Dacian: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

|} | |} | ||

</center> | </center> | ||

[[File:Dacia 125.png|thumb|Map showing Roman [[Dacia]] and surrounding peoples in 125 AD]] | |||

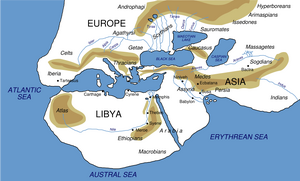

[[Image:Herodotus world map-en.svg.png|thumb|Getae on the World Map according to Herodotus]] | [[Image:Herodotus world map-en.svg.png|thumb|Getae on the World Map according to Herodotus]] | ||

'''Dacians''' were the ancient Indo-European inhabitants of the cultural region of [[Dacia]], located in the area near the [[Carpathian Mountains]] and west of the [[Black Sea]]. Classical authors are unanimous in considering them a branch of the [[Getae]]. [[Strabo]] specified that the Daci are the [[Getae]] who lived in the area towards the Pannonian plain (Transylvania), while the [[Getae]] proper gravitated towards the [[Black Sea]] coast ([[Scythia Minor]]). They are often considered a subgroup of the [[Thracian]]s.<ref>Waldman, Carl; Mason, Catherine (2006). Encyclopedia of European Peoples. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 1438129181.p.205</ref> | '''Dacians''' were the ancient Indo-European inhabitants of the cultural region of [[Dacia]], located in the area near the [[Carpathian Mountains]] and west of the [[Black Sea]]. Classical authors are unanimous in considering them a branch of the [[Getae]]. [[Strabo]] specified that the Daci are the [[Getae]] who lived in the area towards the Pannonian plain (Transylvania), while the [[Getae]] proper gravitated towards the [[Black Sea]] coast ([[Scythia Minor]]). They are often considered a subgroup of the [[Thracian]]s.<ref>Waldman, Carl; Mason, Catherine (2006). Encyclopedia of European Peoples. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 1438129181.p.205</ref> | ||

Revision as of 17:10, 29 September 2022

| Author: Laxman Burdak, IFS (R). |

Dacians were the ancient Indo-European inhabitants of the cultural region of Dacia, located in the area near the Carpathian Mountains and west of the Black Sea. Classical authors are unanimous in considering them a branch of the Getae. Strabo specified that the Daci are the Getae who lived in the area towards the Pannonian plain (Transylvania), while the Getae proper gravitated towards the Black Sea coast (Scythia Minor). They are often considered a subgroup of the Thracians.[1]

Variants

Distribution

They are often considered a subgroup of the Thracians.[5] This area includes mainly the present-day countries of Romania and Moldova, as well as parts of Ukraine,[6] Eastern Serbia, Northern Bulgaria, Slovakia,[7] Hungary and Southern Poland.[8]

The Dacians spoke the Dacian language, which has a debated relationship with the neighbouring Thracian language and may be a subgroup of it. Dacians were somewhat culturally influenced by the neighbouring Scythians and by the Celtic invaders of the 4th century BC.

Etymology of Dacians

The Dacians were known as Geta (plural Getae) in Ancient Greek writings, and as Dacus (plural Daci) or Getae in Roman documents,[9]but also as Dagae and Gaete as depicted on the late Roman map Tabula Peutingeriana. It was Herodotus who first used the ethnonym Getae in his Histories.[10]In Greek and Latin, in the writings of Julius Caesar, Strabo, and Pliny the Elder, the people became known as 'the Dacians'.[11] Getae and Dacians were interchangeable terms, or used with some confusion by the Greeks.[12][13] Latin poets often used the name Getae.[14] Vergil called them Getae four times, and Daci once, Lucian Getae three times and Daci twice, Horace named them Getae twice and Daci five times, while Juvenal one time Getae and two times Daci.[15] In AD 113, Hadrian used the poetic term Getae for the Dacians.[[16] Modern historians prefer to use the name Geto-Dacians.[17] Strabo describes the Getae and Dacians as distinct but cognate tribes. This distinction refers to the regions they occupied.[18] Strabo and Pliny the Elder also state that Getae and Dacians spoke the same language.[19][20]

By contrast, the name of Dacians, whatever the origin of the name, was used by the more western tribes who adjoined the Pannonians and therefore first became known to the Romans.[21] According to Strabo's Geographica, the original name of the Dacians was Δάοι "Daoi".[22] The name Daoi (one of the ancient Geto-Dacian tribes) was certainly adopted by foreign observers to designate all the inhabitants of the countries north of Danube that had not yet been conquered by Greece or Rome.[23]

The ethnographic name Daci is found under various forms within ancient sources. Greeks used the forms Δάκοι "Dakoi" (Strabo, Dio Cassius, and Dioscorides) and Δάοι "Daoi" (singular Daos).[24]

Latins used the forms Davus, Dacus, and a derived form Dacisci (Vopiscus and inscriptions).[25]

There are similarities between the ethnonyms of the Dacians and those of Dahae (Greek Δάσαι Δάοι, Δάαι, Δαι, Δάσαι Dáoi, Dáai, Dai, Dasai; Latin Dahae, Daci), an Indo-European people located east of the Caspian Sea, until the 1st millennium BC. Scholars have suggested that there were links between the two peoples since ancient times.[26][27][28] The historian David Gordon White has, moreover, stated that the "Dacians ... appear to be related to the Dahae".[29] (Likewise White and other scholars also believe that the names Dacii and Dahae may also have a shared etymology – see the section following for further details.)

By the end of the first century AD, all the inhabitants of the lands which now form Romania were known to the Romans as Daci, with the exception of some Celtic and Germanic tribes who infiltrated from the west, and Sarmatian and related people from the east.[30]

Etymology

The name Daci, or "Dacians" is a collective ethnonym.[31] Dio Cassius reported that the Dacians themselves used that name, and the Romans so called them, while the Greeks called them Getae.[32] Opinions on the origins of the name Daci are divided. Some scholars consider it to originate in the Indo-European *dha-k-, with the stem *dhe- 'to put, to place', while others think that the name Daci originates in *daca 'knife, dagger' or in a word similar to dáos, meaning 'wolf' in the related language of the Phrygians.[33]

One hypothesis is that the name Getae originates in Indo-European *guet- 'to utter, to talk'.[34] Another hypothesis is that Getae and Daci are the Iranian names of two Iranian-speaking Scythian groups that had been assimilated into the larger Thracian-speaking population of the later "Dacia".[35]

History

Early history: In the absence of historical records written by the Dacians (and Thracians) themselves, analysis of their origins depends largely on the remains of material culture. On the whole, the Bronze Age witnessed the evolution of the ethnic groups which emerged during the Eneolithic period, and eventually the syncretism of both autochthonous and Indo-European elements from the steppes and the Pontic regions.[36] Various groups of Thracians had not separated out by 1200 BC,[37] but there are strong similarities between the ceramic types found at Troy and the ceramic types from the Carpathian area.[38] About the year 1000 BC, the Carpatho-Danubian countries were inhabited by a northern branch of the Thracians.[39] At the time of the arrival of the Scythians (c. 700 BC), the Carpatho-Danubian Thracians were developing rapidly towards the Iron Age civilization of the West. Moreover, the whole of the fourth period of the Carpathian Bronze Age had already been profoundly influenced by the first Iron Age as it developed in Italy and the Alpine lands. The Scythians, arriving with their own type of Iron Age civilization, put a stop to these relations with the West.[40] From roughly 500 BC (the second Iron Age), the Dacians developed a distinct civilization, which was capable of supporting large centralised kingdoms by 1st BC and 1st AD.[41]

Since the very first detailed account by Herodotus, Getae are acknowledged as belonging to the Thracians.[42] Still, they are distinguished from the other Thracians by particularities of religion and custom.[43] The first written mention of the name "Dacians" is in Roman sources, but classical authors are unanimous in considering them a branch of the Getae, a Thracian people known from Greek writings. Strabo specified that the Daci are the Getae who lived in the area towards the Pannonian plain (Transylvania), while the Getae proper gravitated towards the Black Sea coast (Scythia Minor).

References

- ↑ Waldman, Carl; Mason, Catherine (2006). Encyclopedia of European Peoples. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 1438129181.p.205

- ↑ Strabo. Geographica [Geography] (in Ancient Greek). VII 3,12.

- ↑ Strabo. Geographica [Geography] (in Ancient Greek). VII 3,12.

- ↑ Dionysius Periegetes, Graece et Latine, Volume 1, Libraria Weidannia, 1828, p. 145.

- ↑ Waldman, Carl; Mason, Catherine (2006). Encyclopedia of European Peoples. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 1438129181.p.205

- ↑ Nandris, John (1976). Friesinger, Herwig; Kerchler, Helga; Pittioni, Richard; Mitscha-Märheim, Herbert (eds.). "The Dacian Iron Age – A Comment in a European Context". Archaeologia Austriaca (Festschrift für Richard Pittioni zum siebzigsten Geburtstag ed.). Vienna: Deuticke. 13 (13–14). ISBN 978-3-700-54420-3. ISSN 0003-8008.p.731

- ↑ Husovská, Ludmilá (1998). Slovakia: walking through centuries of cities and towns. Príroda. ISBN 978-8-007-01041-3. p. 187.

- ↑ Nandris, John (1976). Friesinger, Herwig; Kerchler, Helga; Pittioni, Richard; Mitscha-Märheim, Herbert (eds.). "The Dacian Iron Age – A Comment in a European Context". Archaeologia Austriaca (Festschrift für Richard Pittioni zum siebzigsten Geburtstag ed.). Vienna: Deuticke. 13 (13–14). ISBN 978-3-700-54420-3. ISSN 0003-8008.p.731

- ↑ Appian & 165 AD, Praef. 4/14-15,

- ↑ Herodotus. Histories (in Ancient Greek). 4.93–4.97.

- ↑ Fol, Alexander (1996). "Thracians, Celts, Illyrians and Dacians". In de Laet, Sigfried J. (ed.). History of Humanity. History of Humanity. Vol. 3: From the seventh century B.C. to the seventh century A.D. UNESCO. ISBN 978-9-231-02812-0.p.223

- ↑ Nandris 1976, p. 730: Strabo and Trogus Pompeius "Daci quoque suboles Getarum sunt"

- ↑ Crossland, R.A.; Boardman, John (1982). Linguistic problems of the Balkan area in the late prehistoric and early Classical period. The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 3. CUP. ISBN 978-0-521-22496-3.p.837

- ↑ Roesler, Robert E. (1864). Das vorromische Dacien. Academy, Wien, XLV.

- ↑ Roesler 1864, p. 89.

- ↑ Everitt, Anthony (2010). Hadrian and the Triumph of Rome. Random House Trade. ISBN 978-0-812-97814-8.p.151

- ↑ Fol 1996, p. 223.

- ↑ Bunbury, Edward Herbert (1979). A history of ancient geography among the Greeks and Romans: from the earliest ages till the fall of the Roman empire. London: Humanities Press International. ISBN 978-9-070-26511-3.p.150

- ↑ Bunbury, Edward Herbert (1979). A history of ancient geography among the Greeks and Romans: from the earliest ages till the fall of the Roman empire. London: Humanities Press International. ISBN 978-9-070-26511-3.p.150

- ↑ Oltean, Ioana Adina (2007). Dacia: landscape, colonisation and romanisation. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-41252-0.p.44

- ↑ Bunbury 1979, p. 151.

- ↑ Strabo & 20 AD, VII 3,12.

- ↑ Fol 1996, p. 223.

- ↑ Strabo & 20 AD, VII 3,12

- ↑ Mulvin, Lynda (2002). Late Roman Villas in the Danube-Balkan Region. British Archaeological Reports. ISBN 978-1-841-71444-8.

- ↑ Kephart, Calvin (1949). Sanskrit: its origin, composition, and diffusion. Shenandoah. p. 28: The Persians knew that the Dahae and the other Massagetae were kin of the inhabitants of Scythia west of the Caspian Sea.

- ↑ Chakraberty, Chandra (1948). The prehistory of India: tribal migrations. Vijayakrishna. p. 34: "Dasas or Dasyu of the RigVeda are the Dahae of Avesta, Daci of the Romans, Dakaoi (Hindi Dakku) of the Greeks"

- ↑ Pliny (the Elder) & Rackham 1971, p. 375.

- ↑ White, David Gordon (1991). Myths of the Dog-Man. University of Chicago. ISBN 978-0-226-89509-3.p.239

- ↑ Crossland & Boardman 1982, p. 837.

- ↑ Grumeza, Ion (2009). Dacia: Land of Transylvania, Cornerstone of Ancient Eastern Europe. Hamilton Books. ISBN 978-0-7618-4465-5.

- ↑ Florov 2001, p. 66.

- ↑ Barbulescu, Mihai; Nagler, Thomas (2005). The History of Transylvania: Until 1541. Coordinator Pop, Ioan Aurel. Cluj-Napoca: Romanian Cultural Institute. ISBN 978-9-737-78400-1.p.68

- ↑ Barbulescu & Nagler 2005, p. 68.

- ↑ Toynbee, Arnold Joseph (1961). A study of history. Vol. 2. OUP.p.435

- ↑ Dumitrescu, Vlad; Boardman, John; Hammond, N. G. L; Sollberger, E (1982). The prehistory of Romania from the earliest times to 1000 BC. The Prehistory of the Balkans, the Middle East and the Aegean World, Tenth to Eighth Centuries BC. The Cambridge Ancient History. CUP. ISBN 978-0-521-22496-3.p.166

- ↑ Dumitrescu, Vlad; Boardman, John; Hammond, N. G. L; Sollberger, E (1982). The prehistory of Romania from the earliest times to 1000 BC. The Prehistory of the Balkans, the Middle East and the Aegean World, Tenth to Eighth Centuries BC. The Cambridge Ancient History. CUP. ISBN 978-0-521-22496-3.p.166

- ↑ Dumitrescu, Vlad; Boardman, John; Hammond, N. G. L; Sollberger, E (1982). The prehistory of Romania from the earliest times to 1000 BC. The Prehistory of the Balkans, the Middle East and the Aegean World, Tenth to Eighth Centuries BC. The Cambridge Ancient History. CUP. ISBN 978-0-521-22496-3.p.166

- ↑ Parvan, Vasile (1928). Dacia. CUP.p.35

- ↑ Parvan, Vasile; Vulpe, Alexandru; Vulpe, Radu (2002). Dacia. Editura 100+1 Gramar. ISBN 978-9-735-91361-8.p. 49.

- ↑ Koch, John T (2005). "Dacians and Celts". Celtic culture: a historical encyclopedia. Vol. 1. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-851-09440-0.p. 549

- ↑ Herodotus & 440 BC, 4.93–4.97.

- ↑ Oltean, Ioana Adina (2007). Dacia: landscape, colonisation and romanisation. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-41252-0.p. 45.

Back to Variants of Jat