Zafar

| Author:Laxman Burdak, IFS (R) |

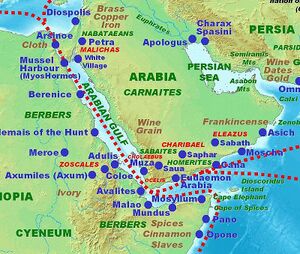

Zafar is an ancient Himyarite site situated in Yemen. Pliny has mentioned it as Sapphar.[1] Its ruins are now known as Dhafar. It was one of the chief cities of Arabia, standing near the southern coast of Arabia Felix.

Variants

- Ẓafār

- Saphar

- Sapphar (Pliny.vi.26)

- Dhafar (Arabic: ظفار)

- Ḥaql Yaḥḍib ("the field of Yaḥḍib")

Jat clans

Location

Zafar is 130 km south-south-east of today's capital, Sana'a, and c. 10 km southeast of Yarim. It lies in the Yemeni highlands at some 2800 m. Zafar was the capital of the Himyarites (110 BCE - 525 CE), which at its peak ruled most of the Arabian Peninsula.[2] For 250 years the tribal confederacy and allies' combined territory extended past Riyadh to the north and the Euphrates to the north-east.

History

From an archaeological perspective, the settlement's beginnings are not well known. The main sources consist of Old South Arabian Musnad inscriptions dated as early as the 1st century BCE. It is mentioned by Pliny in his Natural History, in the anonymous Periplus of the Erythraean Sea (both 1st century CE) as well as in the Geographia of Claudius Ptolemaeus (original 2nd century CE). At some point, presumably in medieval times, the coordinates of Ptolemy's map were incorrectly copied or emended so that subsequent maps placed the metropolis of "Sephar" in Oman, not in Yemen. Zafar in Yemen is attested more than 1000 years earlier than the place of the same name in Oman. (Smith 2001: 380). Written sources regarding Zafar are numerous, but heterogeneous in informational value. The most important source is epigraphic Old South Arabian. Christian texts shed light on the war between Himyar and the Aksumites (523 - 525). The Vita of Gregentios is a pious forgery created by Byzantine monks, which mentions a bishop who allegedly had his see in Zafar. Its use of language possibly indicates to a 12th century CE composition.[3] According to the Arab geographer and historian Al-Hamdani (c. 893-945), Zafar was also known by the name Ḥaql Yaḥḍib ("the field of Yaḥḍib").[4]

Individual finds belong to the early Himyarite period (110 BCE - 270 CE). Rare earlier finds were probably brought to the site from elsewhere. Most of the ruins and finds, however, appear to belong to the empire period (270 - 525). A few post-war Ge'ez inscriptions have survived at the site. Few finds can be securely dated to the late/post-empire period. After this there is little to suggest occupation until recent times. The excavated finds are important as texts shed little light on the material culture and art of this age. Moreover, recently the chronology of the main coin series has been criticized.[5]

Already a big established town, Sana'a and its fortress Ghumdan replaced Zafar as capital probably between 537 and 548. The textual basis for this topic is tenuous. At this time the archaeological record in Zafar and the surrounding region breaks off. No textual tradition articulates its destruction. Only an Aksumite church was recorded as being destroyed in 523. This church, likely built by missionary Theophilos the Indian, was destroyed by Dhu Nawas following the Himyarite conversion to Judaism. It was later restored after Aksum's successful invasion on Himyar in 524.

There is evidence that Zafar and settlement in general in the Yemenite highlands declined drastically in the 5th and 6th centuries.[6]Ideally, the viability of the city correlates declines drastically just after a relief of a crowned man was erected in what the excavator terms the Stone Building Site. The date of this relief and its inscription difficult, both perhaps to the mid 5th century. The occurrence in Zafar of ribbed amphorae manufactured in Aqaba/Ayla evidently in order to transport wine, shows the area just north of Aqaba to have been a fruitful agricultural area. On the other hand, D. Fleitmann has studied speleothems from al-Hootha cave in central Oman and has gathered information for megadroughts especially around 530. These may have afflicted the entire Peninsula.

A rectangular mapped surface area comprises 120 hectares. But the settlement is of uneven density and smaller than this. Zafar is the second largest mapped archaeological site in Arabia after Marib. Ancient settlement occurs inside and outside the ancient city defences. These have been estimated at 4000 metres long. The main fortress today is still referred to as the "Husn Raydan". A text by the medieval Yemenite author al-Hamdani mentions the names of city gates, most of which are named after the town to which they face. The main architectural ruins at Zafar include tombs and on the south-western flank of the Husn Raydan a 30 x 30 m square stone court, as preserved, originally probably a temple, to judge from the accumulation of cattle bones which it contained. It is located immediately north of a subterranean chambers and tombs. Immediately to the north are a row of storage chambers. The Husn Raydan and al-Gusr (standard Arabic: al-Qasr) 300 m to the north were once one fortification inside the city walls. Raydan South also was fortified and the ruined fortifications are best preserved here.

Musnad texts mention five royal palaces at Zafar: Hargab, Kallanum, Kawkaban, Shawhatan and Raydan, the state palace. Smaller ones, such as Yakrub, also find mention. Nearby Himyarite period settlements include Maṣna‘at Māriya (ancient Samiʻān) and the Ǧabal al-‘Awd settlement, 25 air km to the south-east.

The city was home to polytheist, Jewish and Christian communities. Jews dominated politically until 525. The ring-stone of Yiṣḥaq bar Ḥanina (common Jewish names, written in Aramaic; this exact name is attested coevally in the Talmud) is the earliest possible evidence for Jews in South Arabia. Surprisingly little evidence exists for the actual character and customs of these religions, far distant from their centres. Nor do the artefacts confirm a picture of the actual practices of Judaism and Christianity as we know them today. The vast majority of the sculpture suggests polytheistic belief was dominant in the population. One assumes in terms of religions a mixture of Christians, Jews and polytheists in late pre-Islamic times. An excavated 1.70 m tall image of a crowned figure represents a Christian king that wears an Aksumite-looking crown - the only image of that early religion to survive. At its apex Zafar had a flourishing sculptural industry attested to by a large number of relief fragments. But for a single example, the Heidelberg archaeologists were unable to positively identify churches or chapels on the site which no doubt existed [7]

From the 3rd to mid-6th centuries Zafar was a bustling international centre with a booming local and international trade. Yule estimated a 4th-century population of some 25,000, based partly on the surface area and population density.[8] Evidence of trade comes in the form of Late Roman period amphorae such as that depicted below. Many were produced in Aqaba, Jordan as we know from excavations there. Aqaba was a center where goods were loaded, re-packed and re-exported. About 500 such sherds and vessels came to light in Zafar, the number rivalling that at Adulis and Aqaba.[9] While wine is often mention as an import, livestock, textiles, meat, fish and fish sauce were also imported.

The contemporary environment is vastly inferior to that which provided the resource base for the early Himyarite tribal confederation. Despite some 500 mm precipitation per year, Water is scarce, upland soils are chronically eroded; the tree cover was eliminated perhaps in the empire period. Given the exhaustion of natural resources, civil strife, epidemics and megadroughts the Himyarite period population declined especially in the 6th century. Today, some 450 farmers inhabit the former capital.

Excavations at Ẓafār yielded 19 cultivated species including eight cereals, four oil and fibre plants, three pulses, three fruits and one spice. Hordeum is the most important cereal.[10] The Stone Building also yielded most of 6000 excavated animal bones. The Stone Building seems to have functioned as a slaughterhouse.[11]

An early 6th century relief statue has been identified as a king of Byzantine type,[12] perhaps a representation of king Sumūyafaʿ Ashwaʿ.

In 1970, Italian orientalist Giovānnī Garbinī discovered a Sabaean inscription on a column in Bayt al-Ašwāl near Zafar [Dhofār], whereon is engraved a later writing in Assyrian (Hebrew) script which reads: "The writing of Judah, of blessed memory, Amen shalom amen."[13] The script is believed to date to the 4th-century CE. The inscription attests to the multi-ethnic make-up of the peoples of South Arabia at that time.

Mention by Pliny

Pliny[14] mentions....Passengers generally set sail at midsummer, before the rising of the Dog-star, or else immediately after, and in about thirty days arrive at Ocelis28 in Arabia, or else at Cane29, in the region which bears frankincense. There is also a third port of Arabia, Muza30 by name; it is not, however, used by persons on their passage to India, as only those touch at it who deal in incense and the perfumes of Arabia.

More in the interior there is a city; the residence of the king there is called Sapphar31, and there is another city known by the name of Save. To those who are bound for India, Ocelis is the best place for embareation.

28 Now called Gehla, a harbour and emporium at the south-western point of Arabia Felix.

29 An emporium or promontory on the southern coast of Arabia, in the country of the Adramitæ, and, as Arrian says, the chief port of the increase-bearing country. It has been identified by D'Anville with Cava Canim Bay, near a mountain called Hissan Ghorab, at the base of which there are ruins to be seen.

30 Probably the modern Mosch, north of Mokha, near the southern extremity of Arabia Felix.

31 Its ruins are now known as Dhafar. It was one of the chief cities of Arabia, standing near the southern coast of Arabia Felix, opposite the modern Cape Guardafui.

External links

References

- ↑ Natural History by Pliny Book VI/Chapter 26

- ↑ Paul Yule, Himyar-Spätantike im Jemen/Late Antique Yemen (Aichwald 2007) ISBN 978-3-929290-35-6

- ↑ A. Berger (ed.), Life and Works of Saint Gregentios, Archbishop of Taphar… Millennium Studies in the Culture and History of the First Millennium C.E. vol. 76 (2006)

- ↑ Al-Hamdāni, al-Ḥasan ibn Aḥmad, The Antiquities of South Arabia - The Eighth Book of Al-Iklīl, Oxford University Press 1938, p. 20

- ↑ Armin Kirfel/Winfried Kockelmann/Paul Yule, Non-destructive Chemical Analysis of Old South Arabian Coins, 4th Century BCE – 3rd century, Archeometry vol. 53, 2011, 930–949. URL: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1475-4754.2011.00588.x/abstract

- ↑ cf. Jérémie Schiettecatte, D’Aden à Zafar villes d’Arabie du sud préislamique, Orient & Mediterranée Archéologie no 6, Paris 2011

- ↑ Paul Yule (ed.), Ẓafār, Capital of Ḥimyar, Rehabilitation of a ‘Decadent’ Society, Excavations of the Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg 1998–2010 in the Highlands of the Yemen, Abhandlungen Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft, vol. 29, Wiesbaden 2013, 32, ISSN 0417-2442, ISBN 978-3-447-06935-9

- ↑ Paul Yule (ed.), Ẓafār, Capital of Ḥimyar..

- ↑ M. Raith–R. Hoffbauer–H. Euler–P. Yule–K. Damgaard, Archaeometric Study of the Aqaba Late Roman Period Pottery Complex and Distribution in the 1st Millennium CE, Zeitschrift für

- ↑ Manfred Rösch & Elske Fischer, Charred plant remains, in Yule, Late Antique Arabia Ẓafār 2013, 187-94

- ↑ Margarethe and Hans-Peter Uerpmann, Animal remains in Yule, Late Antique Arabia Ẓafār 2013, 194-219

- ↑ Paul Yule, A Late Antique Christian king from Himyar, Southern Arabia, Old South Arabia, Antiquity, vol. 87, issue 338, December 2013, 1124–35

- ↑ Shelomo Dov Goitein, The Yemenites – History, Communal Organization, Spiritual Life (Selected Studies), editor: Menahem Ben-Sasson, Jerusalem 1983, pp. 334–339. ISBN 965-235-011-7

- ↑ Natural History by Pliny Book VI/Chapter 26