History of the Jats:Dr Kanungo/Reign of Raja Jawahar Singh

| Digitized & Wikified by: Laxman Burdak IFS (R) |

By K. R. Qanungo. Edited by Vir Singh. Delhi, Originals, 2003, ISBN 81-7536-299-5.

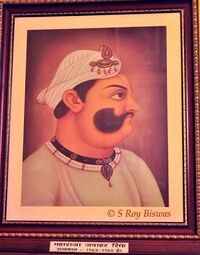

Chapter XI: Reign of Raja Jawahar Singh

Overthrow of Nahar Singh

[p.107]: While Jawahar Singh was engaged in the siege of WairXXIX (July-Novembr of rains 1765) Nahar Singh (the youngest son of Suraj Mal) was making preparations at Dholpur to strike a blow for the gadi of Bharatpur. It was quite apparent that his turn would come next, should Jawahar succeed in crushing Bahadur Singh. About this time Malhar Rao Holkar was on the other bank of the Chambal, carrying on hostilities against another Jat princlpality, Gohad.1 Nahar Singh commenced a correspondence with the Holkar in order to buy Maratha support and with the latter's aid to raise himself to the Raj. Jawahar Singh and Malhar Rao had an old score to settle ever since the Delhi expedition of 1764. The cunning Maratha had made a fool of the Jat by taking his money and at the same time baffling his object. But he had soon to repent his trickery when Jawahar, who was anything but a saint himself, bluntly refused to pay the unpaid half of the stipulated sum of twenty two lakhs, alleging breach of faith on the part of the Holkar. Malhar Rao seized this opportunity of making his claim good, and eagerly accepted the proposal

XXIX. The exact dates of operation Wair are not available. It began in the middle of August 1765 and ended in the first week of November 1765 in three months of the rainy season. U N Sharma, Maharaja Jawahar Singh, chapter III. - Ed.

1. Gohad is situated to the north-east of Gwalior. This principality was bounded on the west by the Gwalior territories, on the east by the Kali Sindu river, on the north by the Jamuna and on the south by the hills of Sirmur [?] See Rennell's atlas.

[p.108]: of Nahar Singh, whom, as usual the Holkar made his dharma putra (GOd-son), because Nahar Singh was rich enough to pay a good price for this paternal affectation.

Malhar Rao sent his troops across the Chambal and garrisoned the fort of Dholpur along with the men of Nahar Singh. Jawahar Singh summoned his brethren of Punjab,the Sikhs, to his aid, and arrived quickly on the bank of the Chambal to carry war into the enemy (December, 1765). One division of the Maratha army which had penetrated into the Jat country was surrounded and captured. Dholpur was next besieged and when it fell into the hands of Jawahar Singh, many Maratha chiefs who had taken shelter there during the retreat, became prisoners of war. Flushed with this success, Jawahar wanted to pursue Malhar Rao and clear Malwa of the Marathas. But the Sikhs refused to keep the field any longer as summer had already set in and they had suffered a good deal from the intolerable heat and scarcity of water. "Nahar Singh who had already retired to the army of Malhar lost his estate ... and was afterwardsabandoned by the Marathas to whom he wished to deliver the country .... He took refuge at Chopor, the citadel of a petty Rajput Raja-on the further side of Karauli, where he at last ended his life in despair by swallowing poison. His family retired to the protection of the Raja of Jalpur, where they are at present (i.e., 1768), having carried the most part of their riches and probably the knowledge (of the whereabouts) of the great part of the treasure of Suraj Mal, of whom Nahar Singh the destined successor, had been the confidant."2 (Wendel, Fr. MS., 65).

2. The Imad-us-Saadat, is the only Persian chronicle (Pers. text, p. 56) which notices the death of "the good natured" Nahar Singh by self-administered poison. On the 10th December, 1766, the news came from Jaipur that "Nahar Singh is dead of his disorder. This news has been received with utmost concern by Maharajah Jawahar Singh. All the cavalry officers who were in the army of Nahar Singh immediately returned to Jawahar Singh to consult what was most advisable on the occasion" [Pers. Cor. ii. 6]. The death took place evidently on the 6th or 7th of Dec. 1766.

Jawahar fights Raghunath Rao, 1767

[p.109]: The unrealised dream of Suraj Mal, namely to build up a great Jat confederacy extending from the Chambal to the Ravi dominating the whole of Northern India appeared to become well-nigh an accomplished fact by the establishment of more intimate relations between Jawahar Singh and the Sikhs, the recent victory of their united forces over the Marathas under Holkar, and the successful resistance of the Sikh commonwealth against the Abdali. Success opened new vistas of aggression to Jawahar who thought of widening the confederacy further so as to include the Jats of Northern Malwa, and raise a stronger barrier to Maratha invasion. The brave Rana Chattar Sal of Gohad had been carrying on for years a heroic struggle against the Marathas. The obstinate courage and undaunted spirit of the race shone no less brilliantly in Malwa than in the Punjab or Bharatpur. But they were losing ground every day, being only a handful, however brave, compared with the locust hordes, of the South. Should the Marathas succeed in over-throwing the Rana of Gohad, their full strength, Jawahar knew too well, would be pitted against him. "Proud of success over Malhar, Jawahar Singh resolved to give himself [Of his own accord?] help to the Rana [Chattar Sal] Jat, his ally, and thus finish the Marathas beyond the Chambal and outside his own country" [Wendel French MS. 65].

The Peshwa Madhu Rao viewed with alarm the growth of this formidable coalition and sent Raghunath Rao in the autumn of 1766, to retrieve the prestige of the Maratha armies in Hindustan. His army, together with those under the Holkar exceeded 60,000 horsemen, and had a choice artillery of more than 100 pieces. Raghunath began with the siege of Gohad, and made certain haughty demands upon Jawahar Singh, who was about this time suffering from a dangerous malady. As soon as he recovered, he " marched anew with the design to attack the Marathas, if they would not give up, of themselves the claims which they thought to have against him. But treason lurked in his own camp, which frustrated his object. Raghunath Rao seduced two of his principal chiefs, Anup Giri Goswain and Umrao Giri Goswain, (the leaders of the Nagas), from their allegiance

[p.110]: to the Jat Raja. The traitors promised to make Jawahir Singh a prisoner in his camp and hand him over to the Marathas, and they were to get, as a reward, certain territories in the direction of Kalpi. The spies of Jawahar Singh gave their master timely warning of this plot. At midnight Jawahar Singh got his troops ready and suddenly fell upon the camp of the Goswains. The traitors escaped with difficulty, but a considerable number of their followers were taken prisoners and their camp thoroughly pillaged. About 1400 horses, 60 elephants, 100 pieces of cannon, and other valuable booty, fell into the hands of Jawahar Singh. The dependents of the household of these two Goswains who were at Agra, Deeg and Kumher were brought to one place and kept under watch [Chahar Gulzar-i-Shujai MS.]3. About this time (Feb., 1767) Ahmad Shah Abdali made some progress in the Punjab and threatened to advance upon Delhi. Raghunath Rao and Jawahar Singh, who were equally interested in keeping the Abdali out of Hindustan, made up their quarrel in the face of this common danger. They met in friendship and adjusted their claims; the terms of the treaty were as follows:

1. The Maratha prisoners at Bharatpur, are to be released.

2. Jawahar Singh should execute a new agreement to pay up the balance of 15 lakhs of Rupees, due to Malhar Rao, after the conditions of the original agreement had been fulfilled [by the Marathas]

3. Raghunath Rao cedes to Jawahar Singh a small tract of the Rajput country, lying contiguous to the territory of the Raja on a yearly quit rent of 5 lakhs of Rupees [Pers. Cor. ii. 4-7)

The treaty was a make-shift arrangement, neither party meaning to respect it if its violation would bring greater advantages. The fear of the Abdali wore away towards the

3. Harcharan Das, author of the Chahar, makes some confusion about the date which he puts as 1179 A.H., the correct date being 1180, A.H. He estimates the gain of Jawahar as more than two krores, which, however, Wendel with perhaps greater accuracy puts as 30 lakhs. Nevertheless the account of Harcharan is substantially correct, and is corroborated by the version of Wendel, (French MS., 66).

[p.111]: middle of the year (1767) when the Sikhs considerably regained their ground. Jawahar Singh projected a campaign in the rainy season. "The country of the Raja of Atter4 and Bhant had been formerly tributary to the Marathas.... Jawahar Singh, seeing the Maratha parties so, weak, imagined that he had tere as much right as they, and took it into his head, without any other reason, to make the conquest. .. This enterprise also led him much further than he had proposed to himself. Going with superior forces to that side he seized in the rainy season (July-Sept.1767) all the dominions of the Marathas and other petty zamindars as far as Kalpi. If he had as much skill in preserving the recently conquered country, as he had success in seizing them, he could have been praised for his enterprises and would have been entirely glorious: but it is just this in which he failed more, namely in wisdom and moderation" [French MS" 66].

Raja Jawahar Singh and the English

A revolution of the greatest magnitude had in the meanwhile taken place in Bengal, and a new and foreign power, the English, now emerged as the most potent factor in the politics of Northern India. They paid at Gheria and Udaynala, the necessary price in blood for the kingdom of Bengal, which had been handed over to them by her treacherous sons at Plassey (1757). A high spirited and able prince who tried to do his duty fell a victim to the commercial greed of the English East India Company. Mir Qasim fled from his lost kingdom to Oudh. His new protector, the Nawab wazir Shuja-ud-daula, appeared in the field to dispute the fairprize with the victors. On the morrow of the battle of Buxar, the English merchant Company appeared with a monarch's sceptre before the astonished people and princes

4. Atter is situated north-east of Gwalior and due north of Gohad. Bhant is difficult to identify. It is perhaps the same place as Binde of Rennell's atlas, lying close to Atter and to the south-east of it. The territory of the above mentioned Raja was perhaps the tract between the [Chambal]] and the Kali Sindu rivers near their confluences with the Jamuna. These two places lie on the west and east of long. 79° and on lat. 26°-30'.

[p.112]: of India. The wazir of the empire bowed before it and received back his lost territories with an assurance of protection from his generous enemies. The homeless Emperor recognized the rising power and set up a melancholy Court at their fort of Allahabad, with the found hope of shining in borrowed light.

But the new masters of Bengal could not repose in peace so long as Mir Qasim was at large plotting against them, from his refuge among the Ruhelas. He had sent vakils to Ahmad Shah Durrani imploring his aid against the English. To this were added the urgent entreaties of Najib-ud-daula who was being crushed between the two millstones, the Jat and the Sikh, by their concerted pressure. The Bengal Government had every reason to fear an Abdali invasion on a grand scale against them, resulting in another Panipat on the border of their territory. The Ruhelas were bound both by interest and racial sympathy to the Abdali. Shuja-ud-daula could hardly be relied upon because the ruler of Oudh was to profit most by the extinction of the English Power in Bengal. Less reliable were the Marathas who found in the territorial ambition of the European merchants, the greatest obstacle to their national aspirations both in the north and the south. The Bengal Government did not fail to notice that there was only one Power in Hindustan with a well-organized government and a powerful army, namely the Jats of Bharatpur, who were likely to prove their surest allies; because situated as both powers were, one had nothing to gain by the destruction of the other, on the other hand both were equally interested in keeping back the Durranis and the Marathas. Raja Jawahar Singh could be of great service to the British in more than one way. First, he could keep the Abdali busy in the Punjab by backing the Sikhs. Secondly, should the invader threaten to march against the English, he could create a diversion in his rear or possibly draw off the invader to the siege of the Jat forts, giving time to the English to organize resistance. Thirdly, he could place the Emperor Shah Alam on the throne of Delhi and maintain him there with English help: a friendly Emperor on the throne of the Mughal capital and a powerful ally in possession of the surrounding tracts would mean the

[p.113]: domination of the whole empire by the British. If the Emperor would leave the English protection and turn hostile to them, Raja Jawahar Singh could equally check his anti-British designs. Such were the great possibilities of an alliance between the Jat and the English.

But the first approaches of alliance made by the English Government were not received with much eagerness by the Jat. The Governor of Bengal wrote a letter to Raja Jawahar Singh (19 Aug., 1765), requesting him to dismiss the notorious Somru who had taken shelter and service with him; on his fulfilling that condition, the prospect of a defensive alliance was held out to him (Pers. Cor. i. 427). Raja Jawahar Singh had no hostile design against the English in affording refuge to Somru, who was entertained simply because the Raja had the need of a European captain to organize an infantry brigade for him. He did not like the mandatory tone of the Governor's letter; and as there was no enemy at his doors, he chose to take no serious notice of it. Clive foresaw the necessity of creating against the Abdali and the Maratha, a confederacy admitting the Jats and the Ruhelas also to the advantages of a defensive alliance with the English. He advocated this scheme in the congress at Chapra, but the majority was opposed to him on the ground of the heavy responsibilities it was likely to impose on the Government of Bengal. At the beginning of the year 1767, the Durrani king invaded the Punjab with a firm resolution to root out the Sikhs, and then to reinstate Mir Qasim on the throne of Bengal. He inflicted several defeats upon the Sikhs, penetrated as far as the Sutlej, and threatened to advance upon Delhi. The progress of his arms created a stir among all the native powers and none was more alarmed than the Bengal Government. The emergency which Clive had foreseen now arose. His successor Mr. Verelst asked the wazir, who had some influence with the Jats, once his father's allies, to open egotiations5 with them afresh.

5. The correspondence which passed between the Bengal Government and the wazir, reveals how eagerly the English sought to win over Raja Jawahar Singh. (Letters Nos. 201, 234, 255, Pers. Cor. ii. pp. 69, 77).

[p.114]: At this time Raja Jawahar Singh with the [Abdal]]i on one flank and Raghunath Rao on the other, was himself equally anxious for an alliance with the English. He now entered with alacrity into the scheme of a combined resistance to the Abdali.

Impressed by the fidelity of the English to their engagements, Jawahar wished to cement the proposed defensive union with them by a regular offensive and defensive alliance. He had made approaches through Muhammad Reza Khan and sent a letter to him by the hand of one Srikrishan, a dependent of his, requesting the Khan "to use his influence with the gentlemen of Calcutta to seal a vow of friendship and alliance with the writer [Jawahar Singh], so that he may be able to make war successfully with the Shah and obtain success .... [bringing about] the tranquility of the people of God and the settlement of the affairs of Hindustan .... [the writer] asked to be considered now as invariably attached .... [to the English] and determined to preserve with them a union in which there will never be least failure .... Should it be thought advisable, the writer will place His Majesty Shah Alam on the throne of Delhi and proclaim Ghazi-ud-din Khan wazir, [the writer] makes one proposal beforehand, namely, that the fort of Ranthambhar should be placed in the writer's hands" (ibid, p. 87, letter No. 296, dated April 12, 1767). The Governor of Bengal wrote in reply directing the Khan that "Raja Jawahar Singh may be informed that if he is really sincere in his desire to enter into an alliance with the English, he should send a trustworthy vakil to Banaras, where the writer [the Governor] is going, and where the subject can be thoroughly discussed" (ibid, p. 91; letter No. 315, dated 20th April, 1767).

Accordingly Jawahar Singh appointed one Don Pedro De Silva as his vakil (ibid, p. 129). The wazir informed the Governor that he "does not place dependence on the Ruhelas or repose any credit in them; but Jawahar Singh can be relied upon to some extent. Writer imagines that he [Jawahar] will gladly embrace 'our' alliance .... If Jawahir Singh is inclined to enter into an alliance and compact, and give his firm and unshaken promise to take up the sword for the service of the English Company, and if the writer, and the

[p.115]: English engage to give him assistance should the Shah invade his territories, in what terms could an answer be returned to him? Hopes that the Governor will ponder over this question and inform the writer of his sentiments in order that he may act agreeably thereto" [ibid, p. 99, letter No. 346, dated April 25, 1767]. Jawahar had kept the Shah in good humour by professing loyalty and obedience to him. His vakil waited upon the Shah on the 17th of February 1767, and a special envoy, Karimullah, son of Raja Jawahar Singh's head munshi Yahya Khan went soon afterwards with presents of various sorts to the Shah's camp (Pers, Cor. ii. 26, 32). There cannot be any better proof of the sincerity and honesty of the Jat Raja than the fact that after the date (12th April) of his opening negotiations for an alliance with the English, he kept no correspondence with the Shah which might be construed as a proof of bad faith towards them.

Assured of English help against the Abdali, Jawahar did not hesitate to provoke the hostility of the Marathas. Immediately after the conclusion of this alliance, he began to occupy some places taking advantage of the temporary retirement of the Marathas. The Governor in a letter to the wazir expresses his anxiety at the conduct of his new ally and asks him "to keep the eye of observation on the movements of those restless people [the Marathas], while Jawahar Singh enforces his pretensions to those districts which once acknowledged the authority of the Marathas" [ibid, p. 145].

About this time a war broke out in the Deccan between the English Government and Haidar Ali who was joined by the Nizam of Hyderabad, of late an ally of the English. The Marathas also seeing the Madras Government very hotly pressed by their enemies, contemplated hostility against the English. Raja Januji Bhonsla made certain irritating demands upon the Governor of Bengal, who very courageously resented them and wrote to the envoy of Januji to tell his master that "it will not be difficult to convince him [Januji] that the English are not less formidable enemies than sincere friends." (Ibid, p. 152. letter No. 583, dated Sept. 27, 1967). As the Abdali had retired to his country, virtually defeated by the Sikhs, the Marathas were thinking of reconquering

[p.116]: Hindustan. It was rumoured that Raja Januji and Raghunath Rao had united their forces for invading Hindustan. The Peshwa Madhu Rao also felt the pulse of the wazir through his vakil who wrote a letter: "It is rumoured here that the Europeans are not on good terms with the wazir and give him innumerable troubles. If so ... the wazir will .... favour him with letters for Sri Mant [Raghu Nath Rao]6 and Madhu Rao, the writer's gracious Master. [The vakil] tells him [the wazir] to send a deed under his seal making over the suba of Bengal to the Marathas, that they may collect revenue there" (ibid, p. 181; letter No. 667, Nov. 1767). The wazir forwarded the letter to the Governor and wrote in reply to the Maratha vakil that there was the most perfect friendship subsisting between the English and his Government.

Aprehensive of a serious Maratha invasion of Hindustan the defensive union wich, had been formed against the Abdali was now set in motion by the English Government against the Marathas. The Jats had already begun hostilities and the wazir was firm in his attachment to the English. The Marathas became discouraged by their state of isolation in Hindustan and consequently gave up their aggressive designs.

Raja Jawahar had received letters from the Governor for re-adjusting their old alliance to meet the new exigency and build up a more solid confederacy to preserve the peace of Hindustan against all enemies, including the Marathas. The Raja signified his regard for the friendship of the English and sent Padre Don Pedro to Calcutta "to communicate to the Governor the secrets of his heart" (ibid., p. 171; letter No. 642, Oct. 31, 1767).

Jawahar's Pilgrimage to Pushkar (Nov.-Dec. 1967)

Raja Jawahar Singh had reached the very summit of his power and glory by a series of brilliant victories. Proud of his army and wealth, he thought he could with impunity, insult and oppress his weaker neighbours who appeared like so many pigmies to his delusive vision. Angry providence soon hurled him down from the pinnacle of fortune and

6. Somewhat confusing because Sri Mant in the Maratha correspondence is generally applied to the Peshwa himself.

[p.117]: humbled his pride. "Delivered from all the troubles which the Marathas could give him, and also in a certain degree above them feared by the Ruhelas, and respected, beyond what he could claim elsewhere, master of a vast country flourishing and tranquil, he knew not," says Father Wendel, "how to taste long the advantages of his good fortune or rather he himself thought to interrupt it and wished to invert by his own hands the high fortune, which up to the present had not ceased to follow him; in spite of the efforts which often he had made himself to banish it." [French MS., 67].

Jawahar owed his misfortune to the unhappy issue of a quarrel which he himself most wantonly provoked with Maharaja Madho Singh of Jaipur. As close neighbours the rulers of Bharatpur and Jaipur had causes enough for bad blood. The latter could not be expected to watch with satisfaction the growth of the new born Jat Power, a permanent menace to his State. It was nevertheless true that the Bharatpur principality could not in its infancy have lived an prospered witout the patronage of Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh, an this was gratefully acknowledged by Jawahar's father and grand-father who always showed more out of goodness than bear - proper respect and homage to the ruling House of Jaipur, as to a superior and patron. But the accession of "Madho Singh - against whom Suraj Mal had fought on behalf of Raja Iswari Singh - disturbed this cordial relation; the haughtiness of the new ruler offended the Jat chief, who ceased to attend the darbar of Jaipur on the day of the Dashera. As human nature goes, patrons become enemies when their patronage is no longer required; so this coldness developed into bitter enmity when Jawahar succeeded his father, and haughtiness was pitted against haughtiness. Raja Jawahar Singh believed too seriously-in his reputed Yadava descent to feel, like his ancestors, any diffidence, due to consciousness of a less exalted birth, in claiming equality with the Rajput ruling houses of the Solar and Lunar races. Once, it is said, some advisers of the Raja, told him that he ought to show defference to the Maharaja of Jaipur, at least in consideration of his descent from Rama, who bridged the ocean. "Well," replied Jawahar, "if his

[p.118]:ancestor threw a bridge across the ocean my ancestor [Shri Krishna held up Govardhan hill for seven days on his little finger!" His father and grand-father were content to be addressed as Braj-Raj [King of Braj, i.e., the Mathura district] as a compliment to their sovereignty over that tract. But Jawahar as if to pique the ruler of Jaiur assumed the lofty title of Maharaja Sawai Jawahar Singh Bharatendra [Lord Paramount of India, Fr. MS., 71] and, vying in splendour and magnificence made his Court outshine that of his neighbour. "In short", as Ghulam Ali, the author of Shah Alam Nama says, "Jawahar raised his head to the stature of Maharaja Madho Singh" (Pers. MS., p. 3). The ruler of Jaipur who had not the power to resent it, bore the humiliation in silence. But his aggressive adversary at last compelled him to take up arms for preserving the honour of his house and the sanctity of the soil of Amber.

Battle of Maonda 14.12.1767: No incident of the history of the eighteenth century is so green in the memory of the country-side, and nothing is so much distorted by national prejudices as the armed pilgrimage of Jawahar Singh to Pushkar through Jaipur territory - the fierce battle of Mawda (Maonda), and his inglorious retreat. The Jat attributes the disaster to the intrigue of the Rao Raja Pratap Singh the founder of the Alwar State - who having quarrelled with his suzerain, Madho Singh of Jaipur, fled for protection to Suraj Mal, and afterwards incited Jawahar Singh against his overlord. He is said to have treacherously deserted Jawahar and directed the Jaipur army to attack the Jats when entangled in a difficult pass. The Rajput version on the other hand is that Jawahar Singh demanded the surrender of the wife of Nahar Singh, which the Maharaja of Jaipur declined because the lady feared ill-treatment at the hands of Jawahar. She afterwards swallowed poison,7 lest a calamity should befall her protector on her account. The brave Naruka chief whose patriotism prevailed over his sense of gratitude for the hospitality of the Jat, came over to the army of Jaipur and fought for upholding the honour of his country. No more authentic account of it can be found than that in the unbiased narrative

7. Appendix, p. 111, Life of Maharaja Sawai Iswari Singh (in Hindi) by Thakur Narendra Singh Verma, Vaidic Press, Ajmer.

[p.119]: of Father Wendel, who penned it within twelve months of its occurrence.

"The Jats .... had for many years past some quarrels (with the Raja of Jaipur) regarding a small tract of country8 not far from Deeg, where there was always subject for misunderstanding, as ordinarily happens on the frontier between different territories. It went at last to the extent of having troublesome consequence by an open rupture which appeared inevitable. This affair, however, had been, or seemed about to be settled by compromise. Jawahar Singh proud of his forces9 and riches and puffed up by his fortune, did not cease to treat haughtily the Rajputs and their Raja, and also with a certain insolence which was neither seasonable nor decent for him .... He at this time took the fancy to go and make a pilgrimage to the Pushkar lake in Marwar territory, close to Ajmer and to have also an interview with the Rathor Raja of that country, with whom he commenced a sort of limited friendship .... Having then with this design assembled all his forces, more to make a show than from necessity, in spite of the dissuasions of others, he began the journey of more than 70 kos outside his own country with a numerous10 army, as if he was going to fight against all the Rajputs and conquer their territories" [French MS., p. 67].

With banners unfurled and drums beating, the Jat proudly set is foot upon the soil of Amber and marched

8. This refers to Kama (long. 77°-20' lat. 27°-40'), situated about 15 miles north-west of Deeg. Kama was for a long time a bone of contention between the two States. Raja Ranjit Singh Jat got it from Mahadji Sindhia and since then has been in possession of the Bharatpur Rajas.

9. Jawahar Singh had a large and well-disciplined army led by able European captains. Somru had been in his employ since 1765 and M. Rene Madec, the renowned French general joined his service in the month of June or July of the year 1767 (Le Nabob Rene Madec, p. 45]. The restless mind of the Raja hit upon this adventure as an opportunity to test the minds of his army upon the Kachhwahas.

10. Harcharan, author of the Chahar-Gulzar-i-Shujai gives an exaggerated estimate of Jawahar's army: "Sixty thousand horses, one lakh of footmen, and two hundred guns."

[p.120]: triumphantly towards the holy lake, doing great damage to the Rajput territory. A momentary stupor had seized the Kachhwaha, but the heir of Man Singh and Mirza Raja Jai Singh could not long bear the defiant flourishes of the enemy (challenging him to a trial of strength). The whole of Amber, peasants and lords, rose to their feet to strike a blow for her honour. Maharaja Madho Singh, whose fiery Sisodia blood had been cooled down by old age and misfortune, was roused to a sense of his honour by his feudal chiefs. They said to him in indignation and sorrow, "Will you suffer to be thus insulted by a man whose father and grand-father were the tenants of your house and who stood with folded hands before your ancestors?" "By no means" replied the Raja "so long as the seed of Kachhwahas remains on earth." The levy en masse of Amber was ordered. Dalel Singh and other Rajput chiefs with twenty thousand horsemen and an equal number of infantry occupied the road by which Jawahar was expected to return.

Raja Jawahar Singh had reached the holy lake and after finishing his ablutions there, he halted for some days and sealed a vow of friendship by the exchange of turbans with Raja Bijay Sing Rathor, who met him there. The Rajputs were watching his return march; but his army being a large and powerful one, they did not offer him a pitched battle. Jawahar Singh avoided the direct route, and tried to make his way through Tornawati, a hilly country, thirty miles north of Jaipur. Rao Raja Pratap Singh who had been for several years a refugee at Bharatpur, now deserted Jawahar Singh, and joined the forces of Jaipur. He counselled an attack upon the Jat army while it was threading its way trouh a defile and the famous battle of Maonda was fought on the 14th Dec. 1767.

This battle has been the theme of many a stirring ballad; each side claiming the victory and extolling the heroism of their respective chiefs. The memory of this ancient feud still causes some heart-burning to both peoples. M. Madec who had accompanied Raja Jawahar Singh to Pushkar, and fought for him on a occasion, has left the following account of event. "The latter [Raja of Jaipur], piqued by the insult, followed the Jats, with his army, on their return. He had

[p.121]: 16,000 cavalry. Near Jaipur the Jats had to traverse a defile. They made their baggage go ahead, in such a way as to cover them. They hoped to escape the pursuit of their enemies, but were overtaken and attacked at a disadvantage. The Jats routed them by a counter-march. The artillery and infantry of the assailants were too slow. The Jats took advantage of it to enter the defile, preceded by their baggages at a distance of three leagues. The Raja of Jaynagar engaged in pursuing them in the gorge, and overtook them in the middle. The Jats then made a half-turn to offer battle.

They engaged towards noon. The enemy cavalry put at the very first, that of the Jats to the rout. The latter saved themselves by falling back upon their baggage, crying out that all was lost; the peasants then plundered a great part of the baggage. But the party of Madec and that of the German Sombre, who laboured in that affair with all the bravery and prudence of a great soldier, restored the battle and defeated the Raja of Jaynagar. Nearly 10,000 men fell in the two armies together, among them nearly all the generals of the enemy's army. The victors, deprived of their baggage, of which they could not find even the fragments, were themselves put to great hardship. They had to abandon a part of their artillery11 on account of the state of the road" (Le Nabob Rene Madec, pp. 49, 50).

11. Wendel thus describes the plight of the vanquished: "The fortune of the Jats remains shaken and the result has been entirely fatal to them. They have returned home despoiled, stupefied and overthrown, and Jawahar Singh, having left there all his train of artillery (70 pieces of different calibres), tents and baggage" [French MS, 68]. Suraj Mal the bard of Bundi, commemorates this episode thus:

- ताबत छत्र अरु तोप कोस लुट्टे कच्छबाहन।

- भरतनेर गए जट्ट मारवाय सिपाहन॥

- जित्ते कुरम जोध नाग जट्टन गिनि नाहर।

- समरु बेहुनजु संग जाय पकरेहिं जवाहर॥

- संस्कृत भुजंग ससिमान सक 1824 हमतक यह जंग हुब।

- जयनेर विजय जट्टन भजन भइ विदित आव्रज भुब॥

The Kachhwahas captured the Umbrella of Royalty, guns and treasure. The Jat, after having his soldiers slaughtered, fled to Bharatpur. As the king of beasts looks upon the elephant [as his prey] so did the Kurma [Kachhwaha] warriors look upon the Jats. Had not Somru been in the company Jawahar would have been captured .... The battle took place in the year 1824 [of the Vikrama era). This victory of [the ruler of] Jaipur, and the defeat of the Jats became known to the furthest limit of the land of Braj.

[p.122]: On that fateful day Jawahar Singh fought with his accustomed vigour and tenacity, and maintained his ground till the darkness of evening brought him respite. Dalel Singh the brave commander-in-chief of the Jaipur army fell in the fight with three generations of his descendants and none but boys of ten remained to represent the baronial houses of Jaipur. The aggressor, however, was overthrown and once more it was proved that God is not always with the heaviest battalion as tyrants believe.

Jawahar' s struggle with his numerous enemies

Maharaja Jawahar Singh now presented a sorry figure, shorn of his power and splendour, derided by enemies, and deserted by friends. "Now is the moment," was the exultant cry that his enemies raised from every quarter. At the first report of his defeat, the country beyond the Chambal rose against him and it was lost as suddenly as it had been gained. Maharaja Madho Singh entered the Jat territories with 60,000 soldiers and took ample vengenance by ravaging them. Nawab Musavi Khan Baloch of Farrukhnagar (who had been released a year before from his confinement at Bharatpur), and the Ruhelas were ready to co-operate with the Rajputs. His unprincipled allies, the Sikhs began desolating his two outlying provinces (Wendel, 69; Le Nabob Rene Madec, 50). The Emperor Shah Alam II was invited by Maharaja Madho Singh either to come in person, or if that was not possible, to send some English commander with a battalion of European troops to reinforce him. "Now is the opportunity" he wrote, "which Your Majesty should seize .... your old and hereditary servant and the other Rajas in his confederacy are ready in allegiance with their levies .... The royal seat of Akbarabad will fall to Your

[p.123]: Majesty." [Pers. Cor. ii. 224]. The Emperor sent-though he disavowed it afterwards- "a royal mandate to Raja Madho Singh to advance and take possession of the fort of Agra, after effecting a junction with Musavi Khan's forces who was to proceed from Delhi [ibid, 234].

Every one counselled Jawahar to make a compromise with the Rajputs; but the Jat preferred breaking to bending and to abide by the chances of a war than to sue for terms from his victorious enemy. He decided to carry on war by buying over the Sikhs. He paid them 7 lakhs of Rupees to keep them away from plundering his territory and opened negotiation with them to enlist into his service 20,000 of them. The lethargy caused by the late defeat was shaken off, and warlike preparations commenced in earnest. M. Madec got an increase of Rs. 5,000 to his monthly allowance for increasing his corps. [Le Nabob Rene Madec, p. 50].

Meanwhile a plot was being hatched by Nawab Shuja-ud-daula to crush Jawahar's power. The wazir suggested to the Emperor a comprehensive and plausible plan, which, if acted upon, would have brought about the extinction of the Jat power. He asked the Emperor first to dissuade the Sikh sardars from assisting Jawahar Singh by the offer of the same amount of subsidy on behalf of Madho Singh and the grant of royal favours; secondly to send a prince of the royal line with farmans to the Ruhela chiefs to unite them under him and conquer that part of Jawahar Singh's territories that lay on the left of the Jamuna and bordered on the Ruhela possessions - the conquered territories were to be left in the Ruhela hands in order to ensure their loyalty. The wazir most enthusiastically offered his services to carry out his plan against Jawahar Singh: "Whenever His Majesty thinks fit to call upon the writer [Shuja-ud-daula] he will perform what he has represented." [Pers. Cor. ii. 234, 235, letter No. 835, dated March 2, 1768]. In short Jawahar's enemies were drawing a net around him, which appeared too strong for him to break through. At this critical moment the attitude of the Bengal Government became the decisive factor. Leaving active hostility out of account, it the English had even secretly countenanced this scheme, the Emperor, Shuja-ud-daula, Najib Khan and all the Ruhelas would have been

[p.124]:in full march against Jawahar Singh whom even the Sikhs could not have saved. But the Bengal Government, with an integrity and firmness rare in the politics of the eighteenth century, stood true to their alliance with Jawahar, and vigorously checkmated all the hostile designs of his enemies. The emperor and Shuja-ud-daula dare not move without the consent of the Governor of Bengal. When Madho Singh found no response to his appeal from any quarter and saw the Sikhs coming to the assistance of [Jawaar Singh]], hemade peace with the Jats and retired to his own country before the arrival of the dreaded cavalry of the Punjab.

Death of Jawahar Singh

Reverses failed to teach any moderation to Jawahar Singh. Strife was the very breath of his nostrils and without it life seemed to have had no charm for him. "The war having been ended on this side [against Madho Singh], it broke out on another. The Jat Raja sent Madec to besiege a fort where another Rajput clan was entrenched. In a month and a half Madec succeeded in climbing one of the bastions, but the assault failed on account of his being abandoned by the Indian troops who were frightened by the terrible fire of the defenders. He clung to the foot of the breach for making a second attack. The garrison in fear capitulated. [Le Nabob Rene Madec, 50].

Never did the fierce will and the untiring energy of Raja Jawahar Singh shine forth more brilliantly than during the 6 or 7 months following his reverse in Rajputana. With great rapidity he mastered a desperate situation and brought it back to normality. The late reverse appeared to have done little injury to him, and he was up again on his legs. His arms were recovering their wonted lustre and his territories their erstwhile prosperity. He threw himself heart and soul into re-organizing his army, and particularly increasing the European corps and the field artillery. His authority was re-established everywhere in his dominion and his name respected and feared abroad. His neighbours trembled at the prospect of a more tremendous outburst of his wrath; fortunately for them the swift hand of destiny silenced this unspent volcano.

[p.125]: The story of Jawahar's violent death (July, 1768) runs as follows: "It is said that Jawahar Singh formed a friendship with a soldier whom he admitted to very great intimacy and showed him regard and honour exceeding proper limits and raised him from a low to a high rank. The degree of this man's companionship made him superior [in status] to other courtiers. By chance, some improper acts were done by-him. and Jawahar Singh forbade the soldier to come to his private audience and bedroom, disgraced and humbled him, and made him contemptible in his own eyes and in those of the public. This man, being roused to a sense of honour sought for some means of killing Jawahar Singh.

One day Jawahar Singh with a small party rode out for hunting. This soldier, at that time, took horse and arrived w1th sword and shield, and at a place where Jawahar Singh was standing carelessly with a few men he struck him down with is sword crying out "This is the punishment for the disgrace and insult you did to me." This event happened in the month of Safar, 1182 H. (June-July 1768).12

Popular tradition, as recorded by Growse (Mathura, 25), attributes the murder of Jawahar to the instigation of his enemy, Maharaja Madho Singh of Jaipur. The sudden death of Jawahar Singh within 8 months of his quarrel with the Raja of Jaipur who undoubtedly benefited by this event, possibly gave colour to this unjust calumny which has no foundation in truth, or documentary proof. As regards the murder of Jawahar Singh the author of the Siyar13 says: "He gave a chobdar named Sada, predominant authority over the whole body of his sardars, and thus made them all

12. Chahar Guizar MS.: this date, though not very definite, is undoubtedly correct. From a letter of the Emperor to the Governor of Bengal, dated 27th August, 1768, we learn that Jawahar died before that date (Pers. Cor. ii. 299). Don Pedro De Silva formally announces the death of Jawahar Singh and the accession of his successor Ratan Singh to the Govrnment of Bengal on the 7th Sept., 1768 (ibid. p. 304).

13. The translator of the Siyar puts it thus: "He put one Haidar, a chobdar of his own at the head of his affairs and army: a measure that lost him the heart of his troops, and shocked his commanders to such a degree that one of them resolved to fall upon him and put him to death. This man having a favourable moment, killed him upon his very Masnad!" (Eng. trans. iv. 34). Sada is perhaps the more correct reading, because Abdul Karim Kashmiri, author of the Bayan-o-Waqa, says that "Jawahar Singh was slain by an oppressed Brahman" (MS. p. 302). However it is likely that Mustapha, the translator, who used only one manuscript, quite naturally preferred the reading, Haidar, to Sada, a rather obscure name. But he cannot be excused for his want of fidelity to the original text which is little likely to have varied so greatly. Those who put implicit faith in translations should take a warning from this.

[p.126]: extremely oppressed-they instigated one to slay Jawahar Singh. A short time after his occupying the throne of his father he was killed treacherously." [Pers. text, Siyar, iv. 34]. M. Madec, who was in the service of Jawahar Singh at the time of his death, does not accuse anybody: stating simply that the Raja was murdered by an unknown man, who beheaded him with one stroke of his sword [Le Nabob Rene Madec, 50].

Character and policy of Raja Jawahar Singh

Raja Jawahar Singh lacked neither the soldierly qualities nor the administrative capacity of his father. Apparently engrossed with the exciting game of war, he was never remiss in his attention to the details of the civil administration, or indifferent to the promotion of the arts of peace. His Court was splendid and magnificent, the best market in Hindustan for the valour of a soldier, skill of an architect.14 and the flattering harp of a native bard. He paid his troops more regularly and more handsomely than his father, and there was no occasion when he did not generously recompense good services. "His finances were in the best order and his people the least imposed on in the country and he had political views" which appeared very wise to his European military chief [Le Nabob Rene Madec, 51]. Heleft behind him not a set of turbulent and rebellious military chiefs, but a numerous and well-disciplined army, commanded by loyal officers, who faithfully obeyed even a contemptuous voluptuary like Ratan Singh, his successor.

14. A detailed account of the buildings of Jawahar Singh along with those of Suraj Mal and other Jat Rajas will be found in a subsequent section. The Jat style of Architecture.

[p.127]: His clemency spared his younger brothers, though he knew them to be so many thorns in the path of his adopted minor son. At times, he could rise to the height of generosity and forgive is worst enemiles, as we find in the release of Bahadur Singh and Nawab Musavi Khan Baloch - dangerous political prisoners - on the occasion of his nephew's birth. Friends remembered him as a night-errant, bold, magnificent and open-handed, and enemies as a man, capricious and obstinate, a narrow bigot and blood-thirsty tyrant- a comet in the political sky of Hindustan.

Raja Jawahar Singh, unlike his father, had little control over his passions, no respect for antiquity and tradition, no catholicity of heart. At any rate, tradition, no doubt prejudiced to a great extent, associates his name with the despoilation of the relics of the Mughal imperial grandeur. He is said to have seated himself on the black marble throne of the Emperor Jahangir-a sacrilege which made the proud seat of the Great Mughal, to burst in pique as it were, leaving a crack which is still to be seen! It was perhaps during the regime of Jawahar Singh, the strongest and most vindictive among the Jat Rajas that "The Great Mosque of Agra was change into a market: the grain merchants had orders to expose their goods for sale there. The butchers' shops were closed. They [the Jats} made very severe prohibition of the slaughter of oxen, cows and also of kids [?] .... All public profession of the Muhammadan religion was interdicted under very harsh treatment. The muazins were ordered to cease their functions. One man gave the azan but the Government of Agra pulled his tongue out."15 Though it is but human to retaliate, it was certainly unworthy of the son of Suraj Mal who had honoured the bones of a Muslim

15. Le Nabob Rene Madec, 47. M. Madec says: "I saw, some years ago, that unfortunate man, who begged alms, supplied with a letter from the mullahs of the Great Mosque of Agra, in which they attested that the faithful one, exercising the ministry with which he was charged, had been so cruelly treated by the idolators" [ibid].

It is doubtful whether some deception was not practised upon the credulity of the stranger, which is, by no means uncommon to this day. M. Madec does not specify the name of Jawahar Singh but says "When the Jats became possessors of Agra," the known character of Jawahar Singh warrants the above inference.

[p.128]: refugee- Shamsher Bahadur, by building a mosque over it at Deeg. [Imad, 203].

Jawahar Singh too prematurely and too violently changed what was more or less a tribal confederacy into a centralized State, and rendered himself a despot with the help of mercenary troops. He crushed life out of the State and the people; the one ceased to grow of itself, and, the other, cowed by mercenaries and relegated to a secondary position, lost their vitality and spirit. Suraj Mal built up a structure which reflected faithfully the political instinct and tradition of his own people. But to the eye of Jawahar Singh, it appeared antiquated, inelegant, lacking in sympathy and compactness, unworthy of a Prince, though comfortable for a Jat. As in society Jawahar regulated his life according to the then up-to-date fashion of a Prince or an Amir, discarding the old simplicity of his father, so in politics he breathed the atmosphere of imperialistic Delhi. People to a certain extent imitated the fashion of the Prince, and one could see [the vices, maxims, etiquette of] Delhi near Deeg, Kumher and Bharatpur as some of our countrymen see to-day London in Bombay and Calcutta. With the new society established in these places, the customs, dress, buildings, language and all in general, had changed, among the Jats.16 Jawahar seemed to move with the spirit of the time when he set about transforming a feudal confederacy into a centralized, despotic government of the Mughal type. But as he was eager to make himself master of his own household, so was every Jat, who resented autocracy and whose inner-self remained the same, in spite of all his outward polish. Without making a tactful compromise, he removed every powerful opponent to his fierce will and thereby recklessly destroyed a considerable amount of national energy and efficiency. If the Jats were the ancient Yadavas, Kansa (the uncle of Shri Krishna, who usurped despotic authority over the Yadava confederacy with the help of mercenary fighters, and oppressed his kinsmen) was perhaps reborn among them in the person of Maharaja Sawai Jawahar Singh Bharatendra!

16. Wendel, French MS., 40, 41. He adds: "It must be confessed that at the same time [in spite of considerable polish] one may always notice their naive rusticity in the midst of the very brilliant fortune with which they see themselves surrounded" [ibid, 41].