Gridhrakuta

| Author:Laxman Burdak, IFS (R) |

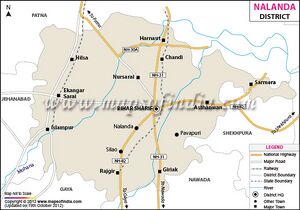

Gridhrakuta (गृध्रकूट) is one of several sites frequented by the Buddha and his community of disciples for both training and retreat. It is the second "holiest" place of Buddhism, after the Maha Bodhi Temple. It is called Gijjhakuta in Pali and is located about 5 kms south-east of the town of Rajgir in Nalanda district of Bihar, India. It is a popular destination for both local tourists and Buddhist pilgrims from overseas.

Variants

- Gijjhakuta (गिज्झकूट) = Gridhrakuta गृध्रकूट (AS, p.284)

- Gridhrakuta (गृध्रकूट) (AS, p.294)

- Vulture Peak Mountain

- Vulture Peak

- Gijjhakuto

History

Its location is frequently mentioned in the Buddhist sutras both in the Theravada Pali Canon[1] [2]and in the Mahayana sutras, as where the Buddha gave a particular sermon. Among the latter are the Heart Sutra, the Lotus Sutra and the Suramgamasamadhi sutra, as well as many other Prajnaparamita Sutras.

It is explicitly mentioned in the Lotus Sutra in Chapter 16 as the Buddha's "Pure Land":[3]

Mahayana (major branch of Buddhism) mentions — Ratnakara in Mahayana glossary: Ratnākara (रत्नाकर) is one of the Bodhisattvas accompanying the Buddha at Rājagṛha on the Gṛdhrakūṭaparvata, mentioned in a list of twenty-two in to Mahāprajñāpāramitāśāstra chapter 13.—They were at the head of countless thousands of koṭinayuta of Bodhisattva-mahāsattvas who were all still awaiting succession and will still accede to Buddhahood. He is also known as La na kie lo or Pai tsi.

Ratnākara is one of the sixteen classified as a lay (gṛhastha) Bodhisattva: Ratnākara, a young prince (kumāra), lives in Vaiśālī.[4][5]

Alexander Cunningham

Alexander Cunningham[6] mentions.... Kusagarapura was the original capital of Magadha, which was called Rajagriha, or the " Royal Residence." It was also named Girivraja, or the "hill-surrounded," which agrees with Hwen Thsang's description of it as a town " surrounded by mountains." Girivraja[7] is the name given in both the Ramayana and the Mahabharata to the old capital of Jarasandha, king of Magadha, who was one of the principal actors in the Great War, about 1426 B.C. The Chinese pilgrim Fa-Hian[8] describes the city as situated in a valley between five hills, at 4 li, or two-thirds of a mile, to the south of the new town of Rajagriha. The same position and about the same distance are given by Hwen Thsang, who also mentions some hot springs, which still exist. Fa-Hian

[p.463]: further states that the " five hills form a girdle like the walls of a town," which is an exact description of Old Rajagriha, or Purana Rajgir, as it is now called by the people.

A similar description is given by Tumour from the Pali annals of Ceylon, where the five hills are named Gijjhakuto, Isigili, Webharo, Wepullo, and Pandawo[9]

In the Mahabharata the five hills are named Vaihara, Varaha, Vrishabha, Rishi-giri, and Chaityaka;[10] but at present they are called Baibhar-giri, Vipula-giri, Ratna-giri, Udaya-giri, and Sona-giri.

In the inscriptions of the Jain temples on Mount Baibhar, the name is sometimes written Baibhara, and sometimes Vyavahara. It is beyond all doubt the Webharo Mountain of the Pali annals, on whose side was situated the far-famed Sattapanni Cave, in front of which was held the first Buddhist synod, in 543 B.C. This cave, I believe, still exists under the name of Son Bhandar, or " Treasury of gold," in the southern face of the mountain ; but following Hwen Thsang's description, it should rather be looked for in the northern face. In the Tibetan Dulva it is called the " Cave of the Nyagrodha" or Banian-tree.[11]

Ratnagiri is due east, one mile distant from the Son Bhandar Cave. This situation corresponds exactly with Fa-Hian's position of the Pippal-tree Cave, in which Buddha after his meals was accustomed to meditate.

Gijjhakuta or Vulture Peak

The Gijjhakuta, the Vulture Peak, was the Buddha’s favorite retreat in Rajagaha and the scene for many of his discourses. According to the commentaries this place got its name because vultures used to perch on some of the peak’s rocks.

The several rock shelters around the Gijjhakuta, its fine view across the valley, and its peaceful environment made it the perfect place for meditation. Climbing the steps that lead to the top, the pilgrim passes a large cave. This is the Sukarakhata (the Boar’s Grotto) where the Buddha delivered two discourses, the Discourse to Long Nails and the Sukarakhata Sutta.

It was here too that Sariputta attained enlightenment. The Sukarakhata seems to have been formed by excavating the earth from under the huge rock that forms the grotto's roof, an impression confirmed by legend. According to the Pali commentaries during the time of Kassapa Buddha a boar rooting around under the rock made a small cavity which was later enlarged when monsoon rains washed more earth away. Later, an ascetic discovered the cave and, deciding it would be a good place to live in, built a wall around it, furnished it with a couch, and ‘made it as clean as a golden bowl polished with sand.’

Climbing further, the pilgrim can see the ruins of stupas and the foundations of a small temple built on the summit in ancient times. When the simple and devoted Chinese pilgrim Fa Hien came here, he was deeply moved by the atmosphere on the Gijjhakuta. ‘In the new city, Fa Hien bought incense, flowers, oil and lamps and hired two monks, long residents in the place, to carry them to the peak. When he himself arrived, he made his offerings with flowers and incense and lit the lamps when the darkness began to come on. He felt melancholy but restrained his tears, and said, ‘Here the Buddha delivered the Surangama Sutra. I, Fa Hien, was born when I could not meet the Buddha and now I only see the footprints which he has left and the place where he lived and nothing more.’ With this, in front of the rock cavern, he chanted the Surangama Sutra, remaining there overnight and then returned towards the new city.’ In Dharmasvamin’s time (13th century), the Gijjhakuta was ‘the abode for numerous carnivorous animals such as tiger, black bear and brown bear,’ and in order to frighten away the animals, pilgrims visiting the Gijjhakuta would beat drums, blow conches and carry tubes of green bamboo that would emit sparks. A Buddha statue, dating from the 6th century CE, found on the Gijjhakuta, is now housed in the Archaeological Museum at Nalanda. The Gijjhakuta is located about 5 kilometers south-east of the town of Rajgir and is a popular destination for both local tourists and Buddhist pilgrims form overseas. Because the Sadharmapundrika Sutra (Lotus Sutra) was taught on the Gijjhakuta, the place is particularly popular with Japanese and Korean pilgrims.

Vulture Peak may be the second "holiest" place of Buddhism, after the Maha Bodhi Temple because this is the place where the Buddha spent so much time on retreat, meditating, and teaching so many discourses. Many Buddhists prefer to take the climb up on foot to take the same steps as the Buddha and his closest disciples.

It is also very close to the location of the First Buddhist council at Rajagaha. The Triple Gem is fully represented at Vulture Peak by the fact that Buddha spent so much time there, also teaching Dhamma and the other Sangha members going there for instruction, to teach, to meditate, and to compile all of the teachings at the First Buddhist council at The Sattapanni Cave, which is about 5 km from Vulture Peak.[12]

Visit by Fahian

James Legge[13] writes that Entering the valley, and keeping along the mountains on the south-east, after ascending fifteen le, (the travellers) came to mount Gridhra-kuta.1 Three le before you reach the top, there is a cavern in the rocks, facing the south, in which Buddha sat in meditation. Thirty paces to the north-west there is another, where Ananda was sitting in meditation, when the deva Mara Pisuna,2 having assumed the form of a large vulture, took his place in front of the cavern, and frightened the disciple. Then Buddha, by his mysterious, supernatural power, made a cleft in the rock, introduced his hand, and stroked Ananda’s shoulder, so that his fear immediately passed away. The footprints of the bird and the cleft for (Buddha’s) hand are still there, and hence comes the name of “The Hill of the Vulture Cavern.”

In front of the cavern there are the places where the four Buddhas sat. There are caverns also of the Arhats, one where each sat and meditated, amounting to several hundred in all. At the place where in front of his rocky apartment Buddha was walking from east to west (in meditation), and Devadatta, from among the beetling cliffs on the north of the mountain, threw a rock across, and hurt Buddha’s toes,3 the rock is still there.4

The hall where Buddha preached his Law has been destroyed, and only the foundations of the brick walls remain. On this hill the peak is beautifully green, and rises grandly up; it is the highest of all the five hills. In the New City Fa-hien bought incense-(sticks), flowers, oil and lamps, and hired two bhikshus, long resident (at the place), to carry them (to the peak). When he himself got to it, he made his offerings with the flowers and incense, and lighted the lamps when the darkness began to come on. He felt melancholy, but restrained his tears and said, “Here Buddha delivered the Surangama (Sutra).5 I, Fa-hien, was born when I could not meet with Buddha; and now I only see the footprints which he has left, and the place where he lived, and nothing more.” With this, in front of the rock cavern, he chanted the Surangama Sutra, remained there over the night, and then returned towards the New City.6

1 See chap. xxviii, note 1.

2 See chap. xxv, note 9. Pisuna is a name given to Mara, and signifies “sinful lust.”

3 See M. B., p. 320. Hardy says that Devadatta’s attempt was “by the help of a machine;” but the oldest account in the Sacred Books of the East, vol. xx, Vinaya Texts, p. 245, agrees with what Fa-hien implies that he threw the rock with his own arm.

4 And, as described by Hsuan-chwang, fourteen or fifteen cubits high, and thirty paces round.

5 See Mr. Bunyiu Nanjio’s “Catalogue of the Chinese Translation of the Buddhist Tripitaka,” Sutra Pitaka, Nos. 399, 446. It was the former of these that came on this occasion to the thoughts and memory of Fa-hien.

6 In a note (p. lx) to his revised version of our author, Mr. Beal says, “There is a full account of this perilous visit of Fa-hien, and how he was attacked by tigers, in the ‘History of the High Priests.’” But “the high priests” merely means distinguished monks, “eminent monks,” as Mr. Nanjio exactly renders the adjectival character. Nor was Fa-hien “attacked by tigers” on the peak. No “tigers” appear in the Memoir. “Two black lions” indeed crouched before him for a time this night, “licking their lips and waving their tails;” but their appearance was to “try,” and not to attack him; and when they saw him resolute, they “drooped their heads, put down their tails, and prostrated themselves before him.” This of course is not an historical account, but a legendary tribute to his bold perseverance.

गृध्रकूट

विजयेन्द्र कुमार माथुर[14] ने लेख किया है ...गृध्रकूट (p.294) राजगृह (बिहार) के निकट एक पर्वत का नाम है, जिसकी गुफ़ा में गौतम बुद्ध वर्षा काल व्यतीत किया करते थे। इस पहाड़ी पर अनेक रहने के स्थान आज भी बने हुए हैं। यह पर्वत राजगृह की पाँच पहाड़ियों में से है, जिनका नामोल्लेख पाली ग्रन्थों में है। गृध्रकूट को पाली भाषा में 'गिज्ज्ञकूट' कहा गया है। एक पाली ग्रन्थ में बुद्ध ने राजगृह के जिन स्थानों को सुन्दर तथा सुखदायक बताया है, उनमें गृध्रकूट भी है। महाभारत में राजगृह की जिन पाँच पहाड़ियों का नाम है, उनमें गृध्रकूट का नाम नहीं है। (दे. राजगृह)

References

- ↑ "The Sona Sutta: About Sonal

- ↑ The Daruka-Khanda Sutta: The Woodpile

- ↑ Vakkali Sutta of the Pali Canon

- ↑ Source: Wisdom Library: Maha Prajnaparamita Sastra

- ↑ https://www.wisdomlib.org/definition/ratnakara

- ↑ Alexander Cunningham: The Ancient Geography of India/Magadha , pp.462-

- ↑ Lassen, Ind. Alterthum, i. 604.

- ↑ Beal's 'Fah-Hian,' c. xxviii. 112.

- ↑ Journ. Asiat. Soc. Bengal 1838, p. 996.

- ↑ Lassen, Ind. Alterthum, ii. 79. The five hills are all shown in Map No. XII.

- ↑ Csoma de Koros in Bengal ' Asiatic Researches,' xx. 91.

- ↑ Vulture_Peak on dhammawiki

- ↑ A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms/Chapter 29

- ↑ Aitihasik Sthanavali by Vijayendra Kumar Mathur, p.294