VIII. The Resistance to the Macedonian Invasion

| Wikifier:Laxman Burdak, IFS (R) |

Battle record

| Date | War | Action | Opponent/s | Type | Country | Rank | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| May 327 – March 326 BC | Indian Campaign | Cophen Campaign | Aspasians | Expedition | present-day Afghanistan and Pakistan | King | Victory

|

| April 326 BC | Indian Campaign | Siege of Aornos | Aśvaka | Siege | present-day Pakistan | King | Victory

|

| May 326 BC | Indian Campaign | Battle of the Hydaspes | Paurava | Battle | present-day Pakistan | King | Victory

|

| November 326 – February 325 BC | Indian Campaign | Siege of Multan | Malli | Siege | present-day Pakistan | King | Victory

|

Economic development

[p.71]: We have seen how a populous and urbanized society was emerging in the Panjab out of the remnants of tribal-cum-territorial groups as a result of the progress of trade, industry, and money-economy and the growth of contacts and intercourse among peoples of various parts of the world under Achaemenian rule. Strabo relates that, between the Jhelum and the Beas, there were as many as 500 cities. Arrian gives their number as 2,000, but they may have included many small towns and even villages. He states that in the kingdom of the Glaukanikoi, between the upper courses of the Jhelum, the Chenab and the Ravi, the smallest of the cities contained no less than 5,000 inhabitants while many contained upwards of 10,000. From this one can conjecture that the population of the region was over half a million.

Demographic growth was accompanied by economic development, as one can gather from the figure of the offerings, the king of eastern Gandhara, Ambhi, made to Alexander, when he arrived on the Indus. According to Arrian he presented 3,000 oxen, 10,000 sheep, 30 elephants, 700 horsemen and 200 talents of silver or 15 talents of gold equivalent to 45,00 dares or 2,25,00 dollars or 16,87,50 rupees (after devaluation) to the Macedonian invader. If eastern Gandhara alone was so rich as to afford such costly presents and the realm of Poros was so affluent as to enable him to maintain the vast army, mentioned above, one can easily have an idea of the economic potential of the rest of the Panjab at that time.

The secret of this development was the growth of commerce which presupposes peaceful conditions. The mention of Gandhari Vānija (traders of Gandhara) Kashmira-Vānija (traders of Kashmira), Madra-Vānija (traders of Madra) as illustrations of Panini’s rule Gantavya paṇyam vāyije (VI, 2, 13) shows that these people had attained proficiency in trade despite their martial nature. The Taṇḍulanāli Jataka (No. 23 of Fausboll) refers to

[p.72]: the visits of the horse-dealers of the north in the markets of Benaras and Buddhist authors mention that saffron merchants of Arachosia used to go to eastern India to sell their goods (S. Beal, Buddhist Records of the Western World, Vol. II, pp. 126-27). This advance in economic activity gave new turns to the history of the Panjab.

Transition from the tribal to the monarchical organisations

[p.72]: The aforesaid development came in the wake of the transition from the tribal oligarchies to the monarchical organisations that started in the Panjab about the foundation of the Achaemenian empire. That transition led to the growth of such unified and centralised states as those of Pukkusati and Poros, but it had not quite completed itself by the fourth century.

Hence we find Poros struggling with the oligarchical tribes of the east, on the one hand, and contending with the balkanised principalities of Gandhara, on the other. The growing might of Poros inclined the states of Gandhara to form an alliance with other big powers and drove the tribal units, like the Kshudrakas and Malavas, to pool their resources and come closer to each other. Thus the political picture of the Panjab in the latter part of the fourth century B.C. showed an inclination towards unification.

In western Gandhara rulers, like Kubhesha (in the Kabul Valley), Ashvajit (chief of the Ashvayanas, modern Pachai, or Asip or Yusufzai in the upper regions of the Kabul Valley) and Hastin (chief of the Hāstikāyanas with their seat at Pushkalavati, modern Charsadda, in the Peshawar district), and, to their north, Assakanos (chief of the Ashvakāyanas, modern Aspin of Chitral and Yashkun of Gilgit) with his capital at Mazaga (Mashakavati of Panini, Mashanagar of Babur, modern Maskhine, twenty-four miles from Bajore) were ruling independently of each other, incapable of uniting against any invader.

To the east of the Indus, in eastern Gandhara, the Ambhiyas, who had developed a school of political thought also, as we learn from the Arthashastra, had created a flourishing state. T. Ganapati Sastrin, the famous editor of the Arthashastra, suggests that Ambhi, 'The son of Ambhasor water' i. e., the Ganges, can be understood as the name of Bhisma, the celebrated hero and teacher of the Mahabharata. (Sanskrit Introduction to Vol. III of the Trivandrum edition of the Arthashstra, p. 2). Should this suggestion be correct, we would see in the Ambhiyas a school of political thought which derives its doctrine from the famous teacher Bhisma, whose views are found in some sections of the Santiparvan and also elsewhere in the

[p.73]: Mahabharata. They must have had their centre at Takshashila, modern Taxila in the Rawalpindi district, which had grown as a reputed seat of learning. Basing their policy on a sound doctrine, they developed a prosperous state between the Indus and the Jhelum, as can be gathered from the presents made by their scion Ambhi to Alexander, mentioned above. But they were bent on, preserving their independence at all costs against the expansionist ambitions of formidable neighbours and, for that purpose, did not scruple to knuckle down to a foreign invader to seek his help against them.

To the east of the Jhelum the Pauravas had established a strong kingdom ruled over by their chief Paurusha or Paurava whom the Greeks called Poros. Whereas the territory between the Jhelum and the Chenab was under his direct rule, that between the Chenab and the Ravi was placed under his nephew. The strength and power of this state can be measured by the vast army which Poros had organized and the discipline and solidarity with which it conducted itself on the field of battle.

To the north of Poros lay the realm of the king of Abhisara, comprising the Poonch, Rajori, Chibhal and Naoshera regions and encompassing almost the whole of Kashmira, as M’Crindle suggests. Its energetic king was quick in his diplomatic moves and had relations both with the Ashvakayana king of Mashakavati as well as the redoubtable Poros. Near him, in the Bhimber and Bajaur districts, to the south of Kashmira, was the flourishing kingdom of the Glausai or Glaukanikoi (Glaucukayana) with 37 big cities, the smallest containing not fewer than 5,000 inhabitants while many containing upwards of 10,000, and numerous big villages not less populous than the towns. These people maintained their independence in the face of the rising power of Poros.

To the east of the Ravi upto the Beas were the Kathaians or Kathaioi. The name of the village Kathania near Jandiala in the Amritsar district, abounding in old mounds, seems to represent their settlement. Lassen equates their name with that of Kattia, a nomadic race scattered throughout the plains. The name of the Kathiars of eastern U. P. and those, from whom Kathiawar got its name, may also be connected with them. It seems plausible to see in them a reference to the Kashas who derived their name from a school of Vedic studies founded by the pupils of Vashampayana. One of their branches, the Kapishthalas, may be identified with the Kambistholi, mentioned by Arrian, near the Ravi (M’Crindle, Megasthenes and

[p.74]: Arrian, p. 196). Their capital Sangala, situated somewhere at or near Kathania in the Amritsar district, must have been a strong centre. Quite near them were the Greeks of Sophytes (Saubhuta or Saubha) turned out from their northern seat, between the Indus and the Chenab, by the Ambhiyas or the Pauravas. There they held on to their Spartan customs and contributed some of them to their neighbours, the Kathas, also.

On the Beas, possibly between it and the Sutlej, as F. W. Thomas holds, lay the kingdom of Phegelas, (Sanskrit Bhagala), whose name seems to survive in Phagwara.

The country to the east of the Beas was exceedingly fertile, the inhabitants being good agriculturists, brave in war, and living under an excellent system of Government run by the aristocracy with justice and moderation. Their elephant corps was stronger than that of other peoples (M’Crindle, The Invasion of India by Alexander the Great, p. 121).

One very important thing about the political condition of northern Panjab in the latter part of the fourth century is that old tribal oligarchies, like the Madras, Salvas, Balhikas, had disappeared, their names now surviving in the Khatri caste names of Madan, Saluja, Bahl and Wahi respectively, giving place to monarchical states of cohesive organisation. Under their pressure some of these oligarchies had migrated to southern Panjab and carved out their territories there.

The Shibis (Siboi) lived between the Indus and the Jhelum, their capital, Shivapura, lying just above the confluence of the Jhelum with the Chenab in the Jhang district. They had also spread upto Sind, where Sehwan indicates their settlement, and passed on to Baluchistan where the station of Sibi, between Sukkar and Quetta, reminds us of their habitation. This triangular tract of land with Sibi in Baluchistan, Sehwan in Sind and Shivipura in Jhang came to be occupied and populated by them. According to Curtius they dressed themselves with the skins of wild beasts and had clubs for their weapons (M’Crindle, Op. cit p, 232) which shows that they had not crossed the primitive tribal stage. They seem to have gone there from their habitat in eastern Panjab. Their modern descendants seem to be the Chibs.

To the south-east of the Sibis, in the region below the confluence of the Jhelum and the Chenab, were the Agalassians or the Agreyas. They were formidable warriors and could muster an army of 40,000 foot and 3,000 horse against Alexander. They had also gone there from East Panjab and Hariyana where their seat is still known as Agroha. Their modern descendants are the Agravalas.

To their south, from the southern

[p.75]: part of, the doab between the joint stream of the Jhelum and the Chenab and the Ravi to the region of the confluence of the Chenab and the Indus, were the Malavas. They were a considerable people with many citadels and strongholds like Kot-Kamalia, a small but ancient town on the bank of the Ravi, Tulamba on the other side of the Ravi on the high road to Multan, Multan itself at a distance of 54 miles from there via Atari, where a colony of Brahmana warriors lived, and many other cities round about. These Malavas appear to have been pushed downwards from the north and the east by other peoples.

Cognate to the Malavas were the Kshudrakas between the Ravi and the Sutlej in the region of Bahawalpur extending as far as the junction of the Sutlej with the Indus and the vicinity of Ucch. Among them only the members of the tribal oligarchy were called Malavya and Kshaudrakya, the slaves and free labourers being debarred from the use of these names, as we learn from Patanjali’s comments on Panini’s Sutra IV, 1, 168. As pointed out by me elsewhere, the Kshudrakamalavas were one people, a branch of the Madras. Being an off-shoot, they became known as Kshudrakamalavas (Small Malavas) in contradistinction to the main branch of the Madras-Mallas-Malavas. Later on they broke into two parts calling themselves Kshudrakas and Malavas respectively. In the sutras of Panini these Kshudrakas and Malavas are distinctly mentioned. Patanjali refers to wars singly fought by the Kshudrakas without the collaboration of the Malavas (ekākibhih Kṣudrakairjitam). Arrian states that they were very jealous of their freedom and Curtius writes that they were often at war with the Malavas (Buddha Prakash, Glimpses of Ancient Panjab, p. 37).

But the menace of Poros and then the invasion of Alexander drew them together leading them to cement their alliance by intermarriage, each people taking or giving in-exchange 10,000 of their young women for wives (M Crindle, Opcit., p. 287). This shows the process of coalition or amalgamation that was uniting the tribal oligarchies into larger groupings. In the midst of these people also live at Atari colony of Brahmana-warriors, living by the profession of arms, which reminds us of the fighting Vatadhana Brahmans, perhaps, modern Bhattis.

Along the Chenab, below its confluence with the Ravi, were the Abastanoi of Arrian or Sambastai of Diodoros who can be identified with the Ambashthas of the Mahabharata

[p.76]: (II, 52, 15), the Bhagavata (X, 83, 23), Brahmanda (III, 74, 22), Matsya (48, 21), Vayu (99, 22) and Visnu (II, 3, 18) Puranas and Panini’s Sutra (VIII, 30, 97). Curtius writes that they were a warlike people whose army consisted of 60,000 foot, 6,000 horse and 500 chariots. That they represented a confederacy of autonomous oligarchical units is manifest from the remark of Diodoros that “they dwelt in cities in which the democratic form of government prevailed” (M’Crindle, Op. cit. p. 292). The fact that they lived earlier in eastern Panjab and migrated from there to the south can be gathered from their association with the Sibis and the Yaudheyas in old tradition (Pargiter, Ancient Indian Historical Tradition, pp. 109, 264). They went further south and settled near the Mekala Hill at the source of the Narmada.

At the confluence of the Chenab and the Indus lived the Xathroi, the Kṣatragaṇa of the Mudraraksasa and the Kshatriyas and Rajanyas of Panini’s Sutras VI, 2, 34 and IV, 1, 168. They had specialized in riparine activity. It appears that they were also pushed down from the north.

In the same region were the Ossadioi or Vasatis whose descendants are probably the modern Sobtis. In Indian texts they are coupled with the Mauleyas who were spread upto the confluence of the Sutlej and the Indus and farther into Sind as well.

In Sind again, which had been under Achaemenian rule, there were monarchical states ruled over by kings like Mousikanos, Oxykanos, Sambos and Moeres.

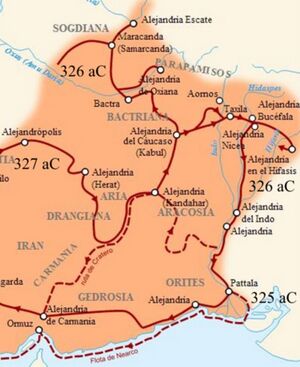

Alexander invaded Punjab in 327 B.C.

Thus it is clear that, in the latter half of the fourth century, the Panjab was broadly divided into two socio-political zones, the northern dominated by monarchical states and the southern consisting of tribal oligarchical communities which were pushed down by pressures from the former and driven to form larger federations with a tendency towards cohesion and merger. It was this Panjab which Alexander invaded in 327 B. C.

In the spring of 327 B. C. the Macedonian conqueror Alexander crossed the Hindukush and was on the road to the Indus.

At Nikaia, near modern Jalalabad, he divided his army into two parts, one under Hephaistion and Perdikkas was ordered to proceed through the Kabul Valley towards Gandhara and the other under him was to advance in the hilly country north of the Kabul river.

Ascending the valley of the Kunar, he reduced the clans of the highlanders. The people offered him stubborn resistance. In one of the encounters he was wounded in the

[p.77]: right shoulder and his officers, Ptolemy and Leonnatos, were also injured. The operation against the Aspasians (Ashvayana) was quite stiff. They set fire to their city, probably Gorys, and fled in the mountains and thence harassed the invader.

Another clan of them also burnt their town of Arigaion, modern Naoghi, and fled to the hills. To comb the area, Alexander divided his army into three parts, but the Indian mountaineers, who “were the stoutest warriors in the neighbourhood”, as Arrian remarked, fought for every hillock.

Alexander attacks Assakenoi

[p.77]: Then he advanced towards the Assakenoi (Ashvakayana) who had mustered 20,000 cavalry and more than 30,000 infantry, besides 30 elephants, at their capital Mashakavati, modern Maskhine or Massanagar, twenty-four miles from Bajaur. As he approached the walls, a group of 7,000 sallied out to pounce on him. Alexander retreated to a hillock to take position. The Ashvakayana force charged helter-skelter. Alexander suddenly wheeled round and charged back killing 200 and driving the rest into the citadel. Then he brought the phalanx against the fortifications. From the battlements a rain of arrows poured, one injuring Alexander’s ankle. Next day he pounded the wall with his engines and his soldiers tried to rush in through a breach, but the defenders repelled and rolled them back. On the morrow the Macedonians returned to the assault and shot from the engines as well as a wooden tower inside the citadel, but were unable to force their entry into it. On the following day a bridge was thrown from an engine to a section of the battered wall, but it collapsed under the weight of the men who were crossing over it. In that crisis the defenders also showered volleys of arrows and missiles. The invaders had to withdraw with losses. Next day another bridge was made to effect a passage into the fort. In the meantime the chief of the clan fell from a blow of a missile. His people also suffered a lot. Ultimately they decided to submit. According to the armistice they left the citadel and encamped on a hill thinking of fleeing to their homes at night. But Alexander fell on them and cut them to pieces and also stormed the empty citadel capturing the mother and daughter of the dead chief.

Alexander captured Bazira, Ora, Aornos,

[p.77]: Thereafter he captured Bazira and Ora, turned west and reduced the cities of West Gandhara. Local chiefs, like Kubhesha and Ashvajit, surrendered and Hastin of Pushkalavati also gave way.

Then Alexander returned to invest the fortress of Aornos (Varana) and took it after heavy fighting. Meanwhile Hastin also revolted and resisted from his citadel. Hephaistion laid siege to it and captured it in thirty

[p.78]: days. Hastin ultimately fell, perhaps, due to the defection of some kinsman or general named Sanjaya. The Macedonians took the opportunity of befriending him at the instance of the king of Takshashila and enthroned him in place of Hastin.

Macedonians massed on the Indus and Jhelum

[p.78]: The Macedonians were now massed on the Indus. A bridge was made over it at Und. Galleys and boats were ready. The king of Takshashila waited with rich presents. If it came to surrender, he preferred the foreigner Alexander to the native Poros. The Greeks poured and paraded in Takshashila. Envoys of the king of Abhisara and one Doxares, perhaps ruler of Darva, waited on him. Ultimatum was issued to Poros to the east of the Jhelum. But the Paurava chief was of different cast. He longed for the supreme moment of his life when he would smash the power of local princelings supported by the foreigners. Accordingly he took the gauntlet and prepared for the encounter.

Alexander and the king of Takshashila and other allies advanced on the Jhelum. He had 5,000 cavalry and infantry men of the Agema (Companions), 5,300 horsemen led by Koinos, 14,500 light horse-archers, 15,000 infantry, 86 elephants and numerous balists and catapults, and the king of Takshashila led 5,000 troops.

The army, which Poros mustered on the opposite side, is variously assessed, Plutarch giving its strength as 20,000 foot and 2,000 horse and Arrian raising the figures to 30,000 infantry, 4,000 cavalry, 300 chariots and 200 elephants, and Diodoros increasing the number of loot to 50,000 and chariots to 1,000, keeping in mind perhaps his total military establishment. Both sides remained in a state of suspense for quite a long period of time, one desirous of stealing a passage across the river and the other determined to oppose and pounce on it. The rush and push of soldiers, parading and endeavouring to swim over to the other side, must have invested the scene with bristling expectancy ; and the crowding and colliding of horses and elephants, neighing and trumpeting with restless fury, must have aroused the spirits of even the worst truants. For about a month the din and bustle and rattle and rumble continued to respond to the tempestuous torrents of the heavens and the roaring eddies of the Jhelum.

Alexander’s horse killed

[p.78]: At last, towards the end of June or the beginning of July, Alexander managed to move seventeen miles away from his camp and in a dark stormy night effected the crossing of the forbidding river. Just as he and his army were straightening themselves, a reconnaissance party, led by a son of Poros, struck at them. The conflict was sharp. Alexander’s horse was wounded and killed

[p.79]: and he fell head-long on the ground to be saved by his attendants. But the earth was so muddy that the Indian chariots stuck in it, some even plunging into the river, for there was little to distinguish it from the bank, and the soldiers could not set their long bows on the earth and press them by the foot properly with the result that their shots were desultory and ineffective. So mud and water assisted the Macedonians to crush and rout that party in the initial encounter. The son of Poros fell and his men were destroyed or dispersed, but this event created a stir all around and set Poros arraying his troops for the battle.

On the spur of the moment he sent his brother Aja (Hages) with 100 chariots and some cavalry to obstruct the enemy and himself arrayed his army in battle order posting the elephants in front of his line at intervals of 33-1/2 to 50 yards and drawing the infantry behind them incompact lines and placing the cavalry at the ends with the chariots in front of them.

Alexander ordered the Scythians and the Dahae to attack Aja : (Hages) and then launched Perdikkas to hit his right wing and deployed his cavalry, formed into two units under himself and Koinos respectively, to the right and placed the hypaspists after it and the phalanx and light troopers on either flank. While the fight of Aja (Hages) and Perdikkas raged with breathtaking vigour, Poros indulged in the formality of asking the Macedonians to surrender their king, but, without heeding it, Alexander ordered the charge and an advance squadron of one thousand mounted archers made a piercing attack on his left wing and he himself rapidly marched forward and fell upon it. This cavalry charge broke the phariots down whose unwieldiness-each chariot was 7.5 feet high and 9 feet wide drawn by four horses and carrying six men, two drivers, two shield-bearers and two archers-added to the immobility on account of plashy ground.

Alexander attacks Poros

[p.79]: Seeing this the cavalry of Poros assembled from both the sides to repel the onslaught. But Koinos swung to the right and attacked it on the rear. Caught between the two attacks, it hastily broke into two sections to face the assaults from the two sides. But as the horsemen were changing positions, Alexander and Koinos drove home the charge from the front and the rear throwing them into utter disorder and forcing them to fly along their own front to take refuge in the spaces between the elephants.

In that critical moment Poros ordered the elephants to dash forward. Each elephant carried there archers, besides the mahout, and bore a vast load of darts and missiles to be hurled at the

[p.80]: enemy. Poros, himself an exceptionally tall figure, was mounted in the covered howdah of a gigantic elephant, striking terror by his supernatural stature and majesty as well as the bolting blows of his torrents of darts. Under his command the elephants trumpeted and trampled and the warriors on them rained arrows and javelins. The infantry also closely followed dealing vigorous blows and the cavalry wheeled round from the rear charging the opposite lines. This charge was frightening and smashing. As Curtius writes the elephants terrified not only the horses but also the men and disordered the ranks so that those, who just before were victorious, began to look round them for a place of safety and flight. The most dismal of all sights was when the elephants would by their trunks grasp the men, arms and all, and, hoisting them above their heads, deliver them over into the hands of their drivers or dash them on the ground. Most of them they crushed and gashed and gored to pieces with their tusks. The terror and carnage must have been heavy.

To ward off the attack the macedonians began to hack the feet of the elephants with axes and hurl chopper-like curved swords at their trunks irritating them so much as to make them out of the control of even their drivers. As a result they trampled helter skelter sparing neither friend nor foe and throwing their own ranks in confusion. But Poros maintained his balance and poise and, rallying round him forty elephants that were in discipline, personally mounted a murderous charge on the Macedonians. Diodoros states that he spread great terror and slaughter with his own hand flinging a shower of javelins like shots of a catapult. His elephant also displayed remarkable sagacity defending him against his assailants and extracting the darts from his body with his trunk and side by side butting against them and pushing them back. Fighting so prominently, Poros became the target of all marksmen and received nine wounds including one on the right shoulder where he had no armour. Yet he went on darting his bolts with cool and heroic courage till he felt exhausted and his mahout turned his elephant gently back. Alexander rode to pounce on him, but his horse writhed with blows and sank under him lowering him on the ground. Meanwhile the battle raged with grim intensity. Arrian writes that the Macedonian cavalry had gathered into one battalion, being thrown together in course of the struggle, and attacked the elephants and horsemen of Poros in massive charges. Operating from a wide and open field, they inflicted a severe loss on the army

[p.81]: of Poros that was cooped up within a narrow space. Frequently they advanced and, when the elephants charged, retreated and again dashed forward striking and irritating the beasts. In this course of advancing and retreating and striking and shooting, the elephants lost their feet and merely trumpeted and stampeded backward with their faces towards the Macedonians. In that moment of exhaustion Alexander surrounded the whole enemy line with his cavalry and signaled the infantry to link their shields and compactly move in phalanx. Meanwhile the Macedonian contingents crossed over from the other side of the river and reinforced the embattled army. Hence the cavalry of Poros was decimated and his infantry was exasperated, but the losses of the Greeks were no less severe.

Both sides suffered heavy losses

[p.81]: As the Ethiopic texts state, many of Alexander’s horses were slain and, by reason of this, there was such great sorrow among them that they wept and howled like dogs and wished to throw down their arms and forsake Alexander and go over to the enemy. When Alexander saw this, he drew nigh into their midst and wished to stop the fight.

Joseph Ben Gorion in his History of the Jews recaptures the scene as follows :

- “Now the war between the Macedonians and the Indians was prolonged until a great number of Alexander’s soldiers were destroyed and those (that remained) took counsel together to lay hold of Alexander and deliver him over to the King of India”.

Obviously both sides suffered heavy losses. But how the curtain dropped on the scene is obscured by the inconsistent, often contradictory, statements of historians. Arrian says that, when the mahout of Poros wheeled his elephant round, Alexander sent to him first the king of Takshashila , and, on his being rebuffed, messenger after messenger, and lastly his friend Heroes who persuaded him to meet the Macedonian King. In consideration of his friendship for Meroes and softened by his persuasive advocacy, Poros approached Alexander, unbroken and unabased in spirit, and met him on a footing of equality “as a brave man” would meet another brave man and, on being accosted by him, did not cringe like a vassal or crawl like a prisoner or grovel in the dust like a defeated person, but insisted on being treated as a king showing his jealous regard for his sovereignty and royal status. Alexander not only let him govern his kingdom, but “added another territory of still greater extent to it” which clearly suggests that he ceded it to him.

[p.82]: Curtius gives an altogether different version of the end of this battle. He says that, when Poros retired from the battlefield, Alexander himself pursued him and, when he could not advance due to the fainting of his horse, sent the brother of the king of Taxila whom he killed by a javelin. Thereupon the Greeks intensified their onslaught and wrought great slaughter. Poros also fell and then he was placed on a wagon. When he gained his senses, Alexander reprimanded him for his madness, whereupon he acknowledged the superior valour of him, but admonished him to be moderate in his demeanour. Alexander ordered his wounds to be attended to and presented him with a larger kingdom than that which he had.

Diodoros gives a third entirely different version. He reports that, when Poros fainted on his elephant, the rumour of his death spread resulting in the flight of the remnants of his army. A large number of men were slain and 9,000 were captured including, perhaps, Poros who was still alive. But he was given to the Indians for treatment by order of Alexander and later reinstated in his kingdom.

Plutarch has a fourth tale to tell by jumbling fragments from Diodoros and Arrian. Like Diodoros, he says that Poros was taken prisoner and, like Arrian, he adds that he insisted on being treated as a king. How a prisoner can claim to be treated as a king does not bother him.

Justin invents a fifth story. He states that, when Poros was imprisoned, he offered a hunger-strike and did not take any food or medicine which produced such an impression on the mind of Alexander that he restored him to his sovereignty. Where arms could not succeed hunger-strike delivered the goods !

Thus the five western historians are not consistent on any fundamental aspect of the end of the battle and contradict each other on many vital points.

The peace treaty of Poros and Alexander

[p.82]: All that emerges from them, even if we ignore Oriental and Ethiopic traditions, is that, as the eighth hour of the battle was in progress and, to quote Plutarch, "the battle depressed the spirits of the Macedonians”, Alexander clamoured for peace and, for that purpose, sent numerous envoys and messengers to Poros. Poros was adamant on shunning contact with his adversary and reluctant to meet him for any talk inspite of the severe losses he had sustained. Ultimately, through the persuasion one of his friends, Meroes, he consented to meet

[p.83]: Alexander and make peace with him. But, while doing so, he maintained his dignity as a king and asserted it in his conversation. Alexander also acknowledged his royal status, respected his sovereignty and added more territory to his kingdom. All this clearly shows that the battle ended in a treaty of peace between Poros and Alexander the essence of which was the preservation of the royal dignity of Poros, the cession of the territory conquered by Alexander to him and the joint endeavour of the two in reducing the independent tribes of the Panjab and also to advance on Magadha, if possible. This peace was made, when fighting was still continuing, despite severe losses on both the sides.

The motive behind the peace must have been the decision of Poros to make Alexander an instrument of reducing the recalcitrant tribes and states of the Panjab and create out of them a unified empire. Accordingly further Macedonian advance beyond the Jhelum was the joint venture of Poros and Alexander.

Soon after the treaty of Alexander and Poros the latter’s nephew, reigning between the Chenab and the Ravi, fled to the east to Magadha, since he had tried to become independent of his uncle, when the menace of the invasion hanged over him, and was mortally afraid of the redoubled might of him after the battle of the Jhelum. The king of Abhisara, who was playing a double game from the outset, now ended his hesitation and joined the allies. The Glaucukayanas also easily gave way. Thus many problems of political consolidation in western Punjab were instantly solved.

War with Kathaians

[p.83]: Then Alexander and Poros crossed the Ravi. There the Kathaians (Kashas) resisted them. The village of Kathania near Jundiala in Amritsar district represents their settlement. They enjoyed the highest reputation for courage and skill in the art of war and shared the warlike spirit of the Kshudrakas and the Malavas, as Arrian states. Among them the practice of widow-burning prevailed. First Alexander marched against the Adrestai (Arattas), reduced some of their cities, which offered resistance, and persuaded others to surrender. Then he moved against the stronghold of the Kathaians, called Sangala, where they, along with a group of other neighbouring tribes, had gathered to resist him, and encamped at the site of the villages, Kholali and Chokawana, ten miles to the west of Amritsar, as traditions current in that area show. On a low hill before the citadel the Kathaians formed their battle-array encircling it with a triple row of wagons, a sort of Sakaṭavyūha. That strategy alarmed the Macedonians and they had to make

[p.84]: careful arrangements to meet it. On their right wing were placed the horseguards and the cavalry regiment of Kleitos, then the hypaspists, then the Agrianians and then the cavalry and infantry under the command of Perdikkas. On both the wings the bodies of archers were posted. The infantry and cavalry, that arrived from other places in the rear, was also divided in two parts and sent to the two wings. When the disposition was complete, Alexander ordered the cavalry on the right wing to advance against the left side of the wagons. But the Kathaians, instead of sallying out from behind the wagons to attack the advancing cavalry, mounted upon them and began to shoot from their tops. Leaping nimbly from wagon to wagon, they plied the enemy with pikes and axes also. Thus fighting, they foiled and repulsed the Greek cavalry with considerable losses. Seeing the cavalry fail, Alexander dismounted and led the infantry on foot. The compact lines of the phalanx, charging with their twenty-four feet long spears, drove the Kathaians from the hist row of the wagons. But, in front of the second row they formed a strong and compact line and vigorously attacked the assailants. Quietly drawing back the wagons of the first row, they sallied through the gaps at the enemy. The Greeks were pushed back again. But they recovered and made a dashing charge, driving the Kathaians from the second to the third row and then pushing them back into the citadel. The circumference of the citadel was so big that the Macedonian army could not surround it in its entirely. However Alexander posted the whole of the cavalry by the side of a lake near a gap in his siege through which a flight from the citadel could be effected. At night the Kathaians began to drop from the wall on that spot but were killed by the cavalry. Finding the passage impossible, they hustled back into the citadel leaving many dead. Thereupon Alexander was even more cautious and posted Ptolemy at that place. About the fourth watch of the night the men inside opened the gate facing the lake and rushed out in full speed. But Ptolemy fell upon them goading them again inside the citadel. Five hundred of them perished in the retreat. Next day was a crucial one, but Poros suddenly came with his elephants and a force of 5,000 Indians and gave a new turn to the operation. The Macedonians under-mined the walls and, planting ladders round it, quickly jumped inside and spread slaughter. According to Arrian 17,000 Kathaians were killed and 70,000 captured. Two other cities were up in arms, but the fall of Sangala cowed them down and

[p.85]: Alexander extended to them lenient treatment in case they stopped resistance. However he was not true to his word and attacked them during the flight killing about 500. Then he razed the city of Sangala to the ground and, sending Poros to introducer garrisons in the cities that had submitted, himself advanced east wards. In course of this march he fell on another city where the neighbouring people had taken refuge. But a dissension arose among those people, some preferring to fight to the finish and others deciding on surrender. During the discussion some opened the gates and admitted the Macedonians. But, says Curtius, Alexander was so lenient as to pardon the defenders and take hostages from them whom he utilized to bring other towns to submission. Thus one town fell after another till he reached the Beas, The Greeks of Sophytes and a king, Bhagala, offered their submission, but the reports about the military strength of the people, living to the east of the Beas, were so alarming that the Macedonians refused to move despite the entreaties of Alexander and the assurance of many others like Poros. Baffled and stifled by the mutiny, Alexander had to retreat and, reaching the Jhelum, appointed Poros king of all the Indian territories already subjugated, seven nations in all, containing more than 2,000 cities, towns and villages.

Alexander decided to go back

[p.85]: From the capital of Poros Alexander decided to go back through South Panjab and Sind either because the route through the North-West was barred by rebellious mountaineers or because Poros thought it prudent to advise him to invade the tribal oligarchies of the south with a view to weakening them. Already a resistance movement seems to have been gaining momentum there. Hence Alexander rapidly passed through the turbulent confluence of the Jhelum and the Chenab and made a sudden inroad into the territory of the Sibi and other people to prevent them from-joining the Malavas. Then marching to the bank of the river Ayek, somewhere between Jhang and Shorkot, he ordered his army a short repose so that they could fill whatever vessel they had with water. After ensuring water supply he plunged into the desert tract, called Sandarbar, and, covering it in one day and night, reached the Malava stronghold of Kot Kamalia. The people could not expect Alexander’s march through that perilous route and were working in their fields unarmed. Alexander fell upon them killing some and driving the rest inside the city which, he eventually took by storm. From there he advanced on

[p.86]: and in the way intercepted the fugitives when they were crossing the Ravi. The brigade of Peithon stormed that city whereas Alexander himself invested the citadel of the Brahmanas at Atari where many Malavas had taken refuge. Finding their position-difficult, the defenders of this citadel left the walls and retired inside. A few Macedonians also rushed in, but were thwarted and pushed out. On this the besiegers scaled the walls by ladders and undermined a tower and crowded in through the gap. The defenders fought bravely and, finding resistance difficult, set fire to their houses and plunged in the vortex of slaughter. About 5,000 were killed but only a few were taken prisoners.

From Atari, Alexander moved towards the Malava capital, Multan, only next day. The Malavas, now keenly conscious of the danger, organized a defence in association with the Kshudrakas. The report of their preparation sent a shudder through the Macedonians. Some said they were 50,000, others assessed their strength at 80,000 foot, 10,000 cavalry and 700 chariots and many estimated their figures at 90,000 foot, 10,000 horse and 900 chariots. They began to quail and grumble and upbraid Alexander for taking the course of retreat through such ferocious and numerous warriors. However the instability of tribal oligarchies came to their rescue. A difference arose among the Malavas and Kshudrakas on the score of leadership. In the evening a Kshudraka warrior was chosen as the head of the confederate army. This experienced general had encamped qt the foot of a hill and ordered fires to be lighted over a wide circuit to make his army appear so much the more numerous. But, in the night, they quarrelled and reproached and annoyed each other and by-daybreak were a rabble of discordant elements straggling to and fro with no unity of strategy or purpose. Most of them seceded from the array and drew off into their adjoining towns. The whole line melted into thin air leaving the field free for Alexander.

Malava marksman arrow injured Alexander

Next day the Macedonians laid siege to Multan and burst into the city through a small gate. But the scaling of the-citadel inside was a tough job and the soldiers, carrying the ladders, were loitering too much. To end that vacillation Alexander himself snatched a ladder from a man and, setting it against the wall, quickly ascended the parapet. His shield-bearer Peukestas and bodyguard Leonnatos also followed him. Seeing their chief alone on the parapet, the hypaspists also rushed on up the ladder in undue haste. But the ladder broke

[p.87]: down under the extraordinary weight of so many men and they tumbled down in a mass barring the way for others also. At that moment shots from all directions were hitting Alexander, but not losing heart, he leaped down into the citadel and, taking the support of the wall and the trunk of a tree, showed remarkable valour in defending himself. The governor of the place, perhaps, the chief of that unit of the tribe, assailed him alone but fell at his hands. But the crowd plied him with darts and flings from all sides. Just then Abreas and Peukestas and, following them, Leonnatos jumped into the citadel and were with Alexander. But a rain of arrows pierced the forehead of Abreas and bored the buckler of Alexander and a shower of stones shattered his helmet and a blow of club fell on his neck. Unable to hold his own he sank on his knees and kept protecting himself in a crouching position. Just then a Malava marksman shot an arrow, two cubits long with an iron barb three fingers’ breadths in width and four in length, which pierced through Alexander’s cuirass into his ribs above the pap. A gush of blood with gurgling air sallied from his chest and he collapsed in a swoon. A deafening cry of his fall rang on all sides. The Macedonians were mad with rage and desperately plunged into the citadel, some swinging along pegs driven in the wall, others mounting upon one another and many through a breach in a gate. A savage fight ensued in the citadel in which nobody cared for men, women or children. At last Alexander was carried to his camp where his surgeon Critobulus and the general Perdikkas performed, the operation and extracted the barb from his chest. For sometime he hovered between life and death, but in the end survived the shock and, after a week or so, was again up on his feet. This miraculous survival confirmed the belief of the people in the divine ancestry of Alexander and the remaining Malavas and, after them, the Kshudrakas offered their submission. Soon the Kshatriyas and the Vasatis also gave way and the region up to the confluence of the Chenab and the Indus was at the feet of the Macedonians.

The Malavas and their kinsmen, the Kshudrakas, were brave, warlike, freedom-loving and of uncommon height and dignified bearing. Riding glittering chariots and wearing robes of linen, embroidered with inwrought gold and purple, they looked like personifications of gallantry and heroism. But they

[p.88]: were isolationist, self-contained and narrow-minded and lacked in the spirit of unity and cooperation with their colleagues. Thus it was easy for an effective force with good intelligence service and sound coordination system to make short shrift of them. After Alexander Poros stepped into his shoes as the conqueror of these peoples as well as those of Sind, as the fact that he ousted the Macedonian satrap Peithon from Sind indicates.

The above account of the heroic resistance, offered by the people of the Panjab to the invasion of the Macedonians, led by Alexander, brings into bold relief the salient features of the socio-political transformation through which the region was passing. Northern Panjab had switched over to centralized monarchical rule and southern Panjab was clinging to the tribal oligarchical system. Whereas the former had gathered enough strength to resist a foreign invader, the latter was rent by dissensions and bickerings which made effective resistance impossible.

Alexander’s three years of campaigning from May 327 B.C., when he crossed the Hindukush, to May 324 B.C. when he reached Susa, particularly the period of nineteen months, from March 326 B.C., when he crossed the Indus at Ohind, until September or October 325 B.C., when he entered the territory of the Arabioi, that he spent in the Panjab, gave the struggle between these two systems the final and finishing touches. In this work he proved to be an instrument of the policy of Poros.