Deotek

| Author:Laxman Burdak, IFS (R) |

Deotek (देवटेक) is a village in Nagbhir tahsil in Chandrapur district of Indian state of Maharashtra, India. An inscription in Brahmi was obtained from this place of the period of Ashoka Maurya (300-332 BCE).[1] It is placed now in the Central Museum, Nagpur.[2]

Origin

Variants

History

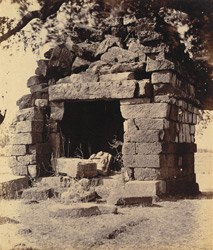

Photograph of the ruins of a small laterite temple at Deotek, taken by Joseph David Beglar in 1873-74. Deotek is located in the Chandrapur district of the modern state of Maharashtra. The site shown in this photograph is described by J.D. Beglar in his 'Report of a tour in Bundelkhand and Malwa': "The temple is small, consisting simply of a cell and its entrance; it may have had a small portico or a mandapa attached, as the ground in front is covered with cut blocks; but it could not have been large, and indeed, the temple is of the kind usually built without mandapas. The stone (laterite) it is built of, has been quarried on the spot...The temple faces east."[3]

Deotek Inscriptions

A village called "Deotak" 2–3 km from Nagbhid, There was a stone slab containing two distinct inscriptions, the characters of one being of the kind known as those of the 'Ashoka' edicts and those of the other belonging to the 'Vakataka' period. Both of them are fragmentary but mention a name Chikambari, which Mr Hira Lal has identified with Chikmara, a village close to Deotek. The slab has now been removed to the Nagpur Museum.

Deotek Stone Inscription of Rudrasena I

[p.1]: Deotek is now a small village, about 50 miles south-east of Nagpur. It has an old temple in a dilapidated condition and a large inscribed slab. The place was visited by Cunningham’s assistant, Beglar, in the year 1873-74. He has described the temple and the inscribed slab in Cunningham’s Archaeological Survey Reports, Vol. VII, pp. 123-25. From the pencil impressions Beglar took at the time, Cunningham published an eye-copy of the two inscriptions on the slab and his transcript of their texts, without any translation or interpretation, in the Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, Vol. I (First Edition), pp. 28-29. Though the inscriptions are very important, none noticed them until I drew attention to them at the Mysore session of the All-India Oriental Conference held in December 1935. They have been edited with facsimiles by me in the Proceedings and Transactions1 of the Conference.

I visited Deotek in October 1935 and took estampages which showed some better readings than Cunningham’s eye-copy. On the other hand, some letters which Cunningham read in the last line of the earlier record have since then disappeared, evidently owing to the peeling off of the surface of the slab, which had for a long time been used as a seat by village boys and cowherds while tending cattle. As described by Beglar2, ‘ the inscribed slab is an oblong trapezoid of rough-grained, quartzy sandstone, worn smooth in places by the feet of villagers, it being situated in the thick shade of a magnificent tamarind tree, on the side of the village road, and thus offering a capital resting place and seat; the stone is nine feet long, three and a half feet broad at one end, and two feet ten inches at the other, with straight sides; it bears two distinct inscriptions ’. The stone has since been removed to the Central Museum, Nagpur.

The earlier of the two inscriptions is inscribed lengthwise and is in four lines..... The characters are of the early Brahmi alphabet, resembling, in many cases, those of the Girnar edicts of Ashoka. The language is early Prakrit as in the Girnar edicts. At least the first three lines of this inscription seem to have originally extended to the right-hand edge of the slab ; for, traces of isolated letters in the first line, which are in no way connected with the second inscription, can still be marked on the original stone. Besides, the sense of the first two lines, which are fairly legible, appears to be incomplete in the absence of their right-hand half 3. It would again be strange if the engraver, selecting a large slab nine feet long and commencing to incise it lengthwise, had ended his lines about the middle of it, leaving out nearly a half at the right end. For these reasons I cannot accept Beglar’s view that ‘ the second inscription was cut evidently with some regard for the prior inscription.

1. P.T.A.I.O.C., 1935, pp. 63 f.

2.C.A.S.R., Vol. VII, p. 124.

3. One would, for instance, expect at the end of line 1 the names of animals and the seasons in which their capture and slaughter were prohibited. Cf. Asoka’s pillar edict V.

[p.2]: as it does not interfere with or injure it’1 On the other hand, the later inscription seems to have been incised after the earlier one was chiselled off to make room for it.

The object of the earlier inscription was to record the command of some lord [Sami] who is called ‘king’ in line 4), prohibiting the capture and slaughter (evidently of some animals in certain seasons as in Asoka’s fifth pillar edict, or, maybe, throughout the year) and declaring some punishment for such as dared to disobey it. The third line mentions executive officers (āmachā—amātyāh) whose duty may have been to enforce these orders. The last line contains the date 14, denoting probably the regnal year in which the record was incised.

This edict seems to have been issued by a Dharmamahāmātra in the fourteenth year after the coronation of Ashoka. From the fifth rock edict of the great Buddhist Emperor we learn that these Mahāmātras were first appointed by Asoka in the thirteenth year after his coronation, i.e., a year prior to the date of this record. One of the duties assigned to them was to prevent the capture and slaughter of animals. It is not unlikely that the Dharmamahāmātra who was in charge of ancient Vidarbha caused the present record to be incised at Chikamburi mentioned in line 1, which seems to have been then a place of great importance, to proclaim the command of the great Emperor to his subjects living in the neighbourhood2.

The second inscription which concerns us here is in five lines3, which are inscribed breadthwise, commencing from the narrow end of the slab. Like the earlier inscription, it also has suffered considerable damage. Some letters in the first four lines have either altogether disappeared or become illegible, owing to the wearing away and peeling off of the surface of the slab. Besides, a channel 4" in breadth has been cut right through the middle of the inscription, which has evidently resulted in the further loss of some more letters4.

Like the Eran inscription of Samudragupta, the present record is inscribed in the box-headed variety of the southern alphabet of about the fourth century A.C.....The language is Sanskrit and the whole inscription is in prose.

The object of this inscription is to record the construction of a temple or place of religious worship (dharma-sthāna)5 by king Rudrasena at Chikkamburi. It may be noted in this connection that there is at present a small plain structure of laterite in a dilapidated condition just where the inscribed slab was noticed. ‘ The temple is small, consisting simply of a cell and its entrance; it may have had a small portico or a mandapa attached, as the ground in front is covered with cut blocks; but it could not have been large and indeed the temple is of the kind usually built without a mandapa5’ The existing structure

1. C.A.S.R., Vol. VII, p. 124.

2. In some of his edicts Asoka orders his officers to get his edicts engraved on stone pillars, rocks and stone slabs throughout the districts in their charge. See his Rupnath rock inscription, line 5, and Sarnath pillar inscription, lines 9-10.

3. There are faint traces of two letters (Siddham ?) in a much smaller size in line 6.

4. The channel could not have existed at the time the inscription was incised; for, in one case at least (viz., in vamsa. tasya) we are sure that it has caused the loss of one letter viz., jā. Beglar also has remarked, “Long afterwards, when no one could read the inscriptions, this great slab, large enough to occupy the breadth of the sanctum of a temple, was considered to form into an argha and in the process the inscriptions were remorselessly sacrificed ”. C.A.S.R., Vol. VII, pp. 124-25.

5. The chief temple in the capital was called Vaijayika-dharma-sthāna.

6. C.A.S.R., Vol. VII, p. 124.

[p.3]: is quite plain. The only decoration it seems to have had was in the form of a scroll on its door frame, two fragments of which are lying in front of it. The door seems to have been 4' 4" in breadth and about 4' in height. The lintel has, in a recess in the middle, a small image of two-armed Ganapati, measuring 6 " in breadth and 8.5 " in height. ‘ The roof of the sanctum is formed of intersecting squares and has a pyramidal shape cut up exteriorly into gradually diminishing steps. Temples of this type can be seen in the adjoining villages of Panori (पानोरी) and Armori (आर्मोरी)1 . There is a large image of Ganapati placed in the cell, but it seems to be of a later age. The temple was originally dedicated to Shiva. The linga has now disappeared, but from the socket in an old argha lying nearby, it seems to have been a large one, about 13" in diameter. Such lingas are found round about Mansar near Ramtek, which was undoubtedly an ancient holy place dating back at least to the time of the Vakatakas. There is a broken image of Nandi lying in front of the present temple. Though the present structure cannot date back to the fourth century A.C., to which period the inscription can be referred, it undoubtedly marks an ancient site and may have been erected when the original temple fell into ruins.

The inscription is not dated. The name of the king’s family which occurred in the beginning of the fourth line has, unfortunately, been lost ; but on the evidence of palaeography Cunningham conjecturally assigned the record to Rudrasena I, though according to the notions then prevalent, he called him a king of Kailakila Yavanas, and placed him in 170 A.C.2 Though this date cannot now be accepted, Cunningham’s attribution of the present record to the Vakataka king Rudrasena I seems to be correct. There were two kings of this name in the dynasty of the Vakatakas, viz-, Rudrasena I, who was the grandson and successor of Pravarasena I, and Rudrasena II, the grandson of the former and son-in-law of Chandragupta II-Vikramaditya. Of these, the former was a Shaiva, being a fervent devotee of Svami-Mahabhairava,3 while the latter, probably owing to the influence of his wife Prabhavatigupta, was a worshipper of Chakrapani (Vishnu)4. As the present inscription evidently records the building of a Shiva temple, it may be ascribed to Rudrasena I. This is also confirmed by the palaeographic evidence detailed above5.

The importance of the present inscription lies in this that it is the earliest record of the Vakatakas discovered so far, and is, besides, the only lithic record of that royal family. Its situation shows that Rudrasena I ruled south of the Narmada and renders doubtful the identification of Rudradeva, who is mentioned in the Allahabad stone pillar inscription as one of the kings of Aryavarta, with Rudrasena I of the Vakataka dynasty.

There remains now the question — Why was the inscription inscribed breadthwise and commenced at the narrow end of the slab? As is well-known, there was a revival of Hinduism and Sanskrit learning in the age of the Vakatakas. They themselves performed animal sacrifices, and could have therefore had no regard for Asoka’s precepts of ahimsā. When therefore Rudrasena I built a temple of his favourite deity and wanted to put up an inscription of his own to record it, he could have felt no scruples in chiselling off some part of the earlier inscription to make room for his record. The stone was probably placed

1. C.A.S.R., Vol. VII, pp. 125-26

2. Ibid., Vol. I, p. 29.

3. See the adjective अत्यंतस्वमिमहाभैरवभक्तस्य applied to him in the copper-plates of Pravarasena II.

4. See his description भागवतश्चक्रपाणेxप्रसादोपार्जितश्रीसमुदयस्य in the copper-plates of his son Pravarasena II.

5. Note especially the unlooped n in line 6. This letter has a looped form in all other Vakataka inscriptions.

[p.4]: on the broader end of its length and half-buried, leaving only the Vakataka record above the ground. The left-hand portion of the earlier record was left untouched as the Vakataka inscription, which was commenced at the narrow end of the slab, was finished about the middle of the stone.

There is only one place, viz-, Chikkamburi,1 mentioned in both the records. As pointed out by Hiralal, it is identical with the adjoining village Chikmara. Chikkamburi seems to have been a flourishing city for more than six hundred years ; for, both the Mahāmātra of Asoka and the Vakataka king Rudrasena I thought it fit to incise their records there. In ancient times it must have extended to and perhaps included in its expanse the site of the modern village Deotek where the inscribed slab was lying.

1 चिकम्बु(रि)...स...

2 ...(स ?) ज ...

3 प्रवरम...मस्यायं

4 ...वंश (जा*)तस्येदं रुद्र-

5. सेनरा[ज्ञ:][स्व*]2धर्म्मस्थानं (नम् ।) [।]

(At) Chikkamburi...

Pravara3

(Line 4) This (is) a special place of religious worship of Rājan Rudrasena (I), born in the family (of the Vakatakas).1. The name appears as Chikambar[i] in the earlier inscription.

2. Read रुद्रसेनराजस्य

3. This may refer to Pravarasena I.

WIKI Editor Notes

- Naga (Jat clan) → Nagbhir (नागभीड़) is a town and tahsil in Chandrapur district in Maharashtra.

देवटेक

विजयेन्द्र कुमार माथुर[4] ने लेख किया है ...देवटेक (AS, p.447) जिला चांदा महाराष्ट्र से हाल ही में एक अशोक कालीन ब्राह्मी अभिलेख प्राप्त हुआ है. अशोक मौर्य का समय 300-332 ईसा पूर्व है.