because of my obedience and virtue. Lo, the wise have said that friendship is seven-paced. Relying on friendship thus contracted, I shall say thee somewhat more. Thou dost order me to follow another rule than that of wife; thou wouldst make of me a widow, follow ing not the domestic rule. But the four rules are for those who have not attained their purpose, true religious merit. It is otherwise with me ; for I have reached the truth by fulfilment of the duty of a wife alone. It needs not to make of me a widow." Yama replied : " Thou sayest well, and well thou pleasest me. Ask now a boon, whatsoever thou wilt, except thy husband's life." She prayed that Dyumatsena should regain his sight and health, and Yama granted it. Still Savitri would not return, saying that she would follow still her lord, and, besides, that friendship with the virtuous must ever bear good fruit. Yama admitted the truth of this, and granted her another boon ; she asked that her father should regain his kingdom. Yama gave his promise that it should be accomplished, and commanded Savitri to return. Still she refused, and spoke of the duty of the great and good to protect and aid all those who seek their help. Yama then granted her a third boon, that her father should have

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 350

a hundred sons. Still Savitri persisted. "Thou art called the Lord of Justice," she said, " and men ever trust the righteous ; for it is goodness of heart alone that inspireth the confidence of every creature." When Yama granted another boon, save and except the life of Satyavan, Savitri prayed for a hundred sons born of herself and Satyavan. Yama replied: "Thou shalt, O lady, obtain a hundred sons, renowned and mighty, giving thee great delight. But thou hast come too far ; now I pray thee to return." But she again praised the righteous. " It is the righteous," she said, "who support the earth by their austere life; they protect all." Again Yama was pro pitiated by Savitri's edifying words, and he granted another boon. But now Savitri answered : " O giver of honour, what thou hast already granted cannot come to pass without union with my husband ; therefore I ask his life together with the other boons. Without him I am but dead, without him I do not even desire happiness. Thou hast given a hundred sons, and yet dost take away my lord, without whom I may not live. I ask his life, that thy words may be accomplished."

Then Yama yielded and gave back Satyavan, promising him prosperity and a life of four centuries, and descend ants who should all be kings. Granting all that Savitri asked, the lord of the ancestors went his way. Then Savitri returned to Satyavan's body, and she lifted his head upon her lap; behold, he came to life, like one returning home from sojourn in a strange land. " I have slept overlong," he said ; " why didst thou not awake me ? Where is that dark being who would have carried me away?" Savitri answered : "Thou hast slept long. Yama has gone his way. Thou art recovered; rise, if thou canst, for night is falling."

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 351

Then those two returned, walking through heavy night along the forest paths.

Meanwhile Dyumatsena and his wife and all the sages remained in grief. Yet the Brahmans were of good hope, for they deemed that Savitri's virtue must avail even against fate, and they gave words of comfort to the king. Moreover, Dyumatsena suddenly regained his sight, and all took this for an omen of good fortune, betokening the safety of Satyavan. Then Savitri and Satyavan returned through the dark night, and found the Brahmans and the king seated beside the fire. Warm was their welcome and keen the questioning; then Savitri related all that had befallen, and all saluted her; then, forasmuch as it was late, all went to their own abodes.

Next day at dawn there came ambassadors from Shalwa to say that the usurper had been slain, and the people invited Dyumatsena to return and be again their king. So he returned to Shalwa and lived long; and he had a hundred sons. Savitri and Satyavan had also the hundred sons bestowed by Yama. Thus did Savitri by her goodness alone raise from a poor estate to the highest fortune herself, her parents, and her lord, and all those descended from them.

"And," said Markandeya to Yudhishthira -even so shall Draupadi save all the Pandavas."

Shakuntala

This old story, best known to English readers in translations of Kalidasa's play, is an episode of the Mahabharata, giving an account of Bharata himself, the ancestor of the warring princes of the great epic, from whom, also, the; name of India, " Bharatvarsha," is derived. The story of Shakuntala given here is taken almost literally from the

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 352

Javanese version lately published by D. Van Hinloopen Labberton a version superior in directness and simplicity to that of the Sanskrit Mahabharata, and as a story (not of course as a play) superior to Kalidasa's :

There was a raja, Dushyanta, whose empire extended to the shores of the four seas. Nothing wrong was done in his reign ; goodness prevailed, because of his example. One day he was hunting in the Himalayan forests, and went ever deeper and deeper into the woods; there he came upon a hermitage, with a garden of fair flowers and every sort of fruits, and a stream of clear water. There were animals of every kind ; even the lions and tigers were well disposed, for the peaceful mind of the hermit constrained them. Birds were singing on every bough, and the cries of monkeys and bears rang like a recitation of Vedic prayers, delighting the king's heart. He ordered his followers to remain behind, for he desired to visit the hermit without disturbing his peaceful retreat. The garden was empty ; but when he looked into the house he saw a beautiful girl, like an apsara upon earth. She bade him welcome and offered him water to wash his feet and rinse his mouth, in accordance with the custom for guests. The king asked her whose was the hermitage and why it was empty. She answered : " By leave of your highness, it is the hermitage of the sage Kanva. He has gone out to gather fuel for the sacrificial fire; please, Maharaja, wait here till he returns, as he will very soon come." While the maiden was speaking the king was struck with love of her. But he answered with a question. " Pardon, fair mother," he said ; " I have heard of the saintly Kanva. But it is said that he has naught to do with women ; in what relation do you stand to him?" The hermit-maiden replied: "By leave of your highness, he is my father;

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 353

and as to the way in which that came to pass, here is a Brahman guest who may inform you; please ask him regarding the story of my birth."

The Brahman related the story of the girl's birth. The great yogi Vishvamitra was once a king ; but he renounced his royal estate, desiring to attain the same spiritual dignity as Vashishtha. He practised such severe penance that Indra himself feared that his kingdom would be taken from him. So he called one of the most beautiful of the dancers in heaven, Menaka, the pearl of the apsaras, and dispatched her to tempt the holy man. She accepted the mission, after reminding Indra that Vishvamitra was a man of immense occult powers, able at his will to destroy the Three Worlds ; to which he replied by sending with her the gods Wind and Desire. She went to the hermitage and disported herself in an innocent manner, and just when Vishvamitra glanced toward her the Wind came by and revealed her loveliness, and at the same time the god of Desire loosed his arrow and struck him to the heart, so that Vishvamitra loved the apsara. When she found herself with child she thought her work was done; she might return to Heaven, she thought. Away she went along the river Malini and up into the Himalayas; there she bore a girl, and left the child alone, guarded by the birds, and came again to Indra. Kanva found the child, attended only by shakuni birds; therefore he named her Shakuntala. " This Shakuntala," said the young Brahman guest, " is the same hermit-maiden that gave your high ness welcome."

Dushyanta spoke again to the girl: "Well born thou art," he said, " daughter of an apsara and of a great sage ; do thou, fair one, become my bride, by the rite of mutual consent." But she would not, wishing to wait till Kanva

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 354

came ; only when the king urged her overmuch she gave consent, upon the condition that her son should be the heir-apparent and succeed to the throne. The king agreed, and he and she were bound by the gandharva rite of mutual consent. Then the king departed to his city, saying he would send for Shakuntala without delay. Soon Kanva came, but Shakuntala could not meet him for her shyness ; but he knew all that had befallen and came to her, and said she had done well, and foretold that she would bear an emperor. After long months she bore a perfect child, a fair boy, and Kanva performed the Kshatriya rite for him. While he grew up he was ever with the hermit, and shared a little of his power, so that he was able to subdue every wild beast, even lions and tigers and elephants, and he won the name of All- tamer. He bore the birth-marks of an emperor.

But all this time no message came from King Dushyanta. Then Kanva sent Shakuntala with the child in charge of hermits to the court ; she came before the king as he was giving audience, and asked him to proclaim the child his heir-apparent. He replied : " I never wedded thee, O shameless hermit-girl ! Never have I seen thy face before. Dost think there are no fair girls in the city, then ? Away, and do not ask to be made an empress." She returned : " Ah, king, how great thy pride ! But thy saying is unworthy of thy birth. Thou thinkest : 'None was there when I wedded Shakuntala ; such was thy device. But know that the divine Self who dwelleth in the heart was there, yea and the Sun and Moon, and Wind and Fire, the Sky, the Earth, the Waters, and the Lord of Death were there besides ; these thirteen witnesses, counting the Day and Night, the Twilights and the Law, cannot be deceived, but are aware of all that passes. I

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 355

know not if it be a punishment for any former sin that I am now denied. But here stands thy son altogether per fect ; yet no father makes him happy ! Dost thou feel no love for him who is thine own flesh and so like thyself ? Indeed thy heart is evil."

" Ah, Shakuntala," said the king, " were he my son I should be glad. But see, he is too great ; in such a little time no child could have grown so tall. Do not make this pretence against me, but depart." But as the king spoke there came a voice from Heaven. " Ho ! Maharaja," it cried, " this is thy child. Shakuntala has spoken truth." Then Dushyanta came down from his lion-throne and took All-tamer in his arms ; to Shakuntala he spoke with tears : " Mother Shakuntala, I was indeed glad when I saw thee. It was because of my kingly state that I denied thee ; for how should the people have believed that this was my son and heir ? Now the voice from Heaven has made the sonship clear to all, and he shall sit upon my lion-throne and shall come after me as the protector of the world, and his name shall be no more All- tamer, but shall be Bharata, because of the divine voice " ; and he prayed Shakuntala to pardon him ; but she stood still with folded hands and downcast eyes, too glad to answer, and too shy, now that all was well.

Bharata's prowess is the cause that there is now a Bharat-land ; the history thereof is told in the Mahabharata.

Nala and Damayanti

There was once a young king of Nishadha, in Central India, whose name was Nala. In a neighbouring country called Vidarbha there reigned another king, whose daughter Damayanti was said to be the most beautiful girl in the world. Nala was a very accomplished youth, well

Myths and Legends of the Hindus & Buddhists:End of page 356

practised in all the sixty-four arts and sciences with which kings should be acquainted, and particularly skilled in driving horses ; but, on the other hand, he was much too fond of gambling. One day as he walked in the palace garden, watching the swans amongst the lotuses, he made up his mind to catch one. The clever swan, however, knew how to purchase its freedom. "Spare me, good prince," it said, "and I will fly away to Vidarbha and sing thy praise before the beautiful Damayanti." Then all the swans together flew away to Vidarbha and settled at Damayanti's feet. Presently one of them began to talk to Damayanti. "There is a peerless prince in Nishadha," he said, "fairer than any man of God. Thou art the loveliest of women; would that ye might be wedded." Damayanti flushed, and covered her face with a veil as if a man had addressed her ; but she could not help wonder ing what Nala was like. Presently she said to the swan : "Perhaps you had better make the same suggestion to Nala himself." She felt quite safe in her father's garden, and hoped that Nala would fall in love with her, for she knew that her father was planning a Swayamvara, or own- choice, for her very soon, when she would have to accept a suitor at last.