Achaemenid

| Author:Laxman Burdak, IFS (Retd.) |

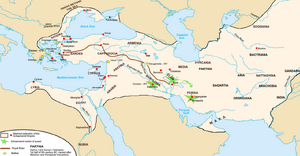

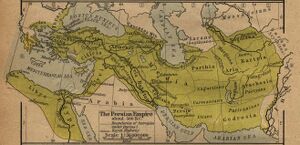

Achaemenid Empire (c. 550–330 BC), also called the (First) Persian Empire, was an empire based in Western Asia, founded by Cyrus the Great.

Variants

- Achaemenids (Anabasis by Arrian, p. 375)

- Achaemenid Empire

- Achaemenids

- Achaemenian

- Achaemenian Empire

- Haxāmanišiya

Location

Ranging at its greatest extent from the Balkans and Eastern Europe proper in the west to the Indus Valley in the east, it was one of the largest empires in history, spanning 5.5 million square kilometers, and was larger than any previous empire in history.

Mention by Pliny

Pliny[1] mentions Voyages to India.....Next to these is the nation of the Ori, and then the Hyctanis9, a river of Carmania, with an excellent harbour at its mouth, and producing gold; at this spot the writers state that for the first time they caught sight of the Great Bear.10 The star Arcturus too, they tell us, was not to be seen here every night, and never, when it was seen, during the whole of it. Up to this spot extended the empire of the Achæmenidæ11, and in these districts are to be found mines of copper, iron, arsenic, and red lead.

9 Possibly that now known as the Rud Shur.

10 Properly the "Seven Trions."

11 The Persian kings, descendants of Achæmenes. He was said to have been reared by an eagle.

History

It is equally notable for its successful model of a centralised, bureaucratic administration (through satraps under the King of Kings), for building infrastructure such as road systems and a postal system, the use of an official language across its territories, and the development of civil services and a large professional army. The empire's successes inspired similar systems in later empires. It is noted in Western history as the antagonist of the Greek city-states during the Greco-Persian Wars and for the emancipation of the Jewish exiles in Babylon. The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, was built in a Hellenistic style in the empire as well.

By the 7th century BC, the Persians had settled in the southwestern portion of the Iranian Plateau in the region of Persis (Pārsa),[2] which came to be their heartland.[3]

From this region, Cyrus the Great advanced to defeat the Medes, Lydia, and the Neo-Babylonian Empire, establishing the Achaemenid Empire. The delegation of power to local governments is thought to have eventually weakened the king's authority, causing resources to be expended in attempts to subdue local rebellions, and leading to the disunity of the region at the time of Alexander the Great's invasion in 334 BC.[4] This viewpoint, however, is challenged by some modern scholars who argue that the Achaemenid Empire was not facing any such crisis around the time of Alexander, and that only internal succession struggles within the Achaemenid family ever came close to weakening the empire.[5] Alexander, an avid admirer of Cyrus the Great,[6] conquered the empire in its entirety by 330 BC. Upon his death, most of the empire's former territory came under the rule of the Ptolemaic Kingdom and Seleucid Empire, in addition to other minor territories which gained independence at that time. The Persian population of the central plateau reclaimed power by the second century BC under the Parthian Empire.[7]

The historical mark of the Achaemenid Empire went far beyond its territorial and military influences and included cultural, social, technological and religious influences as well. Many Athenians adopted Achaemenid customs in their daily lives in a reciprocal cultural exchange,[8] some being employed by or allied to the Persian kings. The impact of Cyrus's edict is mentioned in Judeo-Christian texts, and the empire was instrumental in the spread of Zoroastrianism as far east as China. The empire also set the tone for the politics, heritage and history of modern Iran.[9]

The Achaemenid Empire was created by nomadic Persians. The name "Persia" is a Greek and Latin pronunciation of the native word referring to the country of the people originating from Persis (Old Persian: Pārsa), their home territory located north of the Persian Gulf in southwestern Iran.[10]

The Achaemenid Empire was not the first Iranian empire, as by 6th century BC another group of ancient Iranian peoples had already established the short lived Median Empire.[11] The Medes had originally been the dominant Iranian group in the region, freeing themselves of Assyrian domination and rising to power at the end of the seventh century BC, incorporating the Persians into their empire.

The Iranian peoples had arrived in the region of what is today Iran c. 1000 BC[12] and had for a number of centuries fallen under the domination of the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–609 BC), based in northern Mesopotamia. However, the Medes and Persians (together with the Scythians, Babylonians), Cimmerians, Persians and Chaldeans played a major role in the overthrow of the Assyrian empire and establishment of the first Persian empire.

The term Achaemenid means "of the family of the Achaemenis/Achaemenes" (Old Persian: Haxāmaniš; a bahuvrihi compound translating to "having a friend's mind").[13] Despite the derivation of the name, Achaemenes was himself a minor seventh-century ruler of the Anshan in southwestern Iran, and a vassal of Assyria.[14] It was not until the time of Cyrus the Great (Cyrus II of Persia), a descendant of Achaemenes, that the Achaemenid Empire developed the prestige of an empire and set out to incorporate the existing empires of the ancient east, becoming the vast Persian Empire of ancient legend.[15]

At some point in 550 BC, Cyrus rose in rebellion against the Medes (most likely due to their mismanagement of Persis), eventually conquering the Medes and creating the first Persian empire. Cyrus the Great utilized his tactical genius,[16] as well as his understanding of the socio-political conditions governing his territories, to eventually incorporate into the Empire neighbouring Lydia and the Neo-Babylonian Empire, also leading the way for his successor, Cambyses II, to venture into Egypt and defeat the Twenty-sixth Dynasty of Egypt.

Cyrus the Great's political acumen was reflected in his management of his newly formed empire, as the Persian Empire became the first to attempt to govern many different ethnic groups on the principle of equal responsibilities and rights for all people, so long as subjects paid their taxes and kept the peace.[17] Additionally, the king agreed not to interfere with the local customs, religions, and trades of its subject states,[18]a unique quality that eventually won Cyrus the support of the Babylonians. This system of management ultimately became an issue for the Persians, as with a larger empire came the need for order and control, leading to expenditure of resources and mobilization of troops to quell local rebellions, and weakening the central power of the king. By the time of Darius III, this disorganization had almost led to a disunited realm.[19]

The Persians from whom Cyrus hailed were originally nomadic pastoralists in the western Iranian Plateau and by 850 BC were calling themselves the Parsa and their constantly shifting territory Parsua, for the most part localized around Persis.[20] As Persians gained power, they developed the infrastructure to support their growing influence, including creation of a capital named Pasargadae and an opulent city named Persepolis.

Begun during the rule of Darius I "the Great" and completed some 100 years later,[21] Persepolis was a symbol of the empire serving both as a ceremonial centre and a center of government.[22] It had a special set of gradually progressive stairways named "All Countries"[23] around which carved relief decoration depicted scenes of heroism, hunting, natural themes, and presentation of the gifts to the Achaemenid kings by their various subjects, possibly during the spring festival, Nowruz. The core structure was composed of a multitude of square rooms or halls, the biggest of which was called Apadana.[24] Tall, decorated columns welcomed visitors and emphasized the height of the structure. Later on, Darius also utilized Susa and Ecbatana as his governmental centres, developing them to a similar metropolitan status.

Accounts of the Achaemenid family tree can be derived from either documented Greek or Roman accounts, or from existing documented Persian accounts such as those found in the Behistun Inscription. However, since most existing accounts of this vast empire are in works of Greek philosophers and historians, and since many of the original Persian documents are lost, not to mention being subject to varying scholarly views on their origin and possible motivations behind them, it is difficult to create a definitive and completely objective list. Nonetheless, it is clear that Cyrus and Darius were critical in the expansion of the empire. Cyrus is often believed to be the son of Cambyses I, grandson of Cyrus I, the father of Cambyses II, and a relative of Darius through a shared ancestor, Teispes. Cyrus the Great is also believed to have been a family member (possibly grandson) of the Median king Astyages through his mother, Mandane of Media. A minority of scholars argue that perhaps Achaemenes was a retrograde creation of Darius in order to reconcile his connection with Cyrus after gaining power.[25]

Ancient Greek writers provide some legendary information about Achaemenes by calling his tribe the Pasargadae and stating that he was "raised by an eagle". Plato, when writing about the Persians, identified Achaemenes with Perses, ancestor of the Persians in Greek mythology.[26] According to Plato, Achaemenes was the same person as Perses, a son of the Ethiopian queen Andromeda and the Greek hero Perseus, and a grandson of Zeus. Later writers believed that Achaemenes and Perseus were different people, and that Perses was an ancestor of the king.[27] This account further confirms that Achaemenes could well have been a significant Anshan leader and an ancestor of Cyrus the Great. Regardless, both Cyrus the Great and Darius the Great were related, prominent kings of Persia, under whose rule the empire expanded to include much of the ancient world.

Scythian connection

V. S. Agrawala[28] writes that Panini notices kantha-ending place names as being common in Varṇu (Bannu Valley) and the Usinara country between the lower course of the Chenab and Ravi River, and also instances some particular names such as Chihaṇa-kantham and

[p.468]: Maḍura-kantham, which rather appear as loan words (ante,p.67-68). In fact Kantha was a Scythian word for ‘town’, preserved in such names as Samarkand, Khokan, Chimkent etc.

The above data point to somewhat closer contacts between India and Persia during the reigns of Achaemenian emperors Darius (522-486 BC) and Xerxes (485-465 BC) as a result of their Indian conquests. This explains the use in India of such terms as Yavana, Parsu, Vrika, Kantha. To these we may add two others, viz. Jābāla (goat-herd) and hailihila (poison) mentioned by Panini (VI.2.38) which were really Semitic loan words.

This evidence points to Panini’s date somewhere after the time of these Achaemenian emperors.

The Districts

Herodotus divided the Achaemenid Empire into 20 districts. The following is a description of the ethnic makeup of the districts and the amount they paid in taxes, translated from Herodotus' Histories.

| District | Satrapies | Tribute |

|---|---|---|

| I | Ionians, Asian Magnesians, Aeolians, Carians, Lycians, Milyans, Pamphylians | 400 talents of silver |

| II | Mysians, Lydians, Lasonians, Cabalians, Hytennians | 500 talents |

| III | Hellespontine Phrygians, Phrygians, Asian Thracians, Paphlagonians, Mariandynians, Syrians | 360 talents |

| IV | Cilicians | 500 talents of silver along with 360 white horses (one for each day of the year); of the talents, 140 were used to maintain the cavalry force that guarded Cilicia |

| V | the area from the town of Posidium as far as Egypt, omitting Arabian territory (which did not pay taxes). All Phoenicia, Palestine Syria, and Cyprus, were herein contained. In the biblical Book of Ezra, this district is called Abar Nahara ("beyond the Euphrates river") | 350 talents |

| VI | Egyptians and the Libyans in the border towns of Cyrene and Barca | 700 talents, in addition to the money from the fish in Lake Moeris, and 120,000 bushels of grain for the Persian troops and their auxiliaries stationed in the White Castle at Memphis |

| VII | Sattagydians, Gandharans, Dadicae, Aparytae | 170 talents |

| VIII | Susa and the surrounding area, Cissia | 300 talents |

| IX | Mesopotamia (Babylonia and Assyria) | 1000 talents of silver and 500 eunuch boys |

| X | Ecbatana and the rest of Media along with the Paricanians and Orthocorybantians | 450 talents |

| XI | Caspians, Pausicae, Pantimathi, and Daritae | a joint sum of 200 talents |

| XII | Bactrians and all neighboring peoples as far as the Aegli | 360 talents |

| XIII | Pactyica, Armenians, and all the peoples as far as the Black Sea | 400 talents |

| XIV | Sagartians, Sarangians, Thamanaeans, Utians, Myci, and the inhabitants of the Persian Gulf islands (where prisoners or displaced people were sent) | together they paid 400 talents |

| XV | the Sacae and the Caspians | 250 talents |

| XVI | Parthians, Chorasmians, Sogdians, and Arians | 300 talents |

| XVII | Paricanians and Asiatic Ethiopians | 400 talents |

| XVIII | Matienians, Saspires, Alarodians | 200 talents |

| XIX | the Mushki, Tibareni, Macrones, Mossynoeci, Marres | 300 talents |

| XX | Indians | 360 talents of gold dust |

References

- ↑ Natural History by Pliny Book VI/Chapter 26

- ↑ http://www.utexas.edu/cola/centers/lrc/eieol/opeol-MG-X.html Macdonell and Keith, Vedic Index. This is based on the evidence of an Assyrian inscription of 844 BC referring to the Persians as Paršu, and the Behistun Inscription of Darius I referring to Pārsa as the area of the Persians. Radhakumud Mookerji (1988). Chandragupta Maurya and His Times (p. 23). Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 81-208-0405-8.

- ↑ David Sacks; Oswyn Murray; Lisa R. Brody; Oswyn Murray; Lisa R. Brody (2005). Encyclopedia of the ancient Greek world. Infobase Publishing. p. 256. ISBN 978-0-8160-5722-1.

- ↑ David Sacks; Oswyn Murray; Lisa R. Brody; Oswyn Murray; Lisa R. Brody (2005). Encyclopedia of the ancient Greek world. Infobase Publishing. p. 256. ISBN 978-0-8160-5722-1.

- ↑ David Sacks; Oswyn Murray; Lisa R. Brody; Oswyn Murray; Lisa R. Brody (2005). Encyclopedia of the ancient Greek world. Infobase Publishing. p. 256. ISBN 978-0-8160-5722-1.

- ↑ Ulrich Wilcken (1967). Alexander the Great. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-393-00381-9

- ↑ David Sacks; Oswyn Murray; Lisa R. Brody; Oswyn Murray; Lisa R. Brody (2005). Encyclopedia of the ancient Greek world. Infobase Publishing. p. 256. ISBN 978-0-8160-5722-1.

- ↑ Margaret Christina Miller (2004). Athens and Persia in the Fifth Century BC: A Study in Cultural Receptivity. Cambridge University Press. p. 243. ISBN 978-0-521-60758-2.

- ↑ Vesta Sarkhosh Curtis; Sarah Stewart (2005). Birth of the Persian Empire. I.B.Tauris. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-84511-062-8.

- ↑ Jamie Stokes (2009). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East, Volume 1. Infobase Publishing. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-0-8160-7158-6.

- ↑ Jamie Stokes (2009). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East, Volume 1. Infobase Publishing. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-0-8160-7158-6.

- ↑ Mallory, J.P. (1989), In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language, Archaeology, and Myth, London: Thames & Hudson.

- ↑ Schlerath p. 36, no. 9. See also Iranica in the Achaemenid Period p. 17.

- ↑ Jamie Stokes (2009). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East, Volume 1. Infobase Publishing. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-0-8160-7158-6.

- ↑ Kosmin, Paul J. (2014), The Land of the Elephant Kings: Space, Territory, and Ideology in Seleucid Empire, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-72882-0,p.31

- ↑ Simon Anglim; Simon Anglim; Phyllis Jestice; Scott Rusch; John Serrati (2002). Fighting techniques of the ancient world 3,000 BC – 500 CE: equipment, combat skills, and tactics. Macmillan. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-312-30932-9.

- ↑ Palmira Johnson Brummett; Robert R. Edgar; Neil J. Hackett; Robert R. Edgar; Neil J. Hackett (2003). Civilization past & present, Volume 1. Longman. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-321-09097-3.

- ↑ Palmira Johnson Brummett; Robert R. Edgar; Neil J. Hackett; Robert R. Edgar; Neil J. Hackett (2003). Civilization past & present, Volume 1. Longman. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-321-09097-3.

- ↑ David Sacks; Oswyn Murray; Lisa R. Brody; Oswyn Murray; Lisa R. Brody (2005). Encyclopedia of the ancient Greek world. Infobase Publishing. p. 256. ISBN 978-0-8160-5722-1.

- ↑ David Sacks; Oswyn Murray; Lisa R. Brody; Oswyn Murray; Lisa R. Brody (2005). Encyclopedia of the ancient Greek world. Infobase Publishing. p. 256. ISBN 978-0-8160-5722-1.

- ↑ Charles Gates (2003). Ancient cities: the archaeology of urban life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome. Psychology Press. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-415-12182-8.

- ↑ Charles Gates (2003). Ancient cities: the archaeology of urban life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome. Psychology Press. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-415-12182-8.

- ↑ Charles Gates (2003). Ancient cities: the archaeology of urban life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome. Psychology Press. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-415-12182-8.

- ↑ Charles Gates (2003). Ancient cities: the archaeology of urban life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome. Psychology Press. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-415-12182-8.

- ↑ Jamie Stokes (2009). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East, Volume 1. Infobase Publishing. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-0-8160-7158-6.

- ↑ David Sacks; Oswyn Murray; Lisa R. Brody; Oswyn Murray; Lisa R. Brody (2005). Encyclopedia of the ancient Greek world. Infobase Publishing. pp. 256 (at the bottom left portion). ISBN 978-0-8160-5722-1.

- ↑ Dandamayev

- ↑ V. S. Agrawala: India as Known to Panini, 1953, p.467-468