Elam

| Author: Laxman Burdak, IFS (R). |

- For village of this name see Elam Shamli

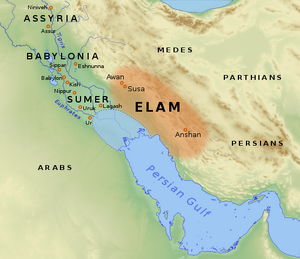

Elam (Hindi:एलम, Persian: تمدن ایلام) is one of the oldest recorded civilizations, centered in the far west and southwest of modern-day Iran (Ilam Province and the lowlands of Khuzestan). It lasted from around 2700 BC to 539 BC. It was preceded by what is known as the Proto-Elamite period, which began around 3200 BC when Susa (later capital of Elam) began to be influenced by the cultures of the Iranian plateau to the east. [1]

Variants of name

- Elam (Anabasis by Arrian, p. 364.)

- Elymais (Anabasis by Arrian, p. 364.)

- Elymais (Pliny.vi.28)

- Atamti

- Elamite

- Elamite Empire

- Haltamti

- Hujiyā - The Achaemenid Old Persian term for Elam was Hujiyā

- Ilam

- Ilam Province

- Elymaei (Pliny.vi.39)

- Elamites

- Elymaeans

- Elymais - Hellenic form of the more ancient name, Elam

- Elamitæ/ Elamitae (Pliny.vi.32)

Jat Places Namesake

- Elam = Elymais (Pliny.vi.28)

Jat Places Namesake

- Elam = Elam (Anabasis by Arrian, p. 364.). Elam is a Jat village in Shamli tahsil in district Shamli in Uttar Pradesh.

- Elam = Elymais (Anabasis by Arrian, p. 364.). Elam is a Jat village in Shamli tahsil in district Shamli in Uttar Pradesh.

Location

Ancient Elam lay to the east of Sumer and Akkad (modern-day Iraq). In the Old Elamite period, it consisted of kingdoms on the Iranian plateau, centered in Anshan, and from the mid-2nd millennium BC, it was centered in Susa in the Khuzestan lowlands. Its culture played a crucial role in the Persian Empire, especially during the Achaemenid dynasty that succeeded it, when the Elamite language remained in official use. The Elamite period is considered a starting point for the history of Iran (although there were older civilizations in Iranian plateau, like the Mannaeans kingdom in Iranian Azarbaijan and Shahr-i Sokhta (Burned City) in Zabol, and the newly discovered Jiroft civilization to the east. The Elamite language was not related to any Iranian languages, but may be part of a larger group known as Elamo-Dravidian. [1]

Elam gives its name to one of the provinces of modern Iran (usually spelt Ilam). [1]

Etymology

The Elamites called their country Haltamti[2] (in later Elamite, Atamti), which the neighboring Akkadians rendered as Elam. Elam means "highland". Additionally, the Haltamti are known as Elam in the Hebrew Old Testament, where they are called the offspring of Elam, eldest son of Shem (see Elam in the Bible).

The high country of Elam was increasingly identified by its low-lying later capital, Susa. Geographers after Ptolemy called it Susiana. The Elamite civilization was primarily centered in the province of what is modern-day Khuzestan, however it did extend into the later province of Fars in prehistoric times. In fact, the modern provincial name Khuzestān is derived from the Old Persian root Hujiyā, meaning "Elam". [3]

History

Knowledge of Elamite history remains largely fragmentary, reconstruction being based on mainly Mesopotamian sources. The city of Susa was founded around 4000 BC, and during its early history, fluctuated between submission to Mesopotamian and Elamite power. [1]

The earliest levels (22-17 in the excavations conducted by Le Brun, 1978) exhibit pottery that has no equivalent in Mesopotamia, but for the succeeding period, the excavated material allows identification with the culture of Sumer of the Uruk period. Proto-Elamite influence from the Persian plateau in Susa becomes visible from about 3200 BC, and texts in the still undeciphered Proto-Elamite writing system continue to be present until about 2700 BC. The Proto-Elamite period ends with the establishment of the Awan dynasty. The earliest known historical figure connected with Elam is the king Enmebaragesi of Kish (c. 2650 BC?), who subdued it, according to the Sumerian king list. However, real Elamite history can only be traced from records dating to beginning of the Akkadian Empire in around 2300 BC onwards. [1]

The earliest levels (22-17 in the excavations conducted by Le Brun, 1978) exhibit pottery that has no equivalent in Mesopotamia, but for the succeeding period, the excavated material allows identification with the culture of Sumer of the Uruk period. Proto-Elamite influence from the Persian plateau in Susa becomes visible from about 3200 BC, and texts in the still undeciphered Proto-Elamite writing system continue to be present until about 2700 BC. The Proto-Elamite period ends with the establishment of the Awan dynasty. The earliest known historical figure connected with Elam is the king Enmebaragesi of Kish (c. 2650 BC?), who subdued it, according to the Sumerian king list. However, real Elamite history can only be traced from records dating to beginning of the Akkadian Empire in around 2300 BC onwards. [1]

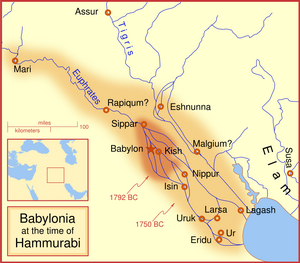

The Old Elamite period began around 2700 BC. Historical records mention the conquest of Elam by Enmebaragesi of Kish. Three dynasties ruled during this period. We know of twelve kings of each of the first two dynasties, those of Awan (or Avan; c. 2400–2100 BC) and Simash (c. 2100–1970 BC), from a list from Susa dating to the Old Babylonian period. Two Elamite dynasties said to have exercised brief control over Sumer in very early times include Awan and Hamazi, and likewise, several of the stronger Sumerian rulers, such as Eannatum of Lagash and Lugal-anne-mundu of Adab, are recorded as temporarily dominating Elam. [1]

The Avan dynasty was partly contemporary with that of Sargon of Akkad, who not only defeated the Awan king Luhi-ishan and subjected Susa, but attempted to make Akkadian the official language there. From this time, Mesopotamian sources concerning Elam become more frequent, since the Mesopotamians had developed an interest in resources (such as wood, stone and metal) from the Iranian plateau, and military expeditions to the area became more common. [1]

However, with the collapse of Akkad under Sargon's great-grandson, Shar-kali-sharri, Elam declared independence under the last Avan king, Kutik-Inshushinak (c. 2240-2220 BC), and threw off the Akkadian language, promoting in its place the brief Linear Elamite script. [1]

Kutik-Inshushinnak conquered Susa and Anshan, and seems to have achieved some sort of political unity. Following his reign, the Awan dynasty collapsed as Elam was temporarily overrun by the Guti. [1]

About a century later, Shulgi of Ur retook the city of Susa and the surrounding region. During the first part of the rule of the Simashki dynasty, Elam was under intermittent attack from Mesopotamians and Gutians, alternating with periods of peace and diplomatic approaches. Shu-Sin of Ur, for example, gave one of his daughters in marriage to a prince of Anshan. But the power of the Sumerians was waning; Ibbi-Sin in the 21st century did not manage to penetrate far into Elam, and in 2004 BC, the Elamites, allied with the people of Susa and led by king Kindattu, the sixth king of Simashk, managed to sack Ur and lead Ibbi-Sin into captivity -- thus ending the third dynasty of Ur. However, the kings of Isin, successor state to Ur, did manage to drive the Elamites out of Ur, rebuild the city, and to return the statue of Nanna that the Elamites had plundered. [1]

Jat History

Migration to India

Mangal Sen Jindal[4] has mentioned that disaster struck on about 2006 BC, when Elamites from the highlands to the last the destroyed the city. The Sumerians were never again a dominant element politically, but their culture persisted as the foundation for all subsequent civilizations in the Tigris Euphrates valley. [5]

He[6] writes that from above quotations, we must infer that after the fall of Elam kingdom, the Jats of that kingdom migrated into India and some of them during the course of time, migrated to the Elam village in district Muzaffarnagar (now Shamli) in Uttar Pradesh. Elam on Shahadra- Saharanpur route is an important and very-well-to-do Jat village. This name is after their old kingdom in Persia as Baraut (Barot) in Meerut District is named after Broach on River Narmada near Surat and Barod (Baroda), the area from where the Jats of this town migrated.

Manda Empire: Bhim Singh Dahiya[7] writes ..... Assurbanipal died in 626 BC, and his successors were disputing the throne. Such an opportunity was not to be lost and second attack of Nineveh began. The Assyrian Emperor burnt himself in his palace and perished with his family. Thus in 606 BC, Nineveh fell and so utter was its ruin that the Assyrian name was forgotten and the history of their empire soon melted into fable. [8] Armenia and Cappadocia were including in the Manda Empire. Lydia was emerging as a powerful nation in the west and it was inevitable that the two powers should collide. The war began but in 585 BC, when there was a total eclipse of the sun; and it was stopped after six years of fighting, under a peace treaty. A daughter of the Lydian emperor was married to the heir apparent of Manda, and the kingdom Urartu was annexed to Manda empire. Next year, i.e. 584 BC, this great emperor died. Thus, from a beaten nation he raised the Mandas into the most powerful and virile empire of that time. It is aptly stated that the east was Semitic when he began to rule but it was Aryan when he stopped. This leader in one of the great moments in history was succeeded by Ishtuvegu, Astyages of the Greeks. He was an unworthy son of a worthy father, and he deviated from the basic policy of the Mandas, i.e. to keep fit and ready for war. He had no son and his daughter named Mandani (after the clan name) was married to a small vassal prince of Elam.

Elymais

Elymais or Elamais (Ἐλυμαΐς, Hellenic form of the more ancient name, Elam) was an autonomous state of the 2nd century BC to the early 3rd century AD, frequently a vassal under Parthian control. It was located at the head of the Persian Gulf in Susiana (the present-day region of Khuzestan, Iran).[9] Most of the population probably descended from the ancient Elamites,[10] who once had control of that area.

The Elymaeans were reputed to be skilled archers. In 187 BC, they killed Antiochus III the Great after he had pillaged their temple of Bel. Nothing is known of their language, even though Elamite was still used by the Achaemenid Empire 250 years before the kingdom of Elymais came into existence.[11] A number of Aramaic inscriptions are found in Elymais.[12]

Mention by Pliny

Pliny[13] mentions Arabia.... Lying in the interior, and joining up to the Atramitæ, are the Mitæi; are the Minæ; the Elamitæ41 dwell on the sea-shore, in a city from which they take their name.

41 Hardouin is doubtful as to this name, and thinks that it ought to be Elaitæ, or else Læanitæ, the people again mentioned below.

Mention by Pliny

Pliny[14] mentions The Persian And The Arabian Gulfs. ....Here Persis begins, at the river Oratis13, which separates it from Elymais.14 Opposite to the coast of Persis, are the islands of Psilos, Cassandra, and Aracia, the last sacred to Neptune15, and containing a mountain of great height. Persis16 itself, looking towards the west, has a line of coast five hundred and fifty miles in length; it is a country opulent even to luxury, but has long since changed its name for that of "Parthia."17 I shall now devote a few words to the Parthian empire.

13 Now the Tab, falling into the Persian Gulf.

14 A district of Susiana, extending from the river Euleus on the west, to the Oratis on the east, deriving its name perhaps from the Elymæi, or Elymi, a warlike people found in the mountains of Greater Media. In the Old Testament this country is called Elam.

15 Ptolemy says that this last bore the name of "Alexander's Island."

16 Persis was more properly a portion only or province of the ancient kingdom of Persia. It gave name to the extensive Medo-Persian kingdom under Cyrus, the founder of the Persian empire, B.C. B.C. 559.

17 The Parthi originally inhabited the country south-east of the Caspian, now Khorassan. Under Arsaces and his descendants, Persis and the other provinces of ancient Persia became absorbed in the great Parthian empire. Parthia, with the Chorasmii, Sogdii, and Arii, formed the sixteenth satrapy under the Persian empire. See c. 16 of this Book.

Mention by Pliny

Pliny[15] mentions Tigris...Below31 this district is Susiane, in which is the city of Susa32, the ancient residence of the kings of Persia, built by Darius, the son of Hystaspes; it is distant from Seleucia Babylonia four hundred and fifty miles, and the same from Ecbatana of the Medi, by way of Mount Carbantus.33 Upon the northern channel of the river Tigris is the town of Babytace34, distant from Susa one hundred and thirty-five miles. Here, for the only place in all the world, is gold held in abhorrence; the people collect it together and bury it in the earth, that it may be of use to no one.35 On the east of Susiane are the Oxii, a predatory people, and forty independent savage tribes of the Mizæi.

Above these are the Mardi and the Saitæ, subject to Parthia: they extend above the district of Elymais, which we have already mentioned36 as joining up to the coast of Persis. Susa is distant two hundred and fifty miles from the Persian Sea.

31 More to the south, and nearer the sea.

32 Previously mentioned in c. 26.

33 A part of Mount Zagrus, previously mentioned, according to Hardouin.

34 Its site appears to be unknown. According to Stephanus, it was a city of Persia. Forbiger conjectures that it is the same place as Badaca, mentioned by Diodorus Siculus, B. xix. c. 19; but that was probably nearer to Susa.

35 The buryer excepted, perhaps.

36 In c. 28 of the present Book.

Mention by Pliny

Pliny[16] mentions Tigris... Below the Eulæus is Elymais44, upon the coast adjoining to Persis, and extending from the river Orates45 to Charax, a distance of two hundred and forty miles. Its towns are Seleucia46 and Socrate47, upon Mount Casyrus. The shore which lies in front of this district is, as we have already stated, rendered inaccessible by mud,48 the rivers Brixa and Ortacea bringing down vast quantities of slime from the interior,—Elymais itself being so marshy that it is impossible to reach Persis that way, unless by going completely round: it is also greatly infested with serpents, which are brought down by the waters of these rivers.

44 Previously mentioned in c. 28.

45 The modern Tab.

46 Now called Camata, according to Parisot.

47 The modern Saurac, according to Parisot. The more general reading is "Sosirate."

48 Our author has nowhere made any such statement as this, for which reason Hardouin thinks that he here refers to the maritime region mentioned in c. 29 of the present Book (p. 69), the name of which Sillig reads as Ciribo. Hardouin would read it as Syrtibolos, and would give it the meaning of the "muddy district of the Syrtes." It is more likely, however, that Pliny has made a slip, and refers to something which, by inadvertence, he has omitted to mention.

External links

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elam

- ↑ Kent, Roland (1953). Old Persian: Grammar, Texts & Lexicon. American Oriental Series. 33). American Oriental Society. p. 53. ISBN 0-940490-33-1.

- ↑ Kent, Roland (1953). Old Persian: Grammar, Texts & Lexicon. American Oriental Series. 33). American Oriental Society. p. 53. ISBN 0-940490-33-1.

- ↑ Mangal Sen Jindal (1992): History of Origin of Some Clans in India (with special Reference to Jats), Page-55, Sarup & Sons, 4378/4B, Ansari Road, Darya Ganj, New Delhi-110002 ISBN 81-85431-08-6

- ↑ Civilization past and present, Page 19, American Library, New Delhi

- ↑ Mangal Sen Jindal (1992): History of Origin of Some Clans in India (with special Reference to Jats), Page-56, Sarup & Sons, 4378/4B, Ansari Road, Darya Ganj, New Delhi-110002 ISBN 81-85431-08-6

- ↑ Bhim Singh Dahiya, Jats the Ancient Rulers, p. 131

- ↑ Bhim Singh Dahiya, Jats the Ancient Rulers, p. 130

- ↑ Hansman, John F. "ELYMAIS". Encyclopædia Iranica

- ↑ Hansman, John F. "ELYMAIS". Encyclopædia Iranica

- ↑ G. Cameron Persepolis Treasury Tablets (1948), and R. Hallock, Persepolis Fortification Tablets (1969).

- ↑ Gzella, H. (2008) Aramaic in the Parthian Period: The Arsacid Inscriptions. In Gzella, H. & Folmer, M.L. (Eds.) Aramaic in its Historical and Linguistic Setting. Wiesbaden. P. 107-130

- ↑ Natural History by Pliny Book VI/Chapter 32

- ↑ Natural History by Pliny Book VI/Chapter 28

- ↑ Natural History by Pliny Book VI/Chapter 31

- ↑ Natural History by Pliny Book VI/Chapter 31

Back to Jat Places in Iran