Heruli

| Author:Laxman Burdak, IFS (R) |

Heruli () were an early Germanic people. Possibly originating in Scandinavia, the Heruli are first mentioned by Roman authors as one of several "Scythian Jats" groups raiding Roman provinces in the Balkans and the Aegean Sea, attacking by land, and notably also by sea. During this time they reportedly lived near the Sea of Azov.

Variants

- Herules

- Heruls

- Herulians/Herulian

- Eruli

- Erules

- Erouloi (Ερουλοι)

- East Herules

- Ostherules

Name

The name of the Heruli is sometimes spelled as Heruls, Herules, Herulians or Eruli.[1] In the earliest mentions of them in 4th century records, they are called Eluri instead, leading to some doubts about whether they were the same people.[2]

The name Heruli was often written without "h" in Greek (Έρουλοι, 'Erouloi') and Latin (Eruli), and is sometimes thought to be Germanic and related to the English word earl (see erilaz) implying that it was an honorific military title. [3]There is even speculation that the Heruli were not a normal tribal group but a brotherhood of mobile warriors, though there is no consensus for this old proposal, which is based only on the name etymology and the reputation of Heruli as soldiers.[4]

Origin

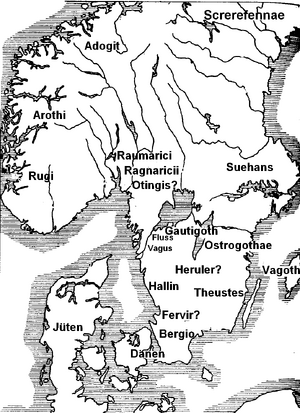

Origins: The origins of the Heruli are traditionally sought in north-central Europe. Heruli were Germanic-speaking group originally from north central Europe, some of whom migrated to regions north of the Black Sea in company with Goths and others in the 3rd century.[5]possibly Scandinavia.[6][7][8]

Jat clans

Jat Histpry

Harral (हर्रल) : Bhim Singh Dahiya[10] has provided Clan Identification Chart where Jat clan Harral = Heruli. Harral (हर्रल) is a Jat clan found in Shahpur, Pakistan.[11]

Haral (हराल)[12] [13] is a Muslim Jat clanfound in Pakistan. It is the sub gotra of the Khokhar Jats. [14] It is a subdivision of Khokhar Gotra. [15]

History

From the late 4th century AD the Heruli were one of the peoples that were brought into the fold of the Hunnic Confederation of Attila. By 454, after the death of Attila, they established their own kingdom on the Middle Danube, and Heruli also participated in successive conquests of Italy by Odoacer, Theoderic the Great, Narses and probably also the Longobards. However, their independent kingdom was destroyed by the Longobards by the early 6th century AD. A part of this population subsequently became established inside the Roman empire near Belgrade, and continued contributing fighting men to the Eastern Roman empire, and participating in Balkan and Italian conflicts.

With their last kingdom eventually dominated by Rome, and smaller groups integrated into larger political entities, the Heruli disappeared from history around the time of the conquest of Italy by the Lombards.

In his 6th century work Getica, the historian Jordanes, based in Constantinople, wrote that the Heruli had been driven out of their homeland in Scandinavia by the Danes.[16] This has been read as implying Heruli origins in the Danish isles or southernmost Sweden. On the other hand, his contemporary Procopius recounted a migration of a sixth-century group of Heruli noblemen to Thule (which for him, but not Jordanes, was the same as Scandinavia), from their "homeland" on the Middle Danube. [17] Later, Danubian Heruli found new royalty among these northern Heruli.[18] This account has been seen as implying an old and continuous connection between the Heruli and Scandinavia, although some recent scholars are skeptical of this interpretation, and have noted that Procopius does not depict the Heruli as returning to a homeland, but as leaving their homeland.[19][20]

Ellegård has proposed that the Danish expulsion of the Heruli might have happened in the 6th century, and been an expulsion of the immigrants from the Danube: "the only thing we can say with reasonable certainty is that a small group of Eruli lived there for some 38-40 years in the first half of the 6th century A.D.". He proposes that the evidence makes it most likely that "a loose group of Germanic warriors which came into being in the late 3rd century in the region north of the Danube limes that extends roughly from Passau to Vienna". [21]

On the Pontic-Caspian steppe

The Heruli are believed to have migrated towards the region north of the Black Sea in the 3rd century AD. Other Germanic peoples, such as the Rugii and the Goths, are believed to have carried out a similar migration at this time. These peoples replaced the Sarmatians as the dominant power north of the Black Sea. The Sarmatians had in the 1st century AD replaced the Bastarnae, who are believed to have been a Germanic people. The arrival of the Heruli has been seen as part of a bigger cultural shift in this region, involving the migration from the northwest of Germanic peoples, who replaced the Sarmatians as the dominant power in the region.[22]

The first relatively clear mention of the Heruli by Graeco-Roman writers concerns two major campaigns into the Balkans of 267/268 and 269/270.[23] Goths, Heruli (referred to as "Eluri", Ἔλουροι, in the oldest sources), and other "Scythian" peoples from the region of the Sea of Azov, took control of Black Sea Greek cities, and gained a fleet that they used to launch raids along the northern Black Sea and as far as Greece and Asia Minor. These invasions began in the reign of Gallienus (260-268 AD), and continued until at least 269 during the reign of Marcus Aurelius Claudius, who subsequently took up the title "Gothicus" due to his victory.[24][25]

In 267, Heruli (Αἴρουλοι) commanded a naval attack from the Sea of Azov, past the Danube delta, and into the straits of the Bosphorus (the area of modern Istanbul). They took control of Byzantion and Chrysopolis before retreating to the Black Sea. Emerging to raid Cyzicus, they subsequently entered the Aegean Sea, where they troubled Lemnos, Skyros and Imbros, before landing in the Peloponnese. There they plundered not only Sparta, the closest city to their landing site, but also Corinth, Argos, and the sanctuary of Zeus at Olympia. Still within 267 they reached Athens, where local militias had to defend the city. It seems to have been the Heruli specifically who sacked Athens despite the construction of a new wall, during Valerian’s reign only a generation earlier. This was the occasion for a famous defense made by Dexippus, whose writings were a source for later historians.[26]

Further north, in 268, Gallienus defeated Heruli at the river Nestos using a new mobile cavalry, but as part of the surrender a Herulian chief named Naulobatus became the first barbarian known from written records to receive imperial insignia from the Romans, gaining the rank of a Roman consul. It is highly likely that these defeated Heruli were then made part of the Roman military.[27][28]

Recent researchers such as Steinacher now have increased confidence that there was a distinct second campaign which began in 269, and ended in 270.[29] Later Roman writers reported that thousands of ships left from the mouth of the Dnieper, manned by a large force of various different Scythian peoples, including Peuci, Greutungi, Austrogothi, Tervingi, Vesi, Gepids, Celts, and Heruli. These forces divided into two parts in the Hellespont. One force attacked Thessaloniki, and against this group the Romans, led by Claudius now, had a major victory at the Battle of Naissus (Niš, Serbia) in 269. This was apparently a distinct battle from that at the Nessos. A Herulian chieftain named Andonnoballus is said to have switched to the Roman side, and this was once again a case where Heruli appear to have joined the Roman military. The second group sailed south and raided Rhodes, Crete, and Cyprus and many Goths and Heruli managed to return safely to harbor in the Crimea. Lesser attacks continued until 276.[30]

The Heruli are believed to have formed part of the Chernyakhov culture,[31] which, although dominated by the Goths and other Germanic peoples,[32] also included Bastarnae, Dacians and Carpi.[33] The Heruli are thus archaeologically indistinguishable from the Goths.[34][35]

Jordanes reports that the Heruli in the late 4th century AD were conquered by Ermanaric, king of the Greuthungian Goths.[36] Ermanaric's realm may also have included Finns, Slavs, Alans and Sarmatians.[37] Before being conquered by Ermanaric, Jordanes says that the Heruli were led by their king Alaric.[38]Herwig Wolfram has suggested that the future Visigothic king Alaric I may have been named after this Herulian king.[39]

Doubts have been raised about this earliest, Black Sea period in the history of the Heruli. The first author known to have equated these "Eruli" with the later "Eruli" was Jordanes, in the 6th century.[40]

The "western" Heruli, soldiers and pirates

The proposal that there may have been a Western kingdom of Heruli has posed a problem for scholars. This question arises because of the evidence of Heruli activity in the western Roman empire. The existence of this western kingdom is increasingly doubted.[41]

Heruli were already seen in western Europe before the empire of Attila, at the time of their first ambitious campaigns in the east. In 268 Claudius Mamertinus reported the victory of Maximian over a group of Heruli and Chaibones (known only from this one report) attacking Gaul.

It is believed that it was from this time that the Romans instituted a Herulian auxiliary unit, the Heruli seniores, who were stationed in northern Italy. This numerus Erulorum was a lightly-equipped unit often associated with the Batavian Batavi seniores. In 366 the Batavians and Heruli fought against the Alamanni near the Rhine, under the leadership of Charietto, who died in the battle, and then against Picts and Scoti in Britain. They were subsequently sent to fight Parthians in the east.[42]

In 405 or 406, a large number of barbarian groups crossed the Rhine, entering the Roman empire, and the Heruli appear in the list of peoples given by the historian Jerome. However, this list is sometimes thought to have drawn on historical lists for literary effect.

Later mentions of Heruli in western incidents where they were not clearly connected to the Roman military include two sea raids in northern Spain in the 450s, and the presence of Heruli at the Visigothic court of Euric in about 475.[43]The raids were reported by Hydatius. Sidonius Apollinaris mentions Heruli at the Visigothic court in 476, although this is in a poetic letter. Recent scholars such as Steinacher and Halsall have pointed out that this type of evidence is consistent with the internal military conflicts that were happening in the Roman empire during this period. Halsall, for example, writes that it "must at least be a possibility that their raid constituted part of a Romano-Visigothic offensive against the Sueves", who had been part of an invasion of the same area. [44] Steinacher demonstrates using examples from the period, including Charietto's life story, that barbarian soldiers could switch from being Roman soldier, to pirate, and back to soldier.[45]

The Greek poet Sidonius Apollinaris specifically imagined the Heruli he saw at Euric's court as oceanic sea-farers, but Steinacher argues that this raiding by sea was simply a logical strategy for Visigothic campaigns against the Iberian Suevi, and difficult to use as a proof that the Heruli had a coastal kingdom somewhere in the north.[46]

- In reality, there is nothing special about attacks from the sea: various marauders employed such tactics at various points in history. It is just easier and not too dangerous.[47]

Given the writing style of Sidonius, this reference could also be "nothing more than a bookish reference to 3rd-century accounts of Herules attacking from the sea".[48]

Kingdom on the Middle Danube

In the early 5th century AD, large groups of peoples left the Middle Danube region, including the groups who crossed the Rhine in 405, many of whom eventually reached Iberia. Others crossed the Danube, like the forces of Radagaisus, who invaded Italy. During this period, the Huns and their allies begin to be found in this same area instead, having crossed the Carpathians from the east.[49] By 450 AD, the Heruli were firmly part of the Hunnic empire of Attila. The Gepids, Rugi, Sciri and many Goths, Alans and Sarmatians were also part of Attila's empire.[50]They were among the peoples who are reported as having fought for Attila at the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains.

After the death of Attila, his sons lost power over the various peoples of his empire at the Battle of Nedao in 454. The centre of this alliance was now settled upon the Roman border north of the Middle Danube. Heruli who were possibly on the winning side with the Gepids, were subsequently among the several peoples now able to form a kingdom in that area. The Herulian kingdom, was established north of modern Vienna and Bratislava, near the Morava river, and possibly extending as far east as the Little Carpathians. They ruled over a mixed population including Suevi, Huns and Alans.[51] Compared to other Middle Danubian kingdoms in this period, Peter Heather has described this Heruli kingdom as "middle-sized", similar to the Rugian one, but "clearly not as militarily powerful, say, as the Gothic, Lombard, or Gepid confederations which generated much longer-lived political entities, and into which elements of the Rugi and Heruli were eventually absorbed".[52]

From this region the life story of Severinus of Noricum reports that the Heruli attacked Ioviaco near Passau in 480.[53] The Heruli do not appear in early lists of Odoacer's allies after Nedao, but benefited from the downfall of his people the Sciri. They established control on the Roman (south) side of the Danube, north of Lake Balaton in modern Hungary when they were apparently able to take over the kingdoms of the Suevi and Sciri, who had been under pressure from the Ostrogoths, who continued to press their old allies from the south.[54]

Odoacer, the commander of the Imperial foederati troops who deposed the last Western Roman Emperor Romulus Augustus in 476 AD came to be seen as king over several of the Danubian peoples including the Heruli, and the Heruli were strongly associated with his Italian kingdom. The Heruli on the Danube also took control of the Rugian territories, who had become competitors to Odoacer and been defeated by him in 488. However Heruli suffered badly in Italy, as loyalists of Odoacer, when he was defeated by the Ostrogoth Theoderic.

By 500 the Herulian kingdom on the Danube, apparently by now under a king named Rodulph, had made peace with Theoderic and become his allies.[55] Paul the Deacon also mentions Heruli living in Italy under Ostrogothic rule.[56] Peter Heather estimates that the Herulian kingdom could muster an army of 5,000-10,000 men.[57]

Theoderic's efforts to build a system of alliances in Western Europe were made difficult both by counter diplomacy, for example between Merovingian Franks and the Byzantine empire, and also the arrival of a new Germanic people into the Danubian region, the Lombards who were initially under Herule hegemony. The Herulian king Rodulph lost his kingdom to the Lombards at some point between 494 and 508. [58]

Later history

After the Middle Danubian Herulian kingdom was destroyed by the Lombards in or before 508, Herulian fortunes waned. According to Procopius, in 512 a group including royalty went north and settled in Thule, which for Procopius meant Scandinavia.[59] Procopius noted that these Heruli first traversed the lands of the Slavs, then empty lands, and then the lands of the Danes, until finally settling down nearby the Geats.[60][61] Peter Heather considers this account to be "entirely plausible" although he notes that others have labelled it a "fairy story", and given that it only appears in one source it is possible to deny its validity.[62]

Another Heruli group were assigned civil and military offices by Theoderic the Great in Pavia in north Italy.[63]

What happened to the main part of the Danubian Heruli has been difficult to reconstruct from Procopius, but according to Steinacher they first moved downstream on the Danube to an area where the Rugii had sought refuge in 488. Here they suffered famine. They sought refuge among the Gepids, but wanting to avoid being mistreated by them crossed the Danube came under East Roman authority.[64][65]

Anastasius Caesar allowed them to resettle depopulated "lands and cities" in the empire in 512. Modern scholars debate whether they were moved then to Singidunum (modern Belgrade), or first to Bassianae, and to Singidunum some decades later, by Justinian.[66] This area had been re-acquired by the empire from the Goths, who now ruled Italy from Ravenna.[67]Justinian integrated them into the empire as a buffer between the Romans and the more independent Lombards and Gepids to the north. Under his encouragement, the Herule king Grepes converted to Orthodox Christianity in 528 together with some nobles and twelve relatives.[68] Procopius who felt that this made them somewhat gentler, also showed in his account of the wars against the African Vandals, that some of them were Arian Christians.[69]

The Heruli were often mentioned during the times of Justinian, who used them in his extensive military campaigns in many countries including Italy, Syria, and North Africa. Pharas was a notable Herulian commander during this period. Several thousand Heruli served in the personal guard of Belisarius throughout the campaigns, and Narses also recruited from them. They were a participant in the Byzantine-Sasanian wars, such as the Battle of Anglon.

Grepes and most of his family had apparently died by the early 540s, possibly in the Plague of Justinian (541-542).[70] Procopius related that in the 540s the Heruli who had been settled in the Roman Balkans killed their own king Ochus and, not wanting the one assigned by the emperor, Suartuas, they made contact with the Heruli who had gone to Thule decades earlier, seeking a new king. Their first choice fell sick and died when they had come to the country of the Dani, and a second choice was made. The new king Datius arrived with his brother Aordus and 200 young men.[71] The Heruli who were sent against Suartuas defected with him and were supported by the empire. The supporters of Datius, two thirds of the Heruli, submitted to the Gepids.[72] This period of rebellion against Rome lasted approximately 545–548, the period immediately before conflict between their larger neighbours the Gepids and Lombards broke out, but this rebellion was repressed by Justinian.[73]

In 549, when the Gepids fought the Romans, and Heruli fought on both sides.[80] In any case after one generation in the Belgrade area, the Herulian federate polity in the Balkans disappears from the surviving historical records, apparently replaced by the incoming Avars.[74]

Peter Heather has written that:

- by c.540 being a Herule had ceased to be the main determinant of individual behaviour; the Heruli had ceased to operate together on the basis of that shared heritage, and different Heruli were adopting different strategies for survival in the new political conditions which even caused them to fight on opposing sides. After c.540, we still find small groups called Heruli fighting for the East Romans in Italy, and it is noticeable that the Roman commanders were careful to appoint for them leaders of their own race. Thus some sense of identity probably remained. That said, we are clearly dealing with a few fragments of the original group, and, in the prevailing circumstances, Herule identity had no future.[75]

Sarantis however shows that the Belgrade-region Heruli continued to be recruited, and to play a role in local conflicts involving the Gepids and Lombards, into the 550s. Suartas, a Herule general for the Romans, led Herule forces against the Gepids in 552 for example.[76] However it appears that by this period the semi-independent Heruli near Belgrade became Roman provincials.[77]

In 566, Sinduald, a Herule military leader under Narses, was declared a king of Heruli in Trentino in northern Italy, but he was executed by Narses. Sinduald was said to be a descendant of the Herules who had already entered Italy under Odoacer.[78]

Paul the Deacon writes that many Heruli joined the Lombard king Alboin in their eventual conquest of Italy from the empire in the late 6th century AD.[79]

Along with the Rugii and Sciri, the Heruli may have contributed to the formation of the Bavarii.[80]

External links

References

- ↑ Waldman, Carl; Mason, Catherine (2006). Encyclopedia of European Peoples. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 1438129181. p. 388.

- ↑ Steinacher, Roland (2010). "The Herules: Fragments of a History". In Curta, Florin (ed.). Neglected Barbarians. ISD. ISBN 9782503531250. p. 322.

- ↑ Neumann, Günter (1999). "Heruler: § 1. Philologisches". Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde. Vol. 14. Walter de Gruyter. p. 468. ISBN 9783110164237. p. 468.

- ↑ Steinacher 2010, pp. 359–360.

- ↑ Heather, Peter (2007). The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195325416. p. 469.

- ↑ Angelov 2018, p. 715. "Heruli. Germanic tribe with possible origins in Scandinavia..

- ↑ Green, D. H. (2000). Language and history in the early Germanic world. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521794234. p. 131

- ↑ Speidel, Michael P. (2004). Ancient Germanic Warriors: Warrior Styles from Trajan's Column to Icelandic Sagas. Routledge. ISBN 1134384203. p. 44.

- ↑ Bhim Singh Dahiya, Jats the Ancient Rulers (A clan study)/Appendices/Appendix II, p.329

- ↑ Bhim Singh Dahiya, Jats the Ancient Rulers (A clan study)/Appendices/Appendix II, p.329

- ↑ A glossary of the Tribes and Castes of the Punjab and North-West Frontier Province By H.A. Rose Vol II/H,p.327

- ↑ Jat History Dalip Singh Ahlawat/Parishisht-I, s.n. ह-25

- ↑ O.S. Tugania:Jat Samuday ke Pramukh Adhar Bindu,p.64,s.n. 2566

- ↑ Ram Swarup Joon: History of the Jats/Chapter V,p. 90

- ↑ A glossary of the Tribes and Castes of the Punjab and North-West Frontier Province By H.A. Rose Vol II/J,p.376

- ↑ Jordanes (1908). The Origins and Deeds of the Goths. Translated by Mierow, Charles C. Princeton University Press. p. III (23).

- ↑ Procopius (1914). History of the Wars. Translated by Dewing, Henry Bronson. Heinemann. Book VI, XV

- ↑ Procopius (1914). History of the Wars. Translated by Dewing, Henry Bronson. Heinemann. Book VI, XV

- ↑ Steinacher 2017, pp. 148–152.

- ↑ Goffart, Walter (2006). Barbarian Tides: The Migration Age and the Later Roman Empire. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812239393. pp. 205–209.

- ↑ Ellegård, Alvar (1987). "Who were the Eruli?". Scandia. 53.

- ↑ Heather, Peter (2010). Empires and Barbarians: The Fall of Rome and the Birth of Europe. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199892266. p. 116.

- ↑ Heather 2010, p. 124.

- ↑ Steinacher 2017, pp. 55–66.

- ↑ Steinacher 2010, pp. 322–327.

- ↑ Steinacher 2017, pp. 58–60.

- ↑ Steinacher 2010, p. 324.

- ↑ Steinacher 2017, p. 62.

- ↑ Zahariade, Mihail (2010), "A Crux in Bellum Scythicum. The Invasion of 267: Gothi or Heruli?", Antiquitas istro-pontica : Mélanges d'archéologie et d'histoire ancienneofferts à Alexandru Suceveanu,

- ↑ Steinacher 2017, pp. 63–65; Steinacher 2010, pp. 326–327.

- ↑ Green 2000, p. 1.

- ↑ Heather 1994, p. 87.

- ↑ Green 2000, p. 137.

- ↑ Green 2000, p. 1.

- ↑ Heather 1994, p. 87.

- ↑ Steinacher 2017, pp. 77–80.

- ↑ Steinacher 2017, pp. 77–80.

- ↑ Jordanes 1908, p. XXIII (116).

- ↑ Heather 1994, p. 33.

- ↑ Ellegård 1987.

- ↑ Steinacher 2010, p. 328.

- ↑ Steinacher 2017, p. 67.

- ↑ Goffart, Walter (2006). Barbarian Tides: The Migration Age and the Later Roman Empire. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812239393. p. 206.

- ↑ Halsall, Guy (2007). Barbarian Migrations and the Roman West, 376–568. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107393325. p. 260.

- ↑ Steinacher 2017, pp. 69–73.

- ↑ Steinacher 2017, p. 74.

- ↑ Steinacher 2010, p. 330.

- ↑ Steinacher 2010, p. 329.

- ↑ Goffart 2006, Ch.5.

- ↑ Heather 2010, p. 208.

- ↑ Steinacher 2010, p. 340.

- ↑ Heather 2010, p. 242.

- ↑ Steinacher 2010, p. 340.

- ↑ Steinacher 2010, p. 341

- ↑ Steinacher 2010, p. 338-345.

- ↑ Steinacher 2010, p. 347.

- ↑ Heather 2010, p. 251.

- ↑ Sarantis, Alexander (2010). "The Justinianic Herules". In Curta, Florin (ed.). Neglected Barbarians. ISD. ISBN 9782503531250. p. 366.

- ↑ Goffart 2006, pp. 205–209.

- ↑ Heather 2010, p. 430.

- ↑ Procopius 1914, Book VI, XV

- ↑ Heather 2010, p. 242.

- ↑ Steinacher 2017, p. 144.

- ↑ Steinacher 2010, p. 350.

- ↑ Steinacher 2017, pp. 144–145.

- ↑ Sarantis 2010, p. 369.

- ↑ Steinacher 2010, pp. 350–351

- ↑ Steinacher 2010, pp. 351–352.

- ↑ Sarantis 2010, p. 372.

- ↑ Goffart 2006, p. 209.

- ↑ Heather 2010, p. 225.

- ↑ Goffart 2006, p. 209.

- ↑ Sarantis 2010, pp. 393–397.

- ↑ Steinacher 2010, pp. 354–355

- ↑ Heather 1998, p. 109.

- ↑ Sarantis 2010, p. 385.

- ↑ Sarantis 2010, p. 402.

- ↑ Steinacher 2010, p. 355.

- ↑ Heather 2010, p. 240.

- ↑ Green 2000, p. 321.

Back to The Ancient Jats