Sakarya

| Author:Laxman Burdak, IFS (R) |

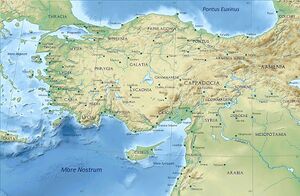

Sakarya is the third longest river in Turkey. It runs through the region known in ancient times as Phrygia. It was considered one of the principal rivers of Asia Minor (Anatolia) in classical antiquity, and is mentioned in the Iliad[1] and in Theogony.[2] Its name appears in different forms as Sagraphos,[3] Sangaris,[4]or Sagaris.[5]

Variants

- Sangarius River (Anabasis by Arrian, p. 77.)

- Sagaris (Pliny.vi.2)

- Sagraphos[6]

- Sangaris[7]

- Sagaris.[8]

- Sangia was a small town in the east of ancient Phrygia, near Mount Adoreus and the sources of the Sangarius.(Strabo.xii. p. 543). Its site is unlocated.[9]

- Sakara River

- Turkish: Sakarya Irmağı

- Greek: Σαγγάριος,

- Romanized: Sangarios

- Latin: Sangarius

- Sakaria

Jat Gotras Namesake

- Saka +Arya = Sakarya = Sangarius River (Anabasis by Arrian, p. 77.)

- Sakarwar = Sakarya = Sangarius River (Anabasis by Arrian, p. 77.)

- Sangu = Sangarius River (Anabasis by Arrian, p. 77.)

- Sangwa = Sangarius River (Anabasis by Arrian, p. 77.)

- Sangwan = Sangarius River (Anabasis by Arrian, p. 77.)

- Sangar = Sangarius River (Anabasis by Arrian, p. 77.)

Jat Gotras Namesake

- Sagar = Sagaris (Pliny.vi.2)

- Saka +Arya = Sakarya = Sagaris (Pliny.vi.2)

History

In Geographica, Strabo wrote during classical antiquity that the river had its sources on Mount Adoreus, near the town of Sangia in Phrygia, not far from the border with Galatia,[10] and flowed in a very tortuous course: first in an eastern, then toward the north, next the north-west and finally the north through Bithynia into the Euxine (Black Sea).

Part of its course formed the boundary between Phrygia and Bithynia, which in early times was bounded on the east by the river. The Bithynian part of the river was navigable and was celebrated for the abundance of fish found in it.

Its principal tributaries were the Alander, the Bathys, the Thymbres and the Gallus.[11]

The source of the river is the Bayat Yaylası (Bayat Plateau), which northeast of Afyon. Joined by the Porsuk Çayı (Porsuk Creek), close to the town of Polatlı, the river runs through the Adapazarı Ovası (Adapazarı Plains) before it reaches the Black Sea. The Sakarya was once crossed by the Sangarius Bridge, constructed by Eastern Roman Emperor Justinian I (r. 527–565).

In the 13th century, the valley of the Sakarya was part of the border between the Eastern Roman Empire and the home of the Söğüt tribe. By 1280, Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos had constructed a series of fortifications along the river to control the area, but a flood in 1302 changed the course of the river and made the fortifications useless.[12] The Söğüt tribe migrated across the river and later established the Ottoman Empire.

From downstream to upstream, the Sakarya has four dams: Akçay, Yenice, Gökçekaya and Sarıyar.

Mention by Pliny

Pliny[13] mentions....After passing the mouth of the Bosporus we come to the river Rhebas9, by some writers called the Rhesus. We next come to Psillis10, the port of Calpas11, and the Sagaris12, a famous river, which rises in Phrygia and receives the waters of other rivers of vast magnitude, among which are the Tembrogius13 and the Gallus14, the last of which is by many called the Sangarius.

9 Now the Riva, a river of Bithynia, in Asia Minor, falling into the Euxine north-east of Chalcedon.

10 Probably an obscure town.

11 On the river Calpas or Calpe, in Bithynia. Xenophon, in the Anabasis, describes it as about half way between Byzantium and Heraclea. The spot is identified in some of the maps as Kirpeh Limán, and the promontory as Cape Kirpeh.

12 Still known as the Sakaria.

13 Now called the Sursak, according to Parisot.

14 Now the Lef-ke. See the end of c. 42 of the last Book.

External links

References

- ↑ Homer. Iliad. Vol. 3.187, 16.719.

- ↑ Hesiod, Theogony, 344.

- ↑ Schol. ad Apollon. Rhod. 2.724.

- ↑ Constantine VII, De Administrando Imperio 1.5

- ↑ Ovid, ex Pont. 4.10 17; Solin 43; Pliny. Naturalis Historia. Vol. 6.1.

- ↑ Schol. ad Apollon. Rhod. 2.724.

- ↑ Constantine VII, De Administrando Imperio 1.5

- ↑ Ovid, ex Pont. 4.10 17; Solin 43; Pliny. Naturalis Historia. Vol. 6.1.

- ↑ Richard Talbert, ed. (2000). Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World. Princeton University Press. p. 62, and directory notes accompanying.

- ↑ Strabo. Geographica. Vol. xii. p.543. Page numbers refer to those of Isaac Casaubon's edition.

- ↑ Periplus of Pseudo-Scylax, p. 34; Apollon. 2.724; Scymnus. 234, foil.; Strab. xii. pp. 563, 567; Dionys. Perieg. 811; Ptol. 5.1.6; Steph. B. sub voce Liv. 38.18; Plin. Nat. 5.43; Amm. Marc. 22.9.

- ↑ Imber, Colin. The Ottoman Empire, 1300-1650 : the structure of power (Third ed.). London. p. 6. ISBN 1352004968. OCLC 1034613389.

- ↑ Natural History by Pliny Book VI/Chapter 1

Back to Rivers