Trabzon

| Author:Laxman Burdak, IFS (R) |

Trabzon, historically known as Trebizond in English, is a city on the Black Sea coast of northeastern Turkey and the capital of Trabzon Province. Trabzon was located on the historical Silk Road.

Variants

- Trebizond (Anabasis by Arrian,p. 234.)

- Trebizond (English)

- Turkish pronunciation: [ˈtɾabzon];

- Ancient Greek: Tραπεζοῦς (Trapezous),

- Ophitic Pontic Greek: Τραπεζούντα (Trapezounta);

- Georgian: ტრაპიზონი (Trapizoni),

- Trapezus (Latin)

- Tara Bozan

- Trapizon

- Trebizonde (Fr.)

- Trapezunt (German)

- Trebisonda (Sp.)

- Trapesunta (It.)

- Trapisonda

- Tribisonde

- Terabesoun

- Trabesun,

- Trabuzan,

- Trabizond

- Tarabossan

Jat Gotras Namesake

- Tara = Tara Bozan = Trapezus (Pliny.vi.4)

Jat Gotras Namesake

- Tara = Tara Bozan = Trebizond (Anabasis by Arrian,p. 234.)

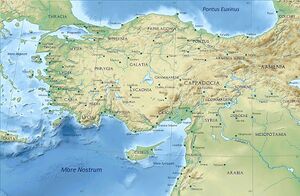

Location

Trabzon, located on the historical Silk Road, became a melting pot of religions, languages and culture for centuries and a trade gateway to Persia in the southeast and the Caucasus to the northeast.[1]

Name

The Turkish name of the city is Trabzon. It is historically known in English as Trebizond. The first recorded name of the city is the Greek Tραπεζοῦς (Trapezous), referencing the table-like central hill between the Zağnos (İskeleboz) and Kuzgun streams on which it was founded (τράπεζα meant "table" in Ancient Greek; note the table on the coin in the figure). In Latin, Trabzon was called Trapezus, which is a latinization of its ancient Greek name. Both in Pontic Greek and Modern Greek, it is called Τραπεζούντα (Trapezounta). In Ottoman Turkish and Persian, it is written as طربزون. During Ottoman times, Tara Bozan was also used.[2] In Laz it is known as ტამტრა (T'amt'ra) or T'rap'uzani,[3] in Georgian it is ტრაპიზონი (T'rap'izoni) and in Armenian it is Տրապիզոն Trapizon. The 19th-century Armenian travelling priest Byjiskian called the city by other, native names, including Hurşidabat and Ozinis.[10] Western geographers and writers used many spelling variations of the name throughout the Middle Ages. These versions of the name, which have incidentally been used in English literature as well, include: Trebizonde (Fr.), Trapezunt (German), Trebisonda (Sp.), Trapesunta (It.), Trapisonda, Tribisonde, Terabesoun, Trabesun, Trabuzan, Trabizond and Tarabossan.

In Spanish the name was known from chivalric romances and Don Quixote. Because of its similarity to trápala and trapaza,[11] trapisonda acquired the meaning "hullabaloo, imbroglio"[12]

History

The Venetian and Genoese merchants paid visits to Trabzon during the medieval period and sold silk, linen and woolen fabric. Both republics had merchant colonies within the city – Leonkastron and the former "Venetian castle" – that played a role to Trabzon similar to the one Galata played to Constantinople (modern Istanbul).[4]

Trabzon formed the basis of several states in its long history and was the capital city of the Empire of Trebizond between 1204 and 1461. During the early modern period, Trabzon, because of the importance of its port, again became a focal point of trade to Persia and the Caucasus.

Iron Age and Classical Antiquity:

Before the city was founded as a Greek colony the area was dominated by Colchians (west Georgian) and Chaldian (Anatolian) tribes. The Hayasa, who had been in conflict with the Central-Anatolian Hittites in the 14th century BC, are believed to have lived in the area south of Trabzon. Later Greek authors mentioned the Macrones and the Chalybes as native peoples. One of the dominant Caucasian groups to the east were the Laz, who were part of the monarchy of the Colchis, together with other related Georgian peoples.[4][5]

The city was founded in classical antiquity in 756 BC as Tραπεζούς (Trapezous), by Milesian traders from Sinope.[6] It was one of a number (about ten) of Milesian emporia or trading colonies along the shores of the Black Sea. Others included Abydos and Cyzicus in the Dardanelles, and nearby Kerasous. Like most Greek colonies, the city was a small enclave of Greek life, and not an empire unto its own, in the later European sense of the word. As a colony, Trapezous initially paid tribute to Sinope, but early banking (money-changing) activity is suggested to have occurred in the city already in the 4th century BC, according to a silver drachma coin from Trapezus in the British Museum, London. Cyrus the Great added the city to the Achaemenid Empire, and was possibly the first ruler to consolidate the eastern Black Sea region into a single political entity (a satrapy).

Trebizond's trade partners included the Mossynoeci. When Xenophon and the Ten Thousand mercenaries were fighting their way out of Persia, the first Greek city they reached was Trebizond (Xenophon, Anabasis, 5.5.10). The city and the local Mossynoeci had become estranged from the Mossynoecian capital, to the point of civil war. Xenophon's force resolved this in the rebels' favor, and so in Trebizond's interest.

Up until the conquests of Alexander the Great the city remained under the dominion of the Achaemenids. While the Pontus was not directly affected by the war, its cities gained independence as a result of it. Local ruling families continued to claim partial Persian heritage, and Persian culture had some lasting influence on the city; the holy springs of Mt. Minthrion to the east of the old town were devoted to the Persian-Anatolian Greek god Mithra. In the 2nd century BC, the city with its natural harbours was added to the Kingdom of Pontus by Pharnaces I. Mithridates VI Eupator made it the home port of the Pontic fleet, in his quest to remove the Romans from Anatolia.

After the defeat of Mithridates in 66 BC, the city was first handed to the Galatians, but it was soon returned to the grandson of Mithradates, and subsequently became part of the new client Kingdom of Pontus. When the kingdom was finally annexed to the Roman province of Galatia two centuries later, the fleet passed to new commanders, becoming the Classis Pontica. The city received the status of civitas libera, extending its judicial autonomy and the right to mint its own coin. Trebizond gained importance for its access to roads leading over the Zigana Pass to the Armenian frontier or the upper Euphrates valley. New roads were constructed from Persia and Mesopotamia under the rule of Vespasian. In the next century, the emperor Hadrian commissioned improvements to give the city a more structured harbor.[7] The emperor visited the city in the year 129 as part of his inspection of the eastern border (limes). A mithraeum now serves as a crypt for the church and monastery of Panagia Theoskepastos (Kızlar Manastırı) in nearby Kizlara, east of the citadel and south of the modern harbor.

Trebizond was greatly affected by two events over the following centuries: in the civil war between Septimius Severus and Pescennius Niger, the city suffered for its support of the latter, and in 257 the city was pillaged by the Goths, despite reportedly being defended by "10,000 above its usual garrison", and being defended by two bands of walls.[8]

Although Trebizond was rebuilt after being pillaged by the Goths in 257 and the Persians in 258, the city did not soon recover. Only in the reign of Diocletian appears an inscription alluding to the restoration of the city; Ammianus Marcellinus could only write of Trebizond that it was "not an obscure town."

Christianity had reached Trebizond by the third century, for during the reign of Diocletian occurred the martyrdom of Eugenius and his associates Candidius, Valerian, and Aquila.[9] Eugenius had destroyed the statue of Mithras which overlooked the city from Mount Minthrion (Boztepe), and became the patron saint of the city after his death. Early Christians sought refuge in the Pontic Mountains south of the city, where they established Vazelon Monastery in 270 AD and Sumela Monastery in 386 AD. As early as the First Council of Nicea, Trebizond had its own bishop. Subsequently, the Bishop of Trebizond was subordinated to the Metropolitan Bishop of Poti. Then during the 9th century, Trebizond itself became the seat of the Metropolitan Bishop of Lazica.[10]

Mention by Pliny

Pliny[11] mentions ....We next come to the rivers Iasonius17 on the site of the older city of Side, at the mouth of the Sidenus and Melanthius18 and at a distance of eighty miles from Amisus, the town of Pharnacea19, the fortress and river of Tripolis20; the fortress and river of Philocalia, the fortress of Liviopolis, but not upon a river, and at a distance of one hundred miles from Pharnacea, the free city of Trapezus21, shut in by a mountain of vast size.

17 Probably near the promontory of Jasonium, 130 stadia to the northeast of Polemonium. It was believed to have received its name from Jason the Argonaut having landed there. It still bears the name of Jasoon, though more commonly called Bona or Vona.

18 Sixty stadia, according to arrian, from the town of cotyora

19 Supposed to have stood on almost the same site as the modern Kheresoun or Kerasunda. It was built near, or, as some think, on the site of Cerasus.

20 Still known by the name of Tireboli, on a river of the same name, the Tireboli Su.

21 Now called Tarabosan, Trabezun, or Trebizond. This place was originally a colony of Sinope, after the loss of whose independence Trapezus belonged, first to Lesser Armenia, and afterwards to the kingdom of Pontus. In the middle ages it was the seat of the so-called empire of Trebizond. It is now the second commercial port of the Black Sea, ranking next after Odessa.

Mention by Pliny

Pliny[12] mentions ....Beyond this town (Trapezus) is the nation of the Armenochalybes22 and the Greater Armenia, at a distance of thirty miles. On the coast, before Trapezus, flows the river Pyxites, and beyond it is the nation of the Sanni23 Heniochi. Next comes the river Absarus24, with a fortress of the same name at its mouth, distant from Trapezus one hundred and forty miles.

22 The "Chalybes of Armenia." See p. 21.

23 Theodoret says that the Sanni, and the Lazi, subsequently mentioned, although subdued by the Roman arms, were never obedient to the Roman laws. The Heniochi were probably of Grecian origin, as they were said to have been descended from the charioteers of the Argonauts, who had been wrecked upon these coasts.

24 Or Apsarus, or Absarum. Several geographers have placed the site of this town near the modern one known as Gonieh. Its name was connected with the myth of Medea and her brother Absyrtus. It is not improbable that the names Acampsis and Absarus have been given to the same river by different writers, and that they both apply to the modern Joruk.

References

- ↑ http://www.karalahana.com/

- ↑ Campbell, Lawrence Dundas, The Asiatic annual register, or, A View of the history of Hindustan, and of the Politics, Commerce, Literature of Asia, London 1802 Page 3, Google books link

- ↑ Y.Dutxuri. "Türkçe Lazca sözlük / Çeviri / Online Çeviri / Lazuri.Com". www.Lazuri.com.

- ↑ Phoenix: The Peoples of the Hills: Ancient Ararat and Caucasus by Charles Burney, David Marshall Lang, Phoenix Press; New Ed edition (December 31, 2001)

- ↑ Ronald Grigor Suny, The Making of the Georgian Nation: 2nd edition (December 1994), Indiana University Press, ISBN 0-253-20915-3, page 45

- ↑ Romeo Bosneagu (22 February 2022). The Black Sea from Paleogeography to Modern Navigation: Applied Maritime Geography and Oceanography. Springer Nature. ISBN 978-3-03-088762-9. OCLC 1299382109.

- ↑ William Miller, Trebizond: The Last Greek Empire, 1926, (Chicago: Argonaut Publishers, 1968), p. 9

- ↑ William Miller, Trebizond: The Last Greek Empire, 1926, (Chicago: Argonaut Publishers, 1968), p. 9

- ↑ Miller, Trebizond, p. 10

- ↑ Hewsen, 46

- ↑ Natural History by Pliny Book VI/Chapter 4

- ↑ Natural History by Pliny Book VI/Chapter 4

Back to Jat Places in Turkey