Orkney

| Author:Laxman Burdak, IFS (Retd.) |

Orkney /ˈɔːrkni/ (Scots: Orkney), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago in the Northern Isles of Scotland situated off the north coast of Great Britain. Orkney contains some of the oldest and best-preserved Neolithic sites in Europe, and the "Heart of Neolithic Orkney" is a designated UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Location

Orkney Islands archipelago is situated in the Northern Isles of Scotland situated off the north coast of Great Britain. Orkney is 16 km north of the coast of Caithness and comprises approximately 70 islands, of which 20 are inhabited.[1][2]

Variants

Origin of name

Orkney seems to be derived from Sanskrit word Vārkeṇya. V. S. Agrawala[3] mentions the names of Ayudhjivi Sanghas in the Panini's Sutras which include Vṛika (V.3.115) : An individual member of this Sangha was called Vārkeṇya, and the whole Sangha Vrika. This name standing alone in the Sutra with a suffix peculiar from the rest is hitherto untraced. It is stated to be Ayudhajivin, but not necessarily associated with Vahika. It should probably be identified with Varkaṇa, the old Persian form in the Behistun inscription of Darius, mentioned along with Pārthava or the Parthians (Behistun inscription Col. II.1.16). There is a striking similarity between the Sanskrit and old Persian forms of the name, e.g. Vārkeṇya equal to Vārkaṇa in the singular number , and Vrikah equal to Varkā in plural as in the expression Sakā Hauma-Varkā.

This origin gets support from the fact that the bones of pig of date c. 3600 BC were found in coast of Papa Westray. Thet name of Orkney derives from these aggressive creatures. It was first recorded in c.320BC by Pytheas when he wrote of his visit to Orkas, the islands of the Boar Kindred. It may have been a totem animal. [4]

Jat Gotras Namesake

- Virk = Orciani (Pliny.vi.18)

- Virk = Orchenus (Pliny.vi.30)

Mention by Pliny

Pliny [5] mentions 'Nations situated around the Hyrcanian Sea'.... Below the district inhabited by them, we find the nations of the Orciani, the Commori, the Berdrigæ, the Harmatotropi,11 the Citomaræ, the Comani, the Marucæi, and the Mandruani.

11 This appears to mean the nations of "Chariot horse-breeders."

Mention by Pliny

Pliny[6] mentions Mesopotamia .... Hipparenum24, rendered famous, like Babylon, by the learning of the Chaldæi, and situate near the river Narraga25, which falls into the Narroga, from which a city so called has taken its name. The Persæ destroyed the walls of Hipparenum. Orchenus also, a third place of learning of the Chaldæi, is situate in the same district, towards the south; after which come the Notitæ the Orothophanitæ, and the Grecichartæ.26

24 Nothing appears to be known of this place; but Hardouin thinks that it is the same with one called Maarsares by Ptolemy, and situate on the same river Narraga.

25 Parisot says that this river is the one set down in the maps as falling into the Tigris below its junction with the Euphrates, and near the mouths of the two rivers. He says that near the banks of it is marked the town of Nabrahan, the Narraga of Pliny.

26 There is great doubt as to the correct spelling of these names.

Etymology

Pytheas of Massilia visited Britain – probably sometime between 322 and 285 BCE – and described it as triangular in shape, with a northern tip called Orcas.[7] This may have referred to Dunnet Head, from which Orkney is visible.[8] Writing in the 1st century AD, the Roman geographer Pomponius Mela called the islands Orcades, as did Tacitus in 98 AD, claiming that his father-in-law Agricola had "discovered and subjugated the Orcades hitherto unknown"[9][10] (although both Mela and Pliny had previously referred to the islands.[11]) Etymologists usually interpret the element orc- as a Pictish tribal name meaning "young pig" or "young boar".[12] Speakers of Old Irish referred to the islands as Insi Orc "island of the pigs".[13][14] The archipelago is known as Ynysoedd Erch in modern Welsh and Arcaibh in modern Scottish Gaelic, the -aibh representing a fossilized prepositional case ending.

The Anglo-Saxon monk Bede refers to the islands as Orcades insulae in his seminal work Ecclesiastical History of the English People.[15]

Norwegian settlers arriving from the late ninth century reinterpreted orc as the Old Norse orkn "seal" and added eyjar "islands" to the end[16] so the name became Orkneyjar "Seal Islands". The plural suffix -jar was later removed in English leaving the modern name "Orkney". According to the Historia Norwegiæ, Orkney was named after an earl called Orkan.[17]

The Norse knew Mainland Orkney as Megenland "Mainland" or as Hrossey "Horse Island".[18] The island is sometimes referred to as Pomona (or Pomonia), a name that stems from a sixteenth-century mistranslation by George Buchanan, which has rarely been used locally.[19][20]

History

A form of the name dates to the pre-Roman era and the islands have been inhabited for at least 8,500 years, originally occupied by Mesolithic and Neolithic tribes and then by the Picts. Orkney was invaded and forcibly annexed by Norway in 875 and settled by the Norse. The Scottish Parliament then re-annexed the earldom to the Scottish Crown in 1472, following the failed payment of a dowry for James III's bride Margaret of Denmark.[21]Orkney contains some of the oldest and best-preserved Neolithic sites in Europe, and the "Heart of Neolithic Orkney" is a designated UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Alistair Moffat[22] notes...Colder and wetter weather in Shetland, Orkney and Hebrides encouraged the spread of peat and in some places the new field boundaries set up by bronze age farmers were submerged across the span of only a few generations. Upland cultivation gave way to stock-rearing and the population dwindled. Some historians believe that the eruption of Hekla triggered a migration from North Western Scotland to the east but at present there exists no firm DNA evidence to support this. The deferences as detected in the east-west frequencies of the subgroups of R1b appear already to have been establishing themselves.

Pre-History

A charred hazelnut shell, recovered in 2007 during excavations in Tankerness on the Mainland has been dated to 6820–6660 BC indicating the presence of Mesolithic nomadic tribes.[23] The earliest known permanent settlement is at Knap of Howar, a Neolithic farmstead on the island of Papa Westray, which dates from 3500 BC. The village of Skara Brae, Europe's best-preserved Neolithic settlement, is believed to have been inhabited from around 3100 BC.[24] Other remains from that era include the Standing Stones of Stenness, the Maeshowe passage grave, the Ring of Brodgar and other standing stones. Many of the Neolithic settlements were abandoned around 2500 BC, possibly due to changes in the climate.[25][26][27]

During the Bronze Age fewer large stone structures were built although the great ceremonial circles continued in use[28] as metalworking was slowly introduced to Britain from Europe over a lengthy period.[29][30] There are relatively few Orcadian sites dating from this era although there is the impressive Plumcake Mound near the Ring of Brodgar and various islands sites such as Tofts Ness on Sanday and the remains of two houses on Holm of Faray.[31]

Alistair Moffat[32] writes that ...In this era of migrations Orkney may not have been fought over. Before the early farmers arrived in the period before Knap of Howar was built in c3600 BC, the archipelago was probably not inhabited. Only one tiny scrap of evidence for occupation before that date has ever been found: a charred hazelnut shell at Tankerness was carbon dated to c6000 BC. And that may have been the deposit of a summer expedition from the mainland of Scotland.

If Orkney was empty, green and fertile Arcadia, that may have encouraged the precocious culture that built the temples at Ness of Brodgar and the monument around them. Other Innovations flowed South. Too heavy and fragile for the mobile Life style of the hunter-gatherers, pottery, the first man-made product in Britain, who needed by sedentary farming Communities for storage.

But it is very difficult to identify the DNA of this remarkable Society. Modern Orkney is not populated by a high percentage of men who carry G lineage – infact they are rarer than in mainland Britain. Instead, another marker from a much later period seems to have largely supplanted the DNA of their farmers. Scandinavians, the Vikings, began raiding at the end of the 8th century AD and when they settled Orkney, they seem to have carried out a similarly brutal removal of the natives as happened across the rest of Britain c4000 BC.

Iron Age

Excavations at Quanterness on the Mainland have revealed an Atlantic roundhouse built about 700 BC and similar finds have been made at Bu on the Mainland and Pierowall Quarry on Westray.[33] The most impressive Iron Age structures of Orkney are the ruins of later round towers called "brochs" and their associated settlements such as the Broch of Burroughston[34] and Broch of Gurness. The nature and origin of these buildings is a subject of ongoing debate. Other structures from this period include underground storehouses, and aisled roundhouses, the latter usually in association with earlier broch sites.[35]

During the Roman invasion of Britain the "King of Orkney" was one of 11 British leaders who is said to have submitted to the Emperor Claudius in AD 43 at Colchester.[36] After the Agricolan fleet had come and gone, possibly anchoring at Shapinsay, direct Roman influence seems to have been limited to trade rather than conquest.[37]

By the late Iron Age, Orkney was part of the Pictish kingdom, and although the archaeological remains from this period are less impressive there is every reason to suppose the fertile soils and rich seas of Orkney provided the Picts with a comfortable living.[38] The Dalriadic Gaels began to influence the islands towards the close of the Pictish era, perhaps principally through the role of Celtic missionaries, as evidenced by several islands bearing the epithet "Papa" in commemoration of these preachers.[39] However, before the Gaelic presence could establish itself the Picts were gradually dispossessed by the Norse from the late 8th century onwards. The nature of this transition is controversial, and theories range from peaceful integration to enslavement and genocide.[40] It has been suggested that an assault by forces from Fortriu in 681 in which Orkney was "annihilated" may have led to a weakening of the local power base and helped the Norse come to prominence.[41]

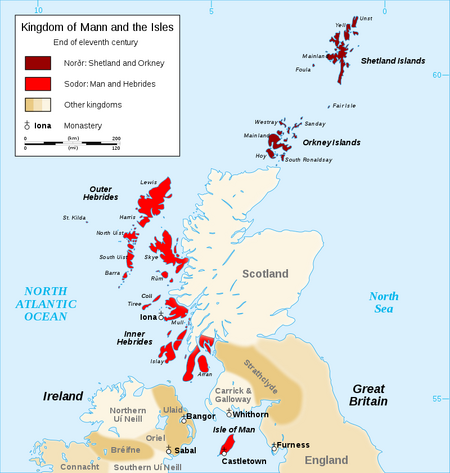

Norwegian rule

Both Orkney and Shetland saw a significant influx of Norwegian settlers during the late 8th and early 9th centuries. Vikings made the islands the headquarters of their pirate expeditions carried out against Norway and the coasts of mainland Scotland. In response, Norwegian king Harald Fairhair (Harald Hårfagre) annexed the Northern Isles, comprising Orkney and Shetland, in 875. [42] Rognvald Eysteinsson received Orkney and Shetland from Harald as an earldom as reparation for the death of his son in battle in Scotland, and then passed the earldom on to his brother Sigurd the Mighty.[43]

However, Sigurd's line barely survived him and it was Torf-Einarr, Rognvald's son by a slave, who founded a dynasty that controlled the islands for centuries after his death.[44] He was succeeded by his son Thorfinn Skull-splitter and during this time the deposed Norwegian King Eric Bloodaxe often used Orkney as a raiding base before being killed in 954. Thorfinn's death and presumed burial at the broch of Hoxa, on South Ronaldsay, led to a long period of dynastic strife.[45]

A group of warriors in medieval garb surround two men whose postures suggest they are about to embrace. The man on the right is taller, has long fair hair and wears a bright red tunic. The man on the left his balding with short grey hair and a white beard. He wears a long brown cloak. Artist's conception of King Olaf Tryggvason of Norway, who forcibly Christianised Orkney.[46]

Initially a pagan culture, detailed information about the turn to the Christian religion to the islands of Scotland during the Norse-era is elusive.[47] The Orkneyinga Saga suggests the islands were Christianised by Olaf Tryggvasson in 995 when he stopped at South Walls on his way from Ireland to Norway. The King summoned the jarl Sigurd the Stout and said, "I order you and all your subjects to be baptised. If you refuse, I'll have you killed on the spot and I swear I will ravage every island with fire and steel." Unsurprisingly, Sigurd agreed and the islands became Christian at a stroke,[48] receiving their own bishop in the early 11th century.

Thorfinn the Mighty was a son of Sigurd and a grandson of King Máel Coluim mac Cináeda (Malcolm II of Scotland). Along with Sigurd's other sons he ruled Orkney during the first half of the 11th century and extended his authority over a small maritime empire stretching from Dublin to Shetland. Thorfinn died around 1065 and his sons Paul and Erlend succeeded him, fighting at the Battle of Stamford Bridge in 1066.[49] Paul and Erlend quarreled as adults and this dispute carried on to the next generation. The martyrdom of Magnus Erlendsson, who was killed in April 1116 by his cousin Haakon Paulsson, resulted in the building of St. Magnus Cathedral, still today a dominating feature of Kirkwall.

Unusually, from c. 1100 onwards the Norse jarls owed allegiance both to Norway for Orkney and to the Scottish crown through their holdings as Earls of Caithness.[50] In 1231 the line of Norse earls, unbroken since Rognvald, ended with Jon Haraldsson's murder in Thurso.[51] The Earldom of Caithness was granted to Magnus, second son of the Earl of Angus, whom Haakon IV of Norway confirmed as Earl of Orkney in 1236.[52] In 1290, the death of the child princess Margaret, Maid of Norway in Orkney, en route to mainland Scotland, created a disputed succession that led to the Wars of Scottish Independence.[53] In 1379 the earldom passed to the Sinclair family, who were also barons of Roslin near Edinburgh.[54]

Evidence of the Viking presence is widespread, and includes the settlement at the Brough of Birsay,[55] the vast majority of place names,[56] and the runic inscriptions at Maeshowe.

Annexation by Scotland

In 1468 Orkney was pledged by Christian I, in his capacity as King of Norway, as security against the payment of the dowry of his daughter Margaret, betrothed to James III of Scotland. However the money was never paid, and Orkney was annexed by the Kingdom of Scotland in 1472.

The history of Orkney prior to this time is largely the history of the ruling aristocracy. From now on the ordinary people emerge with greater clarity. An influx of Scottish entrepreneurs helped to create a diverse and independent community that included farmers, fishermen and merchants that called themselves comunitas Orcadie and who proved themselves increasingly able to defend their rights against their feudal overlords.[57]

From at least the 16th century, boats from mainland Scotland and the Netherlands dominated the local herring fishery. There is little evidence of an Orcadian fleet until the 19th century but it grew rapidly and 700 boats were involved by the 1840s with Stronsay and later Stromness becoming leading centres of development. White fish never became as dominant as in other Scottish ports.[58]

In the 17th century, Orcadians formed the overwhelming majority of employees of the Hudson's Bay Company in Canada. The harsh climate of Orkney and the Orcadian reputation for sobriety and their boat handling skills made them ideal candidates for the rigours of the Canadian north.[59]

Agricultural improvements beginning in the 17th century resulted in the enclosure of the commons and ultimately in the Victoria era the emergence of large and well-managed farms using a five-shift rotation system and producing high-quality beef cattle.[60]

During the 18th century Jacobite risings, Orkney was largely Jacobite in its sympathies. At the end of the 1715 rebellion, a large number of Jacobites who had fled north from mainland Scotland sought refuge on Orkney and were helped on to safety in Sweden.[61] In 1745, the Jacobite lairds on the islands ensured that Orkney remained pro-Jacobite in outlook, and was a safe place to land supplies from Spain to aid their cause. Orkney was the last place in the British Isles that held out for the Jacobites and was not retaken by the British Government until 24 May 1746, over a month after the defeat of the main Jacobite army at Culloden.[62]

Related sites in Orkney

A comparable, though smaller, site exists at Rinyo on Rousay. Unusually, no Maeshowe-type tombs have been found on Rousay and although there are a large number of Orkney–Cromarty chambered cairns, these were built by Unstan ware people.

Knap of Howar, on the Orkney island of Papa Westray, is a well-preserved Neolithic farmstead. Dating from 3500 BC to 3100 BC, it is similar in design to Skara Brae, but from an earlier period, and it is thought to be the oldest preserved standing building in northern Europe.[63]

There is also a site currently under excavation at Links of Noltland on Westray that appears to have similarities to Skara Brae.[64]

World Heritage status

"The Heart of Neolithic Orkney" was inscribed as a World Heritage site in December 1999. In addition to Skara Brae the site includes Maeshowe, the Ring of Brodgar, the Standing Stones of Stenness and other nearby sites. It is managed by Historic Scotland, whose "Statement of Significance" for the site begins:

- The monuments at the heart of Neolithic Orkney and Skara Brae proclaim the triumphs of the human spirit in early ages and isolated places. They were approximately contemporary with the mastabas of the archaic period of Egypt (first and second dynasties), the brick temples of Sumeria, and the first cities of the Harappa culture in India, and a century or two earlier than the Golden Age of China. Unusually fine for their early date, and with a remarkably rich survival of evidence, these sites stand as a visible symbol of the achievements of early peoples away from the traditional centres of civilisation.[65]

Odin-Stone: Traditions and history

- Let us imagine, then, families approaching Stenness at the appointed time of year, men, women and children, carrying bundles of bones collected together from the skeletons of disinterred corpses–skulls, mandibles, long bones–carrying also the skulls of totem animals, herding a beast that was one of several to be slaughtered for the feasting that would accompany the ceremonies..... — Aubrey Burl, Rites of the Gods, 1981.[66]

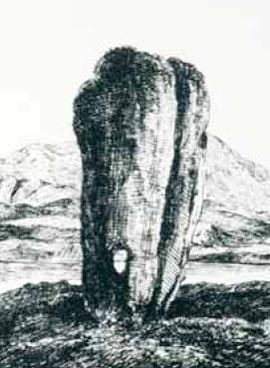

Even in the 18th century the site was still associated with traditions and rituals, by then relating to Norse gods. It was visited by Walter Scott in 1814. Other antiquarians documented the stones and recorded local traditions and beliefs about them. One stone, known as the "Odin Stone" which stood in the field to the north of the henge,[67] was pierced with a circular hole, and was used by local couples for plighting engagements by holding hands through the gap. It was also associated with other ceremonies and believed to have magical power.[68] There was a reported tradition of making all kinds of oaths or promises with one's hand in the Odin Stone; this was known as taking the "Vow of Odin".[69]

In December 1814 Captain W. Mackay, a recent immigrant to Orkney who owned farmland in the vicinity of the stones, decided to remove them on the grounds that local people were trespassing and disturbing his land by using the stones in rituals. He started in December 1814 by smashing the Odin Stone. This caused outrage and he was stopped after destroying one other stone and toppling another.[70]

The toppled stone was re-erected in 1906 along with some inaccurate reconstruction inside the circle.[71]

In the 1970s, a dolmen structure was toppled, since there were doubts as to its authenticity. The two upright stones remain in place.[72]

A picture of the Stones of Stenness features on the cover of Van Morrison's album The Philosopher's Stone, and the Odin stone is depicted on Julian Cope's album Discover Odin.

See also

- Gurg (गुर्ग) is an ancient historical place in Adilabad district of Telangana, India. It is known for prehistoric monuments of stone circles similar to those in Stonehenge in Britain. [73]

External links

Gallery

-

Location of Orkney

-

Orkney on map of Scotland

References

- ↑ Haswell-Smith, Hamish (2004). The Scottish Islands. Edinburgh: Canongate. ISBN 978-1-84195-454-7. pp. 336–403.

- ↑ National Records of Scotland (15 August 2013) (pdf) Statistical Bulletin: 2011 Census: First Results on Population and Household Estimates for Scotland - Release 1C (Part Two). "Appendix 2: Population and households on Scotland’s inhabited islands".

- ↑ V. S. Agrawala: India as Known to Panini, 1953, p.443

- ↑ Alistair Moffat: The British: A Genetic Journey, Birlinn, 2013,ISBN:9781780270753, p.78

- ↑ Natural History by Pliny Book VI/Chapter 18

- ↑ Natural History by Pliny Book VI/Chapter 30

- ↑ Breeze, David J. "The ancient geography of Scotland" in Smith and Banks (2002) pp. 11–13.

- ↑ "Early Historical References to Orkney" Orkneyjar.com.

- ↑ "Early Historical References to Orkney" Orkneyjar.com.

- ↑ Tacitus (c. 98) Agricola. Chapter 10. "ac simul incognitas ad id tempus insulas, quas Orcadas vocant, invenit domuitque".

- ↑ Breeze, David J. "The ancient geography of Scotland" in Smith and Banks (2002) pp. 11–13.

- ↑ Waugh, Doreen J. "Orkney Place-names" in Omand (2003) p. 116.

- ↑ Pokorny, Julius (1959) Indogermanisches etymologisches Wörterbuch.

- ↑ "The Origin of Orkney" Orkneyjar.com.

- ↑ Plummer, Carolus (2003). Venerabilis Baedae Historiam Ecclesiasticam (Ecclesiastical History of Bede. Gorgias Press. ISBN 978-1-59333-028-6.

- ↑ Thomson (2008) p. 42.

- ↑ "A History of Norway", vol. XIII Translated by Devra Kunin pp. 7–8

- ↑ Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 354.

- ↑ Buchanan, George (1582) Rerum Scoticarum Historia: The First Book The University of California, Irvine. Revised 8 March 2003

- ↑ "Pomona or Mainland?" Orkneyjar.com.

- ↑ Thomson, William P.L. (2008) The New History of Orkney. Edinburgh. Birlinn. ISBN 978-1-84158-696-0, p. 220.

- ↑ Alistair Moffat: The British: A Genetic Journey, Birlinn, 2013,ISBN:9781780270753, p.124-125

- ↑ "Hazelnut shell pushes back date of Orcadian site" (3 November 2007) Stone Pages Archaeo News.

- ↑ "Skara Brae Prehistoric Village" Historic Scotland.

- ↑ Moffat, Alistair (2005) Before Scotland: The Story of Scotland Before History. London. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0500051337, p. 154.

- ↑ "Scotland: 2200–800 BC Bronze Age" Archived 3 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine. worldtimelines.org.uk

- ↑ Ritchie, Graham "The Early Peoples" in Omand (2003) pp. 32, 34.

- ↑ Wickham-Jones (2007) p. 73.

- ↑ Moffat (2005) pp. 154, 158, 161.

- ↑ Whittington, Graeme and Edwards, Kevin J. (1994) "Palynology as a predictive tool in archaeology" (pdf) Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 124 pp. 55–65.

- ↑ 1. Wickham-Jones (2007) pp. 74–76. 2. Ritchie, Graham "The Early Peoples" in Omand (2003) p. 33.

- ↑ Alistair Moffat: The British: A Genetic Journey, Birlinn, 2013,ISBN:9781780270753, p.89-90

- ↑ Wickham-Jones (2007) pp. 81–84.

- ↑ Hogan, C. Michael (2007) Burroughston Broch. The Megalithic Portal.

- ↑ 1. Ritchie, Graham "The Early Peoples" in Omand (2003) pp. 35–37. 2. Crawford, Iain "The wheelhouse" in Smith and Banks (2002) pp. 118–22.

- ↑ Moffat (2005) pp. 173–75.

- ↑ Thomson (2008) pp. 4–5

- ↑ Thomson (2008) pp. 4–6.

- ↑ Ritchie, Anna "The Picts" in Omand (2003) pp. 42–46.

- ↑ Thomson (2008) pp. 43–50.

- ↑ Fraser (2009) p. 345

- ↑ Thomson (2008) pp. 24–27.

- ↑ Thomson (2008) p. 24.

- ↑ Thomson (2008) p. 29.

- ↑ 1. Wenham, Sheena "The South Isles" in Omand (2003) p. 211. 2. Thomson (2008) pp. 56–58.

- ↑ Thomson (2008) p. 69. quoting the Orkneyinga Saga chapter 12.

- ↑ Abrams, Lesley "Conversion and the Church in the Hebrides in the Viking Age: "A Very Difficult Thing Indeed" in Ballin Smith et al (2007) pp. 169–89

- ↑ Thomson (2008) p. 69. quoting the Orkneyinga Saga chapter 12.

- ↑ Crawford, Barbara E. "Orkney in the Middle Ages" in Omand (2003) pp. 66–68.

- ↑ Crawford, Barbara E. "Orkney in the Middle Ages" in Omand (2003) p. 64.

- ↑ Crawford, Barbara E. "Orkney in the Middle Ages" in Omand (2003) pp. 72–73.

- ↑ Thomson (2008) pp. 134–37.

- ↑ Thompson (2008) pp. 146–47.

- ↑ Thompson (2008) p. 160.

- ↑ Armit (2006) pp. 173–76.

- ↑ Thomson (2008) p. 40.

- ↑ 1. Thompson (2008) p. 183. 2. Crawford, Barbara E. "Orkney in the Middle Ages" in Omand (2003) pp. 78–79.

- ↑ Coull, James "Fishing" in Omand (2003) pp. 144–55.

- ↑ Thompson (2008) pp. 371–72.

- ↑ Thomson, William P.L. "Agricultural Improvement" in Omand (2003) pp. 93, 99.

- ↑ Baynes (1970) p. 182

- ↑ Duffy (2003) pp. 464–465, 528, 533–534, 550

- ↑ "The Knap o' Howar, Papay". Orkneyjar.

- ↑ Darvill, Timothy (1987). Prehistoric Britain. London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-03951-4.p. 105

- ↑ "The Heart of Neolithic Orkney". Historic Scotland. Archived from the original on 11 September 2007.

- ↑ Orkneyjar – The Odin Stone

- ↑ Wickham-Jones, Caroline (2012). Monuments of Orkney. Historic Scotland. ISBN 978-1-84917-073-4.

- ↑ Orkneyjar – The Odin Stone

- ↑ Wade, Z. E. A. (1895). Pixy-led in North Devon: Old Facts and New Fancies. Devon: Marshall Bros. p. 223.

- ↑ Alistair Moffat: The British: A Genetic Journey, Birlinn, 2013, ISBN:9781780270753,p.75

- ↑ Orkneyjar - The Standing Stones of Stenness

- ↑ "Stones Of Stenness Circle And Henge". Historic Scotland.

- ↑ Aitihasik Sthanavali by Vijayendra Kumar Mathur, p.292