Jats in Islamic History

| Author of this article is Laxman Burdak लक्ष्मण बुरड़क |

The Jat people and Meds have been the oldest occupants of Sind. The first Persian account of the 11th century Mujmal ut-Tawarikh (1026), originally an ancient work in Sanskrit, mentions Jats and Meds as the ancient tribe of Sind and calls them the descendants of Ham, the son of Noah.[1][2]The Ghaznavid poet, Farrukhi calls the Jats (Zatt in Arabic) as the Indian race.[3] These Arabic/Persian accounts find support from the early fifth century inscription which documented the Indianized names of the Jat rulers,[4] such as Raja Jit-Jit Salindra-Devangi-Sumbooka-Degali-Vira Narindra- Vira Chandra and Sali Chandra. Furthermore, the Mujmal ut-Tawarikh also mentions the Indianized name of one of their chiefs of the Jats in remote ancient time as Judrat.[5][2]These textual references further strengthened the view of O'Brien, who opines that the names and traditions of certain Jat tribes seem to connect them more closely with Hindustan.[6]

History

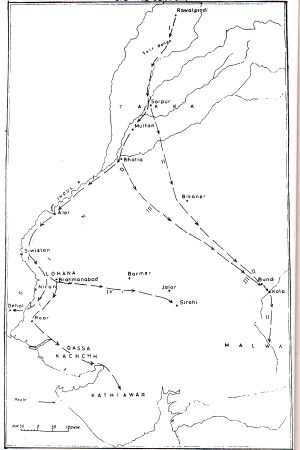

According to Dr. Raza, Jats appear to be the original race of Sind valley, stretching from the mouth of Indus to as far as the valley of Peshawar.[2]Traditionally Jats of Sind consider their origin from the far northwest and claimed ancient Garh Gajni (modern Rawalpindi) as their original abode.[7] Persian chronicler Firishta strengthened this view and informs us that Jats were originally living near the river of the Koh-i-Jud (Salt Range) in northwest Punjab.[8] The Jats then occupied the Indus valley and settled themselves on both the banks of the Indus River. By the fourth century region of Multan was under their control.[2]Then they rose to the sovereign power and their ruler Jit Salindra, who promoted the renown of his race, started the Jat colonisation in Punjab and fortified the town Salpur/Sorpur, near Multan.[9]

Ibn Hauqual mentions the area of their abode in between Mansura and Makran.[10] By the end of seventh century, Jats were thickly populated in Deybal region.[11] In the early eighth century, when the Arab commander Muhammad bin Qasim came to Sind, the Jats were living along both sides of the river Indus. Their main population was settled in the lower Sind, especially in the region of Brahmanabad (Mansura); Lohana (round the Brahmanabad) with their two territories Lakha, to the west of Lohana and Samma, to the south of Lohana; Nerun (modern Hyderabad); Dahlilah; Roar and Deybal. In the further east, their abode also extended in between Deybal, Kacheha (Qassa) and Kathiawar in Gujarat. In upper Sind they were settled in Siwistan (Schwan) and Alor/Aror region.[2][12]

In the 7th century, the Chinese traveler Xuanzang reported that: "in a district of slopes and marshes to more than a thousand li beside the Sindhu River there live several hundred, nearly a thousand, families of ferocious people who made slaughtering their occupation and sustain themselves by rearing cattle, without any other means of living. All the people, whether male of female, and regardless of nobility or lowliness, shave off their hair and beards and dress in religious robes, thus giving the appearance of being bhikṣus (and bhikṣunīs), yet engaging in secular affairs."[13] Earlier translators of this same passage gave differing accounts of the numbers of people, however. Beal says that "there are several hundreds of thousands families settled in Sind"[14], while Watters says there were "some myriads of families"[15]

Dr. Raza proposes that these unnamed people were Jats.[16] The Chachnama, possibly dating originally to the 7th or 8th century CE, and translated into Persian in 1216 CE, stratified these people into 'the western Jats' (Jatan-i-gharbi) and 'the eastern Jats (Jatan-i-Sharqi),[17] living on the eastern and western side of the Indus River.

Before the invasion of Sultan Mahmud (1027), Jats had firmly established in the region of Multan and Bhatiya on the banks of Indus River.[2][18] Alberuni mentions the Mau as the abode of Jats in Punjab, situated in between the river Chenab and Beas.[19]

In the 13th century CE, chroniclers further classified them as 'The Jats living on the banks of the rivers (Lab-i-daryayi)[20] and the Jats living in plain,desert (Jatan-i-dashti); and 'the rustic Jats' (rusta'i Jat) living in villages.[21] Professionally, they were classified on the basis of their habitats, as boatmen and maker of boats, those who were living in the riverside.[22] However Jats of country side were involved in making of swords; as the region of Deybal was famous for the manufacture of swords, and the Jats were variously called as teghzan (holder of the swords).[23] The rustic people were appointed by the Chach and the Arab commanders as spies (Jasus) and the caravan guide (rahbar). They used to guide the caravans on their way both during day time and at night.[24][2]

In political hierarchy, the early fifth century inscription refers to them as a ruler of Punjab, part of Rajasthan and Malwa.[2]It further highlights their sovereign position with high sounded epithets such as Sal, Vira, and Narpati ('lord of men').[25] In the military hierarchy, the Chachnama placed them high on the covetous post of Rana. During the war they were brought against enemy as soldiers. In Dahir's army all the Jats living in the east of Indus River stood marshalled in the rear against the Arab commander Muhammad Bin Qasim.[26] They were also involved in palace management, thus Chach appointed them as his bodyguard (pasdar).[27]

Migration Jats from Sind

As for the migration of Jats from Sind, it may be assumed that natural calamity and increase in population compelled them to migrate from their original abode in search of livelihood.[2]Hoernle has propounded the 'wedge theory' for the migration of most of the ancient tribes. This wedge theory tends us to believe that the Jats were among the first wave of the Aryans, and their first southeast migration took place from the North-West, and established their rule at Sorpur in Multan regions. Further they migrated towards east and stretched their abode from Brahmanabad (Mansura) to Kathiawar. As Jataki, the peculiar dialect of the Jats, also proves that the Jats must have come from the NW Punjab and from other districts (e.g. Multan) dependent upon the great country of the Five rivers.[28]

By the end of fifth and the beginning of the sixth century, their southward migration, second in line, took place and they reached Kota in Rajasthan, probably via Bikaner regions. From Kota they migrated further east and established their rule at Malwa under the rule of Salichandra, son of Vira Chandra. Salichandra erected a minster (mindra) on banks of the river Taveli in Malwa.[29] Probably after their defeat by Sultan Mahmud in 1027 AD, and later hard pressed by the Ghaznavi Turkish Commander, the Jats of Sind again migrated to Rajasthan and settled themselves in Bundi regions.[2]The second inscription found at Bundi probably dates from circa samvat 1191 (1135 AD) possibly refers to the Jats as opponents of the Parmara rulers of Rajasthan.[30]

When Muhammad bin Qasim attacked Dahlilah, a fortified town in between Roar and Brahmanabad, most of the inhabitants (the Jats) had abandoned the place and migrated to Rajasthan via desert and took shelter in the country of Siru (modern Sirohi) which was then ruled by King Deva Raj, a cousin of Rai Dahir.[31] However, the third migration took place in early eighth century and Jats of lower Sind migrated to Rajasthan, probably via Barmer regions. By the twelfth century, the Jats settled in western Punjab, as the native poet Abul Farj Runi mentions them along with the Afghans.[2]Meanwhile, they also extended their abode in the eastern part of the Punjab (now Haryana), as in the end of the twelfth century they resisted Qutab Din Aibek in the region of Hansi.[32]

The Jats of the lower Indus comprise both Jats and Rajputs, and the same rule applies to Las-Bela where descendants of former ruling races like the Sumra and the Samma of Sind and the Langah of Multan are found. At the time of the first appearance of the Arabs they found the whole of Makran in possession of Zutts.[33] On phronetic grounds, this maybe Jats.[34]

According to a Hadith, Abdulla Bin Masood, a companion of the Islamic prophet Muhammad saw some strangers with Muhammad and said that their features and physique were like those of Jats.[35] This indicates that Jats may have been in Arabia even during Muhammad's time. It is mentioned in the Abadis i.e., the authentic traditions of Mohammad compiled by Imam Bukhari (d. 875 A.D - 256 A.H) that an Indian tribe of had settled in Arabia before Mohammad’s times . Bukhari also tells us that an Indian Raja (king) sent a jar of ginger pickles to Muhammad. This shows that the Indians resided in an adjacent area.[36] Further writing about the period of the Companions in his book "Al adab al Mufarrad" has stated that once when Aisha (Muhammads's wife) fell ill, her nephews brought a Jat doctor for her treatment. We hear of them next when the Arab armies clashed with the Persian forces which were composed of Jat soldiers as well. The Persian Command Hurmuz used Jat soldiers against Khalid ibn al-Walid in the battle of 'salasal' of 634 A.D (12 hijri). This was the first time that Jats were captured by the Arabs. They put forward certain conditions for joining the Arab armies which were accepted, and on embracing Islam they were associated with different Arab tribes.[37] This event proves that the first group of people from the Indian subcontinent to accept Islam were Jats who did it as early as 12 hijri (634 A.D) in the time of `Umar ibn al-Khattāb.[38]

The Persian King Yazdgerd III had also sought the help of the Sind ruler who sent Jat soldiers and elephants which were used against the Arabs in the Battle of al-Qādisiyyah .

According to Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari (Tabari), Ali ibn Abi Talib A.S had employed Jats to guard Basra treasury during the battle of Jamal. Template:Cquote[39] Amir Muawiya had settled them on the Syrian border to fight against the Romans. It is said that 4,000 Jats of Sind joined Mohammad Bin Qasim's army and fought against Raja Dahir. Sindhi Jats henceforth began to be regularly recruited in the Muslim armies.

The line of ruler ship before Islam runs: Siharus, Raja Sahasi II, Chach, Raja Dahir. The first two were Buddhist and the last two Hindu Brahmins. There is a difference of opinion among historians concerning the social dynamic between the Jatts and the Brahmins.Some historians suggest that the relationship was an adversarial one, with Brahmins using their high caste status to exploit and oppress the Jatts, Meds and Buddhists, who formed the bulk of the peasantry.[40] According to a quote by historian U.T Thakkur, "When Chach, the Brahmim chamberlain who usurped the throne of King Sahasi II went to Brahmanabad, he enjoined upon the Jats and Lohanas not to carry swords, avoid velvet or silken cloth, ride horses without saddles and walk about bare-headed and bare-footed".[41]

However, Thakkur also writes that Hinduism and Buddhism existed side by side, suggesting a more complex dynamic between the endogamous groups. [The king followed early Hindusim, but a majority of his advisers were a mix of Buddhists,and other faiths. The ruler of Brahmanabad, a Jatt, also had professed Buddhism as his spiritual guide. Nonetheless, there was a strong sense of "ideological dualism" between them, which he wrote was the inherent weakness that the Arabs exploited in their favor when they invaded the region.[41]

It was because of this internal dissension that that Muhammad bin Qasim received cooperation from some of the Buddhists as well as some of the Jats and Meds during his campaign in Sind [3](An advanced history of India by Ramesh Chandra Majumdar; Hemchandra Raychaudhuri; Kalikinkar Datta Delhi: Macmillan India, 1973) In fact he was hailed as deliverer by several sections of local population. The position of the Buddhists in Sind seeking support from outside can be read in the Chach Nama.

Mohammad Bin Qasim's work was facilitated by the treachery of certain Buddhist priests and renegade chiefs who deserted their sovereign and joined the invader. With the assistance of some of these traitors, Mohammad crossed the vast sheet of water separating his army from that of Dahir and gave battle to the ruler near Raor (712 A.D.). Dahir was defeated and killed|30px|30px|Historical accounts documented in the |Chach Nama according to Ramesh Chandra Majumdar, Hemchandra Raychaudhuri, & Kalikinkar Datta[42]

Sind had a large Buddhist population at this time but the ruler, Dahir, followed Brahminism, and to the Arabs was a Brahmin. It is said that the Buddhists been receiving constant information from their co-religionists in Afghanistan and Turkistan about the liberal treatment meted out to them by the Arab conquerors of those regions.[43] Thus, bin-Qasim received cooperation from the Buddhist population.[44] The Buddhist ruler of Nerun (Hyderabad) had secret correspondence with Muhammad Bin Qasim. Similarly, Bajhra and Kaka Kolak, Buddhist Rajas of Sewastan, allied themselves with Muhammad Bin Qasim.[45]

Taqwin al-Buldan observed that in the ancient period the Jats were also found in Baluchistan in a large number in addition to Sind [46] But he did not agree with those historians, [47] who traced their origin to the Middle East and treated this region as their native place. [48] He fully supports Maulana Sayyed Sulaiman Nadvi, the distinguished disciple of Allama Shibli Nomani and the author of a scholarly work on the Indo Arab relations (Arab wa Hind ke Toalluqat) that during the occupation of Sind and Baluchistan by the Persian Kings (Chosroes), the Jats of this region came to be employed in Persia or Iran in army and state administration. [49] He considered it an established fact that the Jats originally belonged to India but it could not be denied that in course of time a large number of them had settled in other parts of Asia for different purposes. [50]

It is quite evident from the account of the Arab geographers, particularly Ibn Khurdazbeh, that their population was mainly concentrated in Makran, Baluchistan, Multan and Sind and that for about thousand miles from Makran to Mansurah the whole passage was inhabited by them. Moreover, on this long route they rendered great service to the travellers as huffaz al-tariq or road-guards. [51] In the same way, Al Istakhari, the author of an important geographical work Al-Masalik wal-Mamalik, had stated that the whole region from Mansura to Multan was full of the Jats. [52] , [53] In view of Quzi Athar Mubarakpuri, it was form these places that many Jats had migrated to Persia and different parts of Arab and settled there long ago. [54], [55]

Jat settlements in Islamic countries

Giving an account of the Jats’ settlement in Persia, Qazi Athar Mubarakpuri had stated that they had been living in this region since a long time and they had developed many big and flourishing towns of their own as we are informed by Ibn-i-Khurdazbeh (d.893AD) that at about sixty miles away from the city of Ahwaz, there is a big city of the Jats, which is known after them as al-Zutt. [56] Another geographer of the same period had also observed that in the vicinity of Khuzistan there was a grand city Haumat al-Zutt. [57] These evidences given by the eminent author are enough to suggest that the Jats who settled in Persia gradually built up their economic resources and made significant contribution to urbanization of that country. [58]

The studies of Quzi Athar Mubarakpuri also bring to light that the Jats did not remain confined to Persia. They got settlement in different Parts of Arab land, which was under the Persian rule in those days. The Arab geographers testified that fact that in the coastal region of the Persian Gulf from Ubullah to Bahrain they had many pockets of their population and that they engaged themselves in different kind of work including cattle breeding. [59], [60] It is also confirmed by the Arab historians that in pre Islamic period their largest concentration was found in Ubullah, a fertile and pleasant place near the city of Basrah. Their second big settlement was in Bahrain where they had been residing in large numbers prior to the period of Muhammad as we are informed by Al-Baladhuri and other historians [61] In the same way, there are clear evidences for their settlement in Yemen before the advent of Islam and their important role in socio- political life of those days Yemen. In the times of pious Caliphs when Persia and many parts of the Arab region (previously ruled by Persian and Roman Kings) came under the Muslim army and a number of them got converted to Islam also. It is confirmed by different historical and geographical works, as cited by Maulana Mubarakpuri that they had settled in large number in Antioc and coastal town of Syria under the patronage of the pious and Umayyad caliphate (Khilafat-e-Rashidah and Banu Umayyad) [62], [63]

A very important and useful information that comes forth through the researches of Maulana Mubarakpuri is that the people of Makkah and Madinah in the times of Muhammad were not only familiar with the Indians, the Jats were also well known to them. On the authority of Sirat-i-Ibn-i-Hisham, Maulana has stated that once some people came from Najran to Madinah. Looking at them, Muhammad asked who are they ? They are just like Indians. [64], [65]

These Indians were assumed to be Jats (Zutt). In the same way, it is recorded in Jami-i-Tirmezi, the well known collection of Hadith that the famous Sahabi Sazrat Abdullah Ibn Masood once saw some persons in the company of Muhammad in Makkah, he observed that their hair and body structure is just like the Jats. There are also some other references in the Arabic source to the existence of the Jats in Madinah in that period. They also included a physician (Tabib) who was once consulted during the illness of Aisha, the wife of Muhammad. [66]

Socio-cultural impact of Jats on Arabians

It also appears from authentic sources that the Jats not only lived in different parts of the Arab Land, they also observed their social customs and traditions in their daily life and that the local people got influenced by them in different ways as the studies of Qazi Ather Mubarakpuri show. [67], [68]

Some Arab writers have referred to the Jats peculiar style of hair cut which had been adopted by some Arabs. [69] In the same way some special clothes were known after them and so called al-Thiyab al-zuttia (Jats cloths), which were available in the Arab Markets. [70] But our author is not quite sure that whether the Jats prepared these clothes or these were part of their special dress like dhoti.[71] Moreover, the learned author has also come to the conclusion, in the light of some references in the Arabic poetical works, that certain form of Indian song were known of the Arabs since the ancient period and these were most probably introduced by the Jats as this was called Song of Jats (Ghina al –Zutt) [72] These points are enough to suggest that the Jats were fully free in the Arab lands to follow and observe the customs and tradition of their native land. This is also supported by the fact that the Jats who had been living in the places around Basrah continued to talk in their original language at least up to the period of the pious caliphs. We are informed by the author of Majma al-Bahrain that they had once spoken even to the fourth caliph Ali in their own language. [73] , [74]

It is very interesting that we come to know through the studies of Maulana Mubarakpuri that the Jats residing in Bahrain, Yemen and other coastal regions in a large number had influenced the local Arabs by their language to such extent that the latter lost the originality and eloquence of their language. For the same reason the language of the people of the tribes of Banu Abd Qais and Azd was declared to be diluted and unauthentic due to their mingling and frequent interaction with Persian and Indian people. [75], [76]

The studies of Quzi Athar Mubarakpuri give a clear impression that the Jats who had settled in different parts of the Persian and Arab land had left their socio-cultural impact on the local people [77] , [78]

See also

- Jats in Islamic History

- The Jats in the Chachnamah: Some Observations

- Socio-Political and Military Role of Jats in West Asia as Gleaned from Arabic Sources

- Qazi Athar Mubarakpuri's studies on Jats

References

- ↑ Mujmal ut-Tawarikh, Ed. Vol.I p. 104

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 Dr S.Jabir Raza, The Jats - Their Role and Contribution to the Socio-Economic Life and Polity of North and North West India. Vol I, 2004, Ed Dr Vir Singh Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "jabir" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "jabir" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "jabir" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "jabir" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "jabir" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "jabir" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "jabir" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "jabir" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "jabir" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Ibn Hauqal, Ed. Vol.I, p.40

- ↑ Inscription No.1, Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan. (1829-1832) James Tod and William Crooke, Reprint: Low Price Publications, Delhi (1990), Vol.II, Appendix. pp. 914-917.

- ↑ Mujmal ut-Tawarikh, Ed. Vol.I p. 104

- ↑ O'Brien, Multan Glossary, cited Ibbetson, op.cit., p. 105

- ↑ Elliot, op. cit., Vol.I, p.133

- ↑ Muhammad Qasim Hindu Shah Firista, Gulsan-i-Ibrahimi, commonly known as Tarikh-i-Firishta, Nawal Kishore edition, (Kanpur, 1865), Vol.I, p.35

- ↑ Inscription No.1, Tod, op.cit., Vol.II, Appendix pp. 914-917.

- ↑ Ibn Hauqal, Ed. Vol.I, p.40

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Islam, vol.II, p.488

- ↑ Chachnama, pp. 165-66; Alberuni, Qanun al-Mas'udi, in Zeki Validi Togan, Sifat al-ma'mura ala'l-Biruni; Memoirs of the Archeological Survey of India No. 53, pp.16,72; Abu Abudullah Muhammad Idrisi, Kitab Nuzhat-ul-Mustaq, Engl. translation by S.Maqbul Ahmad, entitled India and the Neighbouring Territories, (I. Eiden, 1960), pp.44,145

- ↑ Li, Rongxi. The Great Tang Dynasty Record of the Western Regions. Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research (1996), p. 346.

- ↑ Beal, Vol.II,p.273

- ↑ Watters, Thomas. On Yuan Chwang's Travels in India (A.D. 629-645). (1904-1905), Reprint: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers, New Delhi (1973), Vol. II, p. 252.

- ↑ Dr S.Jabir Raza, The Jats - Their Role and Contribution to the Socio-Economic Life and Polity of North and North West India. Vol I, 2004, Ed Dr Vir Singh

- ↑ Chachnama, pp.98, 117,131

- ↑ Zainul-Akhbar, p.191

- ↑ Sifat al-ma'mura ala'l-Biruni, p.30

- ↑ Zai'nul-Akhbar, p.191; Tarikh-i-Firishta, Vol.I,p.35

- ↑ Chachnama, pp.104,167

- ↑ Zai'nul-Akhbar, p.191; Tarikh-i-Firishta, Vol.I,p.35

- ↑ Ibn Hauqal, Ed. Vol.I, p.37, Chachnama pp.33,98

- ↑ Chachnama, pp.33,163

- ↑ Inscription No.1, Tod, op.cit., Vol.II, Appendix pp. 914-917.

- ↑ Chachnama, p. 133

- ↑ Chachnama, p.64

- ↑ Richard F. Burton, op. cit., p.246

- ↑ Inscription No.1, Tod, op.cit., Vol.II, Appendix pp. 914-917.

- ↑ Inscription No.II, Tod, op.cit., Vol.II, Appendix, pp. 917-919 and n. 13

- ↑ Chachnama, p.166

- ↑ Hasan Nizami, Tajul-ma'asir, Fascimile translation in ED, Vol. II, p.218

- ↑ Encyclopaedia of Islam

- ↑ Encyclopaedia of Islam

- ↑ (Arab~o-Hind ke Tallukat, By Suiaiman Nadvi)

- ↑ PN Oak: Some Blunders of Indian Historical Research]

- ↑ (Tareekh-e-Sind, Part I, By Ijaaul Haq Quddusi)

- ↑ http://punjabi.net/talk/messages/1/21319.html?1016680803

- ↑ (Dr. Mohammad Ishaque in Journal of Pakistan Historical Society Vol 3 Part1)

- ↑ (An Advanced History of India, Part II, By R.C. Majumdar, H.C. Roychandra and Kalikinkar Ditta)

- ↑ Jump up to: 41.0 41.1 (Sindhi Culture, by U.T Thakur Bombay 1959 )

- ↑ (An advanced history of India by Ramesh Chandra Majumdar; Hemchandra Raychaudhuri; Kalikinkar Datta Delhi: Macmillan India, 1973)

- ↑ [1](The Muslim community of the Indo-Pakistan subcontinent, 610-1947; a brief historical analysis by Ishtiaq Husain Qureshi)

- ↑ [2](The Muslim community of the Indo-Pakistan subcontinent, 610-1947; a brief historical analysis by Ishtiaq Husain Qureshi)

- ↑ link to the book(The Muslim community of the Indo-Pakistan subcontinent, 610-1947; a brief historical analysis by Ishtiaq Husain Qureshi

- ↑ Abul Fida , Taqwin al-Buldan Paris , 1840, p 334

- ↑ Abdul Malik Ibn Hisbam, Kitab al-Tijan, Hyderabad (n.d.) , p 222 (as cited by Qazi Athar, p 62

- ↑ Qazi Athar, op. cit. p.62

- ↑ Sayyed Sulaiman Nadvi, Arab wa Hind ka Taalluqat , Matba Maarif Azamgarh , 1992 , p.11; Qazi Athar , P.66)

- ↑ Zafarul Islam: Qazi Athar Mubarakpuri’s Studies on Jats, The Jats, Vol. II, Ed. Dr Vir Dingh, Delhi, 2006. p. 26

- ↑ Ibn Kburdazbeb, Al Masalik wal Mamalik, E.J.Brill, 1889, P. 56

- ↑ Al-Istakhari, Kitab-o-Masalik wal Mamalik , E.J. Brill , 1927 , P. 35

- ↑ Zafarul Islam: Qazi Athar Mubarakpuri’s Studies on Jats, The Jats, Vol. II, Ed. Dr Vir Dingh, Delhi, 2006. p.25-26

- ↑ Qazi Athar , pp. 62-63

- ↑ Zafarul Islam: Qazi Athar Mubarakpuri’s Studies on Jats, The Jats, Vol. II, Ed. Dr Vir Dingh, Delhi, 2006. p. 27

- ↑ Ibn Khurdazbeh , op.cit , p. 43

- ↑ Al-Istakhari, op, cit. , p. 94

- ↑ Zafarul Islam: Qazi Athar Mubarakpuri’s Studies on Jats, The Jats, Vol. II, Ed. Dr Vir Dingh, Delhi, 2006. p. 27

- ↑ Al Baladhrui, Futuh al-Buldan, al Matba al-Misriah, Cairo , 1932 pp. 166,367,369

- ↑ Qazi Athar, P.66

- ↑ Al Tabari, Tarikh-i-Tabari. Barul Maarif, Cairo 1962, III/304

- ↑ Qazi Athar, pp, 66-67

- ↑ Zafarul Islam: Qazi Athar Mubarakpuri’s Studies on Jats, The Jats, Vol. II, Ed. Dr Vir Dingh, Delhi, 2006. p. 27

- ↑ Ibn Hisha, Sirat al-Nabi, Darul Fikr, Cairo (n.d.) iv/264

- ↑ Zafarul Islam: Qazi Athar Mubarakpuri’s Studies on Jats, The Jats, Vol. II, Ed. Dr Vir Singh, Delhi, 2006. p. 28

- ↑ Zafarul Islam: Qazi Athar Mubarakpuri’s Studies on Jats, The Jats, Vol. II, Ed. Dr Vir Singh, Delhi, 2006. p. 28

- ↑ Qazi Athar , pp. 67-68

- ↑ Zafarul Islam: Qazi Athar Mubarakpuri’s Studies on Jats, The Jats, Vol. II, Ed. Dr Vir Singh, Delhi, 2006. p. 28

- ↑ Lisan al-Arab, VII/308 Majma Bihar al-Anwar, II/62

- ↑ Lisan al-Arab, VII/308

- ↑ Qazi Athar, P. 68

- ↑ Al-Jahiz Kitab-al-Haiwan, Mustafa al-Babi-al-Balbi, Egypt, 1943, V/ 407

- ↑ Majam-al-Bahria, under Zutt (as cited by Qazi Athar, P. 69.)

- ↑ Zafarul Islam: Qazi Athar Mubarakpuri’s Studies on Jats, The Jats, Vol. II, Ed. Dr Vir Dingh, Delhi, 2006. p. 28

- ↑ Quzi Athar, p. 69

- ↑ Zafarul Islam: Qazi Athar Mubarakpuri’s Studies on Jats, The Jats, Vol. II, Ed. Dr Vir Singh, Delhi, 2006. p. 29

- ↑ Qazi Athar, p. 68-70

- ↑ Zafarul Islam: Qazi Athar Mubarakpuri’s Studies on Jats, The Jats, Vol. II, Ed. Dr Vir Singh, Delhi, 2006. p. 29

Back to Jat people

Back to History