Porus

| Author:Laxman Burdak, IFS (R) |

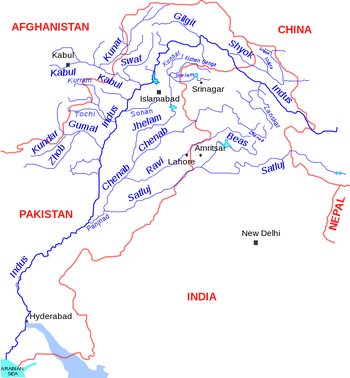

King Porus (पौरुष), the Greek version of the Indian names Puru, Pururava, or Parvata, was the ruler of a Kingdom in Punjab located between the Jhelum and the Chenab (in Greek, the Hydaspes and the Acesines) rivers in the Punjab. Its capital may have been near the current city of Lahore [1].

Variants

- Porus (Anabasis by Arrian, p. 280-306, 315, 318.)

- Pauravas had established a strong kingdom ruled over by their chief Paurusha or Paurava whom the Greeks called Poros.[2]

Jat Gotras Namesake

- Paraswal = Porus (Anabasis by Arrian, p. 280-306, 315, 318.)

- Phour = Porus (Anabasis by Arrian, p. 280-306, 315, 318.)

- Por = Porus (Anabasis by Arrian, p. 280-306, 315, 318.)

- Poras = Porus (Anabasis by Arrian, p. 280-306, 315, 318.)

- Porashwar = Porus (Anabasis by Arrian, p. 280-306, 315, 318.)

- Poraswal = Porus (Anabasis by Arrian, p. 280-306, 315, 318.)

- Poraswar = Porus (Anabasis by Arrian, p. 280-306, 315, 318.)

- Porosh = Porus (Anabasis by Arrian, p. 280-306, 315, 318.)

- Porous = Porus (Anabasis by Arrian, p. 280-306, 315, 318.)

- Porwal = Porus (Anabasis by Arrian, p. 280-306, 315, 318.)

- Purwar = Porus (Anabasis by Arrian, p. 280-306, 315, 318.)

History

Bhim Singh Dahiya[3] writes....Some authorities have given an opinion that the name Porus has not been derived from Paurava and cannot be equated with this ancient name. "The guess that Porus might be Paurava is not very convincing".138 "Porus (is) not to be identified with Paurava but with a derivative of Pura of Ganapatha of Panini.139 Thus it is clear that Porus cannot be identified with Paurava or any ancient Indian name. Jayaswal's suggestion that it is related to Pura of Ganapatha of Panini seems to be correct because even today this clan of the Jats is known as Poriya or Phor, the later being the form given by Muslim historians. It seems that Puriya and Phor/Por are one and the same clan, though existing today under both the forms, among the Jats.

138. V.Smith, EHI,p. 56

139. K.P.Jayaswal, Hindu Polity, p. 67, note.60

Ram Sarup Joon[4] writes....According to the Purans and Mahabharat, King Yayati chose his second son Puru as heir to the throne. This branch, therefore, continued to stay in the same area and ruled Hardwar, Hastinapur and Delhi. King Hasti made Hastinapur and Pandavas Indraprastha as their capital. Porus who fought Alexander belonged to this branch, Poruswal, Phalaswal,Mirhan, Mudgil, Gill and a number of other Jat gotras are of the Puru branch.

Ram Sarup Joon[5] writes that ....Alexander invaded India in 326 BC and came upto the River Beas. After crossing the River Indus at Attock, he had to fight with a series of Jat Kingdoms. Alexander's historian Arrian writes that Jats were the bravest people he had to contest with in India.

Alexander's first encounter was with Porus who was defeated. Alexander was impressed with his dignified behavior even after defeat and reinstated him on the throne.

According to Arrian, Alexander had to fight with two Porus-es, the other one on his return journey. This is because Porus was not a name but a title as both belonged to Puru dynasty.

Porus had 600 small republics under him, which were ruled by Jats. Porus was most powerful of them.[6]

Unlike his neighbour, Ambhi (in Greek: 'Omphius), the King of Taxila, Porus chose to fight Alexander the Greek invader in order to defend his kingdom and honour of the people.

Porus fought the battle of the Hydaspes River with Alexander in 326 BC. After he was defeated by Alexander, in a famous meeting with Porus - who had suffered many arrow wounds in the battle and had lost his sons, who all chose death in battle rather than surrender - Alexander reportedly asked him, "how he should treat him". Porus replied, "the way one king treats another". Alexander the Great was so impressed by the brave response of King Porus that he restored his captured Kingdom back to him and gave addition lands of a neighbouring area whose ruler had fled[7]

Porus was said to be "5 cubits tall", either the implausible 7½ ft (2.3 m) assuming an 18-inch cubit, or the more likely 6 ft (1.8 m) if a 14-inch Macedonian cubit was meant.

Buddha Prakash[8] mentions ....To the east of the Jhelum the Pauravas had established a strong kingdom ruled over by their chief Paurusha or Paurava whom the Greeks called Poros. Whereas the territory between the Jhelum and the Chenab was under his direct rule, that between the Chenab and the Ravi was placed under his nephew. The strength and power of this state can be measured by the vast army which Poros had organized and the discipline and solidarity with which it conducted itself on the field of battle.

Death of Poros

Buddha Prakash[9] mentions ....[p.91]: After the occupation of Pataliputra and the eradication of Nanda rule, Kautilya encompassed the murder of Poros through the Greek general Eudamus who is probably Dingarāta of the Mudraraksasa who, as this drama suggests, did it through a poison-girl.

On the death of Poros, Candragupta was the undisputed master of the empire of northern India. Poros' son Malayaketu broke away from Candragupta and joined the minister of the former Nanda king, but Kautilya won over that minister leaving him in the lurch. Eventually Malayaketu was captured and presented before Candragupta, but, through the intercession of Kautilya, his ancestral kingdom in the Panjab was restored to him and he returned there with his associates. He also patched up his affairs with Eudamus and, at his instance, went to Iran to assist Eumenes against Antigonus in the battle of Gabiene in 316 B. C. But in that battle he died and his kingdom was annexed to the Maurya empire (Buddha Prakash, Studies in Indian History and Civilization, pp. V I38-141).

[p.92]: It is clear from the above account that the Maurya empire was the creation of the Panjabis. It was they who laid its foundations in the Panjab under the leadership of Poros, Candragupta and Kautilya and then spread it up to Magadha. After that they took a prominent part in its conservation and proved its ardent defenders. This was demonstrated on the occasion of the invasion of Seleucos in 305 B. C.

Ch. 8: March of Alexander from the Indus to the Hydaspes (Jhelum) 326 BC (p.279-280)

Arrian[10] writes....THIS has been the method of constructing bridges, practised by the Romans from olden times; but how Alexander laid a bridge over the river Indus I cannot say, because those who served in his army have said nothing about it. But I should think that the bridge was made as near as possible as I have described, or if it were effected by some other contrivance so let it be. When Alexander had crossed to the other side of the river Indus, he again offered sacrifice there, according to his custom1. Then starting from the Indus, he arrived at Taxila, a large and prosperous city, in fact the largest of those situated between the rivers Indus and Hydaspes. He was received in a friendly manner by Taxiles, the governor of the city, and by the Indians of that place; and he added to their territory as much of the adjacent Country as they asked for. Thither also came to him envoys from Abisares, king of the mountaineer Indians, the embassy including the brother of Abisares as well as the other most notable men. Other envoys also came from Doxareus, the chief of the province, bringing gifts with them. Here again at Taxila Alexander offered the sacrifices which were customary for him to offer, and celebrated a gymnastic and equestrian contest. Having appointed Philip, son of Machatas, viceroy of the Indians of that district, he left a garrison in Taxila, as well as the soldiers who were invalided by sickness, and then marched towards the river Hydaspes.

For he was informed that Porus2, with the whole of his army, was on the other side of that river, having determined either to prevent him from making the passage, or to attack him while crossing. When Alexander ascertained this, he sent Coenus, son of Polemocrates, back to the river Indus, with instructions to cut in pieces all the vessels which he had repared for the passage of that river, and to bring them to the river Hydaspes. Coenus cut the vessels in pieces and conveyed them thither, the smaller ones being cut into two parts, and the thirty-oared galleys into three. The sections were conveyed upon waggons, as far as the bank of the Hydaspes; and there the vessels were fixed together again, and seen as a fleet upon that river. Alexander took the forces which he had when lie arrived at Taxila, and the 5,000 Indians under the command of Taxiles and the chiefs of that district, and marched towards the same river.

1. The place where Alexander crossed the Indus was probably at its junction with the Cophen or Cabul river, near Attock. Before he crossed he gave his army a rest of thirty days, as we learn from Diodorus, xvii. 86. From the same passage we learn that a certain king named Aphrices with an army of 20,000 men and 15 elephants, was killed by his own men and his army joined Alexander.

2. The kingdom of Porus lay between the Hydaspes and Acesines, the district now called Bari-doab with Lahore as capital. It was conquered by Lords Hardinge and Gongh in 1849.

Ch.9: Porus obstructs Alexander’s passage. (p.280-281)

ALEXANDER encamped on the bank of the Hydaspes, and Porus was seen with all his army and his large troop of elephants lining the opposite bank1. He remained to guard the passage at the place where he saw Alexander had encamped and sent guards to all the other parts of the river which were more easily fordable, placing officers over each detachment, being resolved to obstruct the passage of the Macedonians. When Alexander saw this, he thought it advisable to move his army in various directions, to distract the attention of Porus, and render him uncertain what to do. Dividing his army into many parts, he himself led some of his troops now into one part of the land and now into another, at one time ravaging the enemy’s property, at another looking out for a place where the river might appear easier for him to ford it. The rest of his troops he entrusted2 to his different generals, and sent them about in many directions. He also conveyed corn from all quarters into his camp from the land on this side the Hydaspes, so that it might be evident to Porus that he had resolved to remain quiet near the bank until the water of the river subsided in the winter, and afforded him a passage in many places. As his vessels were sailing up and down the river, and skins were being filled with hay, and the whole bank appeared to be covered in one place with cavalry and in another with infantry, Porus was not allowed to keep at rest or to bring his preparations together from all sides to any one point if he selected this as suitable for the defence of the passage. Besides at this season all the Indian rivers were flowing with swollen and turbid waters and with rapid currents; for it was the time of year when the sun is wont to turn towards the summer solstice3. At this season incessant and heavy rain falls in India; and the snows on the Caucasus, whence most of the rivers have their sources, melt and swell their streams to a great degree. But in the winter they again subside, become small and clear, and are fordable in certain places, with the exception of the Indus, Ganges, and perhaps one or two others. At any rate the Hydaspes becomes fordable.

1. Diodorus (xvii. 87) says that Porus had more than 50,000 infantry, about 3,000 cavalry, more than 1,000 chariots, and 130 elephants. Curtius (viii. 44) says he had about 30,000 infantry, BOO chariots, and 85 elephants.

2. επιστεψας is Krüger's reading instead of επιτάξας

3. About the month of May. See chap. 12 infra; also Curtius, viii. 45, 46. Strabo (xv. 1) quotes from Aristobulus describing the rainy season at the time of Alexander's battle with Porus at the Hydaspes.

Ch.10: Alexander and Porus at the Hydaspes. (p.282-283)

ALEXANDER therefore spread a report that he would wait for that season of the year, if his passage was obstructed at the present time ; but yet all the tune he was waiting in ambush to see whether by rapidity of movement he could steal a passage anywhere without being observed. But he perceived that it was impossible for him to cross at the place where Porus himself had encamped near the bank of the Hydaspes, not only on account of the multitude of his elephants, but also because a large army, and that, too, arranged in order of battle and splendidly accoutred, was ready to attack his men as they emerged from the water. Moreover he thought that his horses would refuse even to mount the opposite bank, because the elephants would at once fall upon them and frighten them both by their aspect and trumpeting; nor even before that would they remain upon the inflated hides during the passage of the river; but when they looked across and saw the elephants on the other side they would become frantic and leap into the water. He therefore resolved to steal a crossing by the following manoeuvre —In the night he led most of his cavalry along the bank in various directions, making a clamour and raising the battle-cry in honour of Enyalius.1 Every kind of noise was raised, as if they were making all the preparations necessary for crossing the river. Porus also marched along the river at the head of his elephants opposite the places where the clamour was heard, and Alexander thus gradually got him into the habit of leading his men along opposite the noise. But when this occurred frequently, and there was merely a clamour and a raising of the battle cry, Porus no longer continued to move about to meet the expected advance of the cavalry; but perceiving that his fear had been groundless2, he kept his position in the camp. However he posted his scouts at many places along the bank. When Alexander had brought it about that the mind of Porus no longer entertained any fear of his nocturnal attempts, he devised the following stratagem.

1. Cf. Arrian, i. 14 supra.

2. αλλα κενόν is Krüger's reading, instead of αλλ' εκεινον.

Ch.11: Alexander's Stratagem to get across (p.283-284)

THERE was in the bank of the Hydaspes, a projecting point, where the river makes a remarkable bend. It was densely covered by a grove1 of all sorts of trees; and over against it in the river was a woody island without a foot-track, on account of its being uninhabited. Perceiving that this island was right in front of the projecting point, and that both the spots were woody and adapted to conceal his attempt to cross the river, he resolved to convey his army over at this place. The projecting point and island were 150 stades distant from his great camp2. Along the whole of the bank, he posted sentries, separated as far as was consistent with keeping each other in sight, and easily hearing when any order should be sent along from any quarter. From all sides also during many nights clamours were raised and fires were burnt. But when he had made up his mind to undertake the passage of the river, he openly prepared his measures for crossing opposite the camp. Cratetus had been left behind at the camp with his own division of cavalry, and the horsemen from the Arachotians and Parapamisadians, as well as the brigades of Alcetas and Polysperchon from the phalanx of the Macedonian infantry, together with the chiefs of the Indians dwelling this side of the Hyphasis, who had with them 5,000 men. He gave Craterus orders not to cross the river before Porus moved off with his forces against them, or before he ascertained that Porus was in flight and that they were victorious.3 “If however,” said he, “Porus should take only a part of his army and march against me, and leave the other part with the elephants in his camp, in that case do thou also remain in thy present position. But if he leads all his elephants with him against me, and a part of the rest of his army is left behind in the camp, then do thou cross the river with all speed. For it is the elephants alone,” said he, “which render it impossible for the horses to land on the other bank. The rest of the army can easily cross.”

1. αλσει is Abicht's reading for ειδει.

2. About 17 miles.

3. This use of πρίν with infinitive after negative clauses, is contrary to Attic usage

Ch.12: Passage of the Hydaspes (p.284-285)

Such were the injunctions laid upon Craterus. Between the island and the great camp where Alexander had left this general, he posted Meleager, Attalus, and Gorgias, with the Grecian mercenaries, cavalry and infantry, giving them instructions to cross in detachments, breaking up the army as soon as they saw the Indians already involved in battle. He then picked the select body-guard called the Companions, as well as the cavalry regiments of Hephaestion, Perdiccas, and Demetrius, the cavalry from Bactria, Sogdiana, and Scythia, and the Daan horse-archers; and from the phalanx of infantry the shield-bearing guards, the brigades of Clitus and Coenus, with the archers and Agrianians, and made a secret march, keeping far away from the bank of the river, in order not to be seen marching towards the island and headland, from which he had determined to cross. There the skins were filled in the night with the hay which had been procured long before, and they were tightly stitched up. In the night a furious storm of rain occurred, on account of which his preparations and attempt to cross were still less observed, since the claps of thunder and the storm drowned with their din the clatter of the weapons and the noise which arose from the orders given by the officers. Most of the vessels, the thirty-oared galleys included with the rest, had been cut in pieces by his order and conveyed to this place, where they had been secretly fixed together again1 and hidden in the wood. At the approach of daylight, both the wind and the rain calmed down; and the rest of the army went over opposite the island, the cavalry mounting upon the skins, and as many of the foot soldiers as the boats would receive getting into them. They went so secretly that they were not observed by the sentinels posted by Porus, before they had already got beyond the island and were only a little way from the other bank.

1. The perf. pass. πέπηγμαι is used by Arrian and Dionysius, but by Homer and the Attic writers the form used is πέπηγα. Doric, πέπαγα.

Ch.13: Passage of the Hydaspes (p.285-287)

ALEXANDER himself embarked in a thirty-oared galley and went over, accompanied by Ptolemy, Perdiccas, and Lysimacbus, the confidential body-guards, Seleucus, one of the Companions, who was afterwards king1, and half of the shield-bearing guards; the rest of these troops being conveyed in other galleys of the same size. When the soldiers got beyond the island, they openly directed their course to the bank; and when the sentinels perceived that they had started, they at once rode off to Porus as fast as each man’s horse could gallop. Alexander himself was the first to land, and he at once took the cavalry as they kept on landing from his own and the other thirty-oared galleys, and drew them up in proper order. For the cavalry had been arranged to land first; and at the head of these in regular array he advanced. But through ignorance of the locality he had effected a landing on ground which was not a part of the mainland, but an island, a large one indeed and where from the fact that it was an island, he more easily escaped notice. It was cut off from the rest of the land by a part of the river where the water was shallow. However, the furious storm of rain, which lasted the greater part of the night, had swelled the water so much that his cavalry could not find out the ford; and he was afraid that he would have to undergo another labour in crossing as great as the first. But when at last the ford was found, he led his men through it with much difficulty; for where the water was deepest, it reached higher than the breasts of the infantry; and of the horses only the heads rose above the river2. When he had also crossed this piece of water, he selected the choice guard of cavalry, and the best men from the other cavalry regiments, and brought them up from column into line on the right wing3. In front of all the cavalry he posted the horse-archers, and placed next to the cavalry in front of the other infantry the royal shield-bearing guards under the command of Seleucus. Near these he placed the royal foot-guard, an d next to these the other shield-bearing guards, as each happened at the time to have the right of precedence. On each side, at the extremities of the phalanx, his archers, Agrianians and javelin-throwers were posted.

1. Seleucus Nicator, the most powerful of Alexander's successors, became king of Syria and founder of the dynasty of the Σeleucidae, which came to an end in B.C. 79.

2. For this use of όσον, cf. Homer (Iliad, ix. 354); Herodotus, iv. 45; Plato (Gorgias, 485A; Euthydemus, 273A).

3. Compare the passage of the Rhone by Hannibal., (See Livy, xxi. 26-28; Polybius, iii. 45, 46.)

Ch.14: The battle at the Hydaspes (p.287-288)

Arrian[11] writes.... HAVING thus arranged his army, he ordered the infantry to follow at a slow pace and in regular order, numbering as it did not much under 6,000 men ; and because he thought he was superior in cavalry, he took only his horse-soldiers, who were 5,000 in number, and led them forward with speed. He also instructed Tauron, the commander of the archers, to lead them on also with speed to back up the cavalry. He had come to the conclusion that if Porus should engage him with all his forces, he would easily be able to overcome him by attacking with his cavalry, or to stand on the defensive until his infantry arrived in the course of the action; but if the Indians should be alarmed at his extraordinary audacity in making the passage of the river and take to flight, he would be able to keep close to them in their flight, so that the slaughter of them in the retreat being greater, there would be only a slight work left for him. Aristobulus says that the son of Porus arrived with about sixty chariots before Alexander made his later passage from the large island, and that he could have hindered Alexander’s crossing (for he made the passage with difficulty even when no one opposed him), if the Indians had leaped clown from their chariots and assaulted those who first emerged from the water. But he passed by with the chariots and thus made the passage quite safe for Alexander; who on reaching the bank discharged his horse-archers against the Indians in the chariots, and these were easily put to rout, many of them being wounded. Other writers say that a battle took place between the Indians, who came with the son of Porus, and Alexander at the head of his cavalry when the passage had been effected, that the son of Porus came with a greater force, that Alexander himself was wounded by him, and that his horse Bucephalas, of which he was exceedingly fond, was killed, being wounded like his master by the son of Porus. But Ptolemy, son of Lagos, with whom I agree, gives a different account. This author also says that Porus dispatched his son, but not at the head of merely sixty chariots; nor is it indeed likely that Porus hearing from his scouts that either Alexander himself or at any rate a part of his army had effected the passage of the Hydaspes, would dispatch his son against him with only sixty chariots.’ These indeed were too many to be sent out as a reconnoitring party, and not adapted for speedy retreat; but they were by no means a sufficient force to keep back those of the enemy who had not yet got across, as well as to attack those who had already landed. Ptolemy says that the son of Porus arrived at the head of 2,000 cavalry and 120 chariots; but that Alexander had already made even the last passage from the island before he appeared.

Ch.15: Arrangements of Porus (p.288-290)

Arrian[12] writes....Ptolemy also says that Alexander in the first place sent the horse-archers against these, and led the cavalry himself, thinking that Porus was approaching with all his forces, and that this body of cavalry was marching in front of the rest of his army, being drawn up by him as the vanguard. But as soon as he had ascertained with accuracy the number of the Indians, he immediately made a rapid charge upon them with the cavalry around him. When they perceived that Alexander himself and the body of cavalry around him had made the assault, not in line of battle regularly formed, but by squadrons, they gave way; and 400 of their cavalry, including the son of Porus, fell in the contest. The chariots also were captured, horses and all, being heavy and slow in the retreat, and useless in the action itself on account of the clayey ground. When the horsemen who had escaped from this rout brought news to Porus that Alexander himself had crossed the river with the strongest part of his army, and that his son had been slain in the battle, he nevertheless could not make up his mind what course to take, because the men who had been left behind under Craterus were seen to be attempting to cross the river from the great camp which was directly opposite his position. However, at last he preferred to march against Alexander himself with all his army, and to come into a decisive conflict with the strongest division of the Macedonians, commanded by the king in person. But nevertheless he left a few of the elephants together with a small army there at the camp to frighten the cavalry under Craterus from the bank of the river. He then took all his cavalry to the number of 4,000 men, all his chariots to the number of 300, with 200 of his elephants and all the infantry available to the number of 30,000,’ and marched against Alexander. When he found a place where he saw there was no clay, but that on account of the sand the ground was all level and hard, and thus fit for the advance and retreat of horses, he there drew up his army.2 First he placed the elephants in the front, each animal being not less than a plethrum1 apart, so that they might be extended in the front before the whole of the phalanx of infantry, and produce terror everywhere among Alexander’s cavalry. Besides he thought that none of the enemy would have the audacity to push themselves into the spaces between the elephants, the cavalry being deterred by the fright of their horses; and still less would the infantry do so, it being likely they would be kept off in front by the heavy-armed soldiers falling upon them, and trampled down by the elephants wheeling round against them. Near these he had posted the infantry, not occupying a line on a level with the beasts, but in a second line behind them, only so far behind that the companies of foot might be thrown forward a short distance into the spaces between them. He had also bodies of infantry standing beyond the elephants on the wings; and on both sides of the infantry he had posted the cavalry, in front of which were placed the chariots on both wings of his army.

1. 100 Greek and 101 English feet.

Ch.16: Alexander's tactics. (p.p.290-291)

Arrian[13] writes.... Such was the arrangement which Porus made of his forces. As soon as Alexander observed that the Indians were drawn up in order of battle, he stopped his cavalry from advancing farther, so that he might take up the infantry as it kept on arriving; and even when the phalanx in quick march had effected a junction with the cavalry, he did not at once draw it out and lead it to the attack, not wishing to hand over his men exhausted with fatigue and out of breath, to the barbarians who were fresh and untired. On the contrary, he caused his infantry to rest until their strength was recruited, riding along round the lines to inspect them1. When he had surveyed the arrangement of the Indians, he resolved not to advance against the centre, in front of which the elephants had been posted, and in the gaps between them a dense phalanx of men arranged; for he was alarmed at the very arrangements which Porus had made here with that express design. But as he was superior in the number of his cavalry, he took the greater part of that force, and marched along against the left wing of the enemy for the purpose of making an attack in this direction. Against the right wing he sent Coenus with his own regiment of cavalry and that of Demetrius, with instructions to keep close behind the barbarians when they, seeing the dense mass of cavalry opposed to them, should ride out to fight them. Seleucus, Antigenes, and Tauron were ordered to lead the phalanx of infantry, but not to engage in the action until they observed2 the enemy’s cavalry and phalanx of infantry thrown into disorder by the cavalry under his own command. But when they came within range of missiles, he launched the horse-archers, 1,000 in number, against the left wing of the Indians, in order to throw those of the enemy who were posted there into confusion by the incessant storm of arrows and by the charge of the horses. He himself with the Companion cavalry marched along rapidly against the left wing of the barbarians, being eager to attack them in ftank while still in a state of disorder, before their cavalry could he deployed in line.

1. See Donaldson's New Gratylus, sec. 178.

2. πριν κατιδωσιν. In Attic, πριν αν is the regular form with the subjunctive; but in Homer and the Tragic writers αν is often omitted.

Ch.17: Defeat of Porus (p.291-293)

Arrian[14] writes.... Meantime the Indians had collected their cavalry from all parts, and were riding along, advancing out of their position to meet Alexander’s charge. Coenus also appeared with his men in their rear, according to his instructions. The Indians, observing this, were compelled to make the line of their cavalry face both ways;1 the largest and best part against Alexander, while the rest wheeled round against Coenus and his forces. This therefore at once threw the ranks as well as the decisions of the Indians into confusion. Alexander, seeing his opportunity, at the very moment the cavalry was wheeling round in the other direction, made an attack on those opposed to him with such vigour that the Indians could not sustain the charge of his cavalry, but were scattered and driven to the elephants, as to a friendly wall, for refuge. Upon this, the drivers of the elephants urged forward the beasts against the cavalry but now the phalanx itself of the Macedonians was advancing against the elephants, the men casting darts at the riders and also striking the beasts themselves, standing round them on all sides. The action was unlike any of the previous contests; for wherever the beasts could wheel round, they rushed forth against the ranks of infantry and demolished the phalanx of the Macedonians, dense as it was. The Indian cavalry also, seeing that the infantry were engaged in the action, rallied again and advanced against the Macedonian cavalry. But when Alexander’s men, who far excelled both in strength and military discipline, got the mastery over them the second time, they were again repulsed towards the elephants and cooped up among them. By this time the whole of Alexander’s cavalry had collected into one squadron, not by any command of his, but having settled into this arrangement by the mere effect of the struggle itself; and wherever it fell upon the ranks of the Indians they were broken lip with great slaughter. The beasts being now cooped up into a narrow space, their friends were no less injured by them than their foes, being trampled down in their wheeling and pushing about. Accordingly there ensued a great slaughter of the cavalry, cooped tip as it was in a narrow space around the elephants. Most of the keepers of the elephants had been killed by the javelins, and some of the elephants themselves had been wounded, while others no longer kept apart in the battle on account of their sufferings or from being destitute of keepers. But, as if frantic with pain, rushing forward at friends and foes alike, they pushed about, trampled down and killed them in every kind of way. However, the Macedonians inasmuch as they were attacking the beasts in an open space and in accordance with their own plan, got out of their way whenever they rushed at them; and when they wheeled round to return, followed them closely and hurled javelins at them; whereas the Indians retreating among them were now receiving greater injury from them. But when the beasts were tired out, and were no longer able to charge with any vigour, they began to retire slowly, facing the foe like ships backing water,’ merely uttering a shrill piping sound. Alexander himself surrounded the whole line with his cavalry, and gave the signal that the infantry should link their shields together so as to form a very densely closed body, and thus advance in phalanx. By this means the Indian cavalry, with the exception of a few men, was quite cut up in the action; as was also the infantry, since the Macedonians were now pressing upon them from all sides. Upon this, all who could do so turned to flight through the spaces which intervened between the parts of Alexander’s cavalry.

1. Cf. Arrian's Tactics, chap. 29.

Ch.18: Losses of the combatants.— Porus surrenders. (p.293-295)

Arrian[15] writes.... At the same time Craterus and the other officers of Alexander’s army who had been left behind on the bank of the Hydaspes crossed the river, when they perceived that Alexander was winning a brilliant victory. These men, being fresh, followed up the pursuit instead of Alexander’s exhausted troops, and made no less a slaughter of the Indians in their retreat. Of the Indians little short of 20,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry were killed in this battle.1 All their chariots were broken to pieces; and two sons of Porus were slain, as were also Spitaces, the governor of the Indians of that district, the managers of the elephants and of the chariots, and all the cavalry officers and generals of Porus’s army. All the elephants which were not killed there, were captured. Of Alexander’s forces, about 80 of the 6,000 foot-soldiers who were engaged in the first attack were killed,; 10 of the horse-archers, who were also the first to engage in the action; about 20 of the Companion cavalry, and about 200 of the other horsemen fell2. When Porus, who exhibited great talent in the battle, performing the deeds not only of a general but also of a valiant soldier, observed the slaughter of his cavalry, and some of his elephants lying dead, others destitute of keepers straying about in a forlorn condition, while most of his infantry had perished, he did not depart as Darius the Great King did, setting an example of flight to his men; but as long as any body of Indians remained compact in the battle, he kept up the struggle. But at last, having received a wound on the right shoulder, which part of his body alone was unprotected during the battle, he wheeled round. His coat of mail warded off the missiles from the rest of his body, being extraordinary both for its strength and the close fitting of its joints, as it was afterwards possible for those who saw him to observe. Then indeed he turned his elephant round and began to retire. Alexander, having seen that he was a great man and valiant in the battle, was very desirous of saving his life. He accordingly sent first to him Taxiles the Indian ; who rode up as near to the elephant which was carrying Porus as seemed to him safe, and bade him stop the beast, assuring him that it was no longer possible for him to flee, and bidding him listen to Alexander’s message. But when he saw his old foe Taxiles, he wheeled round and was preparing to strike him with a javelin; and perhaps he would have killed him, if he had not quickly driven his horse forward out of the reach of Porus before he could strike him. But not even on this account was Alexander angry with Porus; but he kept on sending others in succession; and last of all Meroës an Indian, because he ascertained that he was an old friend of Porus. As soon as the latter heard the message brought to him by Meroës, being at the same time overcome by thirst, he stopped his elephant and dismounted from it. After he had drunk some water and felt refreshed, he ordered Meroës to lead him without delay to Alexander; and Meroës led him thither.3

1. Diodorus (xvii. 89) says that more than 12,000 Indians were killed in this battle, over 9,000 being captured, besides 80 elephants.

2. According to Diodorus there fell of the Macedonians 280 cavalry and more than 700 infantry. Plutarch (Alex. 60) says that the battle lasted eight hours.

3. Curtius (viii. 50, 51) represents Porus sinking half dead, and being protected to the last by his faithful elephant. Diodorus (xvii. 88) agrees with him

Ch.19: Alliance with Porus.— death of Bucephalas (p.295-297)

Arrian[16] writes.... When Alexander heard that Meroës was bringing Porus to him, he rode in front of the line with a few of the Companions to meet Porus; and stopping his horse, he admired his handsome figure and his stature,[1] which reached somewhat above five cubits. He was also surprised that he did not seem to be cowed in spirit,[2] but advanced to meet him as one brave man would meet another brave man, after having gallantly struggled in defence of his own kingdom against another king. Then indeed Alexander was the first to speak, bidding him say what treatment he would like to receive. The report goes that Porus replied: "Treat me, Alexander, in a kingly way!" Alexander being pleased at the expression, said: "For my own sake, Porus, thou shalt be thus treated; but for thy own sake do thou demand what is pleasing to thee!" But Porus said that everything was included in that, Alexander, being still more pleased at this remark, not only granted him the rule over his own Indians, but also added another country to that which he had before, of larger extent than the former.[3] Thus he treated the brave man in a kingly way, and from that time found him faithful in all things. Such was the result of Alexander's battle with Porus and the Indians living beyond the river Hydaspes, which was fought in the archonship of Hegemon at Athens, in the month Munychion[4] (18 April to 18 May, 326 B.C.).

Alexander founded two cities, one where the battle took place, and the other on the spot whence he started to cross the river Hydaspes; the former he named Nicaea,[5] after his victory over the Indians, and the latter Bucephala in memory of his horse Bucephalas, which died there, not from having been wounded by any one, but from the effects of toil and old age; for he was about thirty years old, and quite worn out with toil.[6] This Bucephalas had shared many hardships and incurred many dangers with Alexander during many years, being ridden by none but the king, because he rejected all other riders. He was both of unusual size and generous in mettle. The head of an ox had been engraved upon him as a distinguishing mark, and according to some this was the reason why he bore that name; but others say, that though he was black he had a white mark upon his head which bore a great resemblance to the head of an ox. In the land of the Uxians this horse vanished from Alexander, who thereupon sent a proclamation throughout the country that he would kill all the inhabitants, unless they brought the horse back to him. As a result of this proclamation it was immediately brought back. So great was Alexander's attachment to the horse, and so great was the fear of Alexander entertained by the barbarians.[7] Let so much honour be paid by me to this Bucephalas for the sake of his master.

1. Cf. Curtius, viii. 44; Justin, xii. 8.

2. Cf. Arrian, ii. 10 supra. δεουλωμένος τη γνωμη. The Scholiast on Thucydides iv. 34, explains this by τεταπεινωμένος φοβω.

3. Cf. Plutarch (Alex., 60); Curtius, viii. 51.

4. Diodorus (xvii. 87) says that the battle was fought in the archonship of Chremes at Athens.

5. Nicaea is supposed to be Mong and Bucephala may be Jelalpur. See Strabo, xv. 1.

6. Cf. Plutarch (Alex., 61). Schmieder says that Alexander could not have broken in the horse before he was sixteen years old. But since at this time he was in his twenty-ninth year he would have had him thirteen years. Consequently the horse must have been at least seventeen years old when he acquired him. Can any one believe this? Yet Plutarch also states that the horse was thirty years old at his death.

7. Curtius (vl. 17) says this occurred in the land of the Mardians; whereas Plutarch (Alex., 44) says it happened in Hyrcania.

Ch.20: Conquest of the Glausians.— Embassy from Abisares. —Passage of the Acesines (Chenab) (p.297-299)

WHEN Alexander had paid all due honours to those who had been killed in the battle, he offered the customary sacrifices to the gods in gratitude for his victory, and celebrated a gymnastic and horse contest upon the bank of the Hydaspes at the place where he first crossed with his army1. He then left Craterus behind with a part of the army, to erect and fortify the cities which he was founding there; but he himself marched against the Indians conterminous with the dominion of Porus. According to Aristobulus the name of this nation was Glauganicians; but Ptolemy calls them Glausians. I am quite indifferent which name it bore. Alexander traversed their land with half the Companion cavalry, the picked men from each phalanx of the infantry, all the horse-bowmen, the Agrianians, and the archers. All the inhabitants came over to him on terms of capitulation; and he thus took thirty-seven cities, the inhabitants of which, where they were fewest, amounted to no less then 5,000, and those of many numbered above 10000. He also took many villages, which were no less populous than the cities. This land also he granted to Porus to rule; and sent Taxiles back to his own abode after effecting a reconciliation between him and Porus. At this time arrived envoys from Abisares,2 who told him that their king was ready to surrender himself and the land which he ruled. And yet before the battle which was fought between Alexander and Porus, Abisares intended to join his forces with those of the latter. On this occasion he sent his brother with the other envoys to Alexander, taking with them money and forty elephants as a gift. Envoys also arrived from the independent Indians, and from a certain other Indian ruler named Porus.3 Alexander ordered Abisares to come to him as soon as possible, threatening that unless he came he would see him arrive with his army at a place where he would not rejoice to see him. At this time Phrataphernes, viceroy of Parthia and Hyrcania, came to Alexander at the head of the Thracians who had been left with him. Messengers also came from Sisicottus, viceroy of the Assacenians, to inform him that those people had slain their governor and revolted from Alexander. Against these he dispatched Philip and Tyriaspes with an army, to arrange and set in order the affairs of their land. He himself advanced towards the river Acesines.4 Ptolemy, son of Lagus, has described the size of this river alone of those in India, stating that where Alexander crossed it with his army upon boats and skins, the stream was rapid and the channel was full of large and sharp rocks, over which the water being violently carried seethed and dashed. He says also that its breadth amounted to fifteen stades; that those who went over upon skins had an easy passage but that not a few of those who crossed in the boats perished there in the water, many of the boats being wrecked upon the rocks and dashed to pieces. From this description theft it would be possible for one to come to a conclusion by comparison, that the size of the river Indus has been stated not far from the fact by those who think that its mean breadth is forty stades, but that it contracts to fifteen stades where it is narrowest and therefore deepest; and that this is the width of the Indus in many places. I come then to the conclusion that Alexander chose a part of the Acesines where the passage was widest, so that he might find the stream slower than elsewhere.

1. Diodorus (xvii. 89), says Alexander made a halt of 30 days after this battle.

2. Cf. Arrian, v. 8 supra, where an earlier embassy from Abisares is mentioned.

3. Strabo (xv. 1) says that this Porus was a cousin of the Porus captured by Alexander.

4. This is the Chenab. See Arrian (Indica, iii.), who says that where it joins the Indus it is 30 stades broad.

Ch.21: Advance beyond the Hydraotes (Ravi) (p.299-301)

AFTER crossing the river1, he left Coenus with his own brigade there upon the bank, with instructions to superintend the passage of the part of the army which had been left behind for the purpose of collecting2 corn and other supplies from the country of the Indians which was already subject to him. He now sent Porus away to his own abode, commanding him to select the most warlike of the Indians and take all the elephants he had and come to him. He resolved to pursue the other Porus, the bad one, with the lightest troops in his army, because he was informed that he had left the land which he ruled and had fled. For this Porus, while hostilities subsisted between Alexander and the other Porus, sent envoys to Alexander offering to surrender both himself and the land subject to him, rather out of enmity to Porus than from friendship to Alexander. But when he ascertained that the former had been released, and that he was ruling over another large country in addition to his own, then, fearing not so much Alexander as the other Porus, his namesake, he fled from his own land, taking with him as many of his warriors as he could persuade to share his flight. Against this man Alexander marched, and arrived at the Hydraotes3, which is another Indian river, not less than the Acesines (Chenab) in breadth, but less in swiftness of current. He traversed the whole country as far as the Hydraotes, leaving garrisons in the most suitable places, in order that Craterus and Coenus might advance with safety, scouring most of the land for forage. Then he dispatched Hephaestion into the land of the Porus who had revolted, giving him a part of the army, comprising two brigades of infantry, his own regiment of cavalry with that of Demetrius and half of the archers, with instructions to hand the country over to the other Porus, to win over any independent tribes of Indians which dwelt near the banks of the river Hydraotes, and to give them also into the hands of Porus to rule. He himself then crossed the river Hydraotes, not with difficulty, as he had crossed the Acesines. As he was advancing into the country beyond the bank of Hydraotes, it happened that most of the people yielded themselves up on terms of capitulation; but some came to meet him with arms, while others who tried to escape he captured and forcibly reduced to obedience.

1. Diodorus (xvii. 95) says that Alexander received a reinforcement from Greece at this river of more than 30,000 infantry and nearly 6,000 cavalry; also suits of armour for 25,000 infantry, and 100 talents of medical drugs.

2. Μέλλειν is usually connected with the future infinitive; but Arrian frequently uses it with the present.

3. Now called the Ravi.

Ch.22: Invasion of the Land of the Cathaeans (p.301-302)

MEANTIME he received information that the tribe called Cathaeans and some other tribes of the independent Indians were preparing for battle, if he approached their land; and that they were summoning to the enterprise all the tribes conterminous with them who were in like manner independent. He was also informed that the city, Sangala by name1, near which they were thinking of having the struggle, was a strong one. The Cathaeans themselves were considered very daring and skillful in war; and two other tribes of Indians, the Oxydracians and Mallians, were in the same temper as the Cathaeans. For a short time before, it happened that Porus and Abisares had marched against them with their own forces and had roused many other tribes of the independent Indians to arms, but were forced to retreat without effecting anything worthy of the preparations they had made. When Alexander was informed of this, he made a forced march against the Cathaeans, and on the second day after starting from the river Hydraotes he arrived at a city called Pimprama, inhabited by a tribe of Indians named Adraistaeans, who yielded to him on terms of capitulation. Giving his army a rest the next day, he advanced on the third day to Sangala, where the Cathaeans and the other neighbouring tribes had assembled and marshalled themselves in front of the city upon a hill which was not precipitous on all sides. They had posted their waggons all round this hill and were encamping within them in such a way that they were surrounded by a triple palisade of waggons. When Alexander perceived the great number of the barbarians and the nature of their position, he drew up his forces in the order which seemed to him especially adapted to his present circumstances, and sent his horse-archers at once without any delay against them, ordering them to ride along and shoot at them from a distance; so that the Indians might not be able to make any sortie, before his army was in proper array, and that even before the battle commenced they might be wounded within their stronghold. Upon the right wing he posted the guard of cavalry and the cavalry regiment of Clitus; next to these the shield-bearing guards, and then the Agrianians. Towards the left he had stationed Perdiccas with his own regiment of cavalry, and the battalions of foot Companions. The archers he divided into two parts and placed them on each wing. While he was marshalling his army, the infantry and cavalry of the rear-guard came up. Of these, he divided the cavalry into two parts and led them to the wings, and with the infantry which came up he made the ranks of the phalanx more dense and compact. He then took the cavalry which had been drawn up on the right, and led it towards the waggons on the left wing of the Indians; for here their position seemed to him more easy to assail, and the waggons had not been placed together so densely.

1. Sangala is supposed to be Lahore; but probably it lay some distance from that city, on the bank of the Chenab.

Ch.23: Assault upon Sangala (p.302-304)

As the Indians did not run out from behind the waggons against the advancing cavalry, but mounted upon them and began to shoot from the top of them, Alexander, perceiving that it was not the work for cavalry, leaped down from his horse, and on foot led the phalanx of infantry against them. The Macedonians without difficulty forced the Indians from the first row of waggons; but then the Indians, taking their stand in front of the second row, more easily repulsed the attack, because they were posted in denser array in a smaller circle. Moreover the Macedonians were attacking them likewise in a confined space, while the Indians were secretly creeping under the front row of waggons, and without regard to discipline were assaulting their enemy through the gaps left between the waggons as each man found a chance1. But nevertheless even from these the Indians were forcibly driven by the phalanx of infantry. They no longer made a stand at the third row, but fled as fast as possible into the city and shut themselves up in it. During that day Alexander with his infantry encamped round the city, as much of it, at least, as his phalanx could surround for he could not with his camp completely encircle the wall, so extensive was it. Opposite the part uninclosed by his camp, near which also was a lake, he posted the cavalry, placing them all round the lake, which he discovered to be shallow. Moreover, he conjectured that the Indians, being terrified at their previous defeat, would abandon the city in the night; and it turned out just as he had conjectured; for about the second watch of the night most of them dropped down from the wall, but fell in with 2 the sentinels of cavalry.

The foremost of them were cut to pieces by these; but the men behind them perceiving that the lake was guarded all round, withdrew into the city again. Alexander now surrounded the city with a double stockade, except in the part where the lake shut it in, and round the lake he posted more perfect guards. He also resolved to bring military engines up to the wall, to batter it down. But some of the men in the city deserted to him, and told him that the Indians intended that very night to steal out of the city and escape by the lake, where the gap in the stockade existed. He accordingly stationed Ptolemy, son of Lagus, there, giving him three regiments of the shield-bearing guards, all the Agrianians, and one line of archers, pointing out to him the place where he especially conjectured the barbarians would try to force their way. “When thou perceivest the barbarians forcing their way here,” said he, “do thou, with the army obstruct their advance, and order the bugler to give the signal. And do you, 0 officers, as soon as the signal has been given, each being arrayed in battle order with your own men, advance towards the noise, wherever the bugle summons you. Nor will I myself withdraw from the action.”

1. Compare Csesar (Bell. Gall., i. 26): pro vallo carros objecerant et e loco superiore in nostros venientes tela conjiciebant, et nonnulli inter carros rotasque mataras ac tragulas subjiciebant nostrosque vulnerabant.

2. εγκυρειν is an epic and Ionic word rarely used in Attic; but found frequently in Herodotus, Homer, Hesiod, and Pindar.

Ch.24: Capture of Sangala (p.304-306)

SUCH were the orders he gave; and Ptolemy collected there as many waggons as he could from those which had been left behind in the first flight, and placed them athwart, so that there might seem to the fugitives in the night to be many difficulties in their way; and as the stockade had. been knocked down, or had not been firmly fixed in the ground, he ordered his men to heap up a mound of earth in various places between the lake and the wall. This his soldiers effected in the night. When it was about the fourth watch1, the barbarians, just as Alexander had been informed, opened the gates towards the lake, and made a run in that direction. However they did not escape the notice of the guards there, nor that of Ptolemy, who had been placed behind them to render aid. But at this moment the buglers gave the signal for him, and he advanced against the barbarians with his army fully equipped and drawn up in battle array. Moreover the waggons and the stockade which had been placed in the intervening space were an obstruction to them. When the bugle sounded and Ptolemy attacked them, killing the men as they kept on stealing out through the waggons, then indeed they turned back again into the city; and in their retreat 500 of them were killed. In the meanwhile Porus arrived, bringing with him the elephants that were left to him, and 5,000 Indians. Alexander had constructed his military engines and they were being led up to the wall; but before any of it was battered down, the Macedonians took the city by storm, digging under the wall, which was made of brick, and placing scaling ladders against it all round. In the capture a 7,000 of the Indians were killed, and above 70,000 were captured, besides 300 chariots and ~co cavalry. In the ~~‘hole siege a little less than 100 of Alexander’s army were killed; but the number of the wounded was greater than the proportion of the slain, being more than 1,200, among whom were Lysimacbus, the confidential body-guard, and other officers. After burying the dead according to his custom, Alexander sent Eurnenes, the secretary2, with 300 cavalry to the two cities which had joined Sangala in revolt, to tell those who held them about the capture of Sangala, and to inform them that they would receive no harsh treatment from Alexander if they stayed there and received him as a friend; for no harm had happened to any of the other independent Indians who had surrendered to him of their own accord. But they had become frightened, and had abandoned the cities and were fleeing; for the news had already reached them that Alexander had taken Sangala by storm. When Alexander was informed of their flight he pursued them with speed; but most of them were too quick for him, and effected their escape, because the pursuit began from a distant starting-place. But all those who were left behind in the retreat from weakness, were seized by the army and killed, to the number of about 5oo. Then, giving up the design of pursuing the fugitives any further, he returned to Sangala, and razed the city to the ground. He added the land to that of the Indians who had formerly been independent, but who had then voluntarily submitted to him. He then sent Porus with his forces to the cities which had submitted to him, to introduce garrisons into them ; whilst he himself with his army, advanced to the river Hyphasis3, to subjugate the Indians beyond it. Nor did there seem to him any end of the war, so long as anything hostile to him remained.

1. The Greeks had only three watches; but Arrian is speaking as a Roman.

2. Eumenes, of Cardia in Thrace, was private secretary to Philip and Alexander. After the death of the latter, he obtained the rule of Cappadocia, Paphlagonia, and Pontus. He displayed great ability both as a general and statesman; but was put to death by Antigonus in B.C. 316, when he was 45 years of age. Being a Greek, he was disliked by the Macedonian generals, from whom he experienced very unjust treatment. It is evident from the biographies of him written by Plutarch and Cornelius Nepos, that he was one of the most eminent men of his era.

3. Now called the Beas, or Bipasa. Strabo calls it Hypanis, and Pliny calls it Hypasis.

Ch.2: Voyage down the Hydaspes (p.318-319)

At this time Coenus, who was one of Alexander's most faithful Companions, fell ill and. died, and the king buried him with as much magnificence as circumstances allowed. Then collecting the Companions and the Indian envoys who had come to him, he appointed Porus king of the part of India which had already been conquered, seven nations in all, containing more than 2,000 cities. After this he made the following distribution of his army.[1] With himself he placed on board the ships all the shield-bearing guards, the archers, the Agrianians, and the body-guard of cavalry.[2] Craterus led a part of the infantry and cavalry along the right bank of the Hydaspes, while along the other bank Hephaestion advanced at the head of the most numerous and efficient part of the army, including the elephants, which now numbered about 200. These generals were ordered to march as quickly as possible to the place where the palace of Sopeithes was situated,[3] and Philip, the viceroy of the country beyond the Indus[4] extending to Bactria, was ordered to follow them with his forces after an interval of three days. He sent the Nysaean cavalry back to Nysa.[5] The whole of the naval force was under the command of Nearchus; but the pilot of Alexander's ship was Onesicritus, who, in the narrative which he composed of Alexander's campaigns, falsely asserted that he was admiral, while in reality he was only a pilot.[6] According to Ptolemy, son of Lagus, whose statements I chiefly follow, the entire number of the ships was about eighty thirty-oared galleys; but the whole number of vessels, including the horse transports and boats, and all the other river craft, both those previously plying on the rivers and those built at that time, fell not far short of 2,000.[7]

1. Plutarch (Alex. 66) informs ua that Alexander's army numbered 120,000 infantry and 15,000 cavalry. Cf. Arrian (Indica, 19).

2. Arrian, in the Indica (chap. 19), says that Alexander embarked with 8,000 men.

3. Strabo (xv. 1) says that the realm of Sopeithes was called Cathaia.

4. As Alexander was at this time east of the Indus, the expression, "beyond the Indus," means west of it.

5. Cf. Arrian, v. 2 supra.

6. Only fragments of this narrative are preserved. Strabo (xv. 1) says that the statements of Onesicritus are not to be relied upon.

7. Curtius (ix. 13) and Diodorus (xvii. 95) say that there were 1,000 vessels. Arrian (Indica, 19) says there were 800. Krüger reads χιλίων in this passage instead of the common reading δισχιλίων.

Alexander Cunningham on Porus

Alexander Cunningham[17] writes that - [p.155]:The modern town of Bhira, or Bheda, is situated on the left, or eastern bank, of the Jhelam ; but on the opposite bank of the river, near Ahmedabad, there is a very extensive mound of ruins, called Old Bhira, or Jobnathnagar, the city of Raja Jobnath, or Chobnath. At this point the two great routes of the salt caravans diverge to Lahor and Multan ; and here, accordingly, was the capital of the country in ancient times ; and here also, as I believe, was the capital of Sophites, or Sopeithes, the contemporary of Alexander the Great. According to Arrian, the capital of Sopeithes was fixed by Alexander as the point where the camps of Kraterus and Hephsestion were to be pitched on opposite banks of the river, there to await the arrival of the fleet of boats under his own command, and of the main body of the army under Philip.1 As Alexander reached the appointed place on the third day, we know that the capital of Sophites was on the Hydaspes, at three days' sail from Nikaea for laden boats. Now Bhira is just three days' boat distance from Mong, which, as I will presently show, was almost certainly the position of Nikaea, where Alexander defeated Porus. Bhira also, until it was supplanted by Pind Dadan Khan, has always been the principal city in this part of the country. At Bhira 2 the Chinese pilgrim, Fa-Hian, crossed the Jhelam in A.D. 400 ; and against Bhira, eleven centuries later, the enterprising Baber conducted his first Indian expedition.

The classical notices of the country over which

1 ' Anabasis,' vi. 3. 2 Beal's translation, chap. xv. ; Fa-Hian calls it Pi-cha or Bhi-ḍa — the Chinese ch being the usual representative of the cerebral ḍ.

[p.156]: Sophites ruled are very conflicting. Thus Strabo1 records : —

- " Some writers place Kathaea and the country of Sopeithes, one of the monarchs, in the tract between the rivers (Hydaspes and Akesines) ; some on the other side of the Akesines and of the Hyarotes, on the confines of the territory of the other Porus, — the nephew of Porus, who was taken prisoner by Alexander, and call the country subject to him Gandaris".

This name may, I believe, be identified with the present district of Gundalbar, or Gundar-bar. Bar is a term applied only to the central portion of each Doab, comprising the high lands beyond the reach of irrigation from the two including rivers. Thus Sandal, or Sandar-bar, is the name of the central tract of the Doab between the Jhelam and the Chenab. The upper portion of the Gundal Bar Doab, which now forms the district of Gujrat, belonged to the famous Porus, the antagonist of Alexander, and the upper part of the Sandar-Bar Doab belonged to his nephew, the other Porus, who is said to have sought refuge among the Gandaridae.

Death

Indian sources record that Parvata was killed by mistake by the Indian ruler Rakshasa, who was trying to assassinate Chandragupta instead.

Greek tradition however records that he was assassinated, sometime between 321 and 315 BC, by the Thracian general Eudemus (general), who had remained in charge of the Macedonian armies in the Punjab:

- "From India came Eudamus, with 500 horsemen, 300 footmen, and 120 elephants. These beasts he had secured after the death of Alexander, by treacherously slaying King Porus" Diodorus Siculus XIX-14

After his assassination, his son Malayketu ascended the throne with the help of Eudemus. However, Malayketu was killed in the Battle of Gabiene in 317 BC.

पुरु-पौरव का इतिहास

दलीप सिंह अहलावत[18] लिखते हैं कि सम्राट् ययाति के आज्ञाकारी उत्तराधिकारी लघुपुत्र पुरु से ही इस जाटवंश का प्रचलन हुआ। महाभारत आदिपर्व, अध्याय 85वां, श्लोक 35, के लेख अनुसार -

- पूरोस्तु पौरवो वंशो यत्र जातोसि पार्थिव ।

- इदं वर्षसहस्राणि राज्यं कारयितुं वशी ॥35॥

पुरु से पौरववंश चला है। इस चन्द्रवंशी पुरुवंश में बड़े-बड़े महान् शक्तिशाली सम्राट् हुए जैसे - वीरभद्र, दुष्यन्त, चक्रवर्ती भरत (सम्राट चक्रवर्ती भरत के नाम पर आर्यावर्त देश का नाम भारतवर्ष पड़ा), हस्ती (जिसने हस्तिनापुर नगर बसाया), कुरु (जिसने धर्मक्षेत्र कुरुक्षेत्र स्थापित किया), शान्तनु, भीष्म, कौरव पाण्डव आदि। इसी पुरुवंश की राजधानी हरद्वार, हस्तिनापुर, इन्द्रप्रस्थ तथा देहली रही।

जाट राजा पोरस

इसी पुरुवंश में 326 ईस्वी पूर्व जाट राजा पोरस अत्यधिक प्रसिद्ध सम्राट् हुआ। इनका राज्य जेहलम और चनाव नदियों के बीच के क्षेत्र पर था। “परन्तु इनके अधीन अन्य 600 राज्य थे तथा इन्होंने अपना राजदूत कई वर्ष ईस्वी पूर्व रोम (इटली) के राजा अगस्तटस (Augustus) के पास भेजा था।” (यूनानी प्रसिद्ध ऐतिहासिक स्ट्रेबो का यह लेख है। [19]। स्ट्रेबो का यह लेख ठीक ही प्रतीत होता है क्योंकि सम्राट् पोरस के समय भारत व आज के अरब देशों पर एक सम्राट् न था। परन्तु छोटे-छोटे क्षेत्रों पर अलग-अलग राजा राज करते थे। इनमें अधिकतर जाट राज्य थे, जिनका उचित स्थान पर वर्णन किया जायेगा। सम्राट् पोरस उन राजाओं से अधिक शक्तिशाली था।

- 1. आधार पुस्तक; जाटों का उत्कर्ष पृ० 297-299 लेखक योगेन्द्रपाल शास्त्री।

जाट वीरों का इतिहास: दलीप सिंह अहलावत, पृष्ठान्त-192

यूनानी शक्तिशाली सम्राट सिकन्दर ने 326 ई० पूर्व भारतवर्ष पर आक्रमण किया। सिकन्दर की सेना ने रात्रि में जेहलम नदी पार कर ली। जब पोरस को यह समाचार मिला तो अपनी सेना से यूनानी सेना के साथ युद्ध शुरु कर दिया। दोनों के बीच घोर युद्ध हुआ। सिकन्दर के साथ यूनानी सेना तथा कई हजार जाट सैनिक थे, जिनको अपने साथ सीथिया तथा सोग्डियाना से लाया था, जहां पर इन जाटों का राज्य था। पोरस की जाट सेना ने सिकन्दर की सेना के दांत खट्टे कर दिए।

पोरस की हार लिखने वालों का खण्डन करते हुए “एनेबेसिस् ऑफ अलेक्जेण्डर” पुस्तक का लेखक, पांचवें खण्ड के 18वें अध्याय में लिखता है कि “इस युद्ध में पूरी विजय किसी की नहीं हुई। सिकन्दर थककर विश्राम करने चला गया। उसने पोरस को बुलाने के लिए एक दूत भेजा। पोरस निर्भय होकर सिकन्दर के स्थान पर ही मिला और सम्मानपूर्वक संधि हो गई।” सिकन्दर अत्यन्त उच्चाकांक्षी था सही किन्तु इस साढे-छः फुट ऊँचे पोरस जैसा कर्मठ और शूरवीर न था। सिकन्दर उसकी इस विशेषता से परिचित था, उसी से प्रेरित होकर उसने भिम्बर व राजौरी (कश्मीर में) पोरस को देकर अपनी मैत्री स्थिर कर ली। पोरस का अपना राज्य तो स्वाधीन था ही। अतः पोरस की पराजय की घटना नितांत कल्पित और अत्युक्ति मात्र है[20]।

सिकन्दर चनाब नदी पार के छोटे पुरु राज्य में पहुंचा। यह बड़े पुरु का (पोरस का) रिश्तेदार था। इसके अतिरिक्त रावी के साथ एक लड़ाका जाति अगलासाई के नाम से प्रसिद्ध थी, इनको सिकन्दर ने जीत लिया। छोटे पुरु का राज्य भी सिकन्दर ने बड़े पुरु को दे दिया। रावी व व्यास के नीचे वाले क्षेत्र में कठ गोत्र के जाटों का अधिकार था। इनका यूनानी सेना से युद्ध हुआ। इन जाट वीरों ने यूनानी सेना को मुंहतोड़ जवाब दिया और आगे बढ़ने से रोक दिया। सिकन्दर ने पोरस से 5000 सैनिक मंगवाये। तब बड़ी कठिनाई के व्यास नदी तक पहुंचा। इससे आगे यूनानी सेना ने बढने से इन्कार कर दिया। इसका बड़ा कारण यह था - व्यास के आगे यौधेय गोत्र के जाटों का राज्य था। उनका शक्तिशाली यौधेय गणराज्य एक विशाल प्रदेश पर था। पूर्व में सहारनपुर से लेकर पश्चिम में बहावलपुर तक और उत्तर-पश्चिम में लुधियाना से लेकर दक्षिण-पूर्व में दिल्ली-आगरा तक उनका राज्य फैला हुआ था। ये लोग अत्यन्त वीर और युद्धप्रिय थे। इनकी वीरता और साधनों के विषय में सुनकर ही यूनानी सैनिकों की हिम्मत टूट गई और उन्होंने आगे बढ़ने से इन्कार कर दिया। ऐसी परिस्थिति में सिकन्दर को व्यास नदी से ही वापिस लौटना पड़ा। वापसी में सिकन्दर की सेना का मद्र, मालव, क्षुद्रक और शिव गोत्र के जाटों ने बड़ी वीरता से मुकाबला किया और सिकन्दर को घायल कर दिया। 323 ई० पू० सिकन्दर बिलोचिस्तान होता हुआ बैबीलोन पहुंचा, जहां पर 33 वर्ष की आयु में उसका देहान्त हो गया[21]

सिकन्दर की सेना का यूनान से चलकर भारतवर्ष पर आक्रमण और उसकी वापसी तक, जहां-जहां जाट वीरों ने उससे युद्ध तथा साथ दिया, का विस्तार से वर्णन अगले अध्याय में किया जाएगा।

जाट वीरों का इतिहास: दलीप सिंह अहलावत, पृष्ठान्त-193

सम्राट् पुरु (पोरस) के राजवंश का शासन 140 वर्ष तक रहा। मसूदी की लिखित पुस्तक ‘गोल्डन मीडोज’, का संकेत देकर, बी० एस० दहिया ने जाट्स दी एन्शन्ट रूलर्स पृ० 315 में लिखा है। धौलपुर जाट राजवंश भी पुरुवंशज था। राजा वीरभद्र पुरुवंशज थे। उनके पुत्र-पौत्रों से कई जाट गोत्र चले। (देखो वंशावली प्रथम अध्याय)। इस पुरुवंश के जाट पुरुवाल, पोरसवाल, फ़लसवाल पौडिया भी कहलाते हैं। पुरु-पोरव-पोरस जाट गोत्र एक ही है। पुरुगोत्र (वंश) के जाट आजकल उत्तरप्रदेश, हरयाणा, पंजाब तथा देहली में हैं परन्तु इनकी संख्या कम है। फलसवाल जाट गांव भदानी जिला रोहतक और पहाड़ीधीरज देहली में हैं।

पोरव वंश के शाखा गोत्र - 1. पंवार 2. जगदेव पंवार 3. लोहचब पंवार।

राजा पुरु-पोरस

राजा पोरस जाट जाति का था जिसका गोत्र पुरु-पौरव था। इसका राज्य जेहलम तथा चिनाब नदियों के बीच के क्षेत्र पर था। यह उस समय के पंजाब और सिन्ध नदी पार के सब राजाओं से अधिक शक्तिशाली था। सिकन्दर ने राजा पोरस को अपनी प्रभुता स्वीकार कराने हेतु संदेश भेजा जिसको पोरस ने बड़ी निडरता से अस्वीकार कर दिया और युद्ध के लिए तैयार

जाट वीरों का इतिहास: दलीप सिंह अहलावत, पृष्ठान्त-361

हो गया। सिकन्दर की सेना ने रात्रि में जेहलम नदी पार कर ली। पोरस की जाट वीर सेना ने उसका सामना किया। दोनों सेनाओं के बीच भयंकर युद्ध हुआ। दोनों ओर से जाट सैनिक बड़ी वीरता से लड़े। यह पिछले पृष्ठों पर लिखा गया है कि सिकन्दर के साथ यूनानी सैनिक तथा सीथिया व सोग्डियाना देश के दहिया आदि कई हजार जाट सैनिक आये थे।

पोरस की जाट सेना ने सिकन्दर की सेना के दांत खट्टे कर दिये। इस युद्ध में पूरी विजय किसी की नहीं हुई। सिकन्दर ने यह सोचकर कि पोरस हमको आगे बढ़ने में बड़ी रुकावट बन गया है, उसे अपने कैम्प में बुलाकर सन्धि कर ली। इस सन्धि के अनुसार सिकन्दर ने पोरस से मित्रता कर ली और उसे अपने जीते हुए भिम्बर व राजौरी (कश्मीर में) दे दिये। (अधिक जानकारी के लिए देखो तृतीय अध्याय, पुरु-पौरव प्रकरण)। जाट्स दी ऐनशन्ट रूलर्ज पृ 170 पर, बी० एस० दहिया ने लिखा है कि सम्राट् पोरस ने सम्राट् सिकन्दर से युद्ध किया और उससे हार नहीं मानी, अन्त में सिकन्दर ने इससे आदरणीय सन्धि की।

“लम्बा उज्जवल शरीर, योद्धा तथा शूरवीर, शत्रु पर तीव्र गति से भाला मारने वाले और युद्धक्षेत्र में भय पैदा करने वाले इस सम्राट् पुरु (पोरस) के 326 ई० पू० जेहलम के युद्ध में वीरता के अद्भुत कार्य, तांबे की प्लेटों पर नक्काशी करके तक्षशिला के मन्दिर की दीवारों पर लटकाए गए थे।” R.C. Majumdar Classical Accounts of India, P. 388; quoted SIH & C, P.69.)

छोटा पुरु तथा गलासाई जाति - सिकन्दर चनाब नदी पार करके छोटे पुरु के राज्य में प्रवेश कर गया। यह पुरु भी जाट राजा था जो कि बड़े पुरु का रिश्तेदार था। इसका राज्य चनाब और रावी नदियों के मध्य में था। सिकन्दर ने इसको जीत लिया और इसका राज्य भी बड़े पुरु को दे दिया। आगे बढ़ने पर उसका युद्ध एक लड़ाका अगलासाई* जाति जो कि रावी नदी के साथ थी, से हुआ। सिकन्दर ने उन पर भी विजय प्राप्त कर ली।

पोरस की जाति

पोरस की जाति संबंधी उल्लेख किसी भी ग्रंथ में नहीं मिलता. इतिहास में पोरस तथा एलेग्जेंडर का युद्ध भारत में एक घटना बनकर रह गया, जिसका उल्लेख इतिहास में एक झलक भर है. ऐसी बहुत सारी घटनाएं इतिहास में हो जाती हैं, परंतु वे इतिहास में लेखकों का अधिक ध्यान आकर्षित नहीं करती. पुरातन पोरस के वंशधारों तथा उसके समान वर्षों से संबंधित लोगों की खोज होनी चाहिए. इतिहास इस विषय में मौन है कि पोरस क्षत्रिय वर्ण में कौन जाति का था. पोरस के नाम के साथ पौरव उपाधि लगाने से यह तो स्पष्ट ही है कि वह पुरू वंशी था, किंतु जाति की गहराई में जाने के लिए ईस्वी पूर्व के इतिहास में पाई जाने वाली जातियों में उसके वंशजों का अन्वेषण किए जाने से जाट क्षत्रियों में आज भी पोरसवाल विद्यमान हैं, जिनको पोरस के नाम पर अपना पूर्वज होने के लिए आज भी अभिमान है. पौरव शब्द में 'व' हटाकर ग्रीक अस (os) जोड़ने से पोरोस तथा बदलकर पोरस बना. पोरस में 'वाल' प्रत्यय जोड़ने पर पोरसवाल अथवा परसवाल बन गया. 'वाल' या 'वाला' का अर्थ है प्रथम शब्द से संबंधित जैसे कर्णवाल, कर्ण से संबंधित है.

रोहतक में स्थित भदानी गांव आधा पोरसवाल जाटों का है. इस गांव के एक वंशधर दिल्ली के पश्चिम की ओर एक पहाड़ी पर बस गए. उनकी परंपरा में धीरजराव बड़े प्रसिद्ध पुरुष हुए. जब दिल्ली की आबादी उसकी चारदीवारी के बाहर चारों ओर बढ़ी तब जहां आज सदर बाजार है, वहां जाटों की आबादी की यह पहाड़ी- धीरज की पहाड़ी के नाम पर प्रसिद्ध हुई.

पोरस के भतीजे को भी ग्रीक लेखकों ने पोरोस/पोरस ही लिखा है. स्ट्रेबों लिखता है कि इंडिया के पोरोस/ पोरस नाम के दूसरे राजा ने रोमन सम्राट अगस्टस सीजर की कोर्ट में अपना राजदूत भेजा. अतएव ग्रीक लेखकों के अनुसार पोरोस न तो किसी व्यक्ति का नाम, न ही किसी राजवंश का नाम है. यह जाति/वंश का नाम है जो इंडिया के जाटों में पाया जाता है.

पारसियों के धर्मग्रन्थ अवेस्ता में इस जातिवंश को पोरु लिखा है. पोर, पौर तथा पुरु सभी शब्द एक ही हैं, अंतर स्थान तथा भाषा भेद के कारण है. स्थान तथा भाषा परिवर्तन के कारण शब्द का उच्चारण बदल जाता है जैसे वोट बंगाल में भोट, हिंदी में चक्रवर्ती बंगाल में चक्रबोर्ती जैसे हिंदी में पोरस तथा ग्रीक में पोरोस. परसवाल में है प, फ में बदल जाता है जैसे पत्थर से फत्थर. अतएव परसवाल से ग्रामीण भाषा में फरसवाल बन गया. भारतवर्ष में किसी भी जाति में जाटों को छोड़कर परसवाल नहीं पाए जाते, केवल जाट ही परसवाल है. इस वंश के बहुत सारे काम हैं जैसे कि बुलंदशहर उत्तर प्रदेश में लोहरका, जालंधर में शंकरगांव, गाजियाबाद में सुल्तानपुर, बिजनौर में कादीपुर आदि.

साभार - यह भाग जाट समाज पत्रिका आगरा, जून-2019, में प्रकाशित लेखक तेजपाल सिंह के पोरस पर लिखे गए लेख के पृ. 13 से लिया गया है.

Notes

- ↑ www.livius.org

- ↑ Buddha Prakash:Evolution of Heroic Tradition in Ancient Panjab, VIII. The Resistance to the Macedonian Invasion,p.73

- ↑ Jats the Ancient Rulers (A clan study)/Porus and the Mauryas, p.174

- ↑ History of the Jats/Chapter II,p. 31-32

- ↑ History of the Jats/Chapter IV ,p. 50

- ↑ Dr Mahendra Singh Arya, Dharmpal Singh Dudi, Kishan Singh Faujdar & Vijendra Singh Narwar: Ādhunik Jat Itihasa (The modern history of Jats), Agra 1998 (Page 290)

- ↑ History of Porus, Patiala, Dr Buddha Parkash.

- ↑ Buddha Prakash:Evolution of Heroic Tradition in Ancient Panjab, VIII. The Resistance to the Macedonian Invasion,p.73

- ↑ Buddha Prakash:Evolution of Heroic Tradition in Ancient Panjab, IX. The Contribution to the Maurya and Sunga Empires, p.91

- ↑ The Anabasis of Alexander/5a, Ch.8

- ↑ The Anabasis of Alexander/5a, Ch.14

- ↑ The Anabasis of Alexander/5a, Ch.15

- ↑ The Anabasis of Alexander/5a, Ch.16

- ↑ The Anabasis of Alexander/5a, Ch.17

- ↑ The Anabasis of Alexander/5a, Ch.18

- ↑ The Anabasis of Alexander/5a, Ch.19

- ↑ The Ancient Geography of India/Taki,pp.

- ↑ जाट वीरों का इतिहास: दलीप सिंह अहलावत, पृष्ठ.192-194

- ↑ Strabo, Geography bk, xv, Ch. 1, P 73

- ↑ क्षत्रिय जातियों का उत्थान, पतन एवं जाटों का उत्कर्ष पृ० 309 लेखक कविराज योगेन्द्रपाल शास्त्री।

- ↑ भारत का इतिहास पृ० 47, हरयाणा विद्यालय शिक्षा बोर्ड, भिवानी।

References

- Arrian, The Campaigns of Alexander, book 5.

- History of Porus, Patiala, Dr Buddha Parkash.

- Lendring, Jona. Alexander de Grote - De ondergang van het Perzische rijk (Alexander the Great. The demise of the Persian empire),Amsterdam:Athenaeum - Polak & Van Gennep, 2004.

- Holt, Frank L. Alexander the Great and the Mystery of the Elephant Medallions, California: University of California Press, 2003, 217pgs. ISBN 0-520-24483-4

External links

Back to The Ancient Jats